In the spring of 1843, a Charleston physician named Dr. Nathaniel Peton was summoned to examine a patient at the Ravenswood estate, 3 mi north of the city. The call came at dawn, unusual timing that suggested urgency, but when Peetton arrived, he found no medical emergency.

Instead, he was led to a private study where the estate’s owner, a man named Cornelius Ashford, presented him with a leatherbound medical journal and asked a single question that would haunt Peton for the rest of his life.

Can a human being be bred like livestock across generations to enhance specific physical traits? The journal contained measurements taken over 26 years documenting three generations of systematic human breeding. Height, weight, bone density, muscle circumference, carrying capacity, resistance to disease.

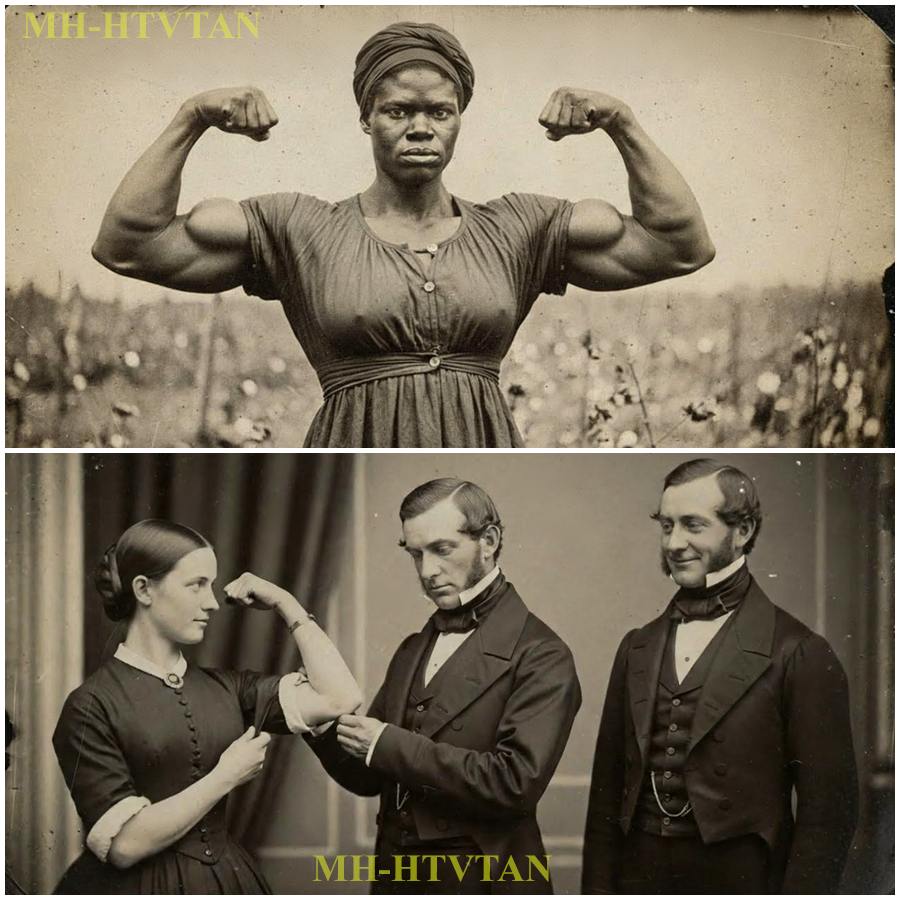

Every metric recorded with scientific precision. But what disturbed Peton most deeply wasn’t the measurements themselves. It was the photograph tucked between the journal’s final pages. a dagger type showing a woman whose physical dimensions seemed to defy natural human development. She stood beside a doorframe for scale, her head nearly touching the top of the frame at what must have been 6’3 in.

Her shoulders were so broad they appeared distorted in the image, and her arms showed muscular definition that Peton had never witnessed in any woman or in most men. The photograph subject was identified only by a number, specimen 41. And according to Ashford’s journal, she represented the culmination of an experiment that had consumed his family’s resources and moral boundaries for more than a quarter century. Dr.

Peton left Ravenswood estate that morning without examining any patient, carrying instead a burden of knowledge he hadn’t sought and couldn’t easily ignore.

He returned to his Charleston practice on Meeting Street, and tried to resume normal work, but the image of that woman, the calculations in that journal, the casual way Ashford had presented systematic human breeding as scientific achievement rather than moral abomination.

All of it lingered in his thoughts like a fever he couldn’t break. Pembbertton kept detailed personal diaries throughout his career, and his entries from April through June of 1843 reveal a man wrestling with what he’d witnessed.

He wrote about the conflict between his medical training, which taught him to view human bodies as subjects for scientific study and his religious beliefs, which insisted that human beings possessed inherent dignity that couldn’t be reduced to physical measurements.

He questioned whether he had any obligation to report what he’d seen, though to whom and under what authority remained unclear, since Ashford had broken no laws that Charleston’s courts would recognize.

The practice of breeding enslaved people for specific traits wasn’t illegal in South Carolina, wasn’t even particularly unusual, though most plantation owners conducted such programs with less systematic documentation, and certainly without inviting physicians to review their methods.

What made Ashford’s program distinctive wasn’t its cruelty, which was typical of slavery’s broader system, but its scientific approach and its spectacular success in achieving exactly what it set out to accomplish.

Peton’s diaries note that he’d encountered other breeding programs during his medical practice, had been called to plantations to assist with difficult births or treat injuries, and had witnessed how enslaved people were paired according to owners preferences rather than their own choices.

But Ashford’s program operated on a different scale entirely with three generations of careful selection producing results that seem to push the boundaries of normal human physical development.

The woman in the photograph, Specimen 41, was the program’s masterpiece, and Pembbertton couldn’t stop thinking about what her existence meant, what it revealed about the capacity for human cruelty when justified through scientific reasoning, and what it suggested about the enslaved people themselves who’d endured this systematic violation of their reproductive lives while somehow maintaining enough humanity to survive psychologically.

Peetton eventually made copies of certain pages from Ashford’s journal before returning the original, telling himself that documentation was a form of bearing witness, that even if he couldn’t stop what was happening, he could at least preserve evidence of what had been done.

Those copies survived in Pembbertton’s personal papers, which were donated to the South Carolina Historical Society after his death in 1878. The papers remained largely unexamined until 1962 when a graduate student researching antibbellum medical practices discovered them and recognized their significance. The copies included measurements, breeding pairings, and projections for future generations, but they also included something Peton added himself after visiting Ravenswood multiple times during the summer of 1843.

his own observations of specimen 41, whom he learned was called Ruth, by the people who lived with her in the quarters. Though official records used only her designation number, Peton’s observations paint a portrait that the measurements alone couldn’t capture. He described Ruth as possessing not just unusual size and strength, but an intelligence and awareness that made her constantly watchful, as if she understood exactly what she represented and what her existence meant within the broader system of slavery. He noted that

she spoke with careful precision, choosing words that revealed education beyond what most enslaved people received, suggesting someone had taught her to read and think critically, despite the enormous risks such education involved. He observed that other enslaved people at Ravenswood treated her with a complex mixture of respect, protectiveness, and something approaching reverence, as if her physical presence had become a symbol of resistance.

even when she engaged in no overt rebellious acts. Most significantly, Peton recorded that Ruth seemed to be preparing for something, though what exactly he couldn’t determine. She moved with deliberate purpose, observed everything around her with intense focus, and maintained what Peton described as controlled rage, barely concealed beneath a surface of compliance.

To understand Ruth’s story, to comprehend how a human being could be bred for specific traits across three generations and what psychological toll such a program inflicted requires understanding Charleston in the decades leading to 1843 and the particular form slavery took in the Carolina low country. Charleston had built its wealth on rice cultivation, transforming coastal marshlands into productive fields through a labor system that was arguably more brutal than cotton plantation slavery in the deep south. Rice cultivation required workers

to stand in flooded fields for hours, exposed to mosquitoes carrying malaria and yellow fever, their bodies bent under the Carolina sun while performing repetitive tasks that destroyed joints and muscles. The death rate among rice field workers was extraordinarily high with many surviving only a few years after being assigned to field labor.

This created constant demand for new workers and made plantation owners particularly interested in any methods that might produce workers who were stronger, more resistant to disease, and capable of sustained heavy labor. The Ashford family had arrived in South Carolina in 1768, part of the wave of wealthy English families seeking fortunes in colonial America.

They established themselves in Charleston’s merchant class initially trading in rice, indigo, and increasingly enslaved people brought from West Africa and the Caribbean. By 1790, they’d accumulated enough capital to purchase land north of Charleston and establish Ravenswood Plantation, named for the massive live oak trees draped with Spanish moss that gave the property an appearance of natural grandeur masking systematic brutality.

The plantation grew to encompass 2,000 acres of tidal marshland, transformed into rice fields, sustained by the labor of approximately 300 enslaved people who lived in wooden quarters that leaked during frequent rains and baked during summer months when Carolina humidity made breathing feel like drowning slowly.

Cornelius Ashford’s grandfather, William Ashford, had managed Ravenswood from 1790 until his death in 1815, operating it as a typical rice plantation with typical cruelty. But William’s son, Cornelius’s father, a man named Harrison Ashford, had different ambitions. Harrison had studied at the College of Charleston and developed interests that blended emerging scientific thinking with plantation management.

He’d read about animal breeding programs in England, studied agricultural journals discussing crop improvement through selective seed selection, and become fascinated by whether similar principles could be applied to human beings. This wasn’t original thinking. Plantation owners throughout the South had long practiced informal breeding, pairing enslaved people based on physical characteristics, and breaking apart families that didn’t produce desired results.

But Harrison wanted to approach it systematically to document everything to prove that human beings could be improved through careful genetic selection just like horses or cattle. Harrison began his breeding program in 1817, 2 years after inheriting Ravenswood. He started by surveying the entire enslaved population, measuring everyone, noting physical characteristics, tracking family relationships, and identifying individuals who possess traits he considered valuable.

He was particularly interested in height, muscular development, bone structure, and what he called constitutional vigor, meaning the ability to withstand disease and harsh conditions without succumbing. He created detailed records for each person, assigning them numbers rather than using the names they’d been given by their families or communities.

This numerical system was deliberate dehumanization, a way of transforming people into data points in an experiment that treated human reproduction as agricultural science. Harrison’s program operated through forced pairings. He would select two people based on their physical characteristics and order them to form partnerships, separating existing couples if they didn’t meet his criteria and punishing anyone who resisted.

Children born from these forced unions were evaluated constantly, measured starting in infancy, tracked through development, and either incorporated into future breeding plans if they showed desired traits or sold away to other plantations if they failed to meet expectations. The cruelty of this system compounded across years and generations.

Families were torn apart not once but repeatedly as children were sold or redistributed based on their physical development. Women were forced into partnerships with men they didn’t choose. Their reproductive lives controlled as completely as their labor. Men were evaluated like breeding stock valued for genetic contribution rather than any human qualities.

And all of this was documented in Harrison’s journals with clinical precision that treated systematic dehumanization as scientific progress. Harrison died in 1831, but not before establishing the foundations that his son Cornelius would expand. Harrison had identified several family lines within Ravenswood’s enslaved population that consistently produced children with desired physical traits, particularly unusual height and muscular development.

He documented these lines across two generations, creating what he believed was proof that human breeding could produce measurable improvements in strength and size. Cornelius inherited both the plantation and the obsession in 1831. He was 24 years old, recently graduated from South Carolina College, and determined to prove his father’s theories correct through even more rigorous methodology.

Cornelius expanded the breeding program significantly, hiring overseers specifically to help with documentation and monitoring. He created a classification system that ranked every enslaved person at Ravenswood according to their breeding value with the highest ranked individuals receiving better food rations and lighter work assignments to maximize their reproductive potential.

He developed projections for future generations, calculating how many years would be required to produce individuals with specific physical characteristics and planning breeding pairs decades in advance. His journals from this period read like agricultural breeding manuals, discussing genetic inheritance with the same language used for livestock improvement, as if the people he was manipulating were merely biological material rather than human beings with inner lives, emotions, and relationships. Among the family lines

Harrison had identified as most promising was one that traced back to a woman who’d been brought from Jamaica in 1800. The records identified her only as subject seven, though her descendants would later say her name was Abeni, a Yoruba name meaning we prayed for her arrival. A Beni stood 5′ 11 in tall, extraordinary for a woman of that era, and possessed unusual physical strength that made her valuable for heavy labor.

She’d been purchased specifically because of these characteristics brought from Jamaica, where breeding programs had operated longer than in mainland American colonies, creating populations of enslaved people who were systematically selected for size and strength across multiple generations. A Benny was paired with a man identified in records as subject 12, whose actual name was Samuel, who stood 6’4 in tall and had been born on a Virginia plantation before being sold to South Carolina. Their union was forced,

arranged by Harrison Ashford based solely on their physical characteristics without regard for their own preferences or feelings. A Benny gave birth to a daughter in 1818, a girl who would be designated subject 23 in the breeding records, but whom a Benny named Coutura, meaning incense or sacrifice.

Coutura inherited her mother’s height, reaching 6 ft by age 15, and showed the muscular development Harrison had hoped for. She became a centerpiece of his breeding program, monitored constantly, measured regularly, and eventually paired with another carefully selected man. When she reached what Harrison determined was optimal breeding age, Coutura was forced into partnership with a man designated subject 19, whose name was Daniel, who’d been born on Ravenswood and stood 6’2 in tall with shoulders that spanned 23 in

across. Daniel had been selected for the breeding program as a child, raised with extra rations to maximize his growth and trained for tasks that would develop his strength. He and Coutura produced a daughter in 1838, and this child would become Specimen 41, the woman whose photograph would eventually disturb Dr.

Peton so profoundly. The baby was born on a humid August morning, when Charleston’s heat made everything feel oppressive and heavy. The birth took place in a small wooden structure that served as Ravenswood’s birthing room, attended by an elderly midwife named Patients, who delivered hundreds of babies over four decades, and who’d learned to hide her sorrow at bringing children into a world where they would be owned and controlled from their first breath.

Coutura labored through the night and into morning, finally delivering just after dawn as light filtered through gaps in the wooden walls. The baby was unusually large, measuring 24 in long with a weight of 9 lb. Proportions that immediately signaled she was developing according to the genetic patterns Cornelius Ashford had spent years trying to cultivate.

Cornelius was notified immediately and arrived at the birthing room within an hour, accompanied by his chief overseer, a man named Edmund Vale, who kept detailed records for the breeding program. They measured the infant with the same clinical attention used for valuable livestock, recording dimensions, noting the proportional length of her limbs, examining her bone structure for signs of the robust development they’ projected based on her parents’ characteristics.

Cornelius assigned the baby her designation, specimen 41, marking her as the 41st child born into the breeding program since he’d taken control of Ravenswood. The number would follow her throughout her life, appearing in every record, every evaluation, every projection about her future use. Coutura wanted to name her daughter Ruth after a biblical figure who’d shown loyalty and courage in the face of exile and loss.

But that name never appeared in official plantation records. To Cornelius and his administrative apparatus, the baby was simply 41, a data point representing potential validation of theories about human breeding. The extra food rations began immediately. Cornelius ordered that Coutura receive portions of salt, pork, cornmeal, beans, and vegetables that exceeded standard allotments, ensuring optimal nutrition during nursing to maximize the infant’s early growth.

This created immediate tensions in the quarters where food was already scarce and distributed in carefully measured amounts designed to maintain work capacity without promoting health or strength beyond what benefited the plantation’s productivity. Some people resented the special treatment, seeing it as favoritism that came at their expense when the plantation’s overall food supply remained fixed.

Others understood that the extra rations were a poisoned gift, coming with expectations and control that would make Ruth’s life fundamentally different from normal enslavement’s already unbearable conditions. Patience. The midwife, who delivered Ruth, tried to help Coutura navigate the complicated social dynamics the extra rations created.

She advised discretion, suggested sharing portions with others to build community support rather than resentment, and warned that Ruth would face unique challenges as she grew. The child would need the community’s protection and solidarity, and alienating people through perceived privilege, even involuntary privilege imposed by owners, would make survival more difficult for both mother and daughter.

Coutura followed this advice as carefully as she could, maintaining relationships with other women in the quarters, sharing what extra food she dared, and trying to raise Ruth with some semblance of normal childhood, despite the constant surveillance that characterized every stage of the girl’s development. Ruth’s early years were defined by being constantly observed and measured.

Edmund Vale kept detailed journals documenting her growth and entries from 1838 through 1842 read like livestock breeding records noting every developmental milestone with clinical precision but no acknowledgement of human experience or emotion. Ruth at 3 months shows 15% greater muscle mass in limbs compared to average infants. Mother’s nutrition adequate.

Recommend maintaining enhanced rations. Ruth at 8 months demonstrates advanced motor control, pulling to standing position earlier than typical development timeline. Father’s height genetics apparently expressed, projecting adult height of 6’2 in to 6’4 in. Ruth at 12 months walking unassisted, showing grip strength approximately double that of average children her age.

recommend continued monitoring and enhanced nutrition through early childhood. Cornelius read these reports with deep satisfaction. Convinced that his breeding program was producing exactly the results, three generations of careful selection should yield, he began showing Ruth off to visitors, even when she was still a toddler, hosting gatherings where plantation owners from across South Carolina and neighboring states came specifically to observe her and hear about Ravenswood’s breeding program. These visits were torture for

Ruth as she grew old enough to understand what was happening. She would be brought out to stand before strange men who discussed her body as if she were livestock, evaluated her measurements against their own enslaved populations, and debated whether implementing similar programs on their plantations would yield sufficient returns to justify the investment.

Ruth learned from these exhibitions that she was not seen as fully human by the men who controlled every aspect of her life, and this knowledge shaped her understanding of the world. in ways that would have profound consequences years later. By age 5, Ruth stood 3 feet 11 in tall, significantly above average for her age with proportional muscular development that made her appear even more unusual.

Her arms and legs were longer than typical children’s proportions, giving her a gangly appearance that suggested she would eventually achieve the exceptional height Cornelius projected in his journals. Her body showed definition in the shoulder and back muscles that typically didn’t appear until adolescence, and her grip strength was remarkable enough that Veil documented her ability to hold weights that children twice her age struggled with.

But measurements didn’t capture Ruth’s psychological development, which was equally exceptional, though for reasons Cornelius never fully understood. Ruth absorbed everything around her with intense focus, learning to read situations and people’s moods with uncanny accuracy. She understood by age five that she was constantly being evaluated, that her body was property more valuable than most, and that this value made her both protected and trapped in ways other enslaved children weren’t. She learned to mask her

thoughts, presenting a blank face to white observers. While fury and awareness built inside her like pressure in a sealed container, she learned the dual consciousness required for survival, being who she needed to be for those who owned her while preserving some inner self that remained separate from their control.

Coutura taught Ruth as much as she could about their family history, about a Benny who’d been Ruth’s grandmother, about the fact that their unusual size and strength came from West African heritage where women had been tall and powerful before being captured and commodified. These conversations gave Ruth a framework for understanding herself that differed radically from Cornelius Ashford’s narrative of successful breeding.

Where Cornelia saw genetic improvement through selective pairing, Coutura taught Ruth to see inherited strength from ancestors who’d been free, characteristics that belonged to her rather than being created by the Ashford’s program. Patience also played a crucial role in Ruth’s early development. The elderly midwife had delivered Ruth, had watched her grow, and had recognized early that this child possessed not just physical exceptionality, but intelligence and awareness that would make her either a leader or a martyr, depending on how

circumstances unfolded. Patience taught Ruth about Charleston’s history of slave resistance, about Denmark V’s planned uprising in 1822 that had been betrayed before it could begin, about the constant undercurrent of rebellion that existed even when it couldn’t be expressed openly. She taught Ruth to be patient, to survive, to wait for opportunities rather than acting from anger in ways that would get her killed without achieving anything meaningful.

By age seven, Ruth was put to work at tasks specifically designed to build her physical capabilities further. She carried loads of rice from fields to processing areas, developing her back and leg muscles. She lifted heavy barrels, building upper body strength. She performed labor that would typically be assigned to adolescent boys, and she managed it adequately despite her young age.

Cornelius watched this progress with pride that bordered on obsession, documenting every achievement as further evidence that his breeding program could produce superior workers who would ultimately generate enormous profits through both their labor and their value in breeding future generations. The quarters at Ravenswood had developed their own distinct culture over decades, maintaining elements of West African traditions that had survived the Middle Passage and slavery’s attempts to erase cultural identity.

People spoke gula, a creole language, blending English with African linguistic patterns that allowed conversations white observers couldn’t fully understand. They cooked traditional foods when possible, maintained spiritual practices that incorporated African beliefs, and created tight-knit communities that provided emotional support in a world designed to break their spirits.

Ruth grew up embedded in this culture, learning its codes and patterns, understanding how resistance operated through subtle acts that flew beneath overseers notice. She learned which songs carried coded messages, how information moved through seemingly casual conversations, and which people could be trusted with dangerous knowledge.

This education prepared her for roles she couldn’t yet imagine, but would eventually need to fill. Among the enslaved population at Ravenswood were natural leaders who commanded respect through wisdom, courage, or spiritual authority. One such person was a man named Gabriel, 48 years old in 1843, who’d been born in Charleston and survived conditions that had killed many others.

Gabriel worked as a blacksmith, a skilled position that gave him slightly more autonomy than field workers received, and he used that position to maintain awareness of everything happening on the plantation and in Charleston beyond. Gabriel had connections throughout the city’s enslaved community, relationships built over decades that allowed information to flow between plantations and urban households.

He knew which ship captains might be sympathetic to fugitives, which white abolitionists existed in Charleston despite the risk such beliefs created, and which routes through the Low Country offered the best chances for successful escape. More importantly, Gabriel understood how to read the political and social currents that shaped slavery’s evolution.

And by 1843, he was increasingly convinced that significant changes were approaching, though what form those changes would take remained uncertain. Gabriel watched Ruth’s development with particular attention. He saw in her not just exceptional physical capabilities, but potential for leadership that could be channeled productively if circumstances allowed.

He began teaching Ruth things that went far beyond what Cornelius’s program intended, subtle lessons about power and resistance, disguised as ordinary conversations. He taught her about leverage, both literal and metaphorical, about how strength could be applied efficiently rather than wastefully. About how understanding systems allowed you to find their vulnerabilities.

He taught her to think strategically, to evaluate long-term consequences rather than acting impulsively, and to recognize that sometimes the most powerful resistance looked like patience and preparation rather than direct confrontation. By age 10, Ruth had internalized these lessons alongside Cornelius’s constant measurements and evaluations.

She performed her assigned labor without visible resistance, submitted to Vale’s documentation without complaint, and maintained a facade of compliance that masked growing awareness and carefully controlled rage. But privately she was preparing for something, though what exactly even she couldn’t fully articulate yet.

She watched everything, remembered everything, and waited for circumstances that might create opportunities for action. Ruth’s measurements at age 10 documented systematic physical development that exceeded even Cornelius’s optimistic projections. She stood 5’5 in tall with measurements that approached those of adult women.

Her chest measured 36 in around, her arms measured 13 in in circumference, and her shoulders spanned 20 in across. She could lift loads that grown men struggled with, and Cornelius documented these achievements with satisfaction that completely ignored Ruth’s humanity or psychological experience. He’d begun showing her off more frequently to visiting plantation owners, and these exhibitions became regular events where Ruth was made to demonstrate her strength by lifting heavy objects, carrying multiple rice sacks simultaneously, and performing

feats that amazed observers who’d never witnessed such capabilities in any woman, or even in most men. The visitors reactions ranged from impressed to skeptical to disturbed, but most saw potential financial applications if Ravenswood’s breeding program principles could be replicated on their own properties.

Cornelius encouraged this interest, sharing his methods openly and discussing how coordinated breeding programs across multiple plantations could produce an enhanced population of workers who would be more productive and therefore more profitable. He envisioned a future where plantation owners throughout the south participated in systematic breeding networks, sharing information and selectively trading individuals to maximize desired traits across regions.

The years between 1840 and 1843 marked Ruth’s transformation from a physically precocious child into an adolescent whose development continued exceeding projections. By age 13, she’d reached 5′ 11 in in height, matching her grandmother, A Benny’s unusual stature and approaching what would eventually be her full adult height.

Her body showed muscular definition that was extraordinary for any adolescent and virtually unprecedented in young women. Her measurements during this period documented development that Vale described in his journals as representing the breeding program’s successful culmination. Ruth’s chest measured 42 in around at age 13.

Her arms measured 16 in in circumference. Her shoulders spanned 22 in across and her thighs measured 26 in around. These numbers appeared constantly in Veil’s documentation, always accompanied by observations about work capacity, physical capabilities, and breeding potential that treated Ruth as valuable property rather than a human being with thoughts, feelings, and awareness of what was being done to her.

But numbers couldn’t capture what it meant to inhabit Ruth’s body and mind during these years. She understood by now that her physical capabilities were precisely what made her valuable and therefore imprisoned. She was too important to Cornelius’s validation of his life’s work to ever be free through conventional means.

She recognized that Cornelius had already begun planning her reproductive future, identifying male children in the breeding program who would be appropriate matches when they reached maturity, treating her future children as already predetermined elements in his multigenerational experiment. Ruth was aware of these plans because information moved through the quarters in sophisticated ways that white observers never fully understood.

Household staff overheard conversations in the main house and shared them. Field workers noticed which young men received extra attention from overseers who were evaluating them for future breeding decisions. People pieced together the larger picture from fragments of information and passed it along through networks built on trust and survival.

Ruth knew exactly what Cornelius intended for her, and the knowledge sat inside her like poison, corroding any possibility of hope or future that she might have tried to maintain. During this period, Ruth was assigned to work in Ravenswood’s rice mill, a massive structure where harvested rice was processed through steps that required constant heavy lifting.

Workers carried 60 lb sacks from storage areas to processing stations, lifted sacks onto tables for sorting, then carried processed rice to wagons for transport to Charleston’s docks. The work was brutal. Performed in heat that regularly exceeded 100° with humidity that made breathing difficult and dust from rice hulls that filled the air, causing lung problems for people who worked there for extended periods.

Ruth worked alongside grown men, many of them selected for mill work specifically because of their size and strength. She outperformed most of them, carrying heavier loads, working longer hours without apparent fatigue, maintaining pace that left others exhausted. The men had complex reactions to this.

Some respected her abilities and treated her as an equal. Others felt threatened or diminished. Most understood that her strength was both impressive and tragic, evidence of what systematic human breeding could accomplish when people were treated as livestock rather than human beings. Cornelius used Ruth’s performance in the rice mill as evidence for his theories, bringing visitors specifically to observe her working.

He would stand at a distance with plantation owners from Georgia, North Carolina, and deeper south states, pointing out how she handled loads requiring two men to lift normally, how she maintained pace throughout 12-hour shifts, how she showed no signs of the health deterioration that affected other mill workers within months of assignment.

These demonstrations were exhibitions disguised as normal work, and Ruth understood that every moment of her labor was being evaluated, documented, and transformed into evidence for Cornelius’s theories about human breeding. One visitor during the autumn of 1842 was particularly significant. a Virginia plantation owner named Thomas Hrix, who operated a tobacco operation near Richmond and had traveled to Charleston specifically to evaluate whether Ravenswood’s breeding program claims were legitimate. Hris spent 5

days at the plantation, examined Vale’s journals extensively, interviewed Cornelius about methodology, and observed Ruth working in the mill for extended periods. He was deeply impressed by what he witnessed and saw Ruth as proof that human beings could indeed be selectively bred for desired characteristics with the same success achieved in horse or cattle breeding.

On the final evening of Hrix’s visit, he made Cornelius an extraordinary proposal. He would purchase Ruth for $4,000, an enormous sum that reflected both her demonstrated capabilities and her potential for breeding the next generation of enhanced workers. Hrix explained his vision with enthusiasm that revealed how thoroughly he’d embraced the concept of systematic human breeding.

He would pair Ruth with the strongest male workers on his Virginia plantation, monitor resulting children with the same careful documentation Cornelius had maintained, and potentially develop his own line of specially bred workers that would make his tobacco operation the most productive in the region. He spoke about Ruth as if she were a prize mayor whose bloodline would improve his stock, using language that completely erased her humanity while celebrating her physical capabilities.

Cornelius’s initial reaction was conflicted. Ruth represented 15 years of careful work, the culmination of his father’s theories and his own refinements to the breeding program. Selling her would mean abandoning the program’s continuation at Ravenswood, or starting over with younger subjects, who would require decades to develop comparable characteristics.

But $4,000 was an enormous sum, more money than Cornelius had ever been offered for any enslaved person, and it represented liquid capital that could be invested in expanding Ravenswood’s operations or purchasing additional land and workers. Cornelius asked Hrix for time to consider the offer, and Hrix agreed, returning to Virginia with the understanding that Cornelius would send word within 6 weeks about whether he accepted.

The potential sale became known throughout Ravenswood’s quarters within hours of Hrix’s departure. Information passing through the networks that connected household staff who’d overheard the negotiations with field workers and everyone else who lived under Cornelius’s control. The news spread in whispers, passed from person to person until everyone knew that Ruth might be sold away from South Carolina, separated from her mother and grandmother, from the community that had raised her, sent to Virginia to become the foundation of another man’s breeding

program in a place where she would know no one and have no allies. The reaction in the quarters was mixed and complex. Some saw the sale as potentially positive for Ruth, reasoning that Virginia was further from Cornelius’s direct control, and perhaps she would find opportunities to escape or resist that weren’t possible at Ravenswood.

Others understood that the sale would simply transfer her to different ownership with no guarantee of better conditions, and the certainty of losing every human connection she’d built over 15 years. A few argued that resisting the sale was impossible, that Cornelius owned Ruth completely, and could do whatever he wanted, regardless of anyone’s preferences or feelings.

For Ruth herself, learning about the potential sale, created a crisis that forced decisions she’d been avoiding through years of careful compliance. She spent a sleepless night after hearing the news, lying in the small quarters she shared with her mother, staring at wooden ceiling beams and trying to understand what options existed, if any.

The thought of being torn away from Coutura, from patients who delivered her and taught her to survive, from Gabriel who’d given her frameworks for understanding power and resistance, from everyone who knew her history and cared about her beyond her breeding value, created desperation unlike anything she’d experienced before.

She’d endured 15 years of systematic dehumanization by holding on to connections with family and community by maintaining relationships that reminded her she was a person rather than merely specimen 41 in Cornelius’s journals. The prospect of losing those connections, of being isolated in Virginia, with no one who understood her past or saw her as fully human, made the future seem unbearable in ways that even the breeding program’s daily humiliations hadn’t achieved.

Ruth went to find Gabriel the following morning, waiting until her work assignment in the mill provided opportunities to move around the property with some freedom. Gabriel worked in the blacksmith shop, a separate building near the main complex where he repaired tools and equipment that kept Ravenswood’s operations functioning.

Ruth approached during a moment when no overseers were nearby, and Gabriel immediately recognized the urgency in her expression. She told him about the potential sale, about Hrix’s offer, and Cornelius’s consideration of it, about her desperation at the thought of being sent to Virginia. Gabriel listened without interrupting, his weathered face showing concern that went beyond sympathy to encompass strategic thinking about what possibilities existed in an impossible situation.

When Ruth finished speaking, Gabriel was quiet for a long moment, his hands continuing to work on the plow blade he was repairing, while his mind clearly engaged with more complicated problems. Finally, he spoke in a low voice that couldn’t be overheard beyond a few feet. You’re stronger than any man on this plantation, stronger than most men anywhere.

They’ve spent 15 years building that strength, thinking it makes you more valuable to them. But strength can serve different purposes than the ones they intended. You understand what I’m saying? Ruth understood exactly what he was saying, though the implications terrified her as much as they excited her. Gabriel was suggesting that her physical capabilities developed through Cornelius’s breeding program to make her a more productive worker and valuable breeding stock could be weaponized for resistance.

That the same strength that made her impossible to sell to anyone who feared rebellion could be used to prevent the sale through direct action rather than passive acceptance. Gabriel continued speaking, his voice remaining carefully quiet. I’m not telling you what to do. This is your life, your decision. But I’m telling you that if you decide you won’t accept being sold, there are people here who would support you.

Not everyone, not even most people because the risks are enormous and most folks have families they’re trying to protect, but some would help if you needed it. And you should know that Charleston’s got networks you don’t see, connections between plantations and the city, people who might provide aid if circumstances created opportunities. Ruth absorbed this information, understanding that Gabriel was offering more than just emotional support.

He was suggesting that organized resistance might be possible, that she wasn’t completely alone in facing impossible choices, and that the community she’d grown up in contained resources and relationships she hadn’t fully recognized. She asked him what kind of help might be available, and Gabriel’s answer was careful, but substantive.

There were people in Charleston’s free black community who maintained connections with enslaved populations, passing information about escape routes and sympathetic ship captains. There were white abolitionists, rare in South Carolina but present, who might provide assistance under certain circumstances. Most importantly, there were enslaved people throughout the Low Country who understood that resistance required coordination and timing, who’d been waiting for opportunities or catalysts that might make collective action

possible rather than individually suicidal. Gabriel told Ruth that if she decided to resist the sale, the first step would be gathering people willing to help create disruption that would make the transfer to Hrix difficult or impossible. sabotage of plantation operations, minor at first to avoid immediate suspicion, escalating if necessary, to create chaos that would distract overseers and potentially create opportunities for escape during the confusion.

He emphasized that such actions would be extraordinarily dangerous, that discovery would result in severe punishment, including death, and that even success wouldn’t guarantee freedom, since they lived in a slave state surrounded by other slave states, with hundreds of miles separating them from free territory in the north. Ruth listened to all of this, feeling the weight of decisions that would determine not just her future, but potentially the futures of others who might choose to support her.

She told Gabriel she needed time to think, and he nodded, understanding that this wasn’t a choice to make impulsively. But as Ruth left the blacksmith shop and returned to the mill, she realized that part of her had already decided she would not accept being sold to Thomas Hrix. She would rather die fighting than be transported to Virginia to become the foundation of another breeding program that would consume her children and grandchildren the way Cornelius’s program had consumed her life.

Over the following two weeks, Ruth began preparing for possibilities she couldn’t fully articulate yet. She started training others in the same way Gabriel had taught her, sharing techniques for building strength and endurance through exercises that could be performed before dawn or after work assignments ended. She presented this training as practical methods for making brutal labor slightly more bearable.

But her real purpose was creating a core group of people who would be physically capable of coordinated resistance if opportunities arose. She gathered small groups, never more than four or five people at once to avoid suspicion, teaching them how to lift heavy objects efficiently, how to develop the muscles used in fighting or running, how to increase stamina through sustained effort.

Some participants understood immediately what Ruth was really preparing them for and committed themselves fully. Others participated more cautiously, willing to build strength, but uncertain whether they could actually engage in open resistance when the moment came. A few refused entirely, too frightened of consequences, or too convinced that resistance was futile against a system backed by overwhelming force and legal authority.

Among those who committed most fully was a young man named Isaac, 19 years old, who’d been born at Ravenswood, and worked as a field hand in the rice patties. Isaac had been identified as a potential breeding program participant by Vale, marked for future pairing with carefully selected women once he reached what Cornelius considered optimal breeding age.

Isaac understood that his future under the breeding program would involve the same loss of reproductive autonomy that Ruth faced. And this knowledge made him willing to take risks that others avoided. Isaac became Ruth’s closest ally during this period of preparation, helping recruit others for the training sessions, providing strategic thinking about how resistance might work if it came to that, and offering emotional support to Ruth as she navigated the psychological burden of planning something that could result in multiple

deaths, including her own. Another key ally was a woman named Hannah, 26 years old, who worked in Ravenswood’s main house as a cook andress. Hannah’s position gave her access to information that field workers never heard directly. She could listen to conversations between Cornelius and his wife Margaret, observe documents left visible in Cornelius’s study, and notice patterns in how the Asheford household operated.

She passed this information to Ruth whenever opportunities arose, creating an intelligence network that helped Ruth understand exactly what was being planned regarding her potential sale and what vulnerabilities might exist in Ravenswood’s security. Through Hannah, Ruth learned critical details about the sale negotiations that weren’t common knowledge.

Thomas Hendrickx had paid $1,000 as a deposit with the remaining $3,000 to be paid upon Ruth’s delivery to Virginia. Cornelius had hired professional slave catchers to transport Ruth. Men known for brutal efficiency in preventing escape attempts during transfers between states. The transport was scheduled for December 15th, 1842, giving Cornelius time to complete the rice harvest and maximize profit before losing Ruth’s labor.

Ruth also learned something that changed her entire understanding of what was at stake. Through Hannah’s observations, Ruth discovered that Cornelius kept additional records beyond Veil’s journals, documents stored in a locked cabinet in his study that detailed the full scope of the breeding program across three generations. These records included information about families that had been separated, about children who’d been sold when they failed to develop, according to projections, and about Cornelius’s plans for expanding the program through

networks with other plantation owners across multiple states. Ruth became obsessed with seeing those records, with understanding the complete truth of what had been done to her family and countless others. But accessing Cornelius’s study was extraordinarily dangerous. The main house was off limits to field workers, and any enslaved person found there without legitimate reason would face immediate punishment.

Hannah explained that the study’s window could potentially be opened from outside, that Cornelius and Margaret often attended social gatherings in Charleston that left the main house less supervised, and that with proper timing and lookouts, someone might be able to access the study briefly. The risks were enormous, but Ruth decided they were necessary.

She needed to see those records, needed to understand the full scope of what she was part of, needed documentation that could serve as evidence if opportunities ever arose to tell the story of what had been done. Ruth, Isaac, Hannah, and two others began planning the attempt with careful attention to timing and coordination. They chose November 20th for the action, a date when Cornelius and Margaret were scheduled to attend a dinner party at a neighboring plantation, an event that would keep them away from Ravenswood for at least 5 hours. The plan required

Hannah to ensure the study window remained unlocked during her cleaning duties. Isaac and another field worker to serve as lookouts, watching for any unexpected returns or patrol routes that might bring overseers near the main house, and Ruth to actually enter the study and examine whatever documents she could find in the limited time available.

The evening of November 20th arrived with typical low country weather, cool and damp, with fog rolling in from the coastal marshes. Cornelius and Margaret departed for their social engagement in mid-afternoon, traveling by carriage with two household attendants. Ruth waited until full darkness, then made her way to the main house with a caution that seemed excessive given her size, but which Gabriel had taught her was essential for successful stealth.

Isaac was positioned where he could watch the main road, leading to Ravenswood’s entrance. Hannah remained in the main house’s kitchen, where her presence wouldn’t raise suspicion. Ruth approached the study window, which Hannah had left unlocked as planned, and carefully opened it enough to climb through. The study was dark except for moonlight filtering through windows, providing just enough illumination to see shapes and outlines.

Ruth waited for her eyes to adjust fully, then began searching for the locked cabinet Hannah had described. She found it against the eastern wall, a substantial piece of furniture made from mahogany with brass fittings and a lock that looked more serious than anything protecting most plantation records.

Ruth had anticipated this problem and brought tools Gabriel had provided, thin pieces of metal that could potentially manipulate simple lock mechanisms. She worked carefully, trying to remain quiet while applying pressure that might release the lock’s catch. After nearly 15 minutes of careful manipulation, feeling growing panic about the time passing, the lock finally clicked open.

Ruth pulled the cabinet doors open and found exactly what Hannah had described. Multiple leatherbound volumes containing Cornelius’s detailed records of the breeding program. Ruth couldn’t read all of them in the limited time available, so she focused on the most recent volume, the one covering 1830 through the present.

She read by moonlight, her hands shaking as she absorbed information that exceeded her worst expectations. The volume documented her own development in exhaustive detail. Every measurement, every projection about her future breeding potential, every plan for her children, who didn’t yet exist, but whom Cornelius had already designated for roles in the program’s continuation.

But more disturbing than information about herself was what Ruth discovered about others. The volume contained references to dozens of children who’d been born into the breeding program over the past 13 years. Some had been sold to other plantations when they failed to develop desired characteristics. Others had died from illness or accidents that the record suggested might have been negligence or worse when their development disappointed Cornelius.

Ruth found names and numbers, brief notations that represented human lives treated as experimental failures, families deliberately separated to make room for next attempts at achieving desired traits. She found documentation of forced pairings of women who’d been punished for refusing to comply with breeding assignments, of men who’d been sold away when their children didn’t meet expectations.

The scope was breathtaking and horrifying. a systematic program of human breeding that had consumed countless lives while producing a handful of individuals like Ruth, who met Cornelius’s criteria for success. Ruth discovered that she had siblings she’d never known existed, half siblings from her mother’s previous forced partnerships before being paired with Daniel.

Two children, both sold to plantations in Georgia, when they failed to show the height and strength Cornelius projected based on their parents’ characteristics. Their names were in the records along with their sale prices and the plantations that had purchased them, information that Ruth committed to memory, even as tears blurred her vision.

Most disturbingly, Ruth found Cornelius’s projections for future generations, plans that extended decades into the future and involved coordination with plantation owners across multiple states. Cornelius had negotiated with Thomas Hrix about purchasing back any children Ruth produced in Virginia, bringing them to South Carolina to continue the breeding line.

He’d made similar arrangements with plantation owners in Georgia and North Carolina, creating a network where children from the breeding program would be distributed across properties, then selectively reunited for breeding as adults to maintain and enhance desired genetic traits. The vision was comprehensive and chilling, transforming slavery from merely an economic institution into a coordinated program of human breeding that would span regions and generations.

Cornelius had calculated that enslaved people bred for specific traits could be sold for triple normal prices, creating massive profits that would incentivize other plantation owners to participate in the network. The financial projections were detailed, showing expected returns over 20-year periods, comparing investment costs against anticipated revenue from selling enhanced workers to other plantations.

Ruth read all of this with growing rage that clarified her understanding of what was at stake. She’d known the breeding program was cruel. But discovering the full scope, the casual destruction of families, the cold calculation behind every forced pregnancy, the vision of expanding this system across the entire South, transformed her understanding of what needed to be opposed.

She carefully removed specific pages from the volume, documents that detailed the breeding program’s history and Cornelius’s future plans. She wanted evidence, wanted documentation that could potentially prove what had been done, even if she didn’t survive to tell the story herself. She folded the pages and tucked them inside her clothing, then replaced the volume in the cabinet and tried to make the lock appear undisturbed.

But as Ruth prepared to leave through the window, she heard voices outside the main house. Cornelius and Margaret returning far earlier than expected from their social engagement. Ruth had perhaps seconds to decide what to do. Attempting to exit through the window would likely result in being seen. Hiding inside the study meant being trapped if Cornelius entered the room.

Neither option was good, but hiding offered slightly better chances than being caught climbing out a window in full view. Ruth squeezed herself behind a tall bookshelf in the study’s corner where shadows were deepest, pressing against the wall and trying to control her breathing. She heard Cornelius and Margaret enter the main house, heard their voices as they moved through the first floor, heard Margaret complaining about the dinner party being cancelled due to illness in the host family.

Ruth’s heart was pounding so violently she feared it would somehow give her away, and the stolen documents pressed against her body felt impossibly obvious. Cornelius and Margaret remained on the first floor for what felt like hours but was probably only 20 minutes discussing plantation business and social matters while Ruth remained frozen behind the bookshelf.

Finally, they retired upstairs to their bedroom and the main floor became quiet. But Ruth couldn’t leave immediately without risk of encountering household staff who might still be working. She remained hidden for another hour, muscles cramping from maintaining the same position. fear creating a constant state of alert that exhausted her mentally even while her body remained motionless.

Finally, well past midnight, the house became truly quiet. Ruth carefully emerged from behind the bookshelf, moved to the window, and climbed out as silently as possible. Isaac was still at his lookout position, nearly frantic with worry about Ruth’s prolonged absence. She signaled that she was safe, and they both made their way back to the quarters through fog that had grown thicker, providing cover, but also making navigation more difficult.

Over the following 3 days, Ruth shared what she’d discovered with the small group she’d been training. She showed them the documents she’d taken, explained the scope of Cornelius’s breeding program, and his vision for expanding it through coordination with other plantation owners. The reaction was horror, rage, and for some, a kind of grim vindication.

They’d known the system was evil, but having documentary evidence of systematic human breeding, of families deliberately destroyed across generations, of future plans to expand the program across multiple states, made the evil undeniable and immediate. But possessing this knowledge created a crisis of action. What could they do with this information? They were enslaved people with no legal rights, no access to courts or authorities who would care about their testimony, no way to expose Cornelius’s program through official channels. The only authorities

they could potentially reach were other plantation owners who likely shared Cornelius’s views or northern abolitionists who were too distant to provide immediate help and whose intervention would probably arrive too late to prevent Ruth’s sail to Virginia. Ruth argued that they had to do more than just possess knowledge.

They had to act in ways that would disrupt the sale, prevent her transfer to Virginia, and ideally create enough chaos to escape entirely. But escape where? South Carolina was surrounded by slave states, and reaching free northern states required traveling hundreds of miles through hostile territory where slave patrols operated, and any black person without papers would be assumed to be a fugitive, subject to immediate capture.

The debate among the group lasted two days with people arguing different positions passionately. Some wanted to attempt immediate escape before the scheduled December 15th sale. Others thought escape was impossible and preferred sabotaging Ravenswood’s operations to hurt Cornelius financially.

A few were so frightened of consequences that they wanted to abandon the entire plan and hoped that Ruth’s situation in Virginia might somehow be better than they feared. Ruth listened to all perspectives, then made her position clear with a directness that left no room for misunderstanding. She would not be sold to Thomas Hrix and transported to Virginia to become the foundation of another breeding program.

She would rather die fighting than submit to that future. If others wanted to join her in resistance, she welcomed their help and would do everything possible to protect them. But she understood the risks were enormous and didn’t judge anyone who chose survival over resistance. She would act regardless of whether others joined her.

Her willingness to die fighting rather than accept being sold changed the dynamic of the discussion. Several people who’d been hesitant committed themselves, inspired by Ruth’s resolve or shamed by their own fear, and the core group solidified around 13 people willing to take coordinated action. They spent the next week developing plans that balanced the desire for comprehensive disruption against the need to avoid early discovery that would trigger immediate response before they were ready. The plan they created was

multi-layered and designed to create maximum chaos across multiple fronts simultaneously. They would sabotage critical plantation equipment in ways that appeared accidental. Start small fires in outlying fields that would require attention without threatening the main complex. Damage rice processing machinery to prevent normal operations and create an atmosphere of escalating disaster that would distract overseers and create confusion that might provide opportunities for escape during the chaos. The timing was crucial. They

would begin the sabotage on December 1st, 2 weeks before Ruth’s scheduled departure, giving them time to create cumulative disruption while Ruth remained on the plantation where she could coordinate response to changing circumstances. If successful, they hoped to create enough chaos that Hrix would reconsider the purchase, fearing that Ruth had become a liability rather than an asset.

At minimum, they hoped to delay the transfer long enough to explore other options, including potential escape routes Gabriel had mentioned through Charleston’s networks. But Ruth had an additional objective beyond preventing the sale or escaping. She wanted Cornelius to understand that he’d created something he couldn’t control.

That the breeding program hadn’t just produced physical strength, but had cultivated intelligence, awareness, and capacity for coordinated resistance. She wanted him to see that treating human beings as livestock to be improved through selective breeding created consequences he hadn’t anticipated. that reducing people to measurements and numbers in journals didn’t actually eliminate their humanity or their ability to resist the system that oppressed them.

The sabotage began on December 1st with small incidents that could plausibly be attributed to coincidence or carelessness. A plow broke during fieldwork when a deliberately weakened handle snapped. An ax head flew off its mount, nearly injuring an overseer. A wagon wheel shattered under load, spilling rice and creating delays in transport schedules.

Each incident by itself was unremarkable, the kind of minor problem that occurred regularly on any plantation. But the frequency and timing suggested either extreme bad luck or something more deliberate. Edmund Vale noticed the pattern immediately and increased surveillance of the quarters, watching for signs of organized resistance.

But he couldn’t prove intentional sabotage when everything could be explained as equipment failure or worker negligence. Cornelius became increasingly agitated as problems mounted. The rice harvest was being delayed, costing him money and potentially affecting his reputation among Charleston’s planter elite. Thomas Hrix sent a letter questioning whether the sale should proceed, expressing concern that if conditions at Ravenswood were deteriorating, perhaps Ruth’s value was affected by whatever problems plagued the plantation’s operations. The

mounting pressure intensified Cornelius’s response. He increased work hours, reduced already inadequate food rations as punishment for perceived carelessness, and authorized overseers to use more severe discipline for any infractions, regardless of how minor. He intended this increased severity to restore order, but it had the opposite effect.

People who’d been hesitant to support Ruth’s resistance saw no path to improved conditions through compliance, and the base of support for coordinated action expanded. On December 8th, one week before Ruth’s scheduled departure, the situation escalated dramatically when the rice mill suffered catastrophic structural failure.

A support beam that had been carefully weakened over several days through strategic cuts that appeared as natural wood rot finally collapsed during operation, falling across machinery and destroying mechanisms that would require weeks to repair. No one was killed, but several workers suffered injuries serious enough to prevent them from working, further reducing Ravenswood’s operational capacity at the worst possible time.

That same evening, fire broke out in one of Ravenswood’s storage barns, destroying equipment and supplies worth thousands of dollars. The fire appeared to start from a lantern positioned too close to hay bales, a plausible accident, but its timing, combined with the mill collapse, made Vale certain that deliberate sabotage was occurring on a scale that threatened Ravenswood’s entire operation.

Cornelius called an emergency meeting with his overseers that evening, and Hannah overheard enough of the discussion to understand that new security measures were being implemented immediately. Increased patrols of the quarters at night, restrictions on movement between different areas of the plantation, enhanced surveillance of anyone who’d been near the sites where incidents occurred, and authorization for overseers to use whatever force they deemed necessary to maintain control and prevent further sabotage.

These new security measures threatened the planned resistance significantly. Ruth gathered her group that night in darkness between the quarters and the treeine, keeping their voices low while debating whether to abandon the plan or accelerate it before Cornelius’s enhanced security made action impossible. Isaac argued for immediate escalation, reasoning that they’d already disrupted operations enough to make Cornelius suspicious, and waiting would only give him time to identify participants and take preventive action. Others

disagreed, saying that accelerating meant abandoning careful planning for desperate improvisation that would almost certainly fail and result in everyone being killed or sold away to destinations where they’d face even worse conditions than they endured at Ravenswood. The debate became heated with fear and frustration emerging in raised voices that threatened to draw attention from the new patrols Vale had implemented.

Ruth let people argue for several minutes, understanding that everyone needed to express the terror they felt about what they were contemplating. Then she made a decision that balanced preparation against the rapidly closing window of opportunity. They would act on December 13th, 2 days before her scheduled transfer to Virginia.

That gave them time to finalize details while Cornelius’s security was still being organized and implemented. It was their best compromise between preparation and the need for immediate action before circumstances made resistance completely impossible. When the meeting ended, 13 people had committed to attempting escape if opportunities arose during the planned chaos.

27 others said they would participate in creating diversions but wouldn’t flee because they had young children or elderly family members they couldn’t abandon or because they were simply too frightened of the consequences that would follow discovery. Ruth thanked everyone for their courage. Understanding that even those who chose not to run were taking enormous risks by supporting the disruption.

She also understood that this might be the last time she saw many of these people, that the plan they developed had realistic chances of ending with multiple deaths, including her own. Over the next 3 days, Ruth moved through her assignments with unusual focus, aware that these might be her final days at Ravenswood. She memorized details of the landscape, noting the positions of overseers during different times of day, observing patterns in the new patrol schedules Vale had implemented, identifying the best routes toward Charleston if escape

became possible. She was preparing for the night of December 13th with the same methodical attention Cornelius had applied to measuring her development for 15 years, except now that attention served her purposes rather than his. She also took time to speak privately with her mother Ketura and her grandmother Abeni, who was now elderly and frail, but still possessed the fierce dignity that had sustained her through more than four decades of enslavement.

Ruth told them what she was planning, not in specific detail, but enough that they understood she was preparing to resist her sail to Virginia through actions that might result in her death. Coutura wept, holding Ruth and expressing the helpless fury of a mother, watching her child face impossible choices in a system designed to destroy families.

A Bainy didn’t weep, but spoke with a intensity that made every word feel like a blessing and a command. You carry our strength. Your grandmother’s grandmother was tall like you, strong like you, free like we were meant to be. They tried to breed us like animals, but they just concentrated what we already had.

That strength is yours, not theirs. Use it however you need to. We’ll be proud of you regardless of what happens. December 13th arrived with weather that seemed to reflect the tension building at Ravenswood. Storm clouds gathered over the low country throughout the day, bringing wind that rattled shutters and bent trees, creating an atmosphere of impending violence that matched what Ruth and her allies were preparing to unleash.

Ruth worked her assigned shift in the rice mill, performing her tasks with the same efficiency she’d maintained for years, while internally preparing for evening’s planned actions. As darkness fell, the storm intensified, bringing rain that fell in heavy sheets and lightning that illuminated the plantation in brief stark flashes. Ruth waited in the quarters until after midnight, when most people had gone to sleep despite the storm’s noise.

Then she moved through the darkness, touching doors in pre-arranged signals. 13 people emerged, all dressed in dark clothing, carrying small bundles of food and supplies they’d managed to gather without raising suspicion. Ruth led them toward the coastal route Gabriel had identified as offering the best chance of reaching Charleston’s waterfront, where sympathetic ship captains might potentially provide passage further north.

They’d covered perhaps 300 yards, moving between buildings and using the storm’s noise to mask their movement when a shout rang out behind them. A patrol had spotted the group despite the darkness and rain, recognizing that a large number of people moving together at night represented exactly the kind of coordinated action Vale had warned everyone to watch for.

What happened next occurred with shocking speed. Ruth had known discovery was likely and had prepared mentally for confrontation. When the overseer approached, ordering them to stop and raising his rifle, Ruth didn’t comply with the command. Instead, she did something that 15 years of controlled rage and cultivated strength had prepared her for. She attacked.

Her first strike broke the overseer’s arm with force that made bones snap audibly, even over the storm’s noise. Her second blow threw him to the ground with impact that drove air from his lungs and lightly cracked ribs. She moved with efficiency, born from years of lifting heavy loads and understanding exactly how to generate and apply force.

The other two overseers present hesitated in shock, never having witnessed an enslaved person engage in direct violent resistance, certainly never having seen a woman attack with such devastating effectiveness. That momentary hesitation cost them. Isaac and two others attacked while the overseers were distracted by Ruth’s assault and within seconds all three plantation authority figures were on the ground disarmed and injured seriously enough that they wouldn’t be pursuing anyone immediately.

Run! Ruth shouted to her group toward the coast. Stay together. They ran through storm and darkness, leaving Ravenswood’s main complex behind. behind them. Alarms were being raised as the injured overseers managed to alert others. But Ruth’s group had perhaps a 15-minute head start before organized pursuit could begin.

Ruth’s plan had been to reach Charleston’s waterfront, approximately 8 mi distant, where Gabriel had contacts among the free black community, who might provide temporary shelter and information about ships departing for northern ports. But reaching Charleston required covering significant distance across open country where they’d be visible once daylight came.

And they had to do it while slave catchers organized pursuit with dogs and weapons. They ran through fields and woods stumbling in darkness over ground made treacherous by rain and mud. Driven by fear and hope and Ruth’s unshakable will to avoid capture. Some struggled to keep pace with Ruth’s longer stride and superior conditioning.

and Ruth would fall back to help them, using her strength to literally carry people when necessary, refusing to leave anyone behind, despite knowing that slowing down increased capture risks for everyone. By dawn, they’d reached the marshy wetlands that bordered Charleston’s northern approach. They could see the city in the distance.

Church steeples and warehouse roofs visible through morning haze. So close but separated by tidal creeks and mudflats that would be difficult to cross quickly. Behind them they could hear sounds of pursuit, dogs barking, men shouting. The organized chaos of slave catchers beginning their hunt with the methodical efficiency that came from years of experience tracking fugitives through the low country’s difficult terrain.

Ruth understood that their brief window was closing rapidly. That within hours professional trackers would be following their trail with dogs trained specifically for this purpose and armed men who wouldn’t hesitate to use violence. into the marsh, Ruth commanded. The water will hide our scent from the dogs, at least temporarily. Stay close to me, and watch for deep channels.

They entered the wetland, cold water rising to their waists, mud sucking at their feet with each step, marsh grass cutting their hands as they pushed through dense vegetation. The crossing took more than 2 hours, during which time two people nearly drowned in deep channels and had to be rescued by Ruth, whose height and strength allowed her to maintain footing where others couldn’t.

They eventually reached firmer ground on Charleston’s outskirts, exhausted and terrified, but still free. Ruth led them into the maze of alleys and back streets that characterize Charleston’s working districts. Areas where free black laborers, enslaved people on errands for their owners, and suspicious white observers all mixed in complicated patterns.

Gabriel had told Ruth to look for a boarding house on Street, run by a free black woman named Sarah Grimble, who sometimes provided shelter to fugitives. Finding the location in daylight, while avoiding slave catchers and suspicious white citizens who might report them, required moving carefully through streets where their wet, muddy appearance and obvious exhaustion made them stand out dangerously.

They eventually located the boarding house. A modest two-story wooden structure that looked unremarkable from outside. Ruth approached the door and knocked, hoping desperately that Gabriel’s information was accurate and that Sarah Grimble would be willing to risk everything to help strangers. The door opened to reveal a woman in her 50s, her expression weary but not hostile.

Ruth spoke quickly, identifying herself as coming from Ravenswood and saying that Gabriel had sent them. Sarah Grimble’s expression shifted immediately to something between concern and resignation. the look of someone who’d known this moment might come and had been dreading it. She pulled them inside quickly, closing the door and checking the street to ensure no one had observed their arrival.

The boarding house’s interior was cramped and dark, but it was dry and warm and represented the first moment of relative safety Ruth’s group had experienced since fleeing Ravenswood 12 hours earlier. Sarah provided them with dry clothing, food, and information about their situation that was grimly realistic. Slave catchers were already in Charleston searching for fugitives from Ravenswood.

Cornelius Ashford had offered a substantial reward for Ruth’s capture, $300, an enormous sum that would motivate every slave catcher and bounty hunter in the region. Charleston’s white population was on alert for suspicious groups of black people, and the city guard had been notified to watch for fugitives.

Sarah could provide shelter for perhaps 2 days at most before the risk of discovery became too great, and she had limited resources for helping them move beyond Charleston. The situation was desperate, but not completely hopeless. Sarah explained that a ship named the Providence was scheduled to depart Charleston on December 16th, 3 days away, bound for Philadelphia with a captain known to be sympathetic to fugitives.

If Ruth’s group could remain hidden until then, and get to the docks without being captured, they might be able to secure passage north. But the weight would be extraordinarily dangerous, and moving 13 people through Charleston to the waterfront without being discovered would require careful planning and significant luck.

Ruth listened to all of this while trying to manage her own exhaustion and the psychological whiplash of being closer to freedom than she’d ever been, while simultaneously being more vulnerable than at any point during her 15 years of enslavement. She thanked Sarah for her willingness to help and asked what they could do to minimize the risk to her.

Sarah’s response was pragmatic and sobering. The best thing they could do was remain absolutely quiet and hidden, avoid any contact with the outside, and be prepared to flee immediately if slave catchers came to the boarding house. Sarah would try to gather information about the Providence’s exact departure time and arrange for someone to guide them to the docks when the moment came, but she couldn’t guarantee anything beyond temporary shelter.

Over the next two days, Ruth’s group remained in Sarah Grimald’s boarding house, 13 people crowded into two small attic rooms, barely moving during daylight hours when noise might draw attention. They could hear the city beyond the walls. street vendors calling their wares, carriages passing, occasionally slave catchers making inquiries at nearby buildings.

Each sound created tension that made breathing difficult, and everyone remained in a state of constant alert that was mentally exhausting, even while their bodies rested from the flight. Sarah brought them food and information periodically, and the news was increasingly concerning. Cornelius had increased the reward for Ruth’s capture to $500, and Thomas Hrix had arrived in Charleston personally to coordinate with slave catchers, furious about losing his investment and determined to see Ruth captured. Professional slave catchers