The air in Natchez, Mississippi hung thick and wet in the summer of 1844. The kind of heat that made every breath feel like drowning. The Asheford plantation stretched across 1500 acres of cotton fields, where rows of white bowls swayed under a merciless sun. 200 souls labored there, their backs bent, their hands bleeding, their songs rising and falling like prayers that would never be answered.

Among them was a man named Isaiah. He was 32 years old, tall and lean, with hands scarred from years of picking cotton and cutting cane. His eyes held something the overseers didn’t like, a sharpness, a refusal to look away when spoken to. Isaiah had been born on the Asheford plantation, as had his father before him. He knew every inch of that cursed land, every hiding place in the woods, every loose board in the barn. He also knew how to read.

His mother had taught him in secret, scratching letters in the dirt behind the quarters after dark, whispering the sounds until they became words. Words until they became sentences. It was the most dangerous gift she could have given him. And she died knowing it might get him killed. But she’d also died believing that a man who could read could never be completely enslaved.

Isaiah kept his literacy hidden like a blade. On a Thursday morning in late July, everything changed. The overseer, a red-faced man named Cyrus Hewitt, rode into the slave quarters before dawn, his horse kicking up dust. Behind him came two patrollers and Master Ashford himself, a rare and terrible sight. Thomas Ashford was a thin man with gray hair and cold blue eyes, the kind of man who smiled when he ordered a whipping.

Bring out Isaiah,” Huitt shouted. Isaiah emerged from his cabin, his wife Rebecca clutching his arm, their six-year-old daughter Sarah, hiding behind her mother’s skirts. His heart hammered in his chest, but he kept his face calm. “You’ve been teaching slaves to read,” Ashford said. It wasn’t a question. Isaiah’s blood turned to ice. “No, sir.

Don’t lie to me, boy.” Ashford held up a piece of paper, a crude drawing with letters scratched beneath it. Found this in the children’s quarter. You think I’m stupid? The drawing was of a bird. Beneath it in careful letters f e d o m. Isaiah had never seen it before. But he knew it didn’t matter.

Someone had learned something somehow. And now they needed someone to blame. I didn’t write that, sir. Then who did? I don’t know, sir. Ashford’s smile was terrible. We’ll see about that. Before we continue this journey into one of Mississippi’s darkest and most unspeakable stories, I need to ask you something.

Where are you watching from? Drop your location in the comments. And if this is your first time on our channel, subscribe now because what you’re about to hear is a story that official history tried to bury but memory refused to forget. They dragged Isaiah to the barn while his wife screamed and his daughter wept. The other slaves watched from their cabins, silent, their faces carved from stone.

Everyone [clears throat] knew what happened to those accused of teaching. Everyone knew the punishments that awaited. But what they didn’t know, what no one could have known, was that Thomas Ashford had recently returned from New Orleans with a new method of correction, one he’d heard about from other plantation owners over whiskey and cigars.

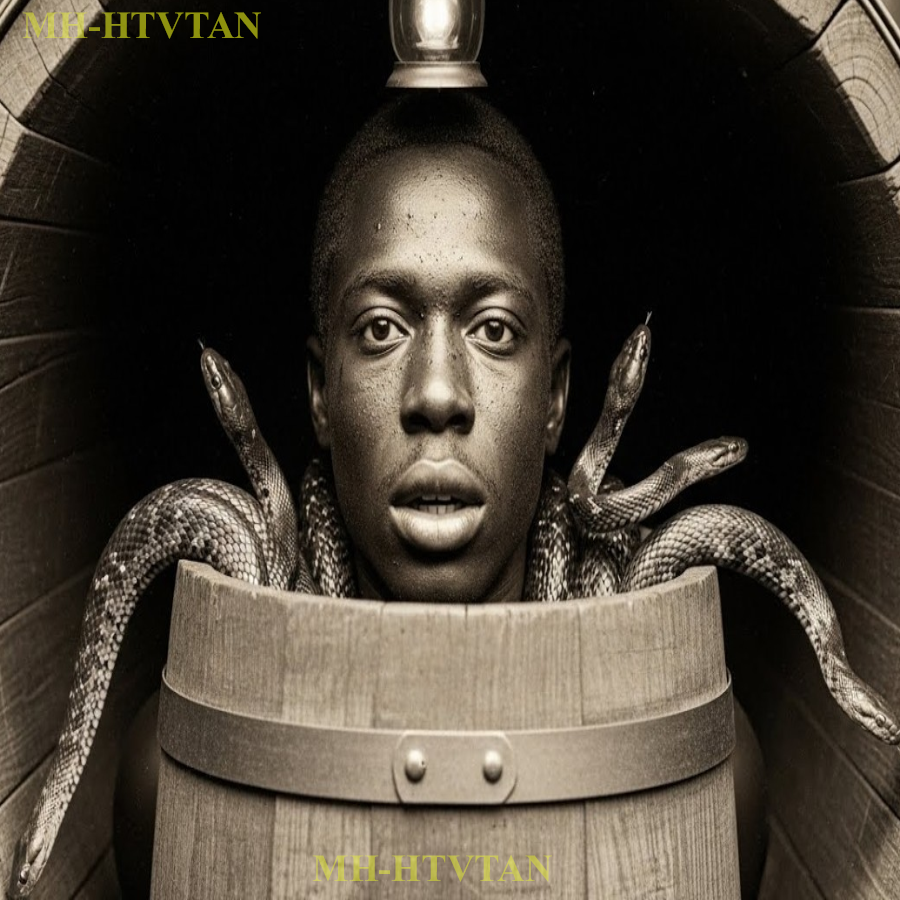

In the barn stood a large oak barrel reinforced with iron bands. And inside that barrel, coiled in the darkness, were three water moccasins, thick-bodied snakes with venom that could kill a man in hours, brought up from the swamp specifically for this purpose. Isaiah saw the barrel and understood immediately. This wasn’t about confession.

This wasn’t about justice. This was about terror, about making an example so horrifying that no slave would ever dare touch a book again. Huitt grabbed Isaiah by the collar. You got one chance to confess, boy. Tell us who else you taught, and maybe the master shows mercy. Isaiah looked at his wife, at his daughter, at the faces of everyone he’d ever known.

Then he looked at Ashford and said, “I got nothing to confess.” The master’s smile widened. put him in. They stripped Isaiah to his waist and bound his hands behind his back with rough hemp rope that cut into his wrists. Four men, Huitt and three patrollers, grabbed him by the arms and legs. He didn’t struggle. There was no point.

Struggling would only give them more reason to hurt Rebecca and Sarah. The barrel stood 7 ft tall and 4t wide, its wood stained dark from years of holding salted pork. Now it held something else entirely. Through the gaps in the planks, Isaiah could hear movement. The dry whisper of scales against wood, the slow, patient breathing of predators.

“Last chance,” Ashford said, standing with his arms crossed. “Who else can read?” Isaiah said nothing. “Your choice.” They lifted him up and over the rim. For a moment, Isaiah hung suspended above the darkness, and he could smell it. The reptilian musk, the damp earth smell of the swamp. Then they dropped him. He fell six feet and landed hard on the barrel’s bottom.

The impact driving the air from his lungs. Immediately he felt them. Cold, muscular bodies sliding away from where he’d landed, repositioning themselves in the cramped space. His eyes hadn’t adjusted to the darkness yet, but he could hear the warning hisses. Could feel the vibrations through the wood as the snakes moved. Above him, a heavy wooden lid slammed down, plunging him into complete blackness.

He heard the sound of a bolt being driven home, locking him in. “We’ll see what comes out in the morning.” Ashford’s voice came through the wood. If you’re alive and ready to talk, maybe we’ll let you out. If not, the master’s laugh was cold. Well, at least the other [ __ ] will learn something. Footsteps retreated. A door slammed, then silence.

Isaiah sat perfectly still in the darkness, his back against the curved wall of the barrel, his bound hands useless behind him. He could feel his heart hammering so hard he thought it might burst through his ribs. The air was already getting close, thick with the smell of snake and his own fear sweat. One of the moccasins hissed, close, maybe 2 ft from his left leg.

Water moccasins were ambush predators. His father had taught him years ago. They didn’t chase you down. They waited, struck when threatened, and their bite was like liquid fire spreading through your veins. In this confined space, even a defensive strike could be fatal. Isaiah forced himself to breathe slowly, shallowly. He needed to think.

He needed to survive until dawn. Rebecca would be praying. Sarah would be crying herself to sleep. They needed him to come out of this barrel alive. But how? His hands were bound. He couldn’t see. And sharing this wooden prison with him were three of the deadliest snakes in Mississippi. He felt movement near his right foot.

A heavy body sliding past. Exploring the snake scales made a sound like sand pouring through an hourglass. Isaiah pressed himself harder against the wall, making himself as small as possible, barely breathing. Hours passed. The darkness was absolute. He lost track of time. lost track of everything except the constant awareness of the snakes moving around him, over him, sometimes across his legs or feet.

Each time one touched him, his muscles locked with terror, but he didn’t move. Couldn’t move. The snakes, he realized, were as trapped as he was. They hadn’t eaten in however long Ashford had kept them in here. They were angry, stressed, dangerous, but they were also conserving energy, waiting for opportunity. Isaiah’s mind began to wander.

He thought about his mother, about the risk she’d taken teaching him to read. He thought about the Bible passages she’d whispered to him, and the truth shall set you free. But there was no truth here that would save him. There was only darkness and scales, and the slow passage of time toward a dawn he might not see.

Somewhere in the deepest part of the night, exhaustion overtook him. His head nodded forward. And despite everything, despite the snakes, despite the terror, Isaiah slept. Isaiah woke to pain shooting through his left arm. For a moment he didn’t remember where he was. Then the smell hit him. Reptile musk and his own sweat, and memory crashed back like a fist.

He’d shifted in his sleep, and his bound arm had pressed against something cold and scaled. The snake had struck reflexively, its fang sinking deep into the muscle of his forearm. The pain was immediate and intense, like someone had driven hot nails through his flesh. Isaiah bit down on his lip to keep from screaming.

Sound might trigger another strike. Movement might trigger another strike. Even breathing felt dangerous now. He could feel the venom already spreading, a burning sensation radiating up from the bite. In the absolute darkness, he couldn’t see the wound. Couldn’t see how bad it was. He could only feel the hot pulse of his blood, the swelling already beginning.

The way his arm was going numb and on fire at the same time. “I’m going to die in here,” he thought. Rebecca will be a widow. Sarah will grow up without a father. But then another thought came, sharp and clear as his mother’s voice. Not yet. You don’t die yet. Isaiah forced himself to breathe through the pain to think.

Water Marcus and venom was hemattoxic. It destroyed blood cells and tissue. A full invenimation could kill a man. But not all bites were full invenimations. Sometimes snakes dry bit, delivering a warning without venom. Sometimes they only injected a small amount. He had no way of knowing which he’d received.

What he did know was that panic would speed his heartbeat, would pump the venom through his system faster, so he couldn’t panic. He had to stay calm. Had to keep his heart rate slow. Had to survive until dawn. The hours crawled by like years. The pain in his arm grew worse, spreading past his elbow now, making his shoulder throbb. Sweat poured down his face.

His mouth was dry as cotton, and thirst began to gnaw at him. The barrel was like an oven, trapping the heat of his body, the breath of the snakes turning the air thick and foul. He drifted in and out of consciousness, fever dreams mixing with waking nightmares. He saw his mother’s face, young and beautiful as she’d been before the plantation broke her.

He saw his wife on their wedding day. Not a real wedding, just a jumping of the broom behind the quarters. But Rebecca had worn a flower in her hair, and her smile had been like sunrise. He saw Sarah learning to write her name in the dirt, the same way he’d learned, the same dangerous gift passing from generation to generation.

“They can’t kill what we know,” his mother whispered in his delirium. “They can lock up our bodies, but our minds stay free. Somewhere in the darkness, one of the snakes hissed. Isaiah’s eyes snapped open. Not that it mattered in the pitch black, but he was suddenly completely alert. The quality of the darkness had changed.

There was the faintest, almost imperceptible lightning at the gaps between the barrels planks. Dawn was coming. He’d survived the night. But the real question remained. What would come out of this barrel when Ashford opened it? a broken man ready to confess to anything, a corpse to be dumped in an unmarked grave or something else entirely.

As the first gray light of dawn seeped through the cracks in the barrel, Isaiah took stock of his situation with a clarity born of pain and rage. His left arm was swollen to nearly twice its normal size, the skin tight and discolored. He could feel that even without seeing it. The venom had spread through his system, making him feverish and weak.

His wrists were raw and bleeding from the rope which had tightened as his hands swelled. His throat was parched, his lips cracked. By any reasonable measure, he should have been defeated. But somewhere during that endless night, locked in darkness with death coiled around him, Isaiah had stopped being afraid. He’d realized something fundamental.

Thomas Ashford had already decided to kill him. Whether it happened in this barrel or on a whipping post or sold down to the sugar plantations of Louisiana where slaves died within 5 years, it didn’t matter. Ashford couldn’t allow a slave who could read to live couldn’t allow the dangerous idea of literacy to spread. So Isaiah had nothing left to lose.

And a man with nothing to lose is the most dangerous creature on earth. He’d spent the night listening to the snakes, learning their patterns. Water moccasins were territorial and aggressive, but they were also predictable. They had favorite corners of the barrel, favorite positions. They moved less as the night cooled, conserving energy.

And Isaiah had spent years working with animals, mules, horses, even the plantation’s hunting dogs. He understood something that Ashford, in his cruelty, had overlooked. Animals respond to confidence. As dawn light grew stronger, Isaiah began to move. Slowly, carefully, he shifted his position in the barrel. His bound hands behind him found the rough wood of the wall, found purchase.

Using his legs and his back, he began to stand inch by painful inch. The snakes stirred, hissing warnings. Isaiah ignored them. He continued rising, his movements deliberate and steady until he was standing upright in the barrel, his head nearly touching the locked lid. One of the moccasins, disturbed by his movement, slithered up his leg.

Isaiah didn’t flinch. He’d learned during the night that sudden movement triggered strikes, but slow, steady movement confused them. The snake explored his calf, its tongue flicking against his skin, tasting his sweat. Then it slid back down and away, finding a more comfortable position. Isaiah’s hands, still bound behind his back, worked at the rope.

The blood and sweat had made it slippery. His fingers were swollen and clumsy from the venom, but he kept working, kept pulling, kept twisting. Outside the barrel, he heard voices. Think he’s still alive? That was one of the patrollers. Don’t matter either way, Huitt’s voice. Master wants him brought to the whipping post after.

Dead or alive, the other [ __ ] need to see what happens. You ever seen a man bit by three moccasins? Saw one bit by one down in the swamp. Died screaming. Took two days. Three? Huitt laughed. He’s probably gone already. The rope around Isaiah’s wrists finally loosened. He pulled his hands free, biting back a cry of pain as blood rushed back into his fingers.

His left arm was almost useless, but his right still worked. He flexed his fingers, feeling returning to them. “Should we open it?” the patroller asked. “Wait for the master. He’ll want to see more footsteps.” Then Thomas Ashford’s voice. “Well, gentlemen, let’s see what hell is made of our teacher.” Isaiah heard the bolt being drawn back.

Sunlight suddenly flooded the barrel as the lid was lifted, blinding him after the long darkness. He squinted against it, raising his good arm to shield his eyes. “Sweet Jesus,” someone breathed. As Isaiah’s eyes adjusted, he looked down at himself and understood their shock. The sight that greeted Thomas Ashford and his men should have been impossible.

Isaiah stood upright in the barrel, his back straight, his eyes blazing with fever and something that looked like madness. His left arm was grotesqually swollen, the skin mottled purple and black from the venom. Blood streaked his wrists where the rope had cut him. Sweat poured down his face and chest. But he was alive, standing, unbroken, and coiled around his right arm like some terrible ornament was one of the water moccasins.

The snake’s head rested on Isaiah’s shoulder, its tongue flicking out, tasting the air. its thick body wrapped three times around his forearm, the muscles rippling beneath the scales. “It should have been striking, should have been pumping more venom into him. Instead, it seemed almost calm. “Get back!” Huitt shouted, stumbling away from the barrel.

“It’s going to strike.” But the snake didn’t strike. It remained where it was, coiled around Isaiah’s arm. As the slave slowly, deliberately climbed out of the barrel. The other two moccasins slithered in the shadows at the bottom, disturbed by the sudden light, but they made no move to follow. Isaiah stood on the barn floor, swaying slightly, and the men backed away from him as if he carried plague.

The snake on his arm shifted, its head rising, and Huitt raised his rifle. “Don’t,” Isaiah said. His voice was rough, cracked from thirst, but it carried an authority that made Huitt freeze. You shoot it strikes. Venom moves fast. It was a bluff. The snake had already bitten him once during the night, and Isaiah suspected it had little venom left.

But the men didn’t know that. They saw what they expected to see, a slave who should have died, but hadn’t, who’d somehow survived a night with deadly serpents who’d emerged with one wrapped around his arm like a familiar. In the superstitious culture of 1844 Mississippi, where slaves whispered about hudoo and root work, where overseers carried rabbit feet and wore mojo bags, this was a sight that bypassed reason and went straight to primal fear.

Thomas Ashford’s face had gone pale. “How you wanted to know who else can read?” Isaiah said, taking a step forward. The circle of men widened. “The answer is nobody. I’m the only one. But you already knew that, didn’t you, Master? Ashford’s hand went to the pistol at his belt. I wouldn’t, Isaiah said softly. The snake’s head rose higher, mouth opening slightly to show the white interior that gave water moccasins their name.

Like I said, venom moves fast, and I got nothing left to lose. The truth was, Isaiah was dying. He could feel it. The venom had spread too far. The fever was too high. His legs were shaking. and it was taking every ounce of strength he had left just to stay standing. But he’d be damned if he died on his knees. “What do you want?” Ashford demanded, trying to regain control.

“You think you can bargain? You’re still a slave, boy. Still my property.” “Property?” Isaiah repeated. The word tasted like poison. More poison than what was already coursing through his veins. “Is that what I am?” He took another step forward, and this time even Ashford backed up. “Then do with your property as you will, master, but first answer me one question.

” Isaiah’s eyes locked on Ashford’s. “What kind of property survives a knight with three moccasins? What kind of property comes out standing with the snake wrapped around his arm like Moses and the serpent?” The biblical reference was deliberate. These men knew their scripture, knew the story of Moses’s staff turning into a snake, knew the power that serpents held in holy rit.

Isaiah was speaking their language now, using their beliefs against them. “You put me in that barrel to break me,” Isaiah continued, “to make an example. But all you did was show every slave on this plantation that you’re afraid. Afraid of words, afraid of knowledge, afraid of what happens when a man knows he’s more than what you call him.

Shoot him, Ashford said to Huitt, but his voice wavered. Huitt raised the rifle, hands shaking. The snake on Isaiah’s arm tensed, sensing the fear in the room, feeding on it. “Wait!” The voice came from the barn door. Everyone turned to see Rebecca standing there, Sarah clutching her hand. Behind them, a crowd of slaves had gathered, drawn by the commotion, by the rumors already spreading through the quarters that something impossible was happening.

Please,” Rebecca said, her voice breaking. “Don’t shoot him. Please,” Ashford’s jaw tightened. The last thing he needed was witnesses, especially not dozens of slaves watching him negotiate with a man who should have been dead. But they were here now, and shooting Isaiah in front of them might spark something worse than literacy, might spark rebellion.

“Get back to the fields,” Ashford ordered. “All of you.” No one moved. Isaiah saw his moment. With the last of his strength, he walked toward his wife and daughter, each step in agony, the world tilting and spinning around him. The snake remained coiled on his arm, its weight both burden and shield.

“Rebecca,” he said softly, “take Sarah. Take her north.” “I’m not leaving you,” Rebecca whispered, tears streaming down her face. “You have to.” Isaiah’s knees began to buckle. He could feel the venom winning. Could feel his heart struggling to pump blood through his damaged veins. The master can’t let me live. We both know it.

But he can’t kill me in front of everyone without looking weak. So he’ll wait. And when he does, Isaiah looked at his daughter at her wide, terrified eyes. Promise me she learns. Promise me she reads. Daddy, Sarah reached for him, but Rebecca held her back. I promise,” Rebecca said, her voice still beneath the tears. Isaiah nodded.

Then his legs gave out completely and he fell to his knees. The snake, sensing the change, unwound itself from his arm and slithered away, disappearing into the shadows of the barn. The crowd of slaves surged forward, but Huitt fired his rifle into the air, stopping them. “That’s enough,” Ashford shouted. Somebody get the doctor.

The rest of you back to work or you’ll join him in the barrel. The threat was hollow, and everyone knew it. You couldn’t put 200 people in barrels with snakes. But the crowd slowly dispersed, whispering, their eyes on Isaiah with something that looked like reverence. Dr. Marcus Webb arrived an hour later, a thin man with spectacles who served as the plantation’s physician.

He examined Isaiah in the barn away from prying eyes with Ashford watching. The bite is bad, Webb said, proddding the swollen arm. Isaiah bit back a scream. Severe invenomation. He should have died hours ago. But he didn’t, Ashford said coldly. No. Webb looked at Isaiah with something approaching respect. He didn’t. I’ve never seen anyone survive a night like that.

His constitution must be extraordinary. Can you save him? Webb hesitated. Possibly with rest, fluids, and constant care. The venom has damaged tissue extensively. But if we can prevent secondary infection, then do it, Ashford said. Webb blinked in surprise. Sir, save him. Ashford’s voice was tight. I won’t have it said that Thomas Ashford’s punishments kill his property.

Bad for business. But his eyes, when they met Isaiah’s, held a different message. You won this round, but I own you. I’ll always own you. Isaiah, drifting in and out of consciousness, managed a smile because he knew something Ashford didn’t. You couldn’t own a man who’d looked death in the eye and refused to blink.

For 3 weeks, Isaiah hovered between life and death. Doctor Webb visited daily, changing the bandages on his arm, administering tinctures and picuses. The venom had destroyed significant muscle tissue, leaving his left arm weak and scarred. Infections set in twice, bringing fevers that made him delirious. But each time, Rebecca’s constant care pulled him back from the edge.

She stayed by his side in their cabin, feeding him broth when he could swallow, bathing his forehead when fever raged, praying when medicine failed. Sarah sat in the corner drawing pictures in the dirt with a stick. Pictures of her father standing tall. Pictures of snakes coiling harmlessly away. Pictures of freedom. The other slaves brought what they could spare.

Extra rations, clean water, herbs from the root woman who lived in the swamp. They came quietly after dark, touching Isaiah’s hand or whispering blessings before slipping back into the night. The story of what had happened in the barn spread like wildfire. Not just through the Asheford plantation, but to neighboring farms, to the slave markets in Nachez, even to the free black communities that existed in hidden pockets throughout Mississippi.

The details changed with each telling. Some said Isaiah had charmed the snakes with ancient African magic. Others claimed he’d spoken the word of God and the serpents had recognized his righteousness. A view said the snakes had been sent by his ancestors to protect him, that his mother’s spirit had watched over him in that barrel.

Isaiah, when he was conscious enough to hear these stories, said nothing to confirm or deny them. He understood the power of myth. Understood that sometimes what people believed was more important than what had actually happened. If the slaves needed to believe he had some special power, some divine protection, then let them believe it.

It gave them hope, and hope was the most dangerous contraband of all. Thomas Ashford understood this, too. He watched the whispers, watched the way other slaves looked at Isaiah when they thought the overseer wasn’t watching. He saw the subtle shift in the plantation’s atmosphere, the way back straightened a little more, the way songs took on a different tone, the way eyes no longer always dropped when white men approached. It infuriated him.

The [ __ ] are getting ideas, Huitt reported one evening, standing in Asheford’s study. They’re not as obedient as they were. Have there been any incidents? Ashford asked. No, sir, but it’s in the air. Like a storm coming. Ashford drummed his fingers on his desk. He’d made a mistake with the barrel.

He realized he’d meant to break Isaiah to terrify the others into submission. Instead, he’d created a symbol, a man who’d survived the unservivable. “Killing Isaiah now would only make things worse. Would turn him into a martr. We’ll sell him,” Ashford decided. As soon as he’s recovered enough to travel, sell him to one of the Louisiana plantations somewhere far away. Out of sight, out of mind.

What about the wife and child? Separate sail, different directions. Ashford’s smile was cruel. Let’s see his god protect him from that. But news of the planned sale reached the slave quarters before the ink dried on the papers. It always did. There were no secrets on a plantation. Slaves who worked in the big house heard everything.

And what they heard they shared. Rebecca came to Isaiah the night she learned. Her face stre with tears. They’re going to sell you, she whispered. Next week, a trader from New Orleans is coming. Isaiah, still weak but stronger than he’d been, took her hand. His left arm was in a sling, the muscles permanently damaged, but his right hand was steady. I know, he said.

You know, how can you? She stopped. You’ve been planning something. It wasn’t a question. Isaiah looked at his daughter, asleep in the corner, then back at his wife. You remember what I told you in the barn? Take Sarah north. Make sure she learns to read. It’s time. Rebecca’s eyes widened. You mean tonight before the trader comes, before they separate us? Isaiah’s voice was low, urgent.

I’ve been talking to Jacob from the Davis plantation. He knows the roots, knows where the safe houses are. The Underground Railroad, Rebecca breathed. Isaiah nodded. The network of abolitionists and free blacks who helped escaped slaves reach the north was more legend than reality in Mississippi. Too far south, too dangerous, too well patrolled. But it existed.

And Isaiah had spent his recovery making connections, passing messages through the invisible network of communication that connected every slave community. “It’s a thousand miles to freedom,” Rebecca said. through swamps and forests with patrollers and dogs hunting us with a child with you barely able to use your arm. I know we could die.

We’re already dying, Isaiah said quietly. Just slowly, at least this way, we die trying to live. They left at midnight when the moon was dark and the patrollers were least vigilant. Isaiah carried Sarah on his good shoulder wrapped in a blanket to keep her quiet. Rebecca carried a bundle with what little they owned, a knife, a tin cup, a piece of cornbread, and the one thing Isaiah treasured most.

A small Bible his mother had stolen from the big house years ago, its pages worn from secret reading. They moved through the cotton fields like shadows. Isaiah’s knowledge of the plantation serving them well. He knew where the overseer slept, knew which dogs were chained and which ran loose, knew the schedule of the night patrol.

They’ timed their escape for the hour between rounds when men grew lazy and complacent. The forest beyond the plantation was dense and dark, full of sounds that made Sarah whimper against her father’s chest. Owls hooted. Things rustled in the undergrowth. The humid air clung to them like wet cloth. “How far to the first stop?” Rebecca whispered. 10 mi.

A farm owned by a Quaker named Thomas. Jacob said to look for a lantern in the barn window. 10 miles. It seemed impossible with a child and an injured man. But they had no choice. Behind them lay slavery and separation. Ahead lay possibility. They walked through the night, stopping only when Sarah needed to rest.

Isaiah’s arm throbbed with each step, the damaged muscles protesting, but he pushed through the pain, driven by the same determination that had kept him alive in the barrel. As Dawn approached, they heard it. Dogs baying in the distance. “They found us missing,” Rebecca said, fear sharp in her voice. “The creek,” Isaiah said, remembering his father’s stories of escapes attempted and failed.

“We need to walk in water throws off the scent.” They found a stream and waded into it. The cold water shocking after the warm night air. Sarah cried out at the temperature, but Rebecca hushed her, holding her close. They moved upstream, slipping on mosscovered rocks, fighting the current. The dogs sounded closer. There, Isaiah pointed to a fallen tree bridging the creek.

We climb across, then double back on the other side, make them think we went downstream. It was a desperate gambit, but it worked. The dogs lost the trail at the fallen tree, their handlers cursing and shouting. The pursuit moved south while Isaiah’s family moved north, stealing precious minutes and miles.

By the time the sun was fully up, they’d covered six of the 10 mi. But they couldn’t travel in daylight. Too visible, too dangerous. They found a dense thicket of blackberry bushes and crawled inside, ignoring the thorns that tore at their clothes and skin. There, hidden in the green darkness, they waited. Sarah fell asleep almost immediately, exhausted.

Rebecca held her, humming softly. Isaiah kept watch, his eyes on the dirt road visible through the branches, his ears attuned to every sound. Around midday, they heard horses. Through the leaves, Isaiah saw Hwitt and two patrollers riding past, their faces grim. Huitt was holding one of Isaiah’s old shirts, letting a blood hound sniff it.

“They’re heading north,” one of the patrollers said, probably trying for the Ohio River. “We’ll catch them,” Huitt replied. “Always do a crippled [ __ ] a woman, and a child. They won’t make it a week.” They rode on. Isaiah waited an hour after they’d passed, then another hour to be safe. When the sun began its descent toward evening, he woke Rebecca.

Four more miles. We travel at dusk, when it’s harder to see us, but we can still see the road. They emerged from the thicket, covered in scratches and bug bites, and continued north. They found the Quaker farm just after full dark, guided by a single lantern burning in the barn window. the signal Jacob had described.

Thomas Garrett was a tall, thin man with kind eyes and workworn hands. He opened the barn door at Isaiah’s quiet knock, took one look at the exhausted family, and ushered them inside without a word. The are safe here, he said in the plain speech of his people. “Come,” he led them to a hidden room beneath the barn floor, accessible only through a trap door concealed under hay bales.

Below was a small space with blankets, water, and bread. How long can we stay? Isaiah asked. Two days, no more. The patrollers know I’m an abolitionist. They search my property regularly, but they don’t know about this room. Garrett studied Isaiah’s injured arm. They are hurt. Snake bite. It’s healing. Garrett’s eyebrows rose, but he didn’t ask for details.

I have medicine and news thee should hear. What news? The patrollers are searching every farm within 20 m. They’re offering a reward for thy capture. $200. That’s more than most bounties. Isaiah understood. The reward wasn’t really about recovering escaped property. It was about Ashford’s pride, about erasing the symbol Isaiah had become.

A man who’d survived the barrel couldn’t be allowed to escape, too. It would make Ashford look weak, would give other slaves dangerous ideas. What’s our next move? Rebecca asked. North to the Tennessee border. I have contacts there who can move thee further along the line, but it’s dangerous. The roads are watched, the rivers patrolled.

They will have to travel through the swamps. The swamps? Rebecca’s face pald. Swamps meant snakes, alligators, disease, and men who hunted escaped slaves for sport. “It’s the only way,” Garrett said gently. “The roads are too dangerous now. But I can provide thee with supplies, a map, and the names of those who will help, if they are brave enough.

” Isaiah looked at his wife, at his daughter, sleeping on a blanket. We didn’t come this far to turn back. For two days they rested in the hidden room while Garrett brought them food and supplies. He also brought news. The search was intensifying. Ashford had brought in professional slave catchers, men who tracked runaways for a living. They had dogs bred specifically for the hunt, and they never gave up.

“There’s something else thee should know,” Garrett said on the second night. “Word of thy story has spread. The slaves call thee the snake charmer. Some say thee have special powers.” Isaiah smiled grimly. I just refused to die. Sometimes that’s power enough. Garrett handed him a package wrapped in oil cloth.

Inside a documents, freedom papers for thee and thy family, forged, but good enough to pass inspection if they are careful. Also a letter of introduction to Frederick Douglas in Rochester, New York. If thee can reach him, he’ll help thee find work and housing. Frederick Douglas. Isaiah knew the name. Every literate slave knew it.

A man who’d escaped bondage and become a voice for abolition. Who published a newspaper. Who proved that former slaves could be scholars and leaders. Why are you helping us? Isaiah asked. Because the light of God is in every person, Garrett said simply. And no man should be another man’s property. Now go, travel only at night.

Trust no one except those I’ve named, and may the Lord watch over thee. On that night they left the Garrett farm and entered the great swamp that stretched between Mississippi and Tennessee, a wilderness of cyprress and cottonmouth, of quicksand and confederate sympathizers, of hope and horror intertwined like the roots of ancient trees.

Behind them the dogs were coming. Ahead lay freedom if they could survive long enough to reach it. The swamp nearly killed them a dozen times. On the third night, Isaiah stepped into quicksand and began sinking. Only Rebecca’s quick thinking, using a fallen branch to pull him out, saved him. They lost their shoes to the mud, continued barefoot, their feet cut and bleeding.

On the fifth night, they encountered an alligator on the narrow path they were following. Isaiah stood between it and his family, holding a torch he’d made from pine resin until the creature grew bored and slid back into the dark water. On the seventh night, Sarah developed a fever.

They huddled in a hollow cyprress tree while she shook and burned. Rebecca holding her close, Isaiah wondering if they’d escaped slavery, only to watch their daughter die in a swamp. But the fever broke and they kept moving. The freedom papers Garrett had provided saved them twice. Once when they encountered a group of white travelers on a backcountry road.

Once when they tried to buy food at a small settlement. Each time Isaiah’s hands shook as he presented the documents, certain they’d be exposed as forgeries. Each time the papers passed inspection, they learned to move like ghosts, to read the land, to trust the North Star and the moss on trees.

They learned which plants were safe to eat and which streams safe to drink from. They learned the rhythms of the hunt, when to hide, when to run, when to simply hold still and pray. And slowly, mile by mile, day by day, they moved north. It took them 43 days to reach the Tennessee border. 43 days of walking at night, hiding by day, living on what they could forage or beg.

Isaiah’s arm healed, crooked but functional. Rebecca’s hands developed calluses hard as wood. Sarah learned to walk silent as a deer, to wake without crying, to be brave when everything said to be afraid. They crossed the Tennessee River on a moonless night, clinging to a log, the current pulling at them like hands trying to drag them back.

On the far shore, they collapsed, gasping, hardly believing they’d made it. But Tennessee wasn’t freedom. They still had to reach the Ohio River. Had to cross into Illinois or Indiana. Had to find their way to the true north where fugitive slave laws held less power. They followed the railroad of safe houses.

Moving from Quaker to Methodist to free black communities. Each step a risk, each dawn a miracle. Winter came early that year, and they nearly froze in a barn outside Chattanooga. Spring found them in Kentucky, so close to freedom they could taste it. On a rainy April morning in 1845, nearly 9 months after they’d fled the Asheford plantation, they crossed the Ohio River into Indiana.

Isaiah’s feet touched free soil for the first time in his life. He fell to his knees in the mud, Rebecca beside him, Sarah between them, and they wept. Not from sadness, but from relief so profound it had no other outlet. They’d made it. Against impossible odds, hunted and wounded and afraid, they’d made it.

3 weeks later, they reached Rochester, New York. Frederick Douglas met them in his office. This man who’d walked the same bloody road to freedom. He shook Isaiah’s hand, listened to his story, read the letter from Thomas Garrett. You’re welcome here, Douglas said. We have work for willing hands and minds. Your daughter, she can read.

Not yet, Isaiah said. But she will. Then I know a school. A good school where no one will punish her for learning. Douglas smiled. The masters tried to keep you in darkness, locked you in a barrel with death itself, and you came out standing. That’s not just survival, brother. That’s testimony. Isaiah looked at his wife, at his daughter, at his scarred and crooked arm.

He thought about the long night in the barrel, about the snakes that should have killed him, about every impossible step of their journey. I couldn’t have done it alone, he said. None of us do, Douglas replied. But you did it. And that story, the snake charmer who wouldn’t break, it’s traveling back south, even now, giving people hope, giving them ideas.

And he was right. For years afterward, slaves throughout the South whispered about Isaiah, about the man who’d faced death in a barrel and walked out free. The story grew with each telling, became legend, became the kind of tale that makes the impossible seem possible. Some versions said he’d commanded the snakes through ancient magic.

Others said God had closed the serpent’s mouths like Daniel in the lion’s den. A few said he’d become something other than human in that barrel, a spirit of vengeance, a force of nature. But the truth was simpler and more powerful. Isaiah had simply refused to let them break him. And in that refusal, he’d broken something else.

the illusion that any human being could truly own another. Isaiah lived to see the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. He died in 1889. A free man in a free land, surrounded by grandchildren who’d never known chains. His daughter Sarah became a teacher. His story became a legend. And somewhere in Mississippi, on a plantation that would soon crumble into dust, a barrel full of snakes rotted in an abandoned barn, a monument to cruelty that had failed, to darkness that had met its match in one man’s unbreakable light. The masters had

tried to teach the slaves a lesson about power. Instead, they taught them about resistance.