Lieutenant Colonel Mike Iron Man Sterling thought he was looking at a timid, middle-aged civilian nurse, a barrier between him and the medical care he demanded. He saw the graying hair and the soft voice, and he saw weakness. He didn’t see the woman who had once held a dying Marine’s artery closed with her bare fingers for 2 hours in the dusting heat of Sanin.

He didn’t see the legend whispered about in the barracks of the First Marine Division. He refused her help, barking for a real coreman. He had no idea that the woman standing before him didn’t just serve the core. She had saved it. And when she finally rolled up her sleeve, the ink on her skin would bring the entire hospital to a standstill.

The automatic doors of the Naval Medical Center San Diego, affectionately known as Balboa, slid open with a sharp hiss, admitting a gust of unseasonably warm November air, and a man who looked like he was carved from granite and regret. Lieutenant Colonel Mike Sterling did not walk. He marched, though the hitch in his left stride betrayed the agony radiating from his hip.

He was a man of the old breed, a marine’s marine with a jawline that could cut glass and eyes the color of a stormy Atlantic Ocean. Even in civilian clothes, a tight-fitting polo that strained against his biceps and tactical cargo pants, he radiated authority. He was the commanding officer of the third battalion, Fifth Marines, the legendary Darkhorse Battalion, and he was not accustomed to waiting.

He gripped the reception counter with knuckles that turned white. The young petty officer behind the desk, a hospitalman apprentice barely out of high school, looked up and swallowed hard. Sir, the young man squeaked. I need a consult. Orthopedics. Now, Sterling growled. His voice was a low rumble, like a tank idling in a garage.

My hip feels like someone replaced the joint with broken glass. Do do you have an appointment, Colonel? Sterling leaned in. Son, I have a battalion deploying in 3 weeks. I don’t have time for appointments. I have shrapnel shifting in my hip from Fallujah, and it’s deciding to migrate south today. Get me a doctor. Preferably one who knows the difference between a femur and a fibula.

The lobby was bustling. It was Friday afternoon, the witching hour for military hospitals, where training accidents, weekend warriors, and old veterans converged in a chaotic symphony of pain. I’ll I’ll see who is available, sir. Please take a seat. Sterling didn’t sit. He paced. Every step sent a jolt of electricity up his spine, but he refused to show it.

Pain was just weakness leaving the body. Or so the saying went. But this pain felt less like weakness leaving and more like a hot poker twisting in his marrow. 10 minutes passed, then 20. Sterling’s patience, never his strong suit, was fraying like an old rope. Finally, a side door opened, outstepped a woman.

She was short, perhaps 5’4, with a figure that had softened with age. Her scrubs were a generic faded seal blue, devoid of the sharp creases Sterling admired in his marines. Her hair was pulled back in a messy bun, strands of silver, fighting a losing battle against the dark brown. She wore comfortable, worn out clogs, and reading glasses perched precariously on the end of her nose.

She looked to Sterling’s discerning and prejudiced eye like a substitute teacher or a grandmother who baked cookies, not a warrior. Not someone capable of handling the damaged machinery of a marine commander. “Lieutenant Colonel Sterling,” she called out. Her voice was calm, almost melodic, cutting through the den of the waiting room.

Sterling stopped pacing and turned. He looked over her shoulder, expecting a doctor, or at least a chief petty officer. I’m Sterling. I’m nurse Sarah Jenkins, she said, offering a small, polite smile. I’ll be doing your intake and initial assessment before the surgeon sees you. If you’ll follow me to triage room 3. Sterling didn’t move.

He looked at her outstretched hand, then back at her face, his expression hardening. Nurse Jenkins, Sterling said, testing the name like it was a questionable piece of meat. Are you active duty? Sarah blinked, surprised by the question. I am a civilian nurse, Colonel. I’ve been with Balboa for 15 years now.

If you civilian, Sterling interrupted, the word tasting like ash in his mouth. He let out a sharp, derisive exhale. I specifically requested a military provider. I need someone who understands combat trauma, not someone who’s used to putting band-aids on dependent scraped knees. The lobby went quiet. A few heads turned. Sarah lowered her hand slowly.

Her expression didn’t change, but her eyes, hazel and sharp, seemed to assess him with a new intensity. Colonel, your status indicates urgent pain. The orthopedic surgeon, Commander Halloway, is in surgery. I am the senior triage nurse. I am fully qualified to assess your injury and administer pain management protocols until he is out.

Pain management? Sterling scoffed,stepping closer, towering over her. I don’t need pills, and I don’t need a civilian guessing game. I have metal fragments lodged in my iliac crest. Do you even know what an IED blast does to bone density over 20 years? I am quite familiar with blast injuries, Colonel Sarah said softly.

I doubt that, Sterling snapped. Unless you picked that up watching Gray’s anatomy. He turned back to the terrified young corman at the desk. Get me a corman, a chief, someone who has actually worn the uniform. I’m not letting a civilian touch me. Sarah stood her ground. She didn’t flinch. She didn’t retreat. She simply clasped her hands in front of her.

Colonel Sterling, refusing care is your right, but I am the only one available to help you right now. You are sweating, your pupils are dilated, and you are favoring your left side to the point of causing secondary strain on your lumbar spine. You are in agony. Let me help you.

I said no, Sterling barked, his voice echoing off the lenolium floors. I’ll wait for Halloway. and while I wait, get me someone with a rank on their collar, not a union card in their pocket.” He turned his back on her and limped aggressively toward a row of chairs, sitting down with a grimace that laid bare his suffering. Sarah watched him for a long moment.

A younger nurse might have run off to cry in the breakroom. A prouder nurse might have argued back. Sarah did neither. She simply adjusted her glasses, picked up her clipboard, and walked over to him. I’m not going anywhere, Colonel,” she said, her voice dropping to a register that was steel wrapped in velvet, because in about 10 minutes that hip is going to lock up completely, and you’re going to need help just to stand up.

I’ll be right here.” Sterling glared at her, his eyes narrowing. “You’re dismissed, nurse. This is a hospital, Colonel, not a parade deck,” she replied smoothly. and until you check out, you’re my patient.” She took a seat directly across from him, crossed her legs, and waited. The battle lines were drawn.

The standoff in the waiting room of the Naval Medical Center lasted for 45 minutes. To the casual observer, it was just a man sitting in a chair and a nurse sitting opposite him, reviewing charts, but the tension in the air was thick enough to choke on. Mike Sterling was deteriorating. He knew it, and he hated that she knew it, too.

The adrenaline that had carried him through the front doors was fading, replaced by a throbbing, white hot nausea. The shrapnel, a souvenir from a roadside bomb in Ramadi back in 06, had likely shifted millimeters, but inside the tight architecture of the hip joint, millimeters felt like miles. He tried to shift his weight, and a gasp escaped his lips before he could suppress it.

Sarah didn’t look up from her clipboard. Seven out of 10? She asked casually. Mind your business? Sterling gritted out, sweat beading on his forehead. Looks like an eight. Maybe a nine, she continued, turning a page. You’re going rigid. Muscle spasms are setting in. If we don’t get you a muscle relaxant and an anti-inflammatory soon, we’re going to have to cut your pants off because you won’t be able to stand to take them off.

I have survived worse than a stiff leg, Sterling snarled. I took a round through the shoulder in Girere and walked three clicks to the evac point. I think I can handle a chair in San Diego. Gamir, Sarah repeated, the word rolling off her tongue with a strange familiarity. She finally looked up. 2008, that was a bad summer.

The heat alone was killing people. Sterling paused, his eyes locking onto hers. You read my file that quickly? I didn’t read your file, Colonel. I know the history. History Channel fan? He mocked, though his voice was weaker now. Something like that. She stood up. Colonel, please put aside the ego. You are the commander of the dark horse.

Your men need you functional right now. You are a liability to yourself. Let me take you back. Get an IV started and prep you for halloway. He’s scrubbing out of a knee replacement now. He’ll be here in 20 minutes. Sterling looked at the clock. The pain was becoming blinding. His vision was blurring at the edges.

He hated civilians. He found them soft, uncommitted, lacking the discipline that defined his existence. But he was a pragmatist. He couldn’t command a battalion from a hospital floor if he passed out. Fine, he spat. But you do the basics. You stick the vein, you hang the bag. If you miss the vein once, you’re done. I get a Corman.

Deal. Sarah’s face remained impassive. I won’t miss. She gestured for the orderly to bring a wheelchair. I walk, Sterling commanded, gripping the armrests. Colonel, I said I walk. He surged upward, using pure willpower to force his legs to straighten. He made it two steps before his left leg buckled.

He didn’t hit the floor. Before the orderly could even react, Sarah had moved with a speed that belied her appearance. She stepped into his falling weight, bracing her shoulderunder his good arm, locking her stance wide. She caught a 220lb marine dead weight without a grunt. “I’ve got you,” she whispered, her voice right at his ear.

It wasn’t the voice of a civilian nurse. It was the command voice of someone who had hauled bodies before. “Pivot on the right. Lean on me. Do not fight me, Sterling.” He was too shocked and too much in pain to argue. He leaned on her and she guided him into the wheelchair. The orderly shoved forward as he slumped into the seat, breathing heavily.

He looked up at her. She wasn’t even out of breath. She smoothed her scrub top, her face returning to that benign grandmotherly mask. Triage three, she said to the orderly stat. In the exam room, the atmosphere was clinical and cold. Sarah moved efficiently, snapping on gloves. She prepped his arm for an IV.

Sterling watched her like a hawk. You have steady hands, he admitted grudgingly. It helps when people stop yelling at me, she replied dryly. She swabbed the inside of his elbow. Big breath. She slid the needle in. Perfect stick. Flash of blood taped down. Done in 10 seconds. Competent, Sterling muttered. For a civilian.

Sarah hooked up the saline bag. She turned to the computer terminal to log the vitals. You hold a lot of anger, Colonel. It elevates your blood pressure. Not good for healing. It keeps me alive, he counted. It keeps my men alive. You wouldn’t understand. You clock out at 5:00 p.m. and go home to what? cats, a garden. Sarah stopped typing.

She didn’t turn around immediately. The room went silent, save for the hum of the air conditioning. I don’t have cats, she said quietly. And I don’t really have a home to go to anymore. My husband passed 5 years ago. Sorry, Sterling said, the automatic reflex of politeness kicking in. Civilian life has its own tragedies, I suppose.

Sarah turned then, and for the first time, Sterling saw a flash of fire in her eyes. It was gone as quickly as it appeared, but it unsettled him. “You think the uniform is the only thing that makes a soldier, Colonel?” she asked. “I think the uniform represents a sacrifice you can’t comprehend,” he said, doubling down.

“You treat the wounds, sure, but you don’t know how we got them. You don’t know the sound of the snap hiss of a bullet or the smell of burning diesel and blood. You fix us up and send us back. You’re a mechanic. We are the race cars. A mechanic? She repeated. A small sad smile played on her lips. Is that what you think I am? Prove me wrong, Sterling challenged, the pain meds starting to take the edge off, making him bolder.

Tell me the closest you’ve ever been to a kill zone. Watching it on CNN. Sarah walked over to the sink to wash her hands. She dried them slowly with a paper towel. The air in the room seemed to grow heavier, charged with an static electricity that made the hair on Sterling’s arms stand up. She turned to him, her face completely void of the polite customer service expression she had worn earlier.

You asked for a corman, Colonel, she said. You asked for someone who knows the difference between a femur and a fibula under fire. She reached for the collar of her scrub top. For a second, Sterling thought she was undressing, and he opened his mouth to object, but she didn’t take the top off. She grabbed the left sleeve of her undershirt, a long-sleeved white thermal she wore under the scrubs, and pushed it up.

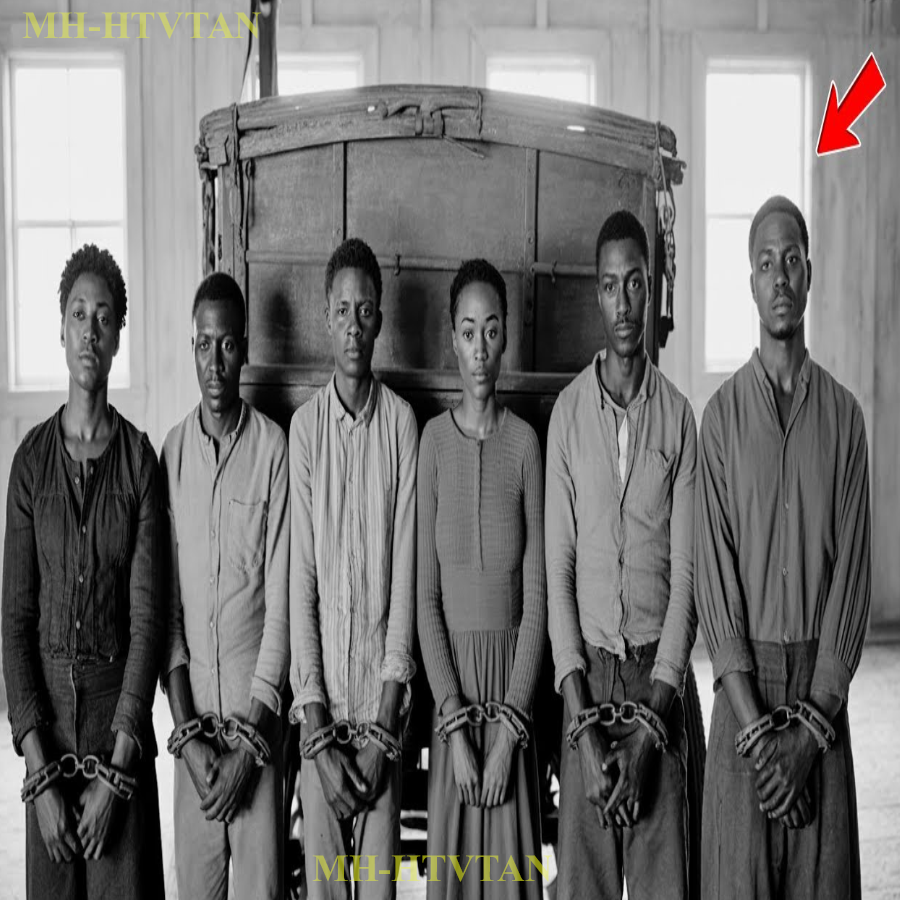

She rolled the fabric past her wrist, past the elbow. Sterling’s eyes widened. There, on the inside of her forearm, covering the pale skin from wrist to elbow, was a tattoo. But it wasn’t a butterfly or a flower. It was a chaotic, beautiful, terrifying mural of black and gray ink. In the center was the eagle, globe, and anchor, the sacred emblem of the Marine Corps.

But superimposed over it was the kaducius of the medical corps. And woven through the anchor chain were the distinct jagged lines of a map. Sterling knew maps. He knew that map. It was the street grid of Fallujah, the Jolan district. And below it, in bold Gothic script were the words, “So others may live.

” But what made Sterling’s breath catch in his throat, wasn’t the map. It was the small, distinct emblem inked right near the ditch of her elbow. a skull with a spade, the dark horse 3-fifths unit crest, and next to it a date, November 2004. Sterling stared. The year of the phantom fury, the bloodiest battle of the Iraq War.

You, Sterling stammered, his brain struggling to reconcile the middle-aged woman with the ink on her arm. You were attached to three fifths in 04. Sarah didn’t answer immediately. She rolled the sleeve up one inch further. There was a scar there, a jagged, ugly pucker of flesh that looked like it had been scooped out by a melon baller. “I wasn’t just attached,” Colonel Sarah said, her voice dropping to a whisper that carried the weight of a thousand graves.

“I was the lead surgical nurse for Bravo Surgical Company, deployed to the Hellhouse. We didn’t just fix you. We scraped you off the pavement.” Shetook a step closer to him, pointing a finger at his chest. And when your sergeant major, Gunny Miller back then, came in with his legs blown off at the knees, I didn’t wait for a doctor. I toted him with my own bootlaces because we ran out of cats.

So don’t you dare sit there and tell me I don’t know the smell of diesel and blood. I still wash it out of my hair every night. Sterling sat frozen. the IV drip, the only sound in the room. The twist was not just that she had served. It was that she had served in the very hell he had built his reputation on. “Miller,” Sterling whispered.

“You saved Gunny Miller.” “He died,” Sarah said flatly. “He died holding my hand, asking me to tell his wife he loved her. I was the last thing he saw. Not a marine. Me, a civilian in scrubs. The silence that followed was deafening. The silence in the examination room was heavier than the Kevlar vests Sterling used to wear.

The hum of the computer fan seemed to disappear, swallowed by the vacuum of the revelation. Sterling stared at the ink on Sarah’s arm, the map of the Jolan district, the kill zone where the third battalion, fifth marines, had bled for every inch of dust. He looked up from the tattoo to her face. The lines around her eyes, which he had dismissed as signs of a tired, middle-aged housewife, now looked like something else entirely.

They were etchings of sorrow. They were the marks of a witness. “You’re the angel,” Sterling whispered, the realization hitting him like a physical blow. “The angel of Jolan.” It was a myth he had heard when he was a young captain. The grunt spoke of a Navy nurse at the forward resuscitative surgical system, FRSS, a mobile trauma unit that moved with the front lines who refused to wear a flack jacket while operating because it restricted her movement.

They said she had blood up to her elbows for 3 weeks straight. They said she hummed laabis to Marines as they bled out when the morphine ran dry. Sarah pulled her sleeve down slowly, covering the map, covering the skull, covering the history. I hate that name, she said softly. There are no angels in war, Colonel. Only ghosts and survivors.

I thought you were a myth, Sterling said, his voice raspy. We heard the FRSS took a direct hit. Mortars. They said the medical team was wiped out. Most were, Sarah said, turning back to the computer, though her hands were trembling slightly. It was November 12th. We were set up in an abandoned schoolhouse.

They walked the mortars in from the north. The first one took out the generator. The second one hit the triage tent. I was in the back, scrubbing in on a chest wound. She paused, her eyes unfocused, staring through the sterile white wall of the San Diego hospital and seeing a smoky blood red tent in Iraq. I spent the next 6 hours doing triage by flashlight, she continued. We didn’t have enough hands.

I had to choose, Colonel. Black tag or red tag? Who gets the plasma and who gets a hand to hold while they die? Gunny Miller. He was a red tag that turned black. I tried. God, I tried. Sterling felt a wave of shame, so intense it nearly eclipsed the pain in his hip. He had just berated this woman. He had called her a soft civilian.

He had mocked her for not knowing the smell of blood. I got out in 05, Sarah said, answering the question he hadn’t asked yet. I couldn’t wear the uniform anymore. Every time I put it on, I smelled burning flesh. I came here to Balboa because I couldn’t leave the Marines completely. I just I needed to treat them without the rank, without the politics.

I just wanted to be Sarah, just a nurse,” she turned to him, her expression hardening again. “So yes, Colonel, I am a civilian now, but do not mistake my lack of rank for a lack of capability. I have sewn more marines back together than you have commanded.” Sterling swallowed hard. The pain in his hip was now a dull, thumping roar, but his ego had been shattered.

He tried to sit up straighter, forcing a level of respect into his posture that he usually reserved for generals. “I apologize,” Sterling said. “The words felt foreign, but necessary. I was out of line. I assumed. You assumed what you saw,” Sarah interrupted gently. “That’s what Marines are trained to do. Assess threats.

I’m not a threat, Colonel. I’m your lifeline. She reached out and adjusted the flow on his IV. Now tell me about the pain. The real pain, not the I can take it version. The truth. Sterling looked at her. Really? Looked at her and nodded. It’s not just the joint. It feels hot, like someone poured boiling water into the marrow.

And there’s a pulsing behind the hipbone, deep in the gut. Sarah’s eyes narrowed instantly. The grandmotherly softness vanished, replaced by the sharp, predatory focus of a combat clinician. “Pulsing?” she repeated. “Is it rhythmic? Does it match your heartbeat?” “Yeah,” Sterling grunted, wiping sweat from his upper lip.

“It’s getting louder.” Sarah didn’t speak. She immediately moved to his side, placingher hand not on his hip, but on his lower abdomen. just above the groin. She pressed down firmly. Sterling cried out a guttural sound that he couldn’t suppress. Rigid, Sarah muttered to herself. She moved her hand lower, checking the pulse in his left foot.

She frowned. She checked the right foot. Then the left again. What? Sterling asked, seeing the change in her demeanor. What is it? Your pedal pulse is weak on the left, Sarah said, her voice clipped and professional. And your abdomen is guarding. Colonel, when was your last X-ray? 6 months ago. Routine checkup.

And the shrapnel? Where exactly was it sitting? Lodged in the illium. Doctors said it was encapsulated. Safe. Encapsulated shrapnel doesn’t pulse, Sarah said grimly. She ripped the Velcro blood pressure cuff off the wall mount and wrapped it around his arm manually, trusting her ears over the machine. She pumped the bulb, listening intently with her stethoscope. She watched the gauge.

Then she released the valve. BP is dropping, she announced. 90 over 60. You were 130 over 85 when you walked in. I feel tired, Sterling admitted, his head lolling back against the headrest. The room was starting to swim. Just need a minute. Sarah didn’t give him a minute. She spun around and hit the red staff assist button on the wall.

The alarm blared into the hallway. A sharp rhythmic screech that signaled an emergency. Nurse Jenkins. The young coreman from the front desk poked his head in, looking terrified by the alarm. Get a gurnie in here now. Sarah barked. It wasn’t a request. It was an order delivered with the volume and authority of a drill instructor and page vascular.

Tell them we have a suspected iliac artery rupture code three. Vascular? The corman stammered. But he’s here for ortho. Did I stutter? Petty officer. Sarah turned on him, her eyes blazing. Move. The corman scrambled. Sterling looked at her, his vision tunneling. Rupture, he mumbled. That sounds bad. The shrapnel moved,” Sarah said, leaning over him, her face close to his.

“It didn’t just migrate, Mike. It sliced something. You’re bleeding internally. We have to move.” It was the first time she had used his first name. It was the last thing he heard before the darkness took him. The world came back in flashes of chaotic noise and blinding light. Lieutenant Colonel Sterling was moving.

He was staring up at the acoustic ceiling tiles racing by. Someone was shouting, “Bep is tanking. 70 over 40. We’re losing the radial pulse. Fluids wide open. Squeeze the bags. Where the hell is the surgeon?” Sterling tried to turn his head, but his body felt like it was made of lead. He recognized the voice, shouting orders. It was Sarah.

They burst through a set of double doors into a trauma bay. The air was colder here. He was lifted. rough hands grabbing the sheet under him and transferred onto a hard trauma table. Trauma team to bay one, the PA system announced overhead. A young resident in a white coat rushed over looking at the monitors.

Oh, what do we have? I thought this was a hip consult. Retroparitinal bleed. Sarah’s voice cut through the noise. She was at the head of the bed managing the airway. Patient is posttop combat injury 20 years shrapnel migration he’s hypoalmic he needs blood not saline on eggg two units stat the resident hesitated looking at Sarah nurse we need a CT scan to confirm before we look at his belly Sarah shouted grabbing the resident’s hand and forcing it onto Sterling’s distended abdomen he’s rigid as a board if you send him to CT he dies in the

elevator This is a blowout. You need to clamp the aorta or get him to the O now. I I can’t open him up down here without an attending. The resident panicked. Dr. Halloway is still scrubbing out. Then get another attending, Sarah yelled. Sterling’s eyes fluttered. He felt cold. So incredibly cold.

It felt just like Girere, just like the ditch where he had bled for 3 hours waiting for the bird. This is it, he thought, taken out by a piece of metal 20 years late. In a waiting room in San Diego, he felt a hand grip his shoulder, a strong, warm hand. Mike, stay with me. Sarah was leaning over him. She wasn’t looking at the monitors.

She was looking right at him. Do not fade on me, Marine. You did not survive for Lua to die on my shift. Sarah, he gasped. The map. Forget the map. Focus on my voice. The monitor began to scream a steady, high-pitched tone. Vib, he’s coding. The resident yelled. Charging paddles. No. Sarah shoved the resident aside. He has no pressure. There’s nothing to pump.

It’s pea. Pulseless electrical activity from hypoalmia. Start compressions. Push. EPI. Sarah climbed onto a step stool instantly. She laced her fingers together, positioned herself over Sterling’s massive chest, and began to pump. 1 2 3 4. Come on, Mike. She grunted with the effort. Fight. Sterling floated. He was in a gray hallway.

At the end of the hall, he saw faces. He saw Gunny Miller. He saw the boys from three-fifths who hadn’t come home. Theywere waiting, smoking cigarettes, leaning against a Hesco barrier. Not yet, sir, Miller seemed to say. She’s not done with you. Thump, thump, thump. The force of Sarah’s compressions was brutal. She was cracking ribs.

She didn’t care. She was manually forcing his heart to circulate the little blood he had left. I need that blood. Sarah screamed at the nurses, running into the room. Squeeze it in. Pressure bag. Blood is hanging. Dr. Halloway is 2 minutes out. We don’t have 2 minutes. Sarah stopped compressions to check the pulse.

Nothing. She looked at the resident. Reboa, do we have a Reboa kit? The Rioa resuscitative endovvascular balloon occlusion of the aorta was a specialized device, a balloon threaded up the femoral artery to plug the aorta from the inside, stopping the bleeding below the chest and keeping the blood in the brain and heart. It was advanced.

It was risky. And it was usually done by a surgeon. I I’ve never done one, the resident admitted, his face pale. Sarah looked at the crash cart. She looked at the dying marine on the table. She made a choice that could end her career. A choice that could send her to prison if she failed. Open the kit, she ordered.

Nurse Jenkins, you can’t. I was F FRSS certified invascular access under fire, she snapped. I’ve done three of these in a ditch in Ramadi. Open the damn kit or get out of my way. The room went silent. The authority radiating off her was absolute. It was the angel of Jolan surfacing. The resident opened the kit. Sarah moved with terrifying speed.

She grabbed the ultrasound probe with her left hand, the access needle with her right. Compressions, hold, she barked. She scanned the right femoral artery. the good leg. Found it. She stuck the needle, flash of blood. She threaded the wire. Catheter. The resident handed it to her.

She slid the long slender tube up Sterling’s artery, guiding it blindly by feel and landmarks. Visualizing the anatomy in her head, she had to get the balloon high enough to block the blood flow to the hips, but not so high it stopped flow to the kidneys. deploying balloon,” she said calmly. She inflated the device inside Sterling’s aorta.

Everyone stared at the monitor. For 10 agonizing seconds, nothing happened. The line remained flat. Then a blip, then another. The blood pressure, which had been non-existent, suddenly registered. 6040ths, then 8050ths. By plugging the leak, she had forced the remaining blood back to his heart and brain.

Sinus rhythm. The resident breathed, looking at Sarah with awe. We have a pulse. Sarah didn’t celebrate. She slumped slightly, sweat dripping from her nose onto her mask. He’s stable. Get him to the O. Halloway can fix the tear now that he’s not bleeding out. The doors burst open. Doctor Halloway, a tall man with silver hair, rushed in, still tying his surgical mask.

He looked at the scene. the crash cart, the blood on the floor, the riboa catheter sticking out of Sterling’s leg, and Sarah standing there, chest heaving. “Status,” Halloway demanded. “Ruptured iliac from shrapnel migration,” the resident reported, his voice shaking. “He coded.” “Nurse Jenkins.” She placed a reboer. She brought him back. Holloway stopped.

He looked at the device. He looked at Sarah. He knew Sarah was a good nurse, but he had no idea she even knew what a riboa was, let alone how to place one in a coding patient. “You place this, Sarah?” Hoay asked. “He was dead, doctor.” Sarah said, her voice trembling now that the adrenaline was fading. “I didn’t have a choice.

” Halloway checked the monitor. “Placement looks perfect. You saved his life.” He turned to the team. “Let’s move or one is ready. We have a window. Let’s not waste it. As they wheeled Sterling out, Halloway paused and put a hand on Sarah’s shoulder. “We need to talk about this later,” he said seriously. “But good work, Lieutenant.

” He used her old rank. He knew. Sarah stood alone in the empty trauma bay. Her hands were covered in Sterling’s blood. She walked over to the sink, turned on the water, and rolled up her sleeves. The water ran red as she scrubbed. She looked at the tattoo on her arm. The map of Fallujah.

Not today, she whispered to the skull and spade. You don’t get him today. The intensive care unit at Baloa was a hushed cathedral of technology, a stark contrast to the chaotic noise of the trauma bay. Lieutenant Colonel Mike Sterling woke to the rhythmic whoosh click of a ventilator, though the tube had already been removed.

His throat felt like he’d swallowed broken glass, and his left side was a heavy, numb block of ice. He blinked, his eyes adjusting to the dim light. A figure was standing at the foot of his bed, reviewing a chart. It wasn’t Sarah. It was Dr. Halloway. “Welcome back to the land of the living, Colonel,” Halloway said, his voice low. He looked tired.

“You gave us quite a scare.” Sterling tried to speak, coughed, and accepted the ice chips Halloway offered. The hip, he rasped. Repaired, Halloway said. Weremoved the shrapnel. It had jagged edges. Looks like a piece of an old Soviet artillery shell. It sliced your common iliac artery. You bled out about 2 L into your retroparonial space.

Frankly, Mike, you should be dead. Sterling’s memory was a fragmented haze. He remembered the pain. He remembered the waiting room. He remembered Sarah, “The nurse,” Sterling whispered. “Sarah, she she was there.” Halloway’s expression tightened. He closed the chart and pulled a chair close to the bed. “That’s what we need to talk about.

Sarah Jenkins saved your life. There is no ambiguity there.” You coded. Your heart stopped. She performed a reboa procedure. She inserted a balloon into your aorta to stop the bleeding so we could get you to surgery. “So, she did her job,” Sterling said, confused by the doctor’s grim tone. “She did my job, Mike.

” Halloway corrected him. “The Reboa is a surgical procedure. It is not within the scope of practice for a civilian nurse at this facility. She isn’t credentialed for it. She didn’t wait for an attending. In the eyes of the hospital administration, she performed an unauthorized invasive surgery on a high-ranking officer. Sterling tried to sit up, but the pain forced him back. She saved me.

If she waited, I’d be in a box. I know that. You know that. But the hospital director, Steven Caldwell, sees it differently. He sees a massive liability lawsuit waiting to happen. If she had perforated your aorta, if you had died, the hospital would have been sued into oblivion for letting a nurse play surgeon. Sterling felt a surge of the old combat rage.

Where is she? She’s been placed on immediate administrative leave, Halloway sideighed, pending a review board hearing tomorrow morning. They’re going to fire her, Mike, and they might report her to the state board of nursing to have her license stripped. They’re calling it gross negligence and cowboy medicine. Cowboy medicine? Sterling growled.

She’s a combat veteran. She learned that in the dirt. Caldwell doesn’t care about what happened in Fallujah. He cares about protocol. And right now, Sarah is standing alone. Sterling looked at the IV lines running into his arm. He looked at the window where the San Diego sun was trying to break through the fog.

He remembered the tattoo so others may live. She had lived her creed and now they were crucifying her for it. When is this hearing? Sterling asked. Tomorrow at 090 in the administration wing. But you are not cleared to move, Colonel. You are barely 12 hours posttop. Sterling looked at Halloway with eyes that were cold and hard as steel.

Doctor, you patched the tire. Now get me the hell out of the garage. I’m going to that hearing. Mike, you can’t walk. Then find me a wheelchair, Sterling commanded. And get me my uniform. If they want to put a marine on trial for saving a marine, they’re going to have to look me in the eye when they do it.

The conference room on the top floor of the Naval Medical Center was sterile, air conditioned, and smelled of lemon polish and bureaucracy. A long mahogany table dominated the room. At the head sat Director Steven Caldwell, a man in a pristine gray suit who had never seen a day of combat in his life. He was flanked by the hospital’s chief legal counsel and the director of nursing.

Sarah Jenkins sat at the other end of the table. She wasn’t wearing scrubs today. She wore a simple navy blue blazer and slacks. Her hands were folded on the table, still and composed. She looked small against the backdrop of the institution she had served for 15 years. Miss Jenkins, Caldwell began, adjusting his glasses.

We have reviewed the incident report. The facts are not in dispute. You utilized a Reboa device on a patient without a physician present. You bypassed hospital protocol. You ignored the chain of command. And you performed a procedure for which you are not licensed in the state of California. The patient was in pea arrest, Sarah said, her voice steady but quiet.

He had exanguinated. Compressions were ineffective because the tank was empty. If I hadn’t oluded the aorta, he would have suffered irreversible brain death within 3 minutes. Dr. Halloway was still 2 minutes out. That is speculation, the legal council interjected. The resident, Dr. Evans, was present. You overruled him. Dr.

Evans froze, Sarah replied. He admitted he didn’t know how to use the device. I did. Where did you receive this training? Caldwell asked, his tone skeptical. Because I don’t see it in your file here at Balboa. I learned it in the Alanbar province, Iraq. 2004, Sarah said, under the supervision of Navy commander Dr. Aerys.

We didn’t have the fancy kit back then. We used Foley catheters and guesswork. But it worked, Caldwell sighed, taking off his glasses. Miss Jenkins, we respect your past service. But this is a civilian hospital in San Diego, not a triage tent in a war zone. We have rules. Those rules exist to protect patients. You can’t just improvise.

This is reckless endangerment. We have nochoice but to terminate your employment effectively immediately and refer this case to the board. Sarah looked down at her hands. She didn’t cry. She didn’t beg. She knew the rules. She knew she had broken them. But she also knew Sterling was alive. That had to be enough. I understand, she whispered.

Is there anything else you wish to say? Caldwell asked, reaching for the termination paperwork. The sound of an electric motor cut through the silence. The double doors at the back of the room swung open. Lieutenant Colonel Mike Sterling did not walk in. He rolled in. He was seated in a highbacked power wheelchair, his left leg elevated and wrapped in heavy compression bandages.

But from the waist up he was pure military perfection. Someone, likely a terrified corporal, had gone to his house and retrieved his service alphas. The olive green tunic was pressed sharp enough to cut paper. The ribbons on his chest were a colorful brick of history. The silver star, the bronze star with V, the purple heart with two stars.

He looked pale, ghostly even, but his eyes were burning. Behind him stood Dr. Halloway looking like a guilty accomplice. “Conel Sterling,” Caldwell stammered, standing up. “You You shouldn’t be here. You’re in critical condition.” “I’m in a chair,” Caldwell. “My ears work fine,” Sterling rumbled. He maneuvered the chair until he was right next to Sarah.

“He didn’t look at the director. He looked at her.” He gave her a subtle nod. Sarah looked at him, her eyes widening. “Mike, what are you doing?” “Ring the favor,” he muttered. Then he turned the chair to face the board. “You’re firing her?” Sterling asked, his voice deceptively calm. “Conel, this is an internal personnel matter,” the legal council said.

“It’s inappropriate for you to inappropriate.” Sterling laughed. A harsh barking sound. Inappropriate is dying in your lobby because your appointment system is backed up for 6 weeks. Inappropriate is a 20-year-old resident freezing up while a battalion commander bleeds out on his table. Miss Jenkins violated the law, Caldwell insisted, though he looked nervous.

She performed surgery. She performed a miracle. Sterling slammed his fist on the armrest of his chair. Do you know who this woman is? She is a staff nurse, Caldwell said. She is Lieutenant Sarah Jenkins, Navy Nurse Corps, retired, Sterling corrected him. She is the recipient of the Navy Commenation Medal with Valor.

She served with the Bravo Surgical Company in Fallujah during Operation Phantom Fury. The Marines called her the Angel of Jolan. The room went silent. The director of nursing looked up, surprised. That information wasn’t in her HR file. Sterling reached into his pocket. It was a struggle, and he grimaced in pain, but he pulled out a small folded piece of paper.

It was the print out of his vitals from the trauma bay. I had Dr. Halloway pull the logs, Sterling said, sliding the paper across the mahogany table toward Caldwell. Look at the time stamp. 1402, heart rate zero. BP0. Technically, gentlemen, I was dead. I was a corpse on your table. He pointed a finger at the paper.

1403, blood pressure 80 over 50, heart rate 110. That is the exact minute she placed the reba. She didn’t endanger a patient. She resurrected one. That doesn’t change the liability, Colonel Caldwell argued, though his voice was losing its steam. If we allow nurses to do this liability, Sterling cut him off.

You want to talk about liability? Fine. If you fire this woman, I will personally hold a press conference in the hospital lobby. I will tell every news outlet in America that the Naval Medical Center San Diego fired a war hero for saving the life of a decorated Marine commander because she didn’t fill out the right paperwork.

Sterling leaned forward, his voice dropping to a dangerous whisper. I command 3,000 Marines, Mr. Caldwell. They are very loyal and they have very loud voices on social media. Do you really want to be the man who fired the nurse who saved the dark horse commander? Caldwell pald. The legal council whispered something frantically in his ear.

The optics were a nightmare, a PR disaster of nuclear proportions. Sarah reached out and touched Sterling’s arm. Mike, stop. You don’t have to threaten them. I’m not threatening them, Sarah,” Sterling said softly. “I’m educating them.” He turned back to Caldwell. “Here is the New Deal. The investigation concludes that nurse Jenkins acted under the emergency directive of preservation of life in a mass casualty style event, which given the incompetence of your triage that day, it basically was.

You will reinstate her. You will place a commendation in her file and you will ensure she is credentialed to assist in trauma training for your residents so they don’t freeze next time. Caldwell looked at the legal council. The lawyer nodded slowly. It was the only way out. We we can structure it as a retroactively authorized emergency procedure, the lawyer said, typing frantically on his tablet. Under thegood Samaritan precedences.

Caldwell let out a long breath. He looked at Sarah, really seeing her for the first time. We will suspend the termination, pending a competency review, but she keeps her job. Sterling didn’t smile. He just nodded. Good choice. He turned his chair towards Sarah. Now, nurse Jenkins, I believe I am awol from my hospital bed, and I think my hip is starting to scream at me. Sarah stood up.

Tears were finally streaming down her face, but she was smiling. She walked behind his wheelchair and took the handles. “Let’s get you back, Colonel,” she said as she wheeled him out of the boardroom. Sterling looked straight ahead, his back rigid. But as the doors closed behind them, he reached up and patted her hand resting on the handle.

“You don’t leave a man behind,” he said. “And I don’t leave my medic.” 4 months later, the morning fog rolled off the coastal hills of Camp Pendleton, revealing the sprawling concrete expanse of the fifth Marines parade deck. The air was filled with the sharp staccato rhythm of drums and the bark of orders. It was a change of command ceremony, the sacred transfer of authority from one commander to the next.

Lieutenant Colonel Mike Sterling stood at the podium. He was in his dress blues, the high collar stiff against his neck, the metals on his chest gleaming in the California sun. He stood without a cane, though a slight, almost imperceptible shift in his stance betrayed the metal and screws now holding his hip together.

He looked out at the sea of faces, 3,000 marines and sailors of the Darkhorse Battalion, standing at rigid attention. In the VIP stands, amidst generals and politicians, sat a woman in a simple floral dress. Sarah Jenkins looked out of place among the uniforms, clutching her purse nervously.

Sterling cleared his throat, the sound amplified across the parade deck. He had already given the standard speech, thanking the core, thanking his family, promising victory. But he wasn’t done. Marines, Sterling’s voice boomed. We are taught that the uniform makes us brothers. We are taught that the eagle, globe, and anchor is earned through pain and dirt at boot camp.

We are taught that we are a breed apart. He paused, his eyes scanning the crowd until they locked onto Sarah in the stands. But 4 months ago, I was reminded that the warrior spirit does not always wear a camouflage uniform. Sometimes it wears blue scrubs. Sometimes it looks like a civilian that you might walk past in a hallway without a second glance.

A murmur went through the crowd. This was off script. I am standing here today, Sterling continued, his voice thick with emotion, because a woman refused to let me die. She disobeyed orders. She risked her career, and she put her own livelihood on the line to save a broken down old Marine who was too stubborn to admit he needed help.

He stepped back from the microphone and gestured towards the stands. Sarah Jenkins, front and center. Sarah froze. The generals around her turned to look. A young captain gestured for her to stand. Trembling, she stood up. “Escort her,” Sterling commanded. The sergeant major of the battalion, the highest ranking enlisted man, marched into the stands, offered Sarah his arm, and walked her down the stairs onto the sacred asphalt of the parade deck.

They walked until she stood right in front of the podium, dwarfed by the formation of marines behind her. Sterling limped down the steps of the podium to meet her on the ground level. He wasn’t looking at her like a patient looks at a nurse. He was looking at her like a soldier looks at a savior.

You told me once that you were just a mechanic, Sterling said, his voice low enough that only she and the front row could hear, and that you had to wash the war out of your hair every night. He reached into his pocket and pulled out a small velvet box. You never got to wear the combat action ribbon you earned in Jolan Park, Sterling said.

The paperwork was lost. The unit moved on. You were a ghost. He opened the box. Inside was a gold pin, not a standard medal, but a custommade emblem. It was the skull and spade of the dark horse, intertwined with the medical kaducius. I had the boys in the metal shop make this. Sterling smiled. A genuine warm smile that reached his eyes.

You are not a civilian, Sarah. You are Darkhorse. You are one of us. You always have been. He pinned the emblem onto the lapel of her dress. Then, Lieutenant Colonel Sterling, the Iron Man, the commander who had refused her help, took a step back. He snapped his heels together. He drew himself up to his full height, and he rendered a slow, crisp, perfect hand salute. It wasn’t a courtesy salute.

It was a salute of respect. “Battalion!” the sergeant major bellowed behind them. “Present, arms!” 3,000 Marines moved as one. 3,000 hands snapped to visors. The sound was like a thunderclap. Sarah stood there, the tears finally spilling over, washing away the years of silence, the years of hiding herservice, the years of being just a nurse.

She wasn’t hiding anymore. She looked at the tattoo on her arm, hidden beneath her sleeve, and she knew she didn’t need to show it to prove anything. They knew. Sterling held the salute for a long beat, his eyes locking with hers. “Welcome home, Lieutenant,” he whispered. Sarah straightened her back, wiped her eyes, and for the first time in 20 years, she felt the weight of the war lift off her shoulders. She smiled.

“Thank you, Colonel.” What an incredible journey. From a stubborn Marine commander refusing help in a waiting room to a battalionwide salute on the parade deck. It just goes to show that true heroism isn’t about the uniform you wear today, but the spirit you carry inside you always. Sarah Jenkins proved that a warrior’s heart beats just as strong in scrubs as it does in body armor.