AFTER MY HUSBAND DIED, HIS MOTHER SAID: “I’M TAKING THE HOUSE, THE LAW FIRM, ALL OF IT EXCEPT THE DAUGHTER.” MY ATTORNEY BEGGED ME TO FIGHT. I SAID: “LET THEM HAVE EVERYTHING.” EVERYONE THOUGHT I WAS CRAZY. AT THE FINAL HEARING, I SIGNED THE PAPERS. SHE WAS SMILING – UNTIL HER LAWYER. TURNED WHITE WHEN…

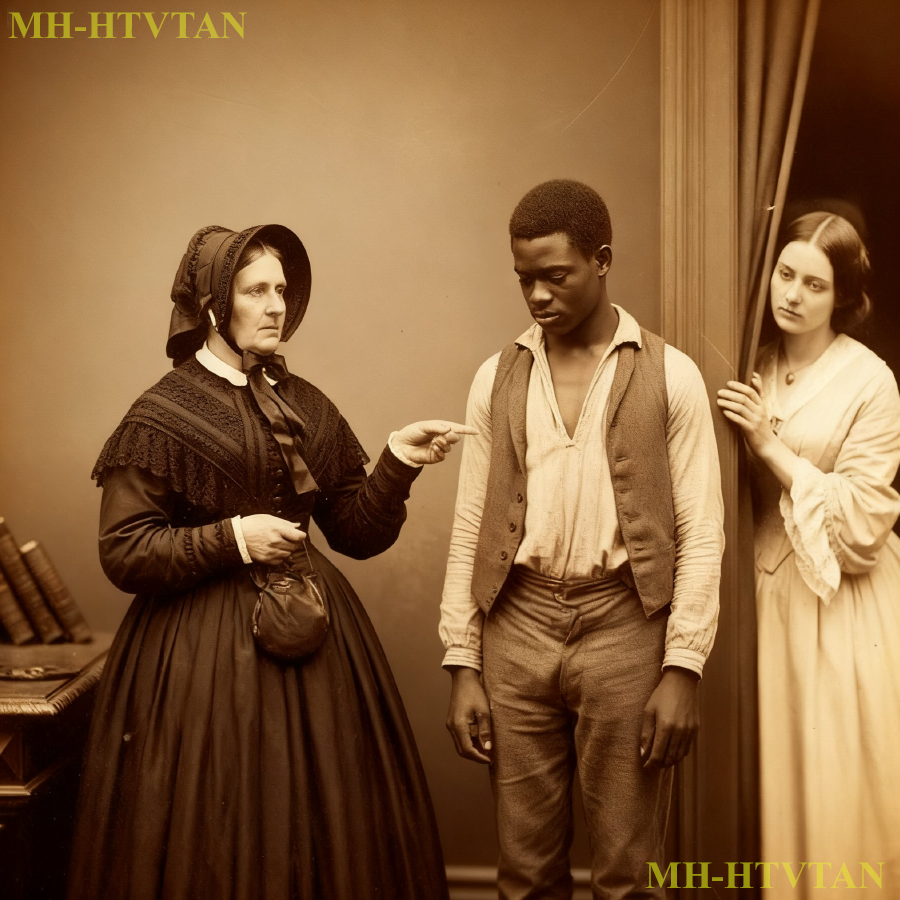

After my husband died, his mother wanted to take everything from me except the daughter. My lawyer begged me to fight. Carla Fredel stood in my kitchen 11 days after I buried my husband, pointed at the ceiling, the walls, the floor beneath her shoes, and told me she was taking all of it, the house, Joel’s law firm, every bank account, every asset down to the last dollar.

everything, Hana, except our four-year-old daughter, Tessa, because, and I will never forget how casually she said it, she didn’t sign up for someone else’s child. My name is Miriam Fredel. I’m 31 years old, and until recently, I lived in Covington, Kentucky, a small city that sits right across the Ohio River from Cincinnati.

The kind of place where people wave to each other from their driveways and somehow always know what you paid for your house. I married Joel Fredel when I was 24. He was a personal injury attorney who built his own firm from absolutely nothing. Well, from his mother’s $185,000 loan and about 6,000 hours of his own sweat.

He started in a tiny rented office above a flooring store on Madison Avenue. The kind of office where you could hear someone picking out laminate samples through the floor every time a client sat down for a consultation. Within five years, he’d moved to a real office suite, hired a small staff, and was billing over 600,000 a year.

Fredel and Associates. His name was on the door, and his mother never let anyone forget who paid for that door. Joel died on a Thursday evening, March 6th. Cardiac arrest. They found him at his desk at the office, his hand still on his coffee mug. He was 36 years old. I got the call while giving Tessa a bath. I drove to the office with wet sleeves rolled up to my elbows and soap still under my fingernails.

By the time I got there, the paramedics had already stopped trying. The funeral was the following Wednesday. Carla wore black Chanel sunglasses indoors, the kind that cover half your face so you can’t tell if the person is actually crying or just performing grief for an audience. Spencer, Joel’s younger brother, stood next to her looking like a kid waiting for the principal.

He was 29, had never held a job for more than 5 months, and lived in Carla’s guest house in Burlington, where his primary responsibilities were sleeping until noon and ordering things off the internet with her credit card. You need to understand something about Carla. She wasn’t some helpless old woman. She’d owned four dry cleaning stores across Northern Kentucky.

Built them up herself after her divorce from Joel’s father. She knew business. She knew numbers. Or at least she thought she did. The dry cleaning world runs on simple math. Clothes come in dirty. Clothes go out clean. Cash goes in the register. She applied that same logic to everything, including a law firm she’d never set foot inside professionally.

To Carla, Joel’s practice was just another store, except instead of pressing shirts, you pressed lawsuits, and instead of quarters in the machine, you had $600,000 a year rolling through the books. She also treated me from the very first Thanksgiving like I was a temporary inconvenience Joel would eventually outgrow.

I’d been a legal secretary when we met. Not glamorous, not rich, not from the right family. Carla once introduced me to her friends as Joel’s first wife while Joel and I were still very much married and standing right there. So, when she showed up in my kitchen that Monday morning, 11 days after the funeral, I shouldn’t have been surprised, but grief does something to your reflexes. It makes you slow.

You stand there absorbing punches you’d normally see coming from across the room. Carla walked in wearing a gray blazer. She’d actually dressed for this, like it was a business meeting. Spencer trailed behind her with a tape measure. An actual tape measure. While Carla stood at my kitchen island, explaining that she was reclaiming what her investment built, Spencer wandered into the guest bedroom and started measuring the closet.

I could hear the tape clicking and snapping from the kitchen. I remember thinking, “What does he even own that would fill a closet?” The man’s most valuable possession was a gaming chair. Carla laid out her case like she was giving a board presentation. The firm was built with her money, the house down payment.

She’d given us $30,000 7 years ago, and she had not stopped mentioning it since. In her mind, she was co-owner of everything Joel ever touched. And now that Joel was gone, she wanted her investment back with interest. The only thing she didn’t want was Tessa. She said it so matterof factly, like she was declining a side dish at a restaurant. No, thank you.

Not the child. Just the assets, please. I stood there holding a cup of coffee that had gone cold 20 minutes ago and said nothing. Not because I agreed, because my brain couldn’t process losing my husband and being robbed in the same month. 2 days later, a certified letter arrived. Axel Mendler, attorney at law.

Carla had filed a formal contest of Joel’s will and a creditor’s claim against his estate for her $185,000 loan. This wasn’t kitchen table talk anymore. This was a legal attack and she’d launched it before Joel’s flowers had even wilted on the grave.

Carla had gone from kitchen threats to courtroom filings in 48 hours, and I was still sleeping in a bed that smelled like my dead husband’s cologne, trying to figure out how to explain to a four-year-old why daddy wasn’t coming home. Axel Mendler was no amateur.

He filed the will contest on solid enough grounds, arguing that Carla’s $185,000 loan constituted an investment in the firm, giving her a claim to its value. He also filed a separate creditor’s claim for the loan itself. Two legal fronts at once. Carla was spending $350 an hour on this man, and she wanted results fast.

But Carla wasn’t content to wait for the legal system. She decided to start managing her new empire immediately. The week after filing, she drove to Joel’s office, Fredel and Associates, a second floor suite on Scott Boulevard, walked in like she owned the place, and started introducing herself to the staff. There were only four employees, two parallegals, one receptionist, and Gail Horvath, the bookkeeper, who’d been with Joel for 6 years.

Carla told them all she was assuming oversight of operations, and that changes were coming. She told Gail to print out the firm’s revenue reports for the last 3 years. Gail printed them. Carla looked at the top line. 620,000 in annual billings, nodded like she just confirmed what she already knew and left.

She never asked for the expense reports. She never asked about debts. She never opened a single folder that wasn’t labeled income. It’s like checking your bank balance, but only looking at deposits and deciding you’re a millionaire. Then she started calling Joel’s clients. One by one, she tracked down their numbers and called to introduce herself as the person who’d be overseeing the transition.

She had no legal authority to do this. She had no law license. She didn’t even know what half of Joel’s cases involved. But Carla believed that confidence was the same thing as competence. And she had confidence to spare. Most of Joel’s clients, understandably alarmed by a phone call from their dead lawyer’s mother, transferred to other firms within days.

Carla was systematically destroying the revenue stream of the very business she was fighting to own. It was like watching someone set fire to a house while arguing with the insurance company about how much the house was worth. Then Spencer happened. A week after Carla’s office visit, Spencer pulled up to my house in Carla’s Buick Enclave with two duffel bags, a playstation, and a large bag of barbecue chips.

He walked to the front door and announced that he was moving into the guest bedroom because, and I quote, “Mom said it’s basically ours now.” Anyway, he did not bring sheets, a pillow, or a single change of professional clothing. He brought a gaming console and snacks. I told him to leave. He refused. I called the Covington police. Two officers arrived, confirmed that the house was in Joel’s name, and I was the surviving spouse, and escorted Spencer back to the Buick.

He left the chips on my porch, I threw them away. That night, Carla called me. Her voice hit a pitch I didn’t know human vocal cords could produce. Somewhere between a smoke alarm and an opera singer warming up for a death scene, she told me I was heartless, cruel, and that Joel would be disgusted with me for throwing his brother onto the street.

I reminded her that Spencer lived in her guest house and had his own bedroom there. She hung up on me. Meanwhile, my own people were losing faith in me. My mom drove up from Lexington that weekend, sat at my kitchen table, the same table where Carla had laid out her hostile takeover plan and said, “Honey, you have got to fight this.

” My best friend Shannon called every night saying the same thing. Get a lawyer. Get a shark. Don’t let this woman steamroll you. So I hired LRA Schmidt. She came recommended by a colleague of Joles, a German American woman in her mid50s with silver streaked hair and the kind of calm, precise energy that made you feel like everything might actually be okay.

LRA had handled estate disputes for 20 years. She reviewed Carla’s filings in about 40 minutes and told me it was beatable. The loan had no partnership agreement, no formal terms, nothing in writing that gave Carla equity in the firm. The will was clean and properly executed. LRA said, “We fight, we win, and Carla goes home with nothing but a lesson in contract law.

” I told LRA I needed a few days to think. That night, after Tessa was asleep, I drove to Joel’s office. It was almost 9:00. The building was dark except for the exit signs glowing green in the stairwell. I unlocked Joel’s private office with the spare key I’d always kept on my keychain and sat down at his desk. It still smelled like him.

Coffee and that sandalwood after shave he’d used since college. I opened the bottom drawer, the deep one where he kept files he didn’t want anyone else touching. Behind a stack of old case folders, I found a sealed manila envelope. My name was written on the front in Joel’s handwriting. Not Miriam Fredel, just Miriam with a small heart drawn next to it like we were still passing notes in high school. I opened it.

I read what was inside. And I sat in that dark office for almost an hour without moving, without breathing hard, without crying. For the first time since March 6th, my mind was completely clear. The next morning, I called LRA. My voice was different. I could hear it myself. steady, calm, like something had clicked into place behind my eyes.

I said, “Laer, I’ve changed my mind. I don’t want to fight. I want to give Carla everything she’s asking for. Everything.” LRA didn’t say a word for about 10 seconds. And for a woman who bills by the hour, 10 seconds of silence is practically a medical event. I need to tell you what was in that envelope. Because this is where the story changes direction.

And if you don’t understand what Joel did in the last months of his life, nothing that comes next will make sense. Eight months before he died, Joel was diagnosed with a serious heart condition. He’d been having episodes, shortness of breath during routine things like climbing stairs, chest tightness that came and went, a strange fatigue that sleep didn’t fix.

He finally went to a cardiologist in Cincinnati, a specialist at one of the big hospital systems across the river. The diagnosis was bad. Not immediately fatal, but the kind of bad where your doctor uses phrases like progressive and long-term management while looking at you like they’re sorry they went to medical school.

Joel told me he did not tell his mother, his brother, or anyone else. You need to understand something about Joel. He was a personal injury lawyer. He spent his entire career looking at how people’s lives fell apart because someone didn’t plan. Someone cut corners. Someone assumed everything would be fine. He was not going to let that happen to his family.

So over those eight months, while he was still going to the office every day, still wearing his good suits, still telling his mother about his big cases at Sunday dinner, he was quietly, methodically arranging the pieces. The envelope contained three things. First, a letter handwritten dated five weeks before he died.

It wasn’t a financial document. It was a letter from my husband to me. He wrote about Tessa, how she’d started calling butterflies flutterbees, and he never wanted to correct her. He wrote about our kitchen, how the morning light came through the window, over the sink, and hit the counter at exactly the angle that made everything look golden.

He wrote about the day we met when I was 22 and working at the front desk of Bernstein and Kellogg. the law firm where he was a junior associate. And he’d asked me to lunch four times before I said yes because I had a strict policy about not dating lawyers, which looking back clearly didn’t hold up very well. The last line of the letter, don’t let her take what matters.

She can have the rest. Not instructions, not a scheme, just trust. Joel knew I was smart enough to understand what those words meant once I saw the second and third items in the envelope. Second, beneficiary confirmations. Joel had a life insurance policy, $875,000. He’d taken it out years ago at 30 when he first started the firm.

The bank had required it as collateral for his startup business loan. Back then, he was young and healthy, passed medical underwriting with no issues. The policy had been in place for 6 years. All Joel did in his final months was update the beneficiary. Changed it to me, Miriam Fredel, sole beneficiary. And here’s the key.

Updating a beneficiary on an existing life insurance policy does not require a new medical exam. It’s a form, one signature. Done. That $875,000 would pay directly to me when he died. It would never enter the estate, never go through probate. Carla could not touch it. Even if she knew about it, which she didn’t, she’d have no legal claim.

He’d done the same thing with his retirement accounts, a 401k with about 152,000 and a Roth EIR with about 58,000. Updated both beneficiary designations to me. Same principle. named beneficiary receives these directly outside of probate, outside the estate. That’s another $210,000 Carla couldn’t reach. I want to be clear about something.

This isn’t some secret loophole. This is how life insurance and retirement accounts work in every single state in America. Millions of families rely on this exact mechanism. Financial adviserss literally tell you to check your beneficiary designations every year. It’s not a trick. It’s Tuesday afternoon paperwork that most people put off and forget about.

Joel didn’t forget. Third, the real financial picture of Fredel and Associates. Joel had prepared a detailed summary handwritten in that precise lawyer script of his, laying out every debt, every liability, every ticking bomb inside his beautiful looking firm. And this is where I went from grieving widow to something else entirely.

The firm builds 620,000 a year. That part was true. That’s the number Joel mentioned at family dinners. The number Carla memorized like scripture. But here’s what 620,000 in revenue actually looked like once you peeled back the curtain. $15,000 in accumulated vendor and overhead debts. A pending malpractice settlement.

$180,000 already agreed to by Joel before he died. Just waiting for payment. 47,000 in unpaid payroll taxes. The IRS doesn’t forget about payroll taxes, by the way. They consider those trust fund taxes, meaning the responsible party is personally liable. And then the office lease, $34 months remaining at $4,200 a month.

That’s $142,800 in rent for a space you can’t walk away from. The house worth about $385,000, but Joel had taken out a $220,000 home equity line of credit 18 months ago to keep the firm afloat. Add that to the original mortgage balance of $ 160,000, and the total debt on the house was 360,000 after closing costs, realtor fees, and transfer taxes.

Selling that house would net exactly nothing, maybe less than nothing. And Carla’s precious $185,000 loan. She was an unsecured creditor. Do you know what that means? It means she’s last in line. Behind the IRS, behind the malpractice plaintiff, behind every vendor, every landlord, every creditor with a signed contract.

By the time all of them got paid, if they got paid, there’d be nothing left. Carla’s loan was gone the day Joel died. She just didn’t know it yet. I sat in that apartment doing the math on the back of a grocery receipt. My side, $1,85,000. Clean money, tax advantaged, non-probate, already mine. Carla’s side, approximately negative $520,000 once you added up every liability and subtracted every real asset.

The next day, Gail Horvath called me, Joel’s bookkeeper, the woman who’d managed his books for six years. Carla had fired her. the previous week. No severance, no notice. Just walked into the office and told Gail her services were no longer needed. After 6 years of keeping that firm’s books organized down to the penny, Gail was hurt and she was angry and Gail confirmed every single number in Joel’s summary.

She also told me something that made me close my eyes and just breathe. When Carla came to the office, she asked to see revenue reports. Gail printed them. Carla studied them carefully, nodded, and left. She never once asked about expenses. She never opened the liabilities folder. She looked at one column on one spreadsheet and decided she was inheriting a gold mine.

I called LRA the next morning. I said, “Don’t fight. Offer Carla everything. The house, the firm, every account in the estate. All I want is full sole custody of Tessa. No visitation for Carla.” LRA told me to come to her office. I brought Joel’s envelope. I laid it all out on her desk. The beneficiary forms, the financial summary, the math.

LRA read through everything. She checked the numbers twice. She looked at the insurance confirmation, the retirement account designations, the firm’s debt breakdown, and then LRA Schmidt, a woman who’d spent 20 years in estate law without flinching, leaned back in her chair and started laughing. Not a polite laugh, a real one, the kind where your eyes water and you have to take off your glasses to wipe them.

She looked at me and said two words. Joel was brilliant. Then she picked up her pen and started drafting the settlement offer. LRA contacted Axel Mendler the following week with an offer that on paper looked like a complete surrender. Miriam Fredel would relinquish all claims to estate assets, the firm, the house, every bank account connected to Joel’s name.

In return, Miriam wanted two things. Full sole custody of Tessa with no visitation rights for Carla. And Carla drops the will contest permanently. That’s it. Take the empire. Leave the child. Axel, to his credit, was suspicious. When someone hands you everything you asked for without a fight, any decent attorney starts looking for the trap.

He called LRA back and said he wanted more time. Specifically, he wanted a full forensic audit of the firm’s finances. He told Carla, “Give me 2 weeks to go through the books properly. 2 weeks. That’s all he asked for.” Carla said no. And here’s the thing, her reasoning wasn’t stupid. It was actually logical from her perspective.

She’d watched Miriam for seven years. She’d seen a quiet, polite woman who never argued, never pushed back, never raised her voice at a single holiday dinner. No matter how many times Carla called her Joel’s first wife or asked when she was going to do something with her career, in Carla’s mind, Miriam was finally doing what Miriam always did, folding.

And if you’re holding a winning hand and your opponent is trying to leave the table, you don’t say, “Wait, let me double check my cards.” You take the pot,” she told Axel. “I’ve seen the revenue, 620,000 a year. My son built that with my money. Get me those papers before she changes her mind.” Axel pushed back hard. He drafted a formal advisory letter, two pages single spaced, stating that due diligence on the firm’s financial position was incomplete and recommending that Carla wait for a full audit before accepting any transfer of assets and liabilities.

This is standard legal practice. Attorneys do this to protect themselves, and Axel was protecting himself beautifully. Carla read the letter, signed the waiver at the bottom acknowledging that she was proceeding against council’s recommendation, and told Axel to schedule the signing. There was one more thing.

Axel asked LRA directly, “Are there any non-estate assets we should be aware of, life insurance policies, retirement accounts with named beneficiaries?” LRA responded exactly as she should have. Non-estate assets are outside the scope of this estate settlement, and my client is under no legal obligation to disclose them.

Carla heard this through Axel and dismissed it immediately. Joel never mentioned life insurance to her. She assumed he didn’t have any. Why would he? He was 36. He was healthy, as far as she knew. Young men don’t think about life insurance. Except Joel did because a bank had required it 6 years ago. And Joel was the kind of man who kept paying premiums on time, even when everything else was falling apart.

While Carla was busy signing waiverss and ignoring her own attorney’s advice, I was quietly building my new life. The insurance company processed my claim in just under 3 weeks. $875,000 deposited directly into my personal checking account at a credit union in Florence, Kentucky. I’d opened that account specifically for this purpose.

No connection to any of Joel’s accounts, no connection to the estate. I also initiated the rollover on Joel’s retirement accounts. 152,000 from his 401k and 58,000 from his Roth IRA into accounts in my name only. I started moving things out of the house, nothing dramatic, a few boxes at a time. Tessa’s clothes and toys first, then my books, my documents, the photo albums.

I found a two-bedroom apartment in Florence about 20 minutes south of Covington. Clean, safe, good school district. First and last month’s rent was $1,800. I paid it out of my checking account and didn’t blink. Meanwhile, Spencer was living his best life. Carla had sent him to the firm to manage operations while the legal process played out, which mostly meant he sat in Joel’s chair, spun around a few times, and tried to figure out the phone system.

He called a process server, a delivery guy. He asked one of the parallegals what a retainer agreement was. On his third day, Carla had him go to the bank and sign onto the firm’s operating account as a co-signer so he could handle day-to-day expenses. Spencer signed every document the bank put in front of him without reading a single word.

He didn’t realize he was making himself jointly liable for obligations tied to that account. Spencer never read anything that didn’t have a screen and a controller attached to it. My mom came up from Lexington one more time. She sat across from me at my new kitchen table, a small IKEA table I’d assembled myself, which honestly felt like a bigger accomplishment than my entire marriage, and said, “Miriam, you’re giving up Joel’s house, his life’s work.

Are you having some kind of breakdown?” I wanted to tell her everything. I wanted to open my laptop and show her the bank balance and watch her eyes go wide, but I couldn’t. Not yet. Not until the papers were signed and there was no chance of anything leaking back to Carla through the small town telephone chain that connects every mother in Kentucky to every other mother within about 45 minutes.

So, I just said, “Mom, trust me, it’s going to be okay.” She didn’t believe me. I could see it in her face, but she hugged me anyway, and that was enough. The signing was scheduled for a Tuesday in late June. The night before, I laid out Tessa’s outfit for daycare, packed my bag with the signed apartment lease and a folder of bank statements showing $1,85,000 in clean assets, and set my alarm for 6:30.

I climbed into bed, pulled the covers up, and fell asleep in under 5 minutes. First time that had happened since March 6th. Axel Mendler’s office was on the third floor of a brick building on Pike Street in downtown Covington. Conference room with beige walls, industrial carpet, and a coffee machine that produced something technically brown and technically warm, but only theoretically coffee.

I arrived at 9:15 with LRA. We took the two chairs on the left side of the table and waited. Carla walked in at 9:20 with Spencer and Axel. She was dressed like she was accepting a lifetime achievement award. Full makeup, gold earrings, a cream silk blouse that probably costs more than my first month’s rent. Spencer wore a new navy blazer.

I noticed the price tag was still tucked inside the collar, hanging against the back of his neck like a little white flag. Nobody told him. I certainly wasn’t going to. The documents were straightforward. I Miriam Fredel hereby transfer all claims to the estate assets of Joel Fredel including but not limited to the law practice known as Fredel and Associates the residential property and all associated financial accounts to Carla Fredel who accepts said assets along with all associated liabilities.

In exchange, Carla relinquishes all claims regarding custody of Tessa Fredel and I receive full sole custody with no visitation rights for Carla or Spencer. LRA made one quiet statement before I signed. For the record, my client is signing voluntarily and wishes to confirm that the opposing party has reviewed and accepted the estate inclusive of all disclosed liabilities.

Axel confirmed. Carla didn’t even look up. She was already reaching for her pen. I signed. Carla signed. Spencer sat there grinning like he’d just been promoted to CEO of something. The whole thing took 8 minutes. Fastest 8 minutes of my life. And I once ran a half mile in high school gym class to avoid getting a B in physical education.

As I stood to leave, Carla couldn’t resist. She looked at me across the table and said she hoped I’d finally learn to stand on my own two feet without a freedle to lean on. Spencer nodded along, probably without understanding exactly what she’d said, but agreeing on principle because that’s what Spencer does.

I picked up my bag, walked out, collected Tessa from daycare at 3:15, and drove to our apartment. I made her macaroni and cheese from a box, the kind with the dinosaur shapes, because Tessa firmly believed dinosaur shaped pasta tasted better than regular pasta. And honestly, she might be right about that. We watched cartoons until 6:30.

She fell asleep on the couch with cheese on her chin. I carried her to bed. Then I sat on my kitchen floor with my back against the cabinet and just breathed. It was the most peaceful evening I’d had since Joel died. Three weeks later, Carla Fredel walked into Fredel and Associates as its legal owner and began running her new empire.

I wasn’t there to see it, but in a town like Covington, you don’t need to be. People talk. Gail still had friends at the office and some things I learned from Carla herself during that last phone call. So, here’s what happened. Day one, she opened a stack of mail that had been accumulating on Joel’s desk.

envelopes she’d walked past a dozen times without bothering to open. The third envelope was from the Internal Revenue Service. Notice of unpaid payroll taxes, $47,000, penalties acrewing monthly. Day three, a phone call from an attorney in Cincinnati representing the plaintiff in a malpractice suit against Joel. The settlement had been agreed upon before Joel’s death, $180,000.

Payment was overdue. The attorney was very polite and very firm. Day five, the building landlord called about the office lease. 34 months remaining. Carla needed to sign a personal guarantee to assume the lease in her name or vacate within 60 days. Carla signed the guarantee. She didn’t hesitate because in her mind, the firm made $620,000 a year and 4,200 a month in rent was nothing.

She just committed herself personally to $142,800 in future payments. Day eight, Carla finally tried to open Joel’s QuickBooks file. Without Gail Horvath, it was chaos. 6 years of categorized entries that made perfect sense to Gail and absolutely none to anyone else. Carla hired a temp accountant from a staffing agency.

The woman sat down, spent 4 hours clicking through files, and then turned to Carla with the expression of someone who just opened a door expecting a closet and found a staircase going straight down. She said, “Ma’am, are you aware there are over $115,000 in outstanding vendor invoices here, some of them dating back 14 months?” Day 10.

Gail Horvath filed a formal employment claim for wrongful termination without notice or severance. Six years of service. Estimated claim, $20,000. Carla called Axel Mendler that night. I don’t know exactly what she said, but I can imagine the pitch of her voice. That tea kettle frequency I’d come to know so well. Axel pulled up his files.

He read her his own advisory letter back to her. He reminded her about the waiver she’d signed. He said, “I recommended a full audit. You declined. I have documentation.” Then Carla called me. I saw her name on my phone screen glowing in the dark of my bedroom. I watched it ring four times. Then I set the phone face down on my nightstand and went back to sleep.

Carla hired a new attorney, a woman named Betsy Pulk out of a firm in Cincinnati. Someone with no connection to the case. Fresh eyes, sharp reputation. Carla told her the whole story. She said she’d been deceived, manipulated, tricked into accepting a worthless estate by her scheming daughter-in-law.

Betsy reviewed everything. The settlement agreement, the signed waiver, Axel’s advisory letter, the estate filings that LRA had prepared and disclosed before the signing. Every liability had been listed. Every debt was in the paperwork. Nothing was hidden. Nothing was fabricated. Miriam hadn’t lied about a single thing.

She simply hadn’t volunteered information about assets that were legally hers and legally outside the estate. Betsy reviewed everything and from what I heard later told Carla the truth in terms that left no room for hope. She was represented by competent counsel. She was advised to wait for a full audit. She refused. She signed a waiver.

The settlement was voluntary, mutual, and documented. No fraud, no case. Apparently, the exact words were, “What you have is not a legal claim. What you have is a very expensive lesson.” Carla tried to sell the house. Her realtor ran the numbers and delivered the news at her own kitchen table. After paying off the mortgage, the heliloc, closing costs, and agent commission, Carla would owe approximately $11,000 a closing.

The house wasn’t an asset. It was an exit fee. The IRS didn’t care about Carla’s feelings. Payroll tax penalties kept acrewing. Carla began dipping into her personal savings. Money she’d spent 30 years accumulating from her dry cleaning stores. She sold the Burlington location first, then the one in Erlanger.

Two stores gone in two months, and she still wasn’t close to covering the firm’s total liabilities. Spencer, who had been playing managing partner for exactly 19 days before the walls caved in, suddenly remembered he had somewhere else to be. He tried to remove himself as co-signer on the firm’s operating account.

The bank informed him that his signature created joint liability for certain obligations processed through that account, including a vendor payment plan that Carla had set up using the account after the transfer. Spencer hired his own lawyer. A 29-year-old man whose mother had been paying his cell phone bill for the last 6 years hired an attorney to sue that same mother, claiming she’d coerced him into signing bank documents he didn’t understand.

His case went nowhere. He’d signed voluntarily as an adult with no documentation of duress, but the lawsuit itself, Spencer Fredel versus Carla Fredel, was real. filed in Kenton County. Case number and everything. Mother and son, the inseparable team who’d stood in my kitchen measuring rooms and making plans were now paying separate attorneys to argue against each other.

I honestly couldn’t have written a better ending if I’d tried. And believe me, during those long nights in my apartment while Tessa slept, I’d imagined quite a few. The last time Carla called me, I answered. She was crying. Not the performative grief I’d seen at Joel’s funeral. Real tears, the messy kind, the kind you can hear through a phone.

She said she was losing everything. She said she didn’t know. She said she needed help. I listened. I didn’t interrupt. And when she finished, I said, “Carla, you stood in my kitchen and told me you wanted everything except my daughter. Do you remember that? You said you didn’t sign up for someone else’s child.

You wanted the house, the firm, every single dollar. And I gave you exactly what you asked for, every single piece of it. Then I hung up and I went back to helping Tessa glue macaroni onto a piece of construction paper because she’d decided she was making a portrait of a horse and she needed more noodles for the mane.

That night, after Tessa was in bed, I sat at my little IKEA table, the one I’d assembled myself with a YouTube tutorial and a butter knife because I couldn’t find the Allen wrench, and opened my laptop. I filled out the application for a parallegal certification program at Gateway Community College. Tuition was $4,200 a semester.

My bank account had $1,85,000 in it. I could afford it. On my nightstand, framed in a simple black frame I’d bought at a craft store for $6, was Joel’s letter. I read the last line every night before I turned off the light. Don’t let her take what matters. She can have the rest. Thank you so much for staying with me through this whole story.