The dusty corner of Hartford Historical Society held countless forgotten treasures, but none captured Dr. Sarah Mitchell’s attention quite like the ornate wooden frame propped against a filing cabinet. The CPAoned wedding portrait from 1903 showed what appeared to be a typical Victorian ceremony, a stern-faced groom in his finest black suit standing beside his bride, who wore an elaborate white gown with intricate lace details.

Sarah, a photography historian specializing in early American portraiture, had seen thousands of similar images. The formal poses, the stoic expressions, the careful arrangement of hands and fabric, everything seemed perfectly ordinary for the era. The bride’s face bore the expected serious demeanor common in photographs of that time, when long exposure times made smiling impractical.

But something nagged at Sarah as she lifted the frame closer to the window. The late afternoon, Connecticut sun streamed through the glass, illuminating details that hadn’t been visible in the dim archive room. She adjusted her glasses and squinted at the image, feeling an inexplicable pull toward the bride’s face.

“Just another wedding portrait,” she murmured to herself. Yet her fingers traced the edge of the frame as if drawn by an invisible force. The photograph bore a small handwritten inscription on the back. Thomas and Elizabeth, June 15th, 1903. Hartford. No surname, no photographers’s mark. No other identifying information. The couple appeared prosperous.

the quality of their clothing and the professional nature of the photograph suggested they were from Hartford’s growing middle class. As Sarah prepared to set the portrait, aside with dozens of others awaiting cataloging, a shaft of sunlight hit the glass at precisely the right angle for just a moment. Something in the bride’s expression caught her eye, something that shouldn’t have been there, something that defied everything she knew about early 20th century photography and social customs.

Her heart began to race as she realized this ordinary portrait might be hiding an extraordinary secret. Sarah’s hands trembled slightly as she carried the portrait to her desk, positioning it under the adjustable lamp she used for detailed photograph analysis. She reached for a magnifying glass, a tool that had revealed countless hidden details in historical images over her 15-year career.

The bride’s face, which had seemed typically solemn from a distance, began to reveal something remarkable under magnification. Sarah blinked hard, certain her eyes were playing tricks on her. She adjusted the focus and leaned closer, her pulse quickening with each passing second. There, barely visible but unmistakably present, was something that should have been impossible in 1903.

The bride was smiling, not the practiced posed expression of later decades, but a genuine subtle upturn of her lips that spoke of barely contained joy or perhaps amusement. “That can’t be right,” Sarah whispered to the empty archive room. Victorian era photography required subjects to hold still for several seconds due to long exposure times.

Smiling was not only impractical but considered improper for formal portraits, especially wedding photographs. The social conventions of 1903, Hartford would have demanded the serious, dignified expression typical of the era. Sarah studied the technical aspects of the photograph. The clarity was exceptional, far superior to most amateur photography of the time.

The lighting was professionally arranged, suggesting an established photographer’s studio. Yet here was this bride, clearly breaking every rule of proper portrait etiquette. She examined the groom’s expression, stern and appropriate for the period. His posture remained rigid and formal. Everything about him screamed conventional Victorian propriety.

But Elizabeth seemed to be sharing a secret with the camera, or perhaps with someone just beyond the photographers’s shoulder. Sarah pulled out her laptop and began researching Hartford wedding photographers from 1903. Cross-reerencing studio locations with the background elements visible in the portrait. The wallpaper pattern, the furniture placement, even the specific style of carpet beneath their feet might provide clues about where this impossible photograph had been taken.

The mystery was deepening with every detail she discovered. The next morning found Sarah at Hartford’s main library, surrounded by dusty volumes of city records and historical newspapers from 1903. She had barely slept, her mind racing with possibilities about the smiling bride. Professional curiosity had evolved into genuine obsession.

The Hartford currents wedding announcements from June 1903 yielded nothing for a Thomas and Elizabeth married on the 15th. She expanded her search to surrounding towns, West Hartford, East Hartford, Bloomfield, but found no matching records. It was as if this couple had never existed in any official capacity. Excuse me. Sarah approachedthe librarian, Mrs.

Peterson, who had worked at the Hartford Library for over 30 years. I’m researching a couple from 1903, Thomas and Elizabeth. They were married on June 15th. Do you know of any other sources I might check? Mrs. Peterson adjusted her reading glasses thoughtfully. Have you tried the church records? Many ceremonies weren’t always reported in the newspapers, especially if they were smaller affairs.

Trinity Episcopal keeps excellent records. The Catholic churches have archives dating back to the 1890s. Sarah spent the afternoon visiting churches throughout Hartford. At Trinity Episcopal, Reverend Williams led her to their basement archive where leatherbound marriage registers sat in climate controlled cases.

June 1903, he murmured, running his finger down the handwritten entries here. June 13th, Thomas Martin and Elizabeth Hayes. June 20th, Thomas Richardson and Elizabeth Collins. But nothing on the 15th with just first names. What about unusual circumstances? Sarah asked. Anything that might have required discretion or privacy? Reverend Williams paused, considering her question carefully.

There were occasionally marriages that weren’t, shall we say, conventional. Perhaps a pregnant bride or couples from different social classes. Such ceremonies might have been conducted quietly with minimal documentation. Sarah’s pulse quickened. Could Elizabeth’s mysterious smile be hiding a secret that required such discretion? As she walked back to her car in the late afternoon Connecticut sun, she couldn’t shake the feeling that she was on the verge of uncovering something far more significant than a simple photographic

anomaly. Back at the historical society, Sarah decided to examine every inch of the portrait and its frame with scientific precision. She carefully removed the photograph from its frame, hoping to find additional clues on the backing or hidden within the mounting materials. Her patience was rewarded. Tucked between the photograph and the cardboard backing was a small piece of folded paper yellowed with age.

Sarah’s hands shook as she unfolded it, revealing a brief note written in faded ink. My dearest Thomas, by the time you read this, I will be far from Hartford. The photographs must tell the story I cannot look for what others cannot see. Remember our signal. Forever yours. E. Sarah stared at the cryptic message, her mind racing with possibilities.

Our signal? Could this refer to the smile? Was Elizabeth trying to communicate something through her expression that conventional Victorian society wouldn’t permit her to say aloud? She examined the photograph again with fresh eyes, this time looking for other anomalies. Under high magnification, she noticed Elizabeth’s left hand partially hidden by the folds of her wedding dress.

Her fingers appeared to be positioned in an unusual way, not the typical formal placement expected in wedding portraits. Sarah photographed the hand position with her digital camera and began researching Victorian sign language and secret communication methods. Her search led her to fascinating discoveries about how women of the era sometimes communicated covertly through fan language, flower arrangements, and hand positions.

In a 1902 etiquette book, she found a reference to finger telegraphs, discrete hand signals used by women to convey messages in social situations where direct communication was inappropriate. According to the guide, specific finger positions could indicate danger, affection, or urgent messages. Elizabeth’s finger position matched one of the illustrations.

a warning signal meaning help or not what it appears to be. Sarah leaned back in her chair, the implications washing over her. This wasn’t just an unusual wedding portrait. It was a desperate woman’s attempt to leave evidence of something terrible. Elizabeth’s smile wasn’t joy or amusement. It was a brave mask covering fear, and her hidden hand signal was a cry for help that had gone unnoticed for over 120 years.

Armed with Elizabeth’s note and her newfound understanding of the photographs, hidden messages, Sarah expanded her investigation beyond marriage records to missing person reports and news articles from the summer of 1903. She combed through police records, hoping to find any mention of a woman named Elizabeth, who had disappeared around the time of the photograph.

Her breakthrough came from an unexpected source, the Hartford Currents Society Pages from July 1903. buried in a small column about summer social activities was a brief mention. Now, the ladies of the Hartford Women’s Auxiliary expressed concern for Mrs. Elizabeth Hayes, who failed to attend the quarterly charity lunchon despite having confirmed her attendance.

Elizabeth Hayes, one of the names Reverend Williams had mentioned from Trinity Episcopal’s marriage register, but that ceremony was recorded on June 13th, 2 days before the date inscribed on the portrait. Sarah rushed back to Trinity Episcopal, her heart poundingwith anticipation. Reverend Williams retrieved the marriage register again, and this time Sarah studied the entry more carefully.

The handwriting was different from the other entries, the ink slightly darker, as if it had been added later. Reverend Williams, is it possible this entry was made after the fact, perhaps backdated? He examined the page closely, his expression growing concerned. It’s possible. In 1903, there were occasionally marriages that needed to be regularized for legal purposes.

If a couple had wed in a civil ceremony or under unusual circumstances, they might later register with the church to avoid social scandal. Sarah’s investigation led her to the Hartford Police Department’s historical files, housed in the basement of city hall. Officer Martinez, a young policeman with an interest in local history, helped her navigate the maze of filing cabinets containing records from the early 1900s.

Missing person reports from 1903, he muttered, pulling out a thick folder. We’ve got quite a few. Hartford was growing rapidly then. Lots of people coming and going. Sarah’s eyes widened as she spotted a report dated July the 20th, 1903. Elizabeth Hayes, age 23, reported missing by her sister Margaret. Last seen at home on July 15th.

Brown hair, green eyes, approximately 5’4 tall. Family reports unusual behavior in weeks prior to disappearance. The missing person report included Margaret’s address on Asylum Street. In what had been Hartford’s most fashionable neighborhood in 1903, Sarah discovered that the original Victorian house still stood, now converted into apartments.

The current owner, an elderly man named Robert, invited her in when she explained her historical research. The Hayes family, you say? Robert nodded thoughtfully. I’ve lived here 40 years. The previous owner mentioned finding some old papers in the attic when he renovated. Might still be up there. In the dusty attic, beneath layers of insulation installed decades later, Sarah found a small wooden trunk.

Inside were personal letters, photographs, and documents belonging to the Hayes family. Her hands trembled as she opened a diary with Margaret Hayes written on the cover in careful script. The entries from summer 1903 painted a disturbing picture. June 10th, 1903. Elizabeth has been acting strangely since she met that man, Thomas.

She speaks little of him, only that they plan to marry. I have not been introduced, which is most unusual for my dear sister. June 16th, 1903. Elizabeth returned from her wedding ceremony changed. She smiles when she thinks no one is watching, but her eyes hold fear. She begs me not to ask questions about Thomas or their living arrangements. July 1st, 1903.

I followed Elizabeth today and discovered she has not been living with Thomas as she claimed. Instead, she rents a small room above Mrs. Patterson’s bakery on Main Street. When I confronted her, she broke down and confessed the marriage was arranged to help her escape some terrible situation. She would not explain further. July 14th, 1903.

Elizabeth came to me tonight in great distress. She said Thomas was not who he claimed to be and that she had discovered something that put her in danger. She spoke of leaving Hartford immediately and asked me to keep a photograph she said would explain everything if something happened to her. I begged her to go to the police, but she said they would not believe her.

July 21st, 1903. My sister has vanished. I have reported her missing, but the police seem disinterested. They suggest she may have simply left with her husband, despite my insistence that Thomas is equally missing and that their marriage was unusual from the beginning. Sarah’s hands shook as she closed the diary.

Elizabeth’s smile on the wedding portrait wasn’t capturing joy. It was the brave face of a woman documenting evidence of danger, knowing it might be the last record of her existence. Margaret’s diary provided crucial clues about Thomas. But Sarah needed more concrete information about the mysterious groom. She returned to the 1903 Hartford City directory.

This time, searching for every Thomas listed and cross-referencing their occupations and addresses. One entry caught her attention. Thomas Miller, private detective, office at 245 Main Street. The address was just three blocks from Mrs. Patterson’s bakery, where Margaret had discovered Elizabeth was secretly living.

Sarah’s research into private detectives in 1903, Hartford revealed a fascinating and often murky profession. Private investigators of that era frequently worked on behalf of wealthy families, sometimes to resolve scandals discreetly or to track down individuals who had information valuable to their clients.

At the Hartford History Museum, Sarah found a collection of business cards and advertisements from the period. Thomas Miller’s card was preserved in a display about early 20th century professions. Thomas Miller, discrete investigations, recovery ofmissing persons and valuable items, confidential consultations available. The museum curator, Dr.

James Walsh, had extensive knowledge about Hartford’s business community from that era. Private detectives in 1903 operated in a gray area, he explained. Some were legitimate professionals helping families find lost relatives or investigating fraud. Others were essentially hired thugs working for whoever paid them.

What kind of cases might have involved a young woman like Elizabeth? Sarah asked. Dr. Walsh considered her question carefully. Wealthy families sometimes hired investigators to retrieve weward daughters or to recover stolen property or documents. There were also cases involving blackmail. Investigators might be hired either to prevent it or to facilitate it.

Sarah’s stomach tightened. Could Elizabeth have been a target rather than a willing bride? The evidence was beginning to suggest that the wedding portrait wasn’t documenting a marriage at all, but rather some kind of coercive situation. Her research into Thomas Miller revealed more disturbing details.

A Harvard Current article from September 1903 reported his death in what was described as a tragic accident at the railroad yards. The brief article mentioned that Miller had been investigating a case involving missing documents when he allegedly fell from a moving freight car. The timing was suspicious. Just two months after Elizabeth’s disappearance, Sarah was beginning to suspect that both Elizabeth and Thomas had become victims of something far more dangerous than a simple missing person case.

Sarah’s investigation had reached a critical juncture. She needed to understand what Elizabeth might have known or possessed that would put her in such danger. Margaret’s diary mentioned that Elizabeth had discovered something about Thomas, but provided no details about what that discovery might have been. Returning to the historical society archives, Sarah broadened her search to include major news stories from 1903 Hartford.

She was looking for any events that might have required the services of a private detective and could have inadvertently involved Elizabeth. Her persistence paid off when she discovered a series of articles about a major embezzlement scandal at Hartford National Bank in May 1903. Approximately $50,000 had vanished from the bank’s accounts, an enormous sum equivalent to over $1.5 million today.

The bank’s president, William Thornton, had hired private investigators to recover the missing out funds and identify the thief. One of the investigators mentioned in the coverage was Thomas Miller that Sarah’s pulse quickened as she pieced together the timeline. The embezzlement was discovered in early May. Thomas was hired to investigate.

Elizabeth’s diary entries suggest she met Thomas in late May or early June. Their wedding portrait was dated June 15th. Elizabeth disappeared in July and Thomas died in September. But who was Elizabeth in all of this? Sarah returned to Margaret’s diary, reading more carefully for any clues about Elizabeth’s employment or social connections.

She found her answer in an entry from spring 1903. Elizabeth has secured a position as a secretary at Hartford National Bank. She is quite excited about the opportunity as it pays well and the work is respectable for young woman. Sarah’s heart raced. Elizabeth worked at the bank where the money was stolen. She likely had access to records, transactions, and information that could identify the real thief.

If she had discovered something that contradicted Thomas’s investigation, or worse, if she had evidence that Thomas himself was involved in the embezzlement, her life would indeed have been in serious danger. The wedding portrait began to make perfect sense. Thomas had used a fake marriage ceremony to gain Elizabeth’s trust and get close to her.

Elizabeth, realizing she was in danger, had used the portrait session to document evidence of her situation. Her forced smile hiding fear, her hand signal calling for help, and her note to be discovered later as proof of what had really happened. Sarah knew she needed to find official records of the embezzlement investigation to confirm her theory.

The Hartford Public Libraryies newspaper archives contained extensive coverage of the bank scandal, including details about the investigation’s progress through the summer of 1903. A breakthrough article from August 1903 revealed that the investigation had taken an unexpected turn. The missing $50,000 had been traced to a series of forged documents and falsified transactions.

But the evidence pointed not to a bank employee, but to someone with intimate knowledge of the bank’s procedures and access to official documentation. The article quoted bank president Thornon. We have discovered that our investigation was compromised from within. The individual we trusted to find the thief appears to have been the perpetrator himself, using his position to cover his tracks whilecontinuing to steal from our institution. Sarah’s theory was correct.

Thomas Miller hadn’t been investigating the embezzlement. He had been committing it, using his role as a private detective to gain access to bank records and forged the documents needed to steal the money. But Elizabeth had figured it out. As a bank secretary, she would have had access to the original records and could have spotted the discrepancies between Thomas’s reports and the actual transaction documents.

The final piece of the puzzle came from a September 1903 police report Sarah found in the city hall archives after Thomas Miller’s death at the railroad yards. Police had searched his office and living quarters. They discovered $30,000 in cash hidden in a false bottom of his desk drawer along with forged bank documents bearing Elizabeth’s signature.

Police note attached to the report provided the chilling final detail evidence suggests Miller forced Miss Hayes to sign documents authenticating his fraudulent transactions. Her disappearance likely occurred when she threatened to expose his scheme. Miller’s death appears to be suicide rather than accident, possibly to avoid arrest and prosecution.

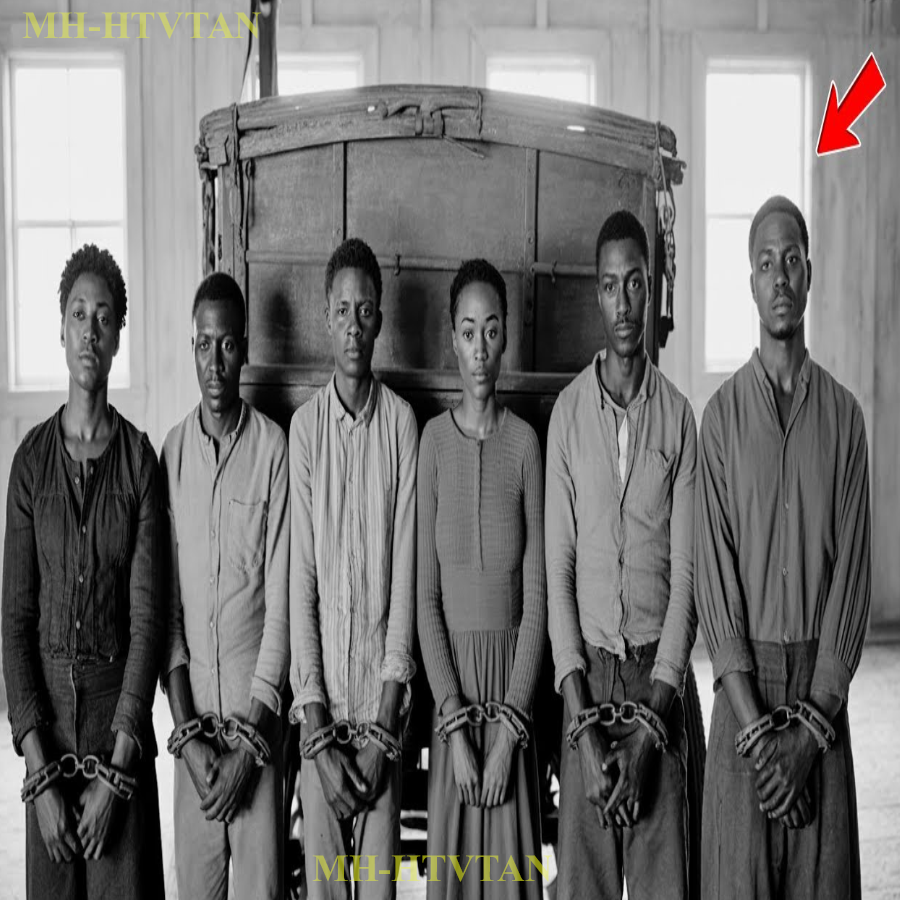

Sarah leaned back in her chair, overwhelmed by the tragic story she had uncovered. Elizabeth hadn’t been Thomas’s willing bride. She had been his victim, coerced into helping with his embezzlement scheme and then eliminated when she became a threat. The wedding portrait wasn’t a celebration. It was Elizabeth’s desperate attempt to leave evidence of her situation, knowing that Thomas intended to silence her permanently.

Sarah’s investigation had revealed a tragic story of courage and victimization that had been buried for over 120 years. Elizabeth’s cleverly hidden messages in the wedding portrait, her brave smile masking terror, her secret hand signal calling for help, and her note pointing toward the truth had finally been understood.

But Sarah’s work wasn’t finished. She felt a deep responsibility to ensure that Elizabeth’s story was told and her bravery recognized. She prepared a comprehensive report documenting her findings and contacted the Hartford Current, hoping they would publish Elizabeth’s story as a historical feature.

The newspaper’s editor, Maria Rodriguez, was fascinated by the investigation. This is exactly the kind of historical mystery our readers love, she said. But more importantly, it’s a story about a woman who showed incredible courage in impossible circumstances. Sarah also reached out to genealogy websites, hoping to locate any living descendants of the Hayes family who might want to know about Elizabeth’s fate.

Her search led to Patricia Hayes, a great great niece living in Boston, who had always wondered about the family stories of an ancestor who had disappeared mysteriously in Hartford. “We always heard whispers about Aunt Elizabeth,” Patricia said during their phone conversation. “My great-g grandandmother used to say that Elizabeth had tried to help catch a bad man, but got in trouble for it.

I never knew if it was true.” Patricia traveled to Hartford to see the portrait and learn about her ancestors story. Standing in the historical society, looking at Elizabeth’s photograph with new understanding, she wiped away tears. She was so young, Patricia whispered. But she was trying to do the right thing, even when it put her in danger.

Sarah arranged for the portrait to be properly preserved and displayed at the Hartford History Museum with a plaque telling Elizabeth’s complete story. The exhibit would ensure that visitors understood both the historical context of early 20th century banking fraud and the personal courage of one young woman who refused to remain silent about corruption.

Sarah looked at Elizabeth’s portrait one final time before it was moved to the museum. She marveled at how one woman’s desperate message, hidden in plain sight for over a century, had finally revealed the truth. Elizabeth’s smile, once a mystery, now stood as a testament to her bravery. A reminder that sometimes the most ordinary photographs hold the most extraordinary stories, waiting for someone willing to look closely enough to see what others had missed. Elizabeth’s legacy lived on.

Her story finally told.