I never meant to look into this. It started with a simple genealogy project, the kind millions of people do every year. Tracing family trees, searching old records, finding ancestors, normal stuff. But somewhere between the census data and the immigration papers, I found something that didn’t fit.

a pattern, not in one family line, but in dozens, hundreds maybe. And the deeper I looked, the less sense any of it made. Names changed, not gradually, not through marriage or natural linguistic drift, but suddenly, completely. Within a single generation, sometimes within a single year, entire family identities were rewritten.

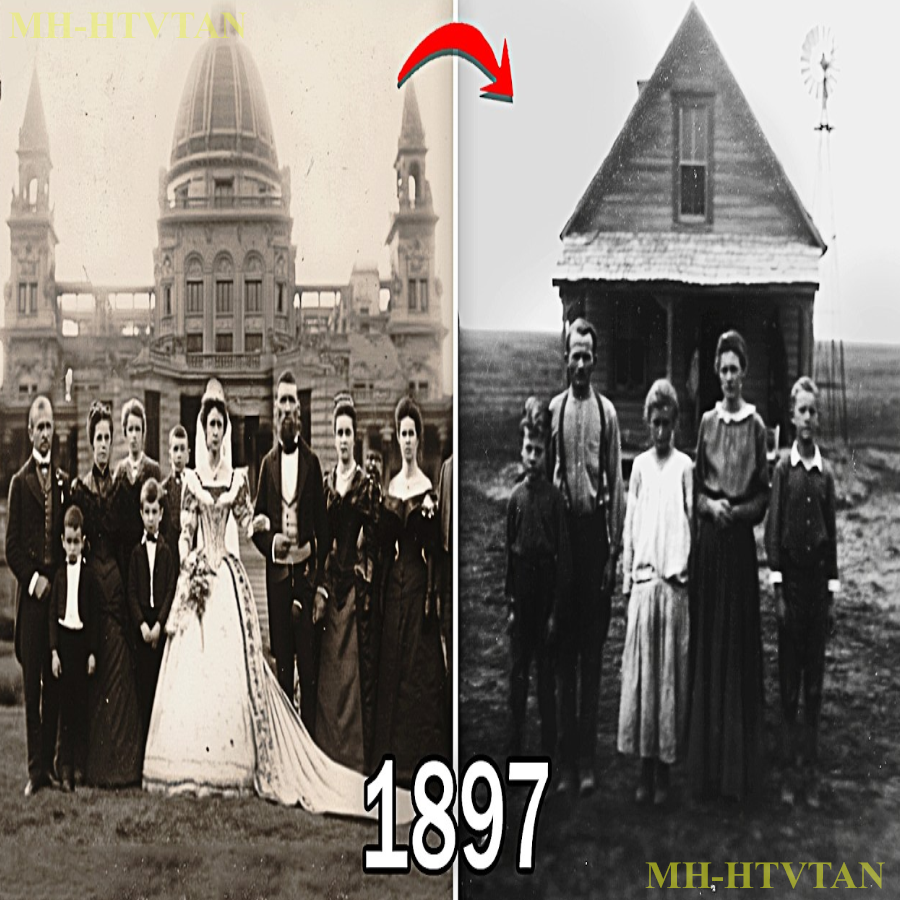

The official explanation, immigration, assimilation, clerical errors. But what if it wasn’t that simple? What if these weren’t random changes at all, but coordinated erasers? Deliberate acts designed to sever entire populations from a heritage they were never supposed to remember. Let me show you what I found. In the United States between roughly 1880 and 1920, immigration records show something peculiar.

Families arriving from Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and parts of Russia came with one set of names, complex surnames with unusual suffixes, linguistic structures that didn’t match the regions they claimed to be from. Then within months, sometimes within weeks of processing through Ellis Island or other ports of entry, those names changed, not shortened, not anglicized in the typical way we understand it, replaced.

A man named Tartikov becomes Thompson. A woman named Tartarescu becomes Taylor. Children with the surname Tartaran are registered in school records as Turner, Travis, or Thomas. And this happens not to one family but to thousands across multiple entry points across decades. The official narrative tells us this was voluntary that immigrants chose to adopt new names to fit in to avoid discrimination to start fresh in a new world. And sure that happened.

Plenty of documentation supports it. But this this was different because the pattern repeats with unsettling precision. For those unfamiliar with the Tartarian theory, here’s the foundation. Researchers claim there was an advanced civilization, call it Tartaria, call it the old world, that existed until relatively recently.

We’re not talking ancient history. We’re talking the 1800s. This civilization supposedly left behind architectural evidence that official history struggles to explain. elaborate structures, consistent design principles, advanced engineering, and they appear everywhere. San Francisco, St. Petersburg, Melbourne, Buenosarees, Kolkata.

Buildings that share the same architectural language, the same level of sophistication, the same curious detail. First floors buried underground, windows half submerged as if some catastrophic event, a mud flood, covered the original ground levels. The mainstream explanation, different architects, different eras, convergent design trends.

But here’s what made me connect the architecture to the name changes, the timing. The same period when families were erasing their Tartarian surnames, roughly 1870 to 1920, coincides almost exactly with when these magnificent buildings start being attributed to local architects with conveniently complete paper trails. When World’s Fair suddenly showcase technologies that seem to appear from nowhere only to vanish just as quickly.

When old maps stop mentioning Tartery as a place, the buildings remain. The mud flood evidence remains. The architectural mysteries remain. But the people who might have built them. Their names were changed. And that’s not a coincidence. It can’t be because if you erase the names, you erase the builders. If you erase the family lines, you erase the knowledge of who actually created these structures.

The pattern repeats with unsettling precision. Wherever you find Tartarian architectural evidence, you find genealogical erasers in the same approximate time frame. Same phenomenon, same locations, same systematic silence. If you think this was just an American phenomenon, look at Europe. In the 1890s and early 1900s, census records across France, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and the Russian Empire show similar discontinuities.

Families with surnames rooted in what researchers describe as Tartar or Tartarian linguistic origins suddenly vanish from administrative records. Not because they died, not because they moved, they simply became other people. The Tartacovs of Moscow appear in the 1880 census. By 1897, they’re the Terasovs.

Different name, same address, same profession. No explanation in the records. In Prussia, a family named Tartenberg appears in property records for three generations, 1820, 1850, 1870. Then in 1891, the property is listed under the name Tannenburgg. Same parcel, same family structure. The transition documentation missing.

This raises a simple but critical question. Why would families with established names, property rights, and social standing, voluntarily erase their identitiesacross multiple countries, all within the same narrow time window, all without proper documentation, and all while pretending nothing had changed. The deeper I went, the more I found.

France, Italy, Spain, Poland, Romania. The pattern repeats. If you’re finding this research valuable, consider subscribing or becoming a YouTube member. This kind of investigative work takes time, and your support helps keep these forgotten histories from staying buried. And here’s where it gets stranger. In China and Mongolia during the lateqing dynasty, administrative reforms between 1880 and 1910 included widespread standardization of family names.

Official records described this as modernization, a way to streamline census data and taxation, but the specifics tell a different story. Families in regions historically associated with Tarta populations, Inner Mongolia, Manuria, parts of Shing Jang, saw their ancestral surnames replaced with Han Chinese equivalents, not transliterated, replaced, and the old names erased from official records.

In Japan during the Maji restoration, similar reforms took place. The surname edict of 1875 required all citizens to adopt formal family names. But what’s rarely discussed is how many existing names, particularly those with connections to the Inu or northern Tarta influenced regions, were quietly eliminated from registries and replaced with approved alternatives.

Why? Why the urgency? Why the coordination? Why the silence? The Ottoman Empire presents perhaps the most glaring anomaly. For centuries, the Ottoman administrative system maintained detailed population records, tax registers, military conscription lists, property deeds. These documents are remarkably comprehensive, except for one thing.

Between approximately 1870 and 1920, records of families with Tarta or Tartarian surnames become increasingly sparse, not absent, sparse. And when they do appear, they’re often noted as having adopted new surnames under various reform edicts. The old names simply stop appearing. But here’s the thing.

The Ottoman Empire was multilingual, multithnic, and relatively tolerant of diverse naming conventions. Greeks kept Greek names. Armenians kept Armenian names. Slaves, Arabs, Kurds, all maintained their linguistic and familial identities. So why did Tarta names need to disappear? The official explanation collapses here. If assimilation and modernization were the goals, why target this specific ethnic linguistic group so systematically while leaving others intact? Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. We’re talking about a phenomenon

that spans multiple continents, dozens of countries, and vastly different political systems, monarchies, empires, emerging democracies, colonial administrations. And yet within the same approximate time frame, all of these systems implemented similar policies that resulted in the same outcome.

The systematic eraser of Tartar and Tartarian surnames from official records. No international treaty mandated this. No global conference coordinated it. No single power controlled all these territories simultaneously. And yet it happened everywhere all at once. This is the coordination problem. How does something like this occur without central organization, without documentation, without anyone anywhere questioning why entire family lineages were being rewritten? The evidence suggests something much larger than bureaucratic coincidence or

organic cultural change. If this research is making you question what we’ve been told, you’re not alone. Leave a comment with your thoughts. I read everyone and your insights help shape future investigations. Perhaps the most haunting aspect of this entire phenomenon is the silence. When other ethnic groups faced persecution or forced assimilation, there were protests, uprisings, documentation of resistance, letters, diaries, newspaper articles, some record of people saying this is wrong. This is happening to us.

But for the tartar and name changes, nothing. No documented resistance, no recorded protests, no family letters saying, “The authorities forced us to change our name, no newspaper articles decrying the eraser of cultural heritage.” The silence was deafening. And that silence raises more questions than any answer could resolve.

Were people threatened into compliance? Were the changes so normalized, so embedded in bureaucratic routine that no one thought to resist? or is the documentation simply missing, removed, destroyed, or hidden in archives we haven’t accessed? We don’t know. And that’s where the official narrative becomes impossible to ignore.

Not because of what it explains, but because of what it refuses to address. If you search for academic studies on this phenomenon, you’ll find almost nothing. Not not much. Almost nothing. There are papers on immigration and name changes, studies on assimilation, linguistic analyses of surname evolution, all valid, all well researched.

But on this specific pattern, the coordinated eraser ofTartar and Tartarian surnames across multiple continents within a specific time window. Silence. A few scattered references. A footnote here. A passing mention there. But no comprehensive study. No historian asking why did this happen? No sociologist examining the scale and coordination.

No genealogologist mapping the systematic nature of the erasers. It’s as if the academic community collectively decided this wasn’t worth investigating or couldn’t investigate or was subtly discouraged from investigating. The deeper I went, the more doors closed, archival materials suddenly unavailable. Records lost in fires.

Entire genealological databases with inexplicable gaps in exactly the years and regions where these name changes occurred. Not everywhere. Not all the time, but enough. Enough to notice. Enough to wonder. Names aren’t just labels. They’re markers of origin, carriers of history, links to ancestral lands, and forgotten peoples.

When you change a name, you don’t just alter a word. You sever connections. You make it harder for descendants to trace their lineage. You erase linguistic clues that might point to a different history than the one officially recorded. And if you do this systematically across generations across continents, you can effectively erase an entire heritage from collective memory.

Within three generations, no one remembers the old names. Within five, no one knows to look for them. Within seven, the very idea that there was something to look for seems absurd. Is that what happened? Did an entire cultural identity get systematically dismantled through something as simple as name changes? And if so, why? What were they hiding? What heritage was so dangerous that it needed to be erased not through violence or conquest, but through paperwork and bureaucracy? Some traces remain.

In remote villages across Siberia, Mongolia, and Central Asia, you can still find elderly people with surnames that carry the old linguistic markers. Tartacov, Tataski, Tatarescu. names that according to official histories shouldn’t exist or should have naturally evolved into something else by now. But they didn’t.

They persisted in isolated pockets in places where bureaucratic reach was limited. Where the reforms didn’t fully penetrate, where families held on to their names despite pressure to change. And when you talk to these people or read the few ethnographic studies that document their stories, a common thread emerges. their grandparents or great-grandparents spoke of a time when everyone had these names.

When Tarta surnames were common, unremarkable, normal. Then something changed. Authorities came. Papers were issued. Names were recorded differently. And slowly, quietly, the old names faded. Not by force, not through violence, through administration, through paperwork, through the simple bureaucratic act of writing a different name in a ledger.

And here’s the strangest part. No one seemed to think it was worth mentioning. You might be wondering, what does any of this have to do with architecture, with the grand buildings and advanced infrastructure that other researchers associate with Tartaran theories? Everything. Because if you erase the names, you erase the builders.

If there’s no record of people with Tartaran heritage, then those people couldn’t have built anything. They couldn’t have possessed advanced knowledge. They couldn’t have been part of a sophisticated civilization. They simply didn’t exist. And without the names, without the genealogical paper trail, there’s no way to connect modern descendants to whatever came before.

No way to claim inheritance, literal or cultural. No way to say my ancestors built that. The architectural mystery and the genealogical eraser may be two sides of the same coin. Erase the names and you erase the claim to the structures. Erase the family lines and you erase the knowledge those families might have carried. It’s elegant in a horrifying sort of way.

You don’t need to destroy buildings. You just need to ensure that no one alive can prove their ancestors built them. The more I researched, the more I realized this wasn’t just about names. It was about memory. cultural memory, ancestral memory, collective memory, all of it systematically severed through a process that on the surface looked perfectly reasonable.

Immigration, modernization, administrative efficiency. But strip away the justifications and you’re left with an uncomfortable reality. Entire populations were disconnected from their heritage within living memory, and no one seemed to notice or care. How how does something that massive happen without mass awareness? The answer, I think, is that it was normalized, bureaucratized, turned into routine.

Each individual case seemed reasonable in isolation. A name change here, a clerical adjustment there. Nothing sinister, nothing worth questioning. But when you step back and look at the aggregate, it’s staggering. So, what actually happened? I don’t havedefinitive answers. No one does. That’s the point.

But I can tell you what the evidence suggests. Between roughly 1870 and 1920, there was a coordinated global effort to erase Tartar and Tartarian surnames from official records. This effort spanned multiple continents, involved dozens of countries with vastly different political systems, and occurred with almost no documented resistance or public acknowledgement.

Why? What were they hiding? What heritage was so dangerous that it needed to be systematically erased not through violence but through bureaucracy? Was there a global directive we don’t know about? An unspoken agreement among world powers to rewrite certain genealogies? Or was this something even stranger? A kind of cultural self-eria where the descendants of Tartaria themselves chose to forget? And if so, what did they know that we don’t? Names carry stories.

Lineages preserve knowledge. When you erase both, what else disappears with them? Building techniques, organizational structures, historical events that don’t fit the approved narrative. We’ll never know because the people who might have passed that knowledge down were systematically disconnected from their past.

Their children were given new names, new origins, new stories. And within a few generations, the old knowledge simply vanished. Not destroyed, forgotten. There’s a difference. And that difference haunts me because somewhere in dusty archives and forgotten documents, the truth might still exist. The original names, the family records, the connections between modern populations and whatever came before.

But finding it, proving it, that’s the challenge. And maybe that’s exactly how it was designed to work. I started this investigation looking for ancestors. What I found was a void, a carefully constructed, bureaucratically maintained void where an entire heritage used to be. And I can’t stop asking why.

Why go to such lengths? Why coordinate such a massive effort across so many countries? Why erase these names and not others? What were they so afraid of us discovering? The official history offers no answers, only silence, only gaps, only the persistent, maddening refusal to acknowledge that something happened, something big enough, important enough, threatening enough that it required a global effort to erase.

And that’s what keeps me digging. Not because I have answers, but because the questions won’t let me go. Because once you see the pattern, once you notice the coordinated erasers and the impossible coincidences and the deafening silence, you can’t unsee it. And you can’t stop wondering what we lost when they changed the names.