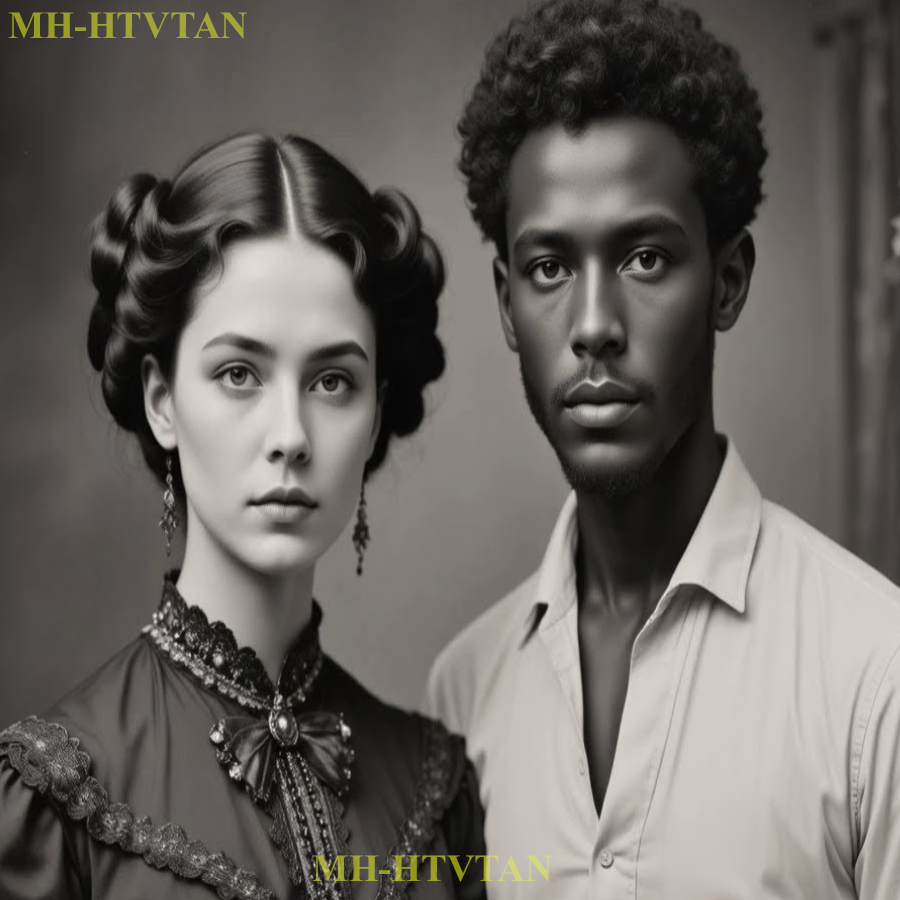

The road to Savannah from Charleston had never seemed so long. The year was 1844 and Genevie Duffrain, newly wed to plantation owner Edward Duffrain, watched as the Spanish moss swayed in the humid Georgia breeze. According to parish records from St. John’s Episcopal Church, the marriage had been arranged between the Duffrain and Bellamy families, uniting two of the wealthiest cotton dynasties in the south.

What those records failed to mention was the hollow look in Genevieve’s eyes as she took her vows, a detail noted only in the private journal of her lady’s maid, Sarah Thompson. Whitfield Plantation sprawled across 800 acres just outside Savannah’s city limits, its white columns rising like sentinels against the darkening sky.

The main house stood three stories tall with 22 rooms, each one meticulously documented in an inventory commissioned by Edward’s father before his passing in 1838. The property housed 73 enslaved persons, their names, ages, and assigned duties cataloged in a leatherbound ledger kept locked in Edward’s study drawer. It was said in Savannah that the Duffrain cotton brought the highest prices at auction, though few questioned the methods that produced such quality.

When Genevieve arrived at Witfield in early March, spring was beginning to touch the grounds with color, but the air inside the house remained stale and oppressive. The previous mistress, Edward’s mother, had died 3 years prior, and the house had been maintained only at the most basic level by the house slaves under Edward’s disinterested supervision.

According to correspondence between Edward and his business associate, James Hartwell, dated April 2nd, 1844, Edward expressed that the acquisition of a wife should finally bring proper order to the domestic sphere. allowing me to focus exclusively on business matters. The first weeks at Whitfield passed in silence for Genevieve.

Her husband spent most days in the fields or at his warehouse in Savannah proper, leaving before dawn and returning well after she had retired. The enslaved house staff moved like ghosts, appearing only when needed, then vanishing again into the shadows of the servants’s quarters or the kitchen house behind the main residence.

From Genevieve’s personal correspondence, later discovered during the renovation of 1962, she wrote to her sister in Charleston, “I find myself a stranger in my own home, speaking more to the walls than to any living soul. It was during her third month at Witfield that Genevieve first noticed him.

According to household records, Noah Langston had been purchased in the Savannah slave market in 1842, classified as a prime field hand despite his lighter complexion and unusual level of education. The purchase receipt preserved in the Georgia Historical Society archives listed him as 26 years of age, strong build, no visible scars, reads and rights, price paid, $1,200.

What the receipt did not record was that Noah had been raised in Philadelphia before being kidnapped and sold south, a fact that would only emerge years later through testimonies collected by abolitionists. Noah had been reassigned from fieldwork to the stables after demonstrating exceptional skill with horses.

The stable stood close enough to the house that Genevieve could observe it from her bedroom window on the second floor. According to entries in her personal diary recovered in a hidden compartment of her writing desk in 1954, she began to watch him daily, noting his movements, the way he spoke softly to the animals, how different his bearing seemed from the other enslaved men on the property.

There is something in his eyes, she wrote on June 17th, something that speaks of places beyond these suffocating acres. When he believes himself unobserved, his posture changes as though momentarily freed from an invisible weight. I wonder what thoughts occupy his mind in those unguarded moments. By midsummer, Genevieve had created reasons to visit the stables.

She developed a sudden interest in riding, requesting that Noah personally prepare her horse each morning. These rides provided brief rest bites from the isolation of the main house. Though according to plantation rules, Noah was required to accompany her at a respectful distance to ensure her safety.

The diary entries from this period grew more frequent, more detailed in their observations, though Genevieve was careful to refer to Noah only as the stable hand, or occasionally L. On August 23rd, her diary recorded, “Today he spoke of Philadelphia. The words slipped from him like water through cupped hands, quickly gathered back and hidden away.

But I had heard enough to know he was not born to this place, not raised in chains. When our eyes met, understanding passed between us. He had revealed too much, and I had heard more than was safe for either of us. What began as curiosity evolved into dangerous fascination. According to kitchen house gossip later documented by WPA writers in the 1930s, the mistress began requesting Noah’s assistance with tasks that should have been assigned to house slaves, repairing a loose shutter near her sitting room, moving furniture in the library, carrying books that she

could easily have managed herself. The head house slave, Martha, reportedly warned Noah of the danger, but he seemed unable or unwilling to create distance. Edward Defrain remained oblivious, his attention consumed by declining cotton prices and increasing pressure from creditors. Business correspondence from this period preserved in the Savannah Merchants Association archives revealed mounting financial difficulties that Edward concealed from his young wife.

A letter dated September 10th from his banker advised immediate reduction of household expenses and consideration of selling non-essential property, including excess slaves to maintain solvency. The first leaves had begun to turn when Genevieve made her boldest move. According to Noah’s own account, dictated years later to a northern journalist, and published anonymously in 1861, she approached him in the stables during a heavy rainstorm when the other workers had sought shelter.

She asked about my life before Witfield, the account stated. When I remained silent, she said she already knew I was not born a slave, that she could tell by my speech, my manner. She offered to teach me to read better books than those available to me, claiming it would be our secret. What Noah couldn’t have known, and what would only be revealed through court records unsealed in 1957, was that Genevieve had already discovered partial truths about his past.

Among her husband’s papers, she had found a letter from the slave trader who had sold Noah, mentioning rumors that the man had been improperly taken from the north, and advising discretion in his treatment and use. Through the cooling days of autumn, Genevie and Noah conducted their clandestine meetings in the small library on the first floor of the main house.

Under the pretense of having him move books or repair shelving, she passed him volumes of poetry and philosophy. According to Martha’s later testimony, Noah would sometimes remain in the library for over an hour, emerging with a carefully neutral expression that failed to hide the light in his eyes. On November 12th, Edward returned unexpectedly from a business trip to find Genevieve reading aloud, while Noah stood nearby.

ostensibly dusting shelves but clearly listening intently. The plantation ledger for that day contains a tur entry. Disciplinary action required for slave Noah reassigned to field gang effective immediately. The entry does not record the 20 lashes Noah received witnessed only by the overseer and three other field hands who were forced to watch as a warning.

Genevieve’s diary falls silent for 2 weeks following this incident. When she resumed writing on November 27th, her handwriting had changed, becoming tighter, more controlled. “I have made a grave error in judgment,” she wrote. “My foolish behavior has caused suffering. I must remember my position, my duties, my place in this household.

But the silence between them would not last. According to estate records, in early December, one of the kitchen slaves fell ill, creating a shortage of house staff. Noah was temporarily brought back to the main house to help move Christmas decorations from the attic and assist with preparations for the annual holiday gathering that the Drains hosted for neighboring plantation families.

It was during these preparations that disaster struck. Martha, who maintained her own secret record of household events in a series of carefully hidden notes found decades later beneath a floorboard in the servants’s quarters, wrote that on December 18th, she observed Genevieve slip a folded paper into Noah’s hand as he carried pine boughs into the main hall.

Hours later, Edward discovered this same paper in his wife’s writing desk, a halffinish letter outlining a plan for Noah’s escape north with Genevieve’s assistance. What followed was recorded only partially and through multiple sometimes contradictory sources. The plantation punishment book shows that Noah was locked in the equipment shed that night to be dealt with in the morning.

Genevieve was confined to her bedroom, the door locked from the outside. According to Martha’s account, the house fell into an uneasy silence, broken only by Edward’s heavy footsteps as he paced the library floor below, occasionally stopping to pour another glass of bourbon. Shortly after midnight, Martha reported hearing the master leave the house.

Approximately 20 minutes later, shouting erupted from the direction of the equipment shed, followed by the sound of a single gunshot. By dawn, rumors had spread through the slave quarters that Noah had somehow escaped his confinement and attacked Edward when discovered. The master had defended himself, firing a shot that missed its target.

Noah had fled into the night, his whereabouts unknown. This version of events became the official narrative recorded in the Chattam County Sheriff’s Report dated December 19th, 1844. A reward notice for Noah’s capture appeared in the Savannah Republican newspaper 3 days later, describing him as dangerous and possibly headed north.

No mention was made of Genevieve’s involvement in the escape plan, but Martha’s hidden notes tell a different story. Mistress somehow got out of her room that night. I heard her light steps on the back stairs. When master left, she followed after. What happened at the shed? Only the three of them know.

But I believe it was the mistress who opened that lock, not the boy breaking out, as they claim. For the remainder of December and into the new year, Genevieve remained sequestered in her room, emerging only for Christmas dinner with Edward’s business associates and their wives. According to the account of Elellanena Hartwell, wife of James Hartwell, who was present that evening, Genevieve appeared like a porcelain figure, beautiful but cold, speaking only when directly addressed, her eyes never meeting her husbands across the

table. By February, Edward had hired a new stable master and publicly put the incident behind him. Genevieve gradually resumed her duties as mistress of Witfield, though household staff noted she rarely ventured beyond the formal gardens anymore. Her riding habit hung untouched in her wardrobe. The truth about that December night might have remained buried forever, known only to those directly involved, had it not been for a discovery made in 1868 after the war, when Witfield Plantation had been abandoned and stood in slow decay. A

northern journalist conducting research for a book on wartime experiences in Georgia explored the derelict property. In the collapsed remains of the equipment shed, he discovered a small tin box that had been concealed in a wall cavity. Inside was a journal, its pages water damaged but partially legible.

The journal belonged to Noah Langston. The entries, later published in part by the journalist, revealed an astonishing truth. Noah Langston was not merely an educated man kidnapped from the north, but Edward Dufra’s half-brother. According to Noah’s account, they shared a father, Elijah Duffrain, who had conducted a long-term relationship with an enslaved woman on his Pennsylvania properties before moving south and establishing himself in Georgia society.

Noah had been raised in Philadelphia by his mother after she gained her freedom, receiving an education and living as a free man until age 24 when he was kidnapped during a business trip to Baltimore and sold south. By terrible coincidence, he had ended up on the plantation owned by his half brother, though Edward never knew of their connection.

Noah had recognized the Duffra name immediately, but kept his identity secret, fearing worse treatment if the truth were known. The final pages of the journal, though heavily damaged, suggested that Noah had revealed his true identity to Genevieve during their library meetings. This revelation, rather than romantic interest, had prompted her offer to help him escape.

The plan had apparently involved providing him with money and papers that would help him establish his rightful claim to freedom once safely in the north. What happened on that December night remains unclear. Noah’s journal ends abruptly on December 17th. The final entry reads, “Tomorrow we make our attempt.

G has secured the necessary papers and funds. If all goes as planned, I will at last reclaim my name and my freedom. If we fail, I pray that this record survives to tell my truth. Genevieve and Edward Duffra remained at Whitfield until 1861, when the outbreak of war prompted them to relocate to Edward’s smaller property in Augusta. According to tax records and personal correspondence, their marriage continued in name, though they maintained separate bedrooms and rarely appeared together in society.

Edward died in 1865 shortly after the war’s end, leaving the already declining Whitfield property to distant cousins, as he and Genevieve had no children. Genevieve returned to her family in Charleston, where she lived quietly until her death in 1882. The journalist who discovered Noah’s journal attempted to trace what became of him after that December night.

Abolitionist records from Philadelphia showed a man matching Noah’s description arriving in the city in early 1845, but he apparently did not stay long. A brief newspaper mention in an 1847 Boston paper referenced a lecture by a Mr. NL recently escaped from Georgia bondage, but no further traces could be found.

What truly transpired between Noah, Genevieve, and Edward on December 18th remains one of the many whispered secrets of Witfield Plantation. The property itself was eventually reclaimed by nature, the main house collapsing in the 1920s after years of neglect. In 1968, during excavations for a new housing development on the former plantation lands, workers uncovered human remains near what had been the equipment shed.

Forensic examination determined they belonged to a male in his late 20s or early 30s, deceased for approximately 120 years. The skull showed evidence of a single gunshot wound. No definitive identification was ever made and the remains were reinterred in an unmarked grave in Savannah’s Colonial Park Cemetery.

The housing development was eventually built, though residents have reported that the area near the old shed site feels unnaturally cold, even in the heat of Georgia summers. The leatherbound ledger from Witfield, now preserved in the Georgia Historical Society, contains one final cryptic entry in Edward’s handwriting, dated December 20th, 1844.

Some secrets must remain buried. The integrity of the Draay name demands nothing less. Whether this referred to Noah’s escape, his true identity, or something darker remains unknown. To this day, visitors to the former Whitfield property sometimes report glimpsing a figure on horseback in the early morning mist, riding toward the old road that once led north to freedom.

The figure never reaches the road’s end, fading from sight as the sun rises higher. Local historians dismiss these sightings as mere legend, while others wonder if some journeys remain unfinished, some truths still striving to be heard. Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of this story is not what we know, but what remains hidden.

How many other families carried such secrets, how many identities were erased, connections severed, truths buried. The rotting papers and crumbling structures of our past hold countless untold stories, waiting in silence for someone to finally listen. Genevieve Durrain’s diary, now housed in the University of Georgia’s special collections, ends with an entry dated January 1st, 1845.

The new year brings no renewal for me. I will perform my duties, maintain appearances, speak when spoken to, but part of me fled into the darkness that night, and I do not expect its return. Some escapes are permanent, others merely illusions. I pray he found the former while I remained trapped in the latter.

The shed where Noah was last seen still stood until 1959, outlasting the main house by decades. Those who explored the abandoned structure often reported an overwhelming sense of despair within its walls, as though the very air remained charged with the emotion of that December night. When the shed was finally demolished, workers found strange markings carved into the interior walls, patterns that some claimed were African protection symbols, while others recognized them as navigational guides used by those following the North Star to freedom. In

1965, an elderly woman claiming to be descended from Martha, the head house slave, came forward with a story passed down through generations in her family. According to this account, neither Edward nor Noah died that night at Witfield. The gunshot was fired into the air during a struggle, and both men survived.

What happened after remains speculation, though the woman insisted that Edward had discovered his relationship to Noah during their confrontation, a revelation that changed everything. The woman’s story could not be verified, and historians generally dismiss it as folklore. Yet certain inconsistencies in the official records, Edward’s unexplained 2-week absence in January 1845, unusual withdrawals from his accounts, and letters referring to a family matter requiring discretion, suggest there may be truth hidden within the tale.

Whitfield Plantation has long since vanished, its boundaries blurred by time and development, but the questions it raises remain relevant. What defines family? How do we reconcile with hidden truths? And can we ever fully escape the shadows of the past? Perhaps the only certainty in this story is its uncertainty.

The fragments of lives preserved in ink and memory, pieces of a puzzle that will never be complete. Like so many chapters of our collective history, the true story of Genevieve Duffrain and Noah Langston exists somewhere in the space between documented fact and fading memory, between what was recorded and what was deliberately erased.

The Spanish moss still sways in the Georgia breeze, whispering secrets we may never fully understand. In 1954, during the renovation of an old courthouse in downtown Savannah, workers discovered a sealed compartment behind a bookshelf in what had once been a judge’s private chambers. Inside was a packet of letters tied with faded blue ribbon, addressed to GD, and signed only with the initial N. The letters had never been sent.

County records identified the chamers’s occupant in 1845 through 1848 as Judge William Harrington, who had presided over several notable cases involving disputed property rights after the death of prominent citizens. According to his personal journal kept in the Savannah Historical Society archives, Harrington had a distant family connection to the Duffrains through his wife’s sister’s marriage.

The letters, now preserved in acid-free containers at the Georgia State Archives, contain what appears to be Noah Langston’s account of his life after that December night at Whitfield. The handwriting matches that of the journal found in the equipment shed, though experts note signs of physical strain or injury in the earlier entries. According to these letters, Noah did indeed escape that night, but not alone.

The first letter dated February 3rd, 1845 begins, “My dearest G, I write these words knowing they cannot reach you. Yet I cannot bear the thought of you believing I perish that night. The truth of what happened is far stranger than any fiction we read together in those stolen hours.” The letter goes on to describe how Edward, upon confronting Noah and Genevieve at the shed, had indeed fired a shot, but into the ground, not at Noah.

What followed was a revelation that changed everything. According to Noah’s account, he had been forced to reveal his true identity as Edward’s half-brother to prevent violence. The look on his face, Noah wrote, as understanding dawned, was something I shall never forget. Disbelief gave way to rage, then to a cold calculation I recognized from our father’s expressions.

In that moment, he saw not just the betrayal of his wife and property, but the potential scandal that could destroy the Drain name completely. What happened next contradicts all official accounts. Noah claims that Edward, after an hour of intense conversation, made a proposition Noah would disappear, presumably escaping north.

Edward would report the escape and make a show of trying to recover his property. But in reality, Edward would provide funds for Noah to establish himself far away under a new name, on the condition that the truth of their relationship never be revealed. He feared the scandal more than he desired revenge. Noah wrote, “The great Edward Duffrain, Scion of Georgia society, sharing blood with a man he had unknowingly enslaved.

Such a revelation would destroy not just his standing, but the legitimacy of everything the Drain name represented. The most shocking claim in the letters is that Edward himself helped stage the escape, firing the shot that would be reported and creating evidence of a struggle. According to Noah, Edward’s primary concern was containing the damage to his reputation, not punishing either his wife or his newly discovered half-brother.

The second letter dated April 10th, 1845 finds Noah established in Cincinnati under the name Nathan Lewis. I have secured employment with a printing house, he wrote. The owner asks few questions of his employees concerned only with their ability to operate the machines and meet deadlines. The irony does not escape me.

I now produce the very newspapers that once advertised rewards for my capture. Throughout the six letters spanning 1845 to 1847, Noah expresses concern for Genevieve’s well-being. I fear what life must be for you now, trapped in that house with him, both of you bound by secrets. Has he punished you? Or does the greater punishment come from the silence, the pretense that nothing happened, nothing changed? The final letter dated November 12th, 1847 suggests that Noah had received some news about the Duffrains.

Word has reached me of E’s financial troubles and your removal to Augusta. I wonder if the loss of Witfield brings you pain or relief. That place held nothing but shadows for both of us, though for different reasons. I have heard rumors too of your separate lives within the same household, a prison of propriety that perhaps hurts more than iron chains ever could.

The letter concludes with, “I shall not write again after this.” These words, like those before, will never reach you. But perhaps someday, when all those who might be hurt by these truths have turned to dust, someone will find these pages and know that Noah Langston lived, survived, and carried the memory of those brief moments of honesty in the Witfield Library until his last breath.

How these unscent letters came to be in Judge Harrington’s private chamber remains unknown. One theory proposed by historians suggests that Noah may have sent them to the judge seeking legal counsel about potentially claiming his rightful inheritance as Elijah Durrain’s son only to abandon the effort.

Others speculate that Edward himself might have intercepted the letters and given them to Harrington for safekeeping or legal advice regarding the potential scandal. In 1868, the same year the journalist discovered Noah’s journal in the collapsed shed, a small obituary appeared in a Cincinnati newspaper for Nathan Lewis, printer and respected community member, aged approximately 50 years.

The notice mentioned that Lewis had no known family, but was mourned by colleagues and friends, who described him as a man of quiet dignity, who carried himself as though bearing an invisible burden. Cemetery records show that Lewis was buried in a modest plot purchased years earlier with a simple headstone bearing his adopted name and the dates cine118 to 1868.

Beneath the dates is inscribed a single line, freedom once gained is never forgotten. Whether this referred to his escape from slavery or from something else entirely remains a matter of speculation. The Witfield plantation lands changed hands multiple times in the decades following the Civil War.

By the turn of the century, the once grand estate had been subdivided into smaller farms, the main house abandoned and falling into decay. Local children told stories of seeing lights in the upper windows at night, though the house had no electricity and no official occupants. In 1923, a severe storm brought down the remaining structure, scattering the last physical remnants of the Dufra legacy across the overgrown fields.

According to a newspaper account of the collapse, cleanup crews discovered numerous personal items in the rubble. broken china, tarnished silver, fragments of furniture, and most notably a small portrait miniature of a woman identified by local historians as Genevieve Duffrain in her youth. The portrait, now displayed in the Savannah Historical Museum, shows a young woman with dark hair and serious eyes.