Every spring between 1843 and 1847, at least seven daughters from Mississippi’s wealthiest plantation families vanished without a trace. No bodies were ever found. No investigations were ever completed. The families claimed their daughters had been sent to European finishing schools or married distant cousins in Charleston.

But in the forgotten archives of Adams County, there exists a leatherbound diary that tells a different story. A story of a treatment so brutal, so methodically cruel that three men were willing to risk their lives to stop it. This is the account of what really happened in the barn at Kellerman estate and why Catherine Kellerman’s body was never found.

The truth about Katherine Kellerman’s fate began with her mother’s obsession, but it ended with a revelation that would shake the foundations of Mississippi’s elite society. Nachez, Mississippi, in the spring of 1843 stood as a monument to southern prosperity and carefully maintained appearances.

The city’s plantation families competed not just in cotton yields and land holdings, but in the perfection of their bloodlines, the elegance of their daughters, and the absolute control they wielded over every aspect of their domain. Along the bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River, mansions rose like white temples, each one proclaiming its owner’s superiority through Greek columns and manicured gardens that required dozens of enslaved hands to maintain.

The Kellerman estate occupied nearly 4,000 acres of prime cotton land 15 miles northeast of Nachez proper. Lucinda Kellerman had inherited the property from her father in 1831, a rare occurrence that made her both wealthy and deeply resentful of the scrutiny such independence brought. At 42 years old, she had transformed herself into the arbiter of social acceptability among the plantation elite.

Her dinner parties were legendary for their exactitude. The silver had to gleam at precisely the right angle. The flowers had to be arranged in the French style she had studied during a brief stay in New Orleans. Her own figure remained reed thin through a regimen of vinegar water and tight corseting that left her perpetually breathless but undeniably fashionable.

Catherine Kellerman at 19 years old represented everything her mother despised. where Lucinda was angular and sharp, Catherine had inherited her deceased father’s tendency toward weight. By the standards of 1843, she was considered grotesqually obese, her body refusing to conform to the willowy ideal that Lucinda worshiped. But Catherine’s size was not merely a physical characteristic to her mother.

It was a deliberate rebellion, a public humiliation, a stain on the Kellerman name that grew more pronounced with each passing month. She eats like a field hand, Lucinda would say to her closest confidants, her voice dripping with disgust. I have given her every advantage, every opportunity to become a lady of quality, and she repays me with this grotesque display of indulgence.

What Lucinda never mentioned, what she perhaps could not admit even to herself, was that Catherine’s weight had begun its dramatic increase following the death of her father, Thomas Kellerman, in 1839. The official cause had been heart failure. The whispered truth, known only to a select few, was that Thomas had died in his study with an empty bottle of Lordinham beside him, and a letter to Catherine clutched in his hand, a letter that Lucinda had burned before anyone else could read it.

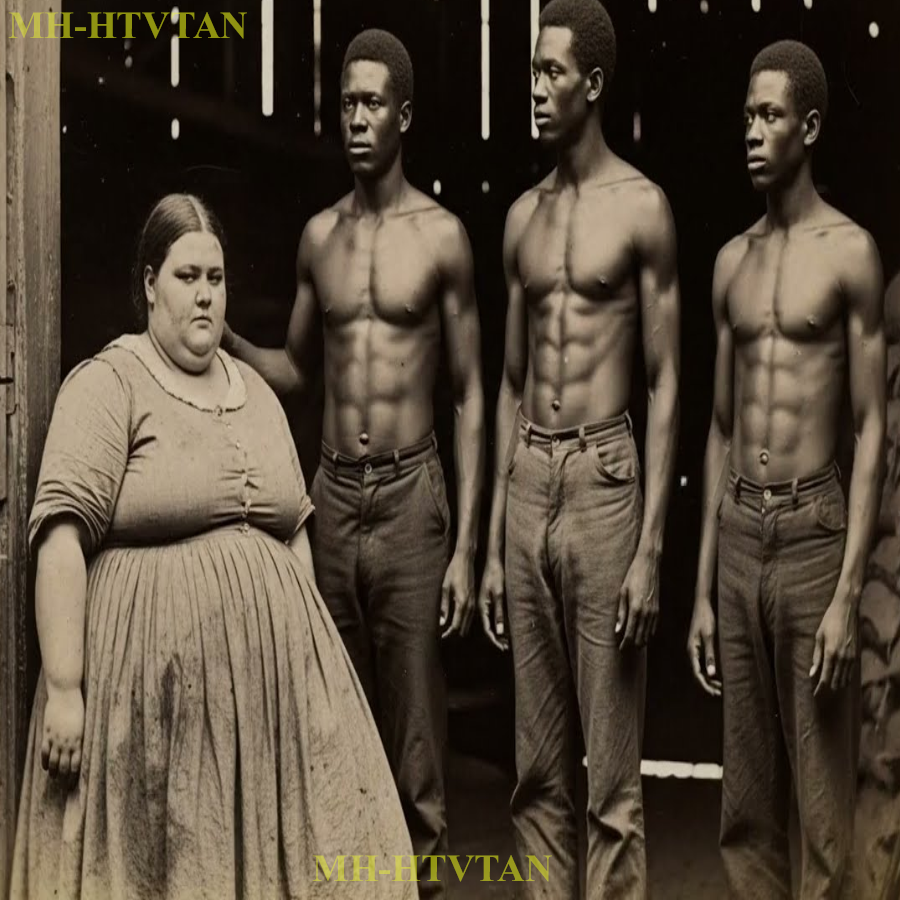

The Kellerman plantation operated with the brutal efficiency that Lucinda demanded in all things. 237 enslaved people worked the cotton fields, the house, the gardens, and the various outbuildings that kept the estate functioning. Among them were three men who would become central to Catherine’s story, though none of them could have anticipated the roles they would be forced to play.

Joshua Fletcher was 34 years old, born on the Kellerman plantation, and trained from childhood as a blacksmith. His hands, scarred from years of hammer work, possessed a strength that made him valuable for any task requiring raw power. He spoke little, observed much, and kept a mental catalog of every cruelty he witnessed, storing them away like coins he might one day spend on justice.

The second man, Samuel Hayes, had been purchased at a Nachez auction in 1841. At 28, he had already survived three different owners, each one worse than the last. What made Samuel valuable to Lucinda was not just his physical strength, but his literacy. His previous owner, a bankrupt merchant, had used Samuel to keep accounts, a skill that was both rare and dangerous for an enslaved person to possess.

Lucinda saw utility in this education, using Samuel to manage the plantation’s grain stores and livestock records, always under her watchful supervision. The third was a 16-year-old boy named Daniel Cooper, purchased specifically for his youth and strength from a failing plantation in Louisiana. Daniel had witnessed horrors in his short life that had left him with a stutter and a tendency to flinch at sudden movements.

But he was also observant in ways that others missed, noticing patterns and details that would later prove crucial. The barn where Catherine’s story would unfold stood at the eastern edge of the main property. A massive structure built in 1820 to store cotton bales before they were transported to the river.

By 1843, a newer warehouse had been constructed closer to the water, and the old barn had been relegated to grain storage and equipment repair. It was isolated from the main house by a grove of live oaks invisible from the mansion’s windows, a perfect place for activities that required discretion. Lucinda’s diary, discovered decades later in a false bottom of a trunk, reveals the exact moment when her plan took shape.

The entry dated March 15, 1843 reads, “Today I observed the Ashworth girl, once a plump and unmarriageable creature, now transformed into a vision of delicate beauty. Mrs. Ashworth confided in me the method of this miraculous change, labor, constant, unrelenting physical labor. The body, when pushed beyond its limits, consumes itself.

It burns away the excess, revealing the form that God intended. Why should this remedy be available only to the Ashworths? Why should my own daughter remain a monument to gluttony when salvation is so simple? I have the means. I have the place. I have the workers who will obey without question. Catherine’s transformation begins tomorrow.

what Lucinda did not write. But what would later become clear was that Margaret Ashworth’s transformation had come at a terrible cost. The girl had developed a persistent cough that no doctor could cure. Her hands shook constantly. Her eyes held a vacant quality that suggested something fundamental had broken inside her.

But she was thin, and in Lucinda Kellerman’s world, that was all that mattered. The social structure of Nachez society in 1843 operated on layers of secrets and silent agreements. Everyone knew things they pretended not to know. Everyone saw things they agreed not to see. This conspiracy of silence was not passive.

It was actively maintained through careful social engineering. To question another family’s private business was to invite questions about one’s own. To express concern for a daughter’s welfare was to suggest that one’s own methods of child rearing might be suspect. The system protected itself through mutual complicity.

Lucinda Kellerman had built her reputation on understanding and exploiting these unspoken rules. She knew exactly how far she could push the boundaries of acceptable behavior before crossing into scandal. She knew which families would ask no questions, which doctors would provide certificates of health without examination, which ministers would preach about the virtue of discipline without specifying its methods.

On March 16th, 1843, Lucinda summoned Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel to the main house. It was unusual for field workers to be brought into the parlor, and the three men stood uncomfortably among the fine furniture and delicate china, acutely aware that their very presence violated the careful boundaries that kept the plantation’s dual realities separate.

“Gentlemen,” Lucinda began, her voice carrying the false warmth she used when giving orders she expected to be obeyed without question. “I have a special task for you. My daughter Catherine requires physical rehabilitation. She has become weak and indolent, unsuited for the duties that will one day befall her as mistress of this estate.

You will oversee her daily labors in the east barn. You will ensure she works from dawn until dusk. You will document her progress in a ledger I will provide, and you will speak of this to no one under penalty of punishment. I trust I do not need to describe. The threat hung in the air, unspoken but understood.

Disobedience meant the whip, the sail to the brutal sugar plantations of Louisiana, or worse. But there was something in Lucinda’s eyes that went beyond the usual cruelty of an owner enforcing her will. There was anticipation, almost excitement, as if she were about to conduct an experiment whose results she eagerly awaited. Catherine herself was not consulted about this arrangement.

On the morning of March 17th, she was led from her bedroom by her mother’s personal maid and taken to the barn, still wearing her night dress under a simple work dress that Lucinda had selected. The girl’s face showed no surprise, only a deep resignation that suggested this was merely the latest in a long series of humiliations her mother had devised.

The first morning in the barn began with mechanical efficiency that felt rehearsed, as if Lucinda had planned every detail of Catherine’s degradation. Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel had been given their instructions with military precision. Catherine was to grind corn using the manual stone mill, carry 50 lb sacks of grain from one end of the barn to the other, and split firewood until her hands blistered.

The work was designed not for productivity, but for exhaustion. Each task calibrated to push her body beyond its limits while producing just enough useful output to justify the labor if anyone asked questions. The barn itself amplified every sound. The grinding of stone against grain echoed off the high ceiling.

Catherine’s labored breathing became a rhythm that the three men found themselves unconsciously matching. The creek of the building’s old timbers seemed to mark time like a clock. Each groan of wood a reminder of hours passing in brutal sameness. What struck Samuel most in those first days was Catherine’s silence. She did not complain. She did not plead.

She did not even speak except to ask for water, which they were instructed to provide sparingly. Her face remained expressionless as she worked as if she had removed herself from her body and was watching from a great distance. Lucinda arrived each afternoon at precisely 3:00, her skirts rustling against the barn floor as she circled her daughter like a buyer inspecting livestock.

She carried a leather journal and in it she recorded measurements, observations, and assessments with clinical detachment. Weight estimated 195 pounds, she wrote on March 20th. Face remains bloated. Arms show slight reduction in circumference. Hands developing calluses, which is unfortunate but necessary. Temperament appropriately subdued.

The treatment progresses as expected. But Lucinda’s journal entries told only part of the story. What she did not record were the private conversations she was having with other plantation ladies who had daughters they considered problematic. Mrs. Helena Cartwright, whose daughter Rebecca had been caught reading abolitionist literature smuggled from the north. Mrs.

Beatatric Singleton, whose daughter Emma had refused three suitable marriage proposals, insisting she wanted to study medicine. Mrs. Constance Whitfield, whose daughter Sarah had been discovered teaching enslaved children to read in secret. These women visited Kellerman estate under various pretenses, afternoon tea, garden consultations, discussions of upcoming social events, but they always asked to see the barn, and Lucinda always obliged, leading them through the grove of oaks to witness Catherine’s transformation. You see,

Lucinda would say, gesturing to her daughter’s exhausted form. The body responds to discipline just as the spirit does. 3 weeks of proper labor, and already the excess begins to melt away. Imagine what 3 months might accomplish, 6 months, a year. The visitors took notes. They asked questions about methods, duration, supervision.

They inquired about dietary restrictions and whether Catherine was permitted any leisure time. Lucinda answered each question with the enthusiasm of a scientist, sharing breakthrough research. No leisure, she confirmed. Leisure is what created this problem. Idleness and indulgence are sisters breeding weakness in our daughters.

Here Catherine learns the value of work. She learns that comfort must be earned. She learns that her body is not her own to ruin with gluttony. By April, the first of the other girls arrived. Rebecca Cartwright was delivered to a barn on her family’s property, overseen by three enslaved men who had been given the same instructions as Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel.

Emma Singleton followed two weeks later, then Sarah Whitfield. Each family modified the approach to suit their particular needs, but the core remained the same. isolation, labor, and the breaking of will disguised as physical improvement. What none of these mothers anticipated was that their daughters might speak to one another.

The plantations were spread across the county, but enslaved workers moved between properties carrying messages and news. Daniel, who was sometimes sent to deliver grain to neighboring estates, began to notice a pattern. Barnes that had been used for storage were suddenly off limits. Young white women who had been fixtures at social gatherings were suddenly absent.

Their mothers explaining they were unwell or visiting relatives. “There are others,” Daniel whispered to Samuel one evening as they secured the barn for the night. “I seen them, girls working like Catherine, looking just as tired, just as scared.” Samuel felt something cold settle in his stomach.

What they were witnessing was not an isolated act of cruelty. It was a system carefully constructed and expanding. Inside the barn, something unexpected was happening to Catherine. The work was brutal, designed to break her, but it was also the first time in years she had been away from her mother’s constant scrutiny and criticism.

In the barn, she was simply a body performing tasks. There were no mirrors to reflect her failure to meet impossible standards. There were no dinner parties where she was displayed as evidence of her mother’s disappointment. And there were Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel who treated her with a careful respect that surprised her. They did not mock her size.

They did not comment on her appearance. When she struggled with a particularly heavy load, Joshua would quietly position himself to take some of the weight without making it obvious. When her hands bled from the rough wood, Samuel brought clean rags and showed her how to wrap them to prevent infection. When she stumbled from exhaustion, Daniel caught her and studied her without judgment.

The first time Catherine spoke beyond requesting water was on April 8th, 6 weeks into her confinement. She was resting during the brief noon break, and Joshua was repairing a piece of equipment nearby. “Do you hate me?” she asked quietly. Joshua’s hands stilled on the tools. He did not look at her directly, knowing such eye contact could be seen as insubordination if anyone observed them.

No, miss,” he replied carefully. “You should,” Catherine continued. “I am everything you should hate. The daughter of your owner, living in comfort while you suffer. I would hate me.” Joshua chose his words with the caution of a man who knew that honesty could cost him his life. “Hate takes energy, miss. Energy better spent on surviving.

” It was a simple statement, but it opened something in Catherine. For the first time, she began to see the three men not as extensions of her mother’s will, but as human beings trapped in the same cruel system, albeit in profoundly different ways. The conversations grew longer, always conducted in careful whispers during breaks or in the early morning before Lucinda’s inspection.

Catherine learned that Joshua had a wife and two children living in the quarters, that Samuel had once lived in a city and could read and write better than most white men. that Daniel dreamed of the freedom he might never experience. In turn, the men learned about Catherine’s life in the mansion, which was its own form of imprisonment, the endless rules about deport and dress, the constant criticism of every bite of food, every word spoken, every breath taken, the isolation from other young people her age because her mother deemed her too

shameful to be seen. She wants me to disappear, Catherine said one morning in May. She wants the daughter she imagined, not the one she has. I think she hoped this work would kill me so she could tell people I died of a wasting disease and finally be rid of her embarrassment. Samuel, who had been listening while pretending to organize grain sacks, felt a chill at these words because he had begun to suspect something similar.

Lucinda’s visits had become less frequent, but when she came, she seemed disappointed rather than pleased by Catherine’s survival. The girl was losing weight, yes, but she was also growing stronger from the labor. Her arms showed muscle definition. Her breathing had become easier. She was not wasting away as Lucinda had perhaps hoped. She was adapting.

The diary entries from Lucinda Kellerman’s journal grew darker as spring turned to summer. Her clinical observations gave way to frustration than to a cold calculation that suggested she was considering more extreme measures. June 3rd, 1843. Catherine persists in her corpulence despite the rigors of labor. Weight reduction minimal.

Perhaps the rations must be further restricted. Perhaps the work must extend into the night hours. The Cartwright girl has shown marked improvement, I’m told. Why should Catherine be different? What Lucinda did not know was that Joshua had been supplementing Catherine’s meager rations with food from the quarters. Not much, just enough to keep her from the dangerous malnutrition that was making the other girls sick.

He did this at great personal risk, sharing portions that his own family needed, because he had begun to see something in Catherine that reminded him of his own daughter, a fundamental innocence, a desire to be seen as human rather than object. But there were other changes happening. Subtle shifts in the dynamic within the barn that none of them had anticipated.

Catherine and Joshua had begun to speak more freely during the long hours of work. What started as brief exchanges about tasks evolved into conversations about life, hope, and the absurdity of a world that valued some lives over others based on skin color or body shape. “Your mother would have me whipped for looking at you directly,” Joshua said.

said one afternoon as they worked together to move a broken piece of equipment. But here in this barn, working side by side, “What is the difference between us? We both bleed. We both tire. We both want freedom from the things that bind us. Catherine had never considered the parallel before. Her imprisonment was different from Joshua’s, certainly, but it was still imprisonment.

She could not leave the barn. She could not make choices about her own body or her own life. She existed only as a problem to be solved, a defect to be corrected. The first time they touched with intention rather than accident was in late June. Catherine had been lifting a sack of grain when her strength failed and she stumbled.

Joshua caught her, and for a moment they stood close enough to feel each other’s breath. Neither moved away. The air between them seemed to thicken with possibility and danger. in equal measure. “We should not,” Catherine whispered, but she did not step back. “No,” Joshua agreed. “We should not.” Yet neither of them moved.

In that barn, isolated from the world, they had created a space where the rules of plantation society seemed distant and negotiable. What happened next was inevitable, perhaps, or perhaps it was a choice they both made, knowing the consequences, but choosing connection over safety. Their relationship developed in stolen moments, always with Samuel and Daniel serving as unwitting guards, warning them if anyone approached.

What began as comfort evolved into something deeper, a genuine affection that transcended the impossible circumstances of their situation. But secrets have a way of revealing themselves, and by mid July, both Samuel and Daniel knew what was happening. Neither spoke of it directly, but they adjusted their positions to provide more privacy, created tasks that required Catherine and Joshua to work in the back corner of the barn, turned their attention elsewhere during the brief moments when the two sought each other’s company. “This will end badly,”

Samuel said to Daniel one evening after Catherine had been returned to the main house and Joshua had left for the quarters. “There is no version of this story that ends well.” Daniel, who at 16 understood the world’s cruelty in ways that should have been beyond his years, nodded slowly.

“Maybe, but maybe they deserve some happiness, even if it is brief. Maybe that is all any of us get.” Lucinda, consumed with her expanding operation of rehabilitation barns across the county, failed to notice the change in her daughter. She was too busy documenting her methods, corresponding with interested families as far away as Alabama and Georgia, and calculating the profits she might derive from offering her expertise as a consultant on reforming weward daughters.

Her journal from July 12th reveals her ambitions. Interest in the treatment methodology has exceeded all expectations. Mrs. Patricia Rutherford from Mobile has written requesting a detailed protocol. She has a daughter who insists on painting rather than focusing on suitable accomplishments. Mrs. Vivien Caldwell from Savannah inquires about outcomes, expressing concern about a daughter who has developed an unseammly interest in the family’s financial affairs.

The potential for expansion is considerable. Perhaps a published treatise on the subject, the correction of female indolence through measured labor would be an appropriate title. But while Lucinda planned her empire of cruelty, Catherine’s body was undergoing a change that had nothing to do with weight loss. By early August, she began experiencing morning sickness.

At first, she attributed it to the poor food and constant exhaustion. But when her monthly courses failed to arrive, she understood what had happened. She told Joshua first during a quiet moment when Samuel and Daniel were occupied at the far end of the barn. I am with child, she whispered, her hand instinctively moving to her stomach. Your child.

Joshua’s face went through a series of expressions. Shock, fear, and then a tenderness that made Catherine’s eyes fill with tears. But they both knew what this meant. A pregnancy would be impossible to hide. When Lucinda discovered it, the consequences would be catastrophic. They will kill you, Catherine said, her voice breaking.

My mother will have you killed for this. Perhaps all three of you to ensure no one speaks of it. Joshua took her hands in his a gesture so dangerous and so necessary that neither cared who might see. Then we have time to plan. We have time to find a way out of this. But planning required information, and information required risk.

Samuel, using his literacy and his occasional access to the plantation office, began to gather what he could. Bills of sale, property records, correspondence between plantations. He was looking for anything that might reveal the extent of Lucinda’s network, any weakness they might exploit. What he found was worse than he had imagined. Hidden in a ledger marked household expenses were entries that suggested at least four other girls had gone through Lucinda’s treatment before Catherine.

Next to each name was a final entry disposed of natural causes or transferred to family in Texas or simply resolved. What does resolved mean? Daniel asked when Samuel showed him the entries late one night. Samuel’s expression was grim. Nothing good. Nothing good at all. The pattern was clear.

Girls who did not respond to the treatment, who did not lose weight or who proved too rebellious, simply disappeared from the records. Their families received certificates of death or letters explaining they had been sent away for their own good. But there were no graves, no forwarding addresses, no trail to follow.

Catherine is in more danger than she knows, Samuel said. Even without the pregnancy, if her mother decides she has failed the treatment, she will simply be resolved. Like the others, they needed to act. But any action would require resources they did not have. Money, documents, transportation. The tools of freedom were kept carefully out of reach of those who needed them most.

It was Catherine who suggested the impossible solution. My father’s study, she said. Before he died, he kept money hidden there. Papers, too. Documents about the plantation. My mother never goes in that room. She had it locked after his death. But I know where the key is hidden. The plan they devised was born of desperation and the slim hope that the impossible might somehow become possible.

Catherine would feain increased illness from the labor, providing an excuse to be taken back to the main house more frequently. During one of these visits, she would access her father’s study and retrieve whatever money and documents she could find. With these resources, Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel would attempt to secure false freedom papers and passage north.

But every aspect of the plan required precision and luck in equal measure. The study was on the second floor of the mansion, accessible only by passing through rooms where house servants worked constantly. The key was hidden in Lucinda’s own bedroom inside a music box that had belonged to Catherine’s grandmother.

And the timing had to be perfect. Lucinda would need to be occupied elsewhere. The servants would need to be distracted, and the men in the barn would need to create an alibi for why Catherine had been allowed to leave. On August 17th, 1843, they attempted the first phase. Catherine complained of severe abdominal pain, crying out with such conviction that even Samuel, who knew she was performing, felt concerned.

The performance worked. Lucinda, irritated by the interruption to her afternoon correspondence, ordered Catherine taken to the house and confined to her room. If she is malingering, she will return to the barn tomorrow for double labor, Lucinda announced. If she is genuinely ill, Dr.

Harrison will examine her and provide appropriate treatment. The mention of a doctor terrified Catherine. Any examination would reveal her pregnancy. She had perhaps 24 hours to access the study and returned to the barn before her condition became impossible to conceal. That evening, while Lucinda attended a dinner party at a neighboring plantation, Catherine waited until the house settled into its nightly routine. She knew the patterns.

The servants would finish their evening duties by 9:00. Her mother’s personal maid would retire by 10:00, and the house would be quiet until the kitchen staff began their work at 5:00 in the morning. She had a window of 7 hours. The music box was exactly where she remembered, on Lucinda’s dressing table. Catherine’s hands shook as she opened it, wincing at the tinkling melody that seemed impossibly loud in the silent house.

The key was there, small and iron, attached to a ribbon that had faded from blue to gray. Her father’s study smelled of old leather and tobacco scents that brought back memories of a time before everything had gone wrong, before her father’s mysterious death, before her mother’s cruelty had found its full expression. Catherine allowed herself one moment of grief before focusing on the task.

The money was in a false bottom of a desk drawer, exactly where her father had shown her years ago. $300 in various bills, a fortune that could buy passage north and perhaps a new start. But it was the documents she found that truly shocked her. Letters, dozens of them dating back to 1839. letters from her father to a lawyer in Philadelphia discussing his plans to free all enslaved people on the Kellerman plantation.

Letters detailing his growing horror at the institution of slavery, his moral awakening, his determination to act on his conscience regardless of the social and financial consequences. And one final letter unsealed addressed to Catherine herself. My dearest daughter, if you are reading this, then I have failed to find the courage I needed in life and perhaps have found it only in death.

Your mother will tell you I died of heart failure, and perhaps in a sense, I did. My heart failed to be brave enough to stand against the evil I have participated in for so long. I cannot free those I have enslaved while I live, for your mother will use every legal means to stop me. But I can ensure that upon my death, the means for their freedom exists.

The money in this drawer is for you. But I hope you will use it as I could not to help those who deserve freedom gain it. Forgive me for my cowardice. Forgive me for leaving you alone with your mother’s cruelty. You deserved a better father. They deserved a better owner. I deserved a better soul.

Catherine stood in the dark study, her father’s words blurring through her tears. He had not died of heart failure. He had taken his own life, overwhelmed by guilt and the impossibility of changing the system he had benefited from. And Lucinda had hidden this truth, burned the letter he had left, and locked away any evidence of his transformation.

She took the money and the letters. But she also found something else. Her father’s will, never probated, never executed. in it. He left the plantation not to Lucinda, but to Catherine, with explicit instructions that all enslaved people were to be manumitted upon his death. Lucinda had hidden this document, continuing to operate the plantation, as if she had inherited it legitimately, forging her dead husband’s signature on documents that maintained her control.

This was the leverage they needed. This was proof that could destroy Lucinda’s authority, that could challenge the very foundation of her power. But using it would require access to the legal system, to lawyers and courts, that would never listen to an enslaved man or an obese daughter deemed incompetent by her mother.

Catherine returned to her room just as the sky began to lighten. She hid the documents and money in the lining of a winter coat that hung in her wardrobe, knowing Lucinda would never search there during the summer months. The next morning, she declared herself recovered and ready to return to the barn.

Lucinda, suspicious but unable to prove malingering, agreed, but with a warning that chilled Catherine to her core. Dr. Harrison will visit the barn tomorrow to assess your physical condition. Lucinda announced he has expressed concern that the labor may be too strenuous. I have assured him that you are thriving under this regimen, and I expect you to confirm this.

Any suggestion otherwise will result in consequences you will not enjoy. The doctor’s visit meant discovery. It meant the end of everything. They had perhaps 24 hours to act. When Catherine returned to the barn and revealed what she had found, the four of them understood they had crossed a threshold.

They possessed tools that could challenge Lucinda’s power. But using those tools would require escaping the plantation, reaching authorities who might listen, and surviving long enough to tell their story. “We leave tonight,” Joshua said, his voice carrying a certainty that did not match their desperate situation. “All four of us.

We take the money, the documents, and we run. They will hunt us,” Samuel warned. Every slave patrol in Mississippi will be looking for three escaped enslaved men and a white woman. We will not make it 10 m. But Catherine had an idea. Born from years of observing her mother’s careful manipulation of appearances. We will not be running. We will be traveling.

I will be a widow traveling with my servants to visit family in Kentucky. The money will pay for travel documents from a forger in Nachez. My father’s letters will prove my identity if questioned. We just need to reach the river and book passage on a steamboat heading north. It was a plan with a thousand ways to fail, but it was the only plan they had.

The preparation for their escape consumed the remaining daylight hours. Each of them had tasks that had to be completed without raising suspicion. A delicate dance of normaly performed over a foundation of terror. Samuel’s role was the most dangerous. He would need to enter Nachez after dark and locate a forger known only as Crawford, a free black man who operated out of a warehouse near the riverfront.

The forger’s services were expensive, and finding him required navigating a city that became increasingly hostile to any black person after sunset. Samuel would carry $50 of Catherine’s money, enough to purchase basic travel documents, but not so much that losing it would doom the entire plan. Joshua focused on gathering supplies they would need for the journey, food that would not spoil, clothing appropriate for travel, and most importantly, weapons.

He managed to acquire two knives from the plantation’s tool shed, hiding them in the barn’s rafters, where no casual inspection would find them. They were poor weapons against rifles, but they were something. Daniel’s task was to create an alibi. He would remain at the barn after the others left, maintaining the appearance that Catherine was still confined there.

In the morning, when Lucinda arrived for her inspection and found Catherine gone, Daniel would claim she had escaped during the night, overpowering him and fleeing alone. It was a story that would earn him punishment, possibly severe punishment, but it would buy the others time before the alarm was raised.

The 16-year-old accepted this role with a somnity that broke Catherine’s heart. I will say she threatened me with a tool, Daniel said, working out the details of his story. That she was crazed, that I feared for my life. They will believe a white woman could frighten me. They will believe I am a coward.

Let them believe it. Catherine spent the afternoon writing letters. One to her father, though he would never read it, telling him that she had found his hidden will and understood his final act. One to Daniel, thanking him for his sacrifice and promising that if she survived, she would return for him, and one to her mother, though this one she did not plan to send.

In it, she detailed every cruelty, every humiliation, every moment of her 19 years when Lucinda had chosen appearance over love, control over compassion. “I want her to know,” Catherine said as she sealed this final letter. “Even if we fail, even if they catch us and kill us, I want her to know that I saw her for what she truly is. Not a mother, not even a person, just an empty shell wrapped in expensive fabric, mistaking cruelty for strength.

Just when we thought we’d seen it all, the horror in Mississippi intensifies. If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries. Hit that like button to support our content, and don’t forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this. Let’s discover together what happens next.

because what they found waiting for them in Nachez would change everything. Samuel left for Nachez as the sun set, slipping away from the plantation with the practiced ease of someone who had learned to move through the world invisibly. The 8-mile journey would take him 3 hours on foot, following paths that avoided the main roads and the patrols that watched them.

In the barn, Catherine, Joshua, and Daniel waited. The silence was oppressive, each minute stretching into something that felt like hours. They had done everything they could to prepare, but preparation could not account for the thousand variables beyond their control. What if Samuel could not find the forger? What if the documents were not convincing? What if Lucinda decided to visit the barn unexpectedly? It was during this waiting that Joshua finally spoke of the thing they had all been avoiding. If we are caught, they will

kill me. Samuel and Daniel too. They will make examples of us. But you, Catherine, they might let you live. If it comes to that, if we are cornered, you must deny everything. Say we kidnapped you, forced you to help us. Save yourself. Catherine’s response was immediate and fierce. I will not. We survived together, or we failed together.

I have spent my entire life being told what to do, who to be, how to exist for the comfort of others. This is the first choice that is truly mine. I choose you. I choose this. Whatever comes. The words hung between them, a declaration and a goodbye in equal measure. Joshua pulled her close and they stood together in the darkness, feeling the weight of the impossible choice they had made.

Daniel, watching from his position near the door, felt tears he could not fully explain. He was witnessing something that should not exist in their world. Genuine love across a divide that the entire social structure was designed to prevent. It was beautiful and terrible like watching flowers bloom in a burning building. Samuel returned just before midnight and the relief on his face told them he had succeeded before he spoke a word.

Crawford sends his regards, he said, producing a packet of documents from inside his shirt. travel papers for Mrs. Katherine Kellerman widow traveling with three servants to Louisville, Kentucky. He included letters of introduction to a hotel in Nachez and a bill of passage for the steamboat.

It cost every penny of the $50, but he does good work. The papers will pass inspection unless someone looks too closely. They examined the documents by candle light. The forgery was excellent, complete with official looking seals and signatures that would mean nothing to most inspectors, but would create the appearance of legitimacy.

Catherine was listed as the widow of James Kellerman, her fictional husband, who had died of yellow fever in New Orleans. Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel, were listed as her property, valued at $3,000 total, being transported north for sale to settle her late husband’s debts. The irony of the papers was not lost on any of them.

To travel as free people would draw immediate suspicion, but to travel as owner and property, they could move through Mississippi’s checkpoints with relative ease. The system that enslaved them would be the very tool of their escape. We leave in 2 hours, Catherine decided. The roads will be quietest between 2 and 4 in the morning.

We walk to Nachez, staying off the main road. At dawn, we present ourselves at the steamboat office as travelers who arrived late and seek passage on the earliest boat heading north. The plan was sound, but as they prepared to leave, Daniel’s voice stopped them. Miss Catherine, there is something you should know, something I seen but did not speak of until now.

They turned to him and the boy’s face showed a fear that went beyond their immediate danger. The other girls, Daniel said slowly. The ones in the barns on other plantations. I was told to deliver grain to the Cartwright place last week. The barn there where Miss Rebecca was kept, it was empty. Not just empty of her, but cleaned.

Scrubbed clean like someone was erasing evidence. I asked one of the cartwright workers what happened to the girl. He would not say, but he looked at me with such pity. That kind of look, it means only one thing. The implications settled over them like a shroud. Rebecca Cartwright, the first of the other girls to undergo Lucinda’s treatment, was gone, not transferred, not sent away.

Gone in a way that required a barn to be scrubbed clean of evidence. How many? Catherine whispered. How many others? I do not know for certain, Daniel admitted. But I seen three barns that have been emptied and cleaned. Cartwright, Singleton, and Witfield. All of them started after your mother visited.

All of them ended the same way. Catherine felt bile rise in her throat. Her mother had not just been experimenting on her. She had created a system that was murdering young women across the county, all in the name of physical perfection and social acceptability. and the families desperate to correct their daughter’s perceived flaws had been complicit in their deaths.

“We cannot just save ourselves,” Catherine said, her voice shaking with rage and grief. “We have to expose this, all of it, the treatments, the deaths, everything.” But Joshua shook his head, his expression pained. “Catherine, if we try to expose this before we are safe, we will die before anyone listens. We have to survive first.

We have to reach people who have the power to investigate. Then and only then can we bring justice. He was right and Catherine knew it. But the knowledge that they were leaving Daniel behind that other girls might be suffering even as they escaped made her feel complicit in the very evil she sought to destroy. They gathered their meager supplies, the documents, the remaining money, the knives, and a small amount of food.

Catherine took one last item, the letter she had written to her mother. She would not send it, but she would keep it, a record of everything Lucinda had done. The goodbye to Daniel was brief, because anything longer would have broken them all. The boys stood at the barn door, and Catherine embraced him.

this child who was sacrificing his safety for theirs. I will come back for you, she promised. When we are safe, when we have the power to act, I will come back. You will not be forgotten. Daniel nodded, unable to speak. He watched as the three of them slipped into the darkness, disappearing into the grove of live oaks that had hidden so many of the barn’s secrets.

The walk to Nachez took 4 hours, not three. They moved slowly, stopping frequently to listen for patrols or other travelers. The night was moonless, which helped conceal them, but made the path treacherous. Catherine, unaccustomed to walking long distances, struggled to keep pace, but she pushed forward, driven by terror and determination in equal measure.

They reached the outskirts of Nachez just as the sky began to lighten. The city was already stirring. Early morning workers heading to the docks, shopkeepers opening their stores. Catherine used some of their precious water to clean her face and hands, trying to look like a respectable widow rather than a fugitive who had spent the night walking through the woods.

The steamboat office occupied a prominent position on the waterfront, its windows already glowing with lamplight. Inside, a cler sat behind a desk, reviewing manifests and passenger lists. He looked up as they entered, his expression shifting from professional courtesy to mild surprise, as he took in the unusual party. A young woman, clearly gentry from her dress despite its rumpled state, accompanied by three enslaved men.

Good morning, madam,” the clerk said, his voice carrying the careful neutrality of someone trained to serve the wealthy without question. “How may I assist you?” Catherine had rehearsed this moment in her mind a h 100red times, but now that it was here, her voice nearly failed her. She forced herself to meet the clark’s eyes, channeling every ounce of her mother’s imperious confidence.

I require passage to Louisville on your earliest departure, she said, placing the forged documents on the desk. My servants and I have had a difficult journey, and I wish to complete our travels with all possible speed. The cler examined the papers with professional thoroughess. Catherine’s heart hammered so violently she was certain he could hear it.

Behind her, Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel stood with heads appropriately bowed, playing their roles perfectly. “The Morning Star departs at 8:00,” the clerk said finally. “I can arrange a private cabin for you, madam, and quarters for your property in the cargo hold.” “That will be acceptable,” Catherine replied, though the word property made her stomach turn.

She counted out the money from her purse, watching the clerk’s expression remain neutral as he processed the transaction. “Welcome aboard the Morning Star, Mrs. Kellerman,” he said, handing her the tickets. “May your journey be peaceful. They had done it. In less than 3 hours, they would be on a steamboat heading north, away from Mississippi, away from Lucinda, away from the barn, and everything it represented.

” Catherine allowed herself the smallest breath of hope. But as they left the office and walked toward the dock where the morning star was being loaded, Samuel touched her arm gently. “Miss Catherine,” he whispered. “We are being watched.” She followed his gaze to a man standing near the warehouse, dressed in the rough clothing of a river worker.

But his posture was wrong, too alert, too focused on them specifically. As their eyes met, he turned and walked quickly toward the main street. “Slave catcher,” Joshua breathed. “He recognized something. We need to board immediately.” They hurried toward the gang plank, but moving quickly drew attention. Other workers began to notice their conversations pausing as the unusual group passed.

Catherine felt the weight of scrutiny, the questions forming in minds around them. The Morning Stars captain stood at the top of the gang plank, checking passengers against his manifest. He was an older man with a weathered face that had seen decades of river travel. His eyes narrowed as they approached. “Mrs. Kellerman,” he asked, examining her ticket.

“You are traveling alone with three male servants.” “My husband recently passed,” Catherine said, her voice steady despite her terror. I am returning to family in Kentucky. These men are being transported for sale to settle debts. The captain’s gaze moved to Joshua, then Samuel, then Daniel. Something flickered in his expression, a suspicion that Catherine could not identify, but could certainly feel.

Bored quickly, he said finally. We depart in 1 hour. They climbed the gang plank, and Catherine did not allow herself to look back at Natchez until they reached the deck. When she did, her blood froze. The man who had been watching them was now speaking urgently to two others, one of whom was mounted on horseback. The rider turned his horse and galloped toward the road that led to the plantations.

“They are going to alert my mother,” Catherine said. “We have 1 hour before she arrives with proof that I am not a widow, that these papers are forged, that we are fugitives.” Joshua’s jaw tightened. Then we pray the captain values his schedule more than he values helping a plantation mistress. They were shown to Catherine’s cabin, a small but clean room with a single bed and a port hole overlooking the river.

Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel were directed to the cargo hold, but the captain’s mate who escorted them seemed distracted, allowing them to linger near Catherine’s cabin longer than protocol would normally permit. Something is wrong, Samuel said quietly. The crew knows something. I can see it in how they look at us.

Time crawled. Catherine watched through the port hole as cargo was loaded as passengers boarded as the sun climbed higher in the sky. Every minute brought them closer to departure, but also closer to discovery. At 7:30, a commotion on the dock drew her attention. Lucinda had arrived, and she had not come alone.

Behind her carriage were three men on horseback, including the county sheriff and a group of plantation workers armed with rifles. Catherine’s mother descended from the carriage with terrible grace, her face a mask of cold fury. She approached the captain, and though Catherine could not hear the conversation, she could see her mother’s gestures, imperious and demanding. The captain shook his head.

Lucinda’s voice rose, carrying across the water. That girl is my daughter, and those men are stolen property. The captain allowed Lucinda aboard, a decision that sealed their fate. Catherine heard the footsteps on the deck, the voices growing louder, and she knew their hour of hope had expired. The door to her cabin burst open.

Lucinda stood framed in the doorway, and behind her were Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel, held at gunpoint by the sheriff’s men. Did you truly believe you could escape? Lucinda’s voice was quiet, more terrifying than if she had screamed. Did you think I would not know that I would not find you? Catherine stood, and for the first time in her life, she felt no fear of her mother. Only rage.

I found father’s will. I know what you did. You stole the plantation. You forged documents. You built your empire on lies and murder. Lucinda’s expression did not change. Your father was a weak man who would have destroyed everything our family built. I did what was necessary. You killed those girls, Catherine said.

Rebecca, Emma, Sarah, how many others? How many daughters died in those barns while you documented their suffering like a scientist studying insects? For the first time, something flickered in Lucinda’s eyes. “Not remorse, recognition that Catherine knew too much. The treatment was sound,” Lucinda said coldly.

“Some subjects simply lacked the constitution to survive it. Their families understood. They were grateful for my discretion in disposing of the evidence. The casual admission of murder, the complete absence of conscience was more chilling than any threat.” Catherine understood then that her mother was not merely cruel. She was something beyond human feeling, a void wrapped in expensive silk.

“You will return with me,” Lucinda continued. “These men will be hanged for theft and assault. The documents you stole will be burned, and you will complete your treatment because you carry evidence of your shame in your very body.” She knew somehow. Lucinda knew about the pregnancy. “Dr. Harrison examined your room this morning,” Lucinda said, reading Catherine’s expression.

“He found certain evidence that suggested your condition. He confirmed my suspicions. So you see, my dear daughter, your situation is far worse than simple disobedience.” Joshua lunged forward, but the sheriff’s man struck him with a rifle butt, driving him to his knees. Blood ran from a cut above his eye. Stop!” Catherine screamed. “I will go with you.

Just do not hurt them.” “Oh, they will be hurt,” Lucinda said. “They will be made examples.” “But first they will tell me who else knows about your father’s will. Who else has seen these documents?” “It was Samuel who spoke,” his voice clear despite his terror. Many people know. We sent copies to lawyers in Philadelphia, to abolitionists in Boston, to newspapers in New York.

Even if you kill us, even if you destroy Catherine, the truth is already spreading. It was a lie, a desperate bluff. But it was delivered with such conviction that Lucinda’s certainty wavered for the first time. “You are illiterate slaves,” she said. But her voice carried a thread of doubt. “You could not have. I can read and write better than most white men in this county,” Samuel interrupted.

And I spent 3 weeks copying every document in your office while you planned your empire of torture. Every forgery, every false death certificate, every letter arranging the disposal of bodies, it is all documented, all sent north, all waiting to be published. It was not true. But in that moment, watching her mother’s face transform from certainty to fear, Catherine understood what Samuel was doing.

He was buying time, creating doubt, forcing Lucinda to consider consequences beyond her immediate control. The sheriff stepped forward, his expression troubled. Mrs. Kellerman, if there is evidence of wrongdoing, if documents have been sent to authorities, “There are no documents.” Lucinda snapped. This slave is lying to save his worthless life.

But Catherine saw the calculation in her mother’s eyes. Lucinda was weighing risks, considering possibilities. If even a fraction of Samuel’s claim was true, exposure would destroy not just her reputation, but her freedom. Murder could be concealed in Mississippi among the cooperative elite. But not if northern newspapers began asking questions.

Prove it, Lucinda demanded. Show me evidence these documents were sent. Samuel met her gaze steadily. The proof will arrive when the investigators do. Perhaps in weeks, perhaps in days, but it will come. The standoff held for a long moment. Then Lucinda made her decision. Sheriff, take them all into custody.

Lock them in the county jail until we can sort this matter properly. If documents exist, we will find them. If they do not, these men will hang for their lies. As they were led off the steamboat, Catherine caught Joshua’s eye. In that glance, she saw goodbye. They both understood what county jail meant. It meant torture to extract confessions.

It meant death, quick or slow, depending on Lucinda’s mood. But as they descended the gangplank, Catherine felt something shift inside her. She was 19 years old, pregnant, and about to be imprisoned by her own mother. Yet, for the first time in her life, she had made choices that were truly hers. She had loved whom she chose. She had fought for freedom.

She had witnessed courage in the face of impossible odds. The jail was a stone building that smelled of dampness and despair. They were separated immediately. Catherine was placed in a small cell with a barred window. Joshua, Samuel, and Daniel were taken to the lower level where enslaved prisoners were held.

Lucinda visited Catherine that evening. She brought no food, no comfort, only cold assessment. You have cost me considerably, Lucinda said. The sheriff has questions. Other families are nervous about their own treatments. You have created complications. Good. Catherine replied. I hope I have destroyed everything you built on cruelty. Lucinda’s smile was terrible.

You have destroyed only yourself. By tomorrow, I will have extracted confessions from those men about who helped them forge documents. By next week, they will be dead and buried in unmarked graves. and you, dear daughter, will be returned to the barn until your unfortunate condition resolves itself. Dr.

Harrison has agreed to supervise to ensure no complications arise. The implication was clear. The pregnancy would be terminated one way or another. Catherine would either survive the process or join the other girls who had been resolved. “You cannot keep doing this,” Catherine said. “Eventually, someone will notice. Someone will investigate. Who? Lucinda asked simply.

The sheriff who depends on my family’s influence. The doctors who profit from my patronage. The families who are complicit in their own daughters fates. There is no one coming to save you, Catherine. There is only me and what I decide your future holds. She left and Catherine was alone with the darkness and the weight of her failure.

3 days passed in silence. Catherine heard nothing from Joshua, Samuel, or Daniel. The guards would not answer her questions. She was fed minimally, water and bread once daily, just enough to sustain life but not comfort. On the fourth day, Daniel appeared at her cell window. His face was bruised, one eye swollen shut, but he was alive.

“Miss Catherine,” he whispered urg urgently. “Listen carefully. We do not have much time. Where are Joshua and Samuel? Catherine asked, gripping the bars. Daniel’s expression told her everything before he spoke. Joshua is gone. They took him two nights ago, said he was being transferred, but we both know what that means.

Samuel is still alive, but barely. They have been questioning him. The grief was immediate and crushing. Joshua was dead. The father of her child, the man who had shown her what courage looked like, was gone. “I am so sorry,” Daniel continued, tears streaming down his battered face. “But Samuel, before they hurt him too badly, he did something.

He really did send a letter north. Not copies of all the documents like he claimed, but one letter to an abolitionist contact in Pennsylvania. He sent it weeks ago when he first suspected what your mother was doing. He told them everything about the barns, the missing girls, all of it. Catherine’s heart stuttered with desperate hope.

Will they come? Will anyone believe him? I do not know, Daniel admitted. But Miss Catherine, you need to survive until they do. Whatever your mother plans, you need to endure it. Because if investigators come and you are dead, there is no one left to testify. You are the only witness who cannot be dismissed as a lying slave. He was right.

Her survival was no longer just about herself. It was about justice for Rebecca, Emma, Sarah, and all the others. It was about exposing the network of cruelty that Lucinda had built. “How do I survive?” Catherine asked. “Agree to everything,” Daniel said. “Tell her you will be obedient. Make her believe you are broken and wait.

” That evening when Lucinda visited, Catherine played the role Daniel had described. She wept. She begged forgiveness. She promised obedience. The performance was convincing because the tears were real, even if their source was rage rather than remorse. Lucinda, satisfied that her daughter had been properly subdued, arranged for Catherine’s return to the estate, not to the barn, but to a locked room in the mansion where Dr.

Harrison could attend to her condition discreetly. The weeks that followed were a blur of isolation and fear. Catherine’s pregnancy progressed despite the minimal food and constant stress. Dr. Harrison visited regularly, his examinations clinical and cold. He never spoke of terminating the pregnancy, but Catherine understood the plan.

She would be allowed to carry to term. Then the child would be taken, disposed of, and Catherine would be declared to have suffered a tragic stillbirth. But in late October, something changed. Dr. Harrison arrived with unusual urgency, and Catherine heard raised voices downstairs. Lucinda’s tone carried an edge of panic that Catherine had never heard before.

The next morning, Catherine was moved again, this time to a carriage bound for Nachez. No explanation was given, but the speed of the journey suggested desperation. At the county courthouse, Catherine was led into a room where two men in formal dress waited. They introduced themselves as investigators from the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society sent to examine claims made in a letter they had received from Mississippi. “Mrs.

Kellerman has been most cooperative,” one investigator said, his tone suggesting he did not believe Lucinda’s cooperation was genuine. But we require testimony from other witnesses. You are Catherine Kellerman, correct? Catherine looked at her mother, who sat rigid in her chair, her face a mask of controlled fury.

Then she looked back at the investigators and made her choice. I am, she said, and I have much to tell you. The testimony took hours. Catherine detailed everything. the barn, the forced labor, the other girls who had disappeared, her father’s hidden will, the forgeries, the murders disguised as natural deaths. The investigators took notes, asked questions, and gradually the full scope of Lucinda’s operation became clear.

When Catherine mentioned her pregnancy and Joshua’s execution, one investigator’s expression darkened. “The man was killed without trial. “My mother ordered it,” Catherine confirmed. the sheriff complied. His body was never returned. Lucinda remained silent throughout, her lawyer whispering urgently in her ear, but as the evidence mounted, her certainty crumbled.

Documents were produced. Samuel, barely alive, was brought to testify. Daniel corroborated every detail. The trial that followed became one of Mississippi’s most scandalous. Lucinda Kellerman was charged with multiple murders, forgery, and theft of property. Other plantation families who had participated in the treatments faced scrutiny.

Some fled the state, others destroyed evidence and claimed ignorance. Lucinda was convicted in January 1844 and sentenced to life imprisonment. She died in the state prison 2 years later, her body buried in an unmarked grave, her name struck from the society pages she had once dominated. Katherine gave birth to a son in February 1844.

She named him Thomas Joshua, honoring both her father and the man she had loved. Using her father’s legitimate will, she inherited the Kellerman plantation and immediately began the process of manu mission, freeing every enslaved person on the property. Samuel survived his injuries and remained on the plantation as a paid worker, helping Catherine manage the transition.

Daniel too stayed, pursuing the education that had been denied him. Together they built something unprecedented. A Mississippi plantation operated without slave labor run by people who had once been property. The barn where Catherine had been imprisoned was torn down in the spring of 1844. In the earth beneath its foundations, they found remains.

Seven sets of bones buried in shallow graves. Seven girls who had not survived Lucinda’s treatment. seven daughters whose families had chosen to accept their deaths rather than question the methods that caused them. Catherine ensured each girl was properly buried, their names recorded, their stories told, Rebecca Cartwright, Emma Singleton, Sarah Witfield, and four others whose identities took months to confirm.

Abigail Henderson, Margaret Ashworth, Virginia Thorne, and Elellanena Puit. This mystery shows us that the greatest horrors are not supernatural but human. They are born from obsession with appearance, from the devaluing of life, from systems that protect cruelty when it wears the mask of respectability. What do you think of this story? Do you believe everything was revealed? Leave your comment below.