On November 8th, 1,849, a cotton merchant named Josiah Peton was found dead in a tobacco barn outside Natchez, Mississippi. His body was discovered by his own overseer at dawn, hanging from a support beam with a noose around his neck. The local sheriff ruled it suicide within hours, noting in his report that Peton had recently suffered financial losses and appeared despondent. The case was closed.

The body was buried. Life continued. But what the sheriff didn’t investigate. What he chose not to see was that Josiah Peton’s hands were bound behind his back with hemp rope. You cannot hang yourself with your hands tied. Someone had executed him and made it looked like suicide. And that someone had done this before, many times before.

Between 1,832 and 1,863 across five southern states, at least 250 white men died under circumstances that authorities either couldn’t explain or chose not to investigate too carefully. Plantation owners, overseers, slave traders, patrollers, county sheriffs, federal marshals, wealthy merchants who profited from human bondage, all dead.

Some found hanging in barns or warehouses with their hands mysteriously bound. Others discovered drowned in shallow creeks where drowning should have been impossible. Some simply vanished without a trace, their horses found wandering, their weapons unused, their bodies never recovered. The deaths spanned three decades and covered territory from Virginia to Louisiana.

No pattern was ever officially acknowledged. No investigation ever connected them. No arrest was ever made. But buried in courthouse basement, in private letters, in plantation records, in the oral histories of formerly enslaved people, a name appears, always whispered, never written in official documents.

the name of a man who moved through the antibbellum south like smoke, who could disappear into a crowd of enslaved workers and become invisible. Who understood that the system which enslaved him had created its own vulnerabilities? Who learned to exploit those vulnerabilities with surgical precision, who killed without mercy and vanished without trace.

They called him Moses, not because he led people to freedom, though some say he did that too, but because like the biblical Moses, he was the angel of death passing through Egypt. And every firstborn son of the pharaohs fell.

The version that tells you enslaved people were helpless victims waiting for white saviors to free them. The truth is far more complex, far more violent, and far more empowering than anyone wants to admit.

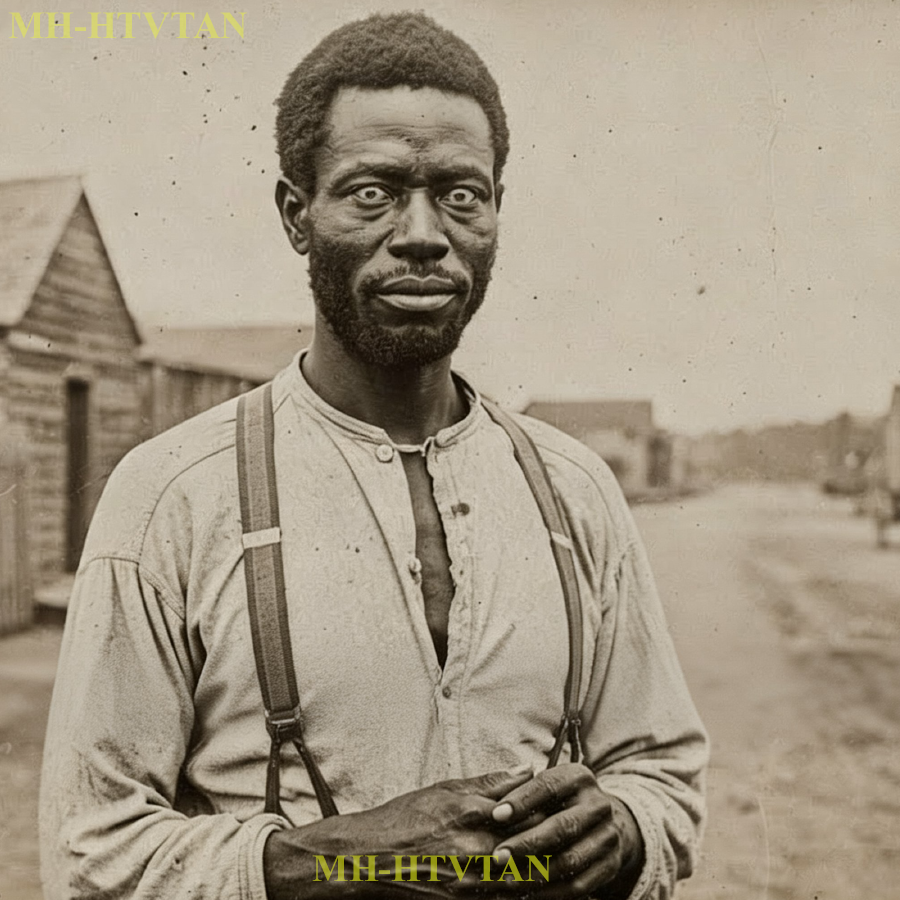

This story starts not with violence, but with a sale. August 17th, 1,832. The slave market in Richmond, Virginia. A humid morning, where the air hung thick enough to choke on, where the smell of unwashed bodies mixed with the stench of fear.

On the auction block stood a man approximately 28 years old, identified in the auctioneers’s ledger only as Daniel, prime fieldand, strong back, no defects. Some resistance noted that last phrase should have been a warning. resistance noted. But the buyer, a tobacco plantation owner named Marcus Whitfield, saw only a powerful physique and paid $950 for the man, taking him in chains to a plantation 40 mi west of Richmond.

The plantation was called Asheford. It sat on 3,200 acres of prime tobacco land worked by 180 enslaved people under the supervision of seven overseers who ruled through systematic terror. Whitfield himself rarely interfered in daily operations. He lived in the main house, managed his accounts, entertained guests, and let his overseers handle the brutal mechanics of forced labor.

He considered himself a businessman, not a slaver. He was wrong on both counts. The man purchased as Daniel arrived at Ashford on August 20th, 1,832 along with four others from the same Richmond auction. They were processed like livestock, stripped, examined for hidden injuries, assigned numbers, given rough clothing, and marched to the quarters.

a collection of wooden shacks arranged behind the work buildings where enslaved families lived in conditions that would have shamed a livestock owner. Daniel was assigned to the first gang, the highest tier of field workers reserved for the strongest men. The work was brutal. Tobacco cultivation required constant attention.

planting, weeding, pruning, topping the plants to force energy into the leaves, harvesting, hanging the leaves in curing barns, stripping, packing. The labor stretched from before sunrise to after sunset during growing season. The overseers enforced productivity through violence. A man who worked too slowly received the whip.

A man who talked back received worse. A man who tried to run and was caught received public punishment designed to destroy both body and spirit. For the first 3 months, Daniel did exactly what was expected. He worked in silence. He kept his eyes down. He ate his rations of cornmeal and fatback. He slept in his assigned space in the quarters.

He showed no emotion, no personality, nothing that would make him memorable. To the overseers, he was just another body in the fields, indistinguishable from the dozens of other men bent over the tobacco rose. But Daniel was doing something the overseers couldn’t see. He was learning. Every day he memorized more. The layout of the plantation, the blind spots in the patrol routes, the schedules the overseers followed, which men drank heavily at night and which stayed alert, where the property boundaries lay, which roads led where, how the local slave

patrols operated, where the dogs were kept. He learned the sounds of Asheford, the routine noises that signaled normal operations versus the urgent sounds that meant trouble. He learned to move without making sound, to be present without being noticed, to fade into the background of plantation life while observing everything. And he waited.

On November 23rd, 1,832, exactly 3 months after Daniel’s arrival, the first overseer died. His name was William Cobb, and he’d worked at Ashford for six years. He was known for carrying a hickory cane that he used to strike workers across the back of the legs, a punishment that caused intense pain without marking the skin visibly enough to reduce a slave’s value at auction.

Cobb’s body was found in one of the tobacco curing barns at dawn. He’d been working late the previous night, checking the temperature and humidity levels in the barn, where thousands of tobacco leaves hung drying on racks. The work required someone to stay through the night adjusting ventilation, maintaining the delicate balance that produced quality tobacco.

According to the report filed by Marcus Whitfield with the county authorities, Cobb had apparently fallen from one of the upper racks where he’d been inspecting leaves. The fall, approximately 15 ft, had broken his neck. His body lay on the dirt floor of the barn, his hickory cane beside him, his lantern still burning on a nearby hook.

The plantation physician, a doctor named Hastings, who serviced several estates in the area, examined the body and confirmed death by broken neck consistent with a fall. There were some bruises on Cobb’s arms and torso, but Hastings attributed these to the impact. No one questioned his conclusion. Falls happened. Barnes were dangerous places in the dark.

Men lost their footing. Cobb was buried in the plantation cemetery, and Whitfield hired a replacement overseer within a week. What Hastings didn’t note, what he chose not to investigate too carefully, was that the bruises on Cobb’s arms were finger-shaped, the kind of marks that come from someone gripping you with tremendous force, the kind that appear when someone holds you down.

and he didn’t examine Cobb’s pockets where a small piece of cloth had been stuffed, a piece torn from a slave’s shirt. A message, though no one understood it yet. For 4 months, nothing unusual happened at Ashford. The new overseer, a man named Peterson, settled into his duties. The tobacco was harvested and cured and sold.

Whitfield made excellent profits that season. Life continued in its brutal routine. Then on March 14th, 1,833, Peterson disappeared. He’d left the main house after dinner, telling the other overseers he was going to check the quarters before turning in for the night. He carried a lantern and a pistol, standard equipment. He never came back.

A search party formed at dawn when Peterson failed to appear for breakfast. They combed the plantation systematically, the quarters, the fields, the woods, the tobacco barns, the roads. They questioned every enslaved person they encountered. They brought out dogs to track his scent. The dogs followed a trail from the main house toward the quarters, then lost it near one of the irrigation ditches that ran through the property.

The search continued for 3 days. They dragged the ditches. They searched every building twice. They sent riders to neighboring plantations asking if anyone had seen him. Nothing. Petersonen had vanished as completely as if he’d never existed. His pistol was never found. His lantern was never found. His body was never found.

Whitfield reported the disappearance to the county sheriff, who conducted his own investigation and reached no conclusions. Some suggested Peterson had run up gambling debts and fled. Others thought he’d been drunk and fallen into one of the deeper ditches and drowned, his body carried away by water flow.

A few whispered that one of the slaves had killed him, but without evidence that theory led nowhere. The case went unsolved. Whitfield hired another replacement, a man named Dutch, who’d worked on plantations in South Carolina and came with strong recommendations. But in the slave quarters, in the conversations that happened after dark in languages and codes the overseers couldn’t understand, people were talking.

A woman named Sarah mentioned she’d seen Daniel returning to his cabin late one night, his clothes wet around the time Peterson had disappeared. A man named Joseph said he’d noticed Daniel watching Petersonen for days before the disappearance, studying his routines with unsettling focus. None of them reported these observations to the authorities.

To do so would have meant torture and likely death for themselves, but a quiet understanding began spreading through the enslaved community at Ashford. Someone was fighting back, and that someone was careful, patient, methodical. On June 2nd, 1,833, Dutch died in broad daylight. He’d been supervising a work gang in one of the distant tobacco fields.

a quarter mile from the main buildings. It was midm morning, the sun already fierce, the air thick with humidity. Dutch was standing at the edge of the field, watching the workers move through the rose when he suddenly collapsed. The workers closest to him saw him grab his throat, his face turning red, then purple.

He fell to his knees, gasping, clawing at his neck. Within 2 minutes, he was dead. The plantation physician was summoned immediately. Hastings examined Dutch’s body right there in the field with workers standing in a loose circle watching. Hastings concluded it was heart failure likely brought on by the heat. Dutch had been overweight.

He noted he’d probably been drinking. These things happened. But one of the enslaved workers, a young man named Thomas, noticed something the physician either missed or chose to ignore. Dutch’s water flask, which he carried on his belt, smelled wrong, not like water, like something bitter, something that shouldn’t be there. Thomas said nothing.

He went back to work. But that night he told others what he’d observed, and the understanding deepened. This wasn’t random. This wasn’t accidents. This was war. A war being waged by one man who’d learned that the system which enslaved him could be turned against itself. who understood that in a world built on violence, violence could flow in both directions.

Who discovered that masters who saw enslaved people as invisible had made themselves vulnerable to an invisible threat. Three overseers dead in 7 months. And Daniel, quiet Daniel, who never caused trouble, who worked without complaint, who seemed to disappear into the background of plantation life, was still there, still working, still watching, still waiting for the next opportunity.

Marcus Whitfield was beginning to feel afraid. He couldn’t articulate why the deaths could be explained as accidents and misfortune. But something in his gut told him there was a pattern. Something was happening on his plantation that he didn’t understand and couldn’t control. He began carrying a loaded pistol everywhere. He doubled the patrols.

He ordered the overseers to work in pairs when possible. And on August 12th, 1,833, exactly 1 year after purchasing Daniel, Whitfield made a decision. He called his estate manager and ordered Daniel sold. He didn’t explain his reasoning. He simply wanted the man gone. Better to be rid of him at a loss than keep him and risk whatever instinct was screaming at Whitfield that this particular slave was dangerous.

On August 20th, 1,833, Daniel was taken in chains back to Richmond and sold at auction for $875. The buyer was a cotton plantation owner from North Carolina named Benjamin Garrett who operated a massive estate called Thornhill near the town of Edon. Garrett had come to Richmond specifically looking for strong field hands. Cotton was booming.

The demand from textile mills in England seemed endless. A man who could expand his acorage and increase production stood to make a fortune. Garrett examined Daniel on the auction block, checked his teeth, felt his arms and shoulders, asked him to walk, to bend, to demonstrate his strength. Daniel complied without expression, his face a mask of dosile obedience.

Garrett saw what he wanted to see, a strong worker, no obvious defects, worth the investment. The chains went back on. Daniel was loaded into a wagon with six other purchases and transported 200 m south to Thornhill, a journey that took 5 days through late summer heat. Thornhill was larger than Asheford, nearly 5,000 acres of cotton fields worked by 280 enslaved people, supervised by nine overseers.

The operation was more sophisticated, more profitable, and more brutal. Cotton cultivation required different skills than tobacco, but the same backbreaking labor. Planting in spring, chopping weeds through summer, picking in fall, your hands bleeding from the sharp bowls, your back screaming from bending thousands of times per day, jinning and bailing the harvest, then starting over.

Daniel arrived on August 25th, 1,833. He was assigned to the second gang of field workers. He received his clothing, his tools, his sleeping space in the quarters. And for two months, he did exactly what he’d done at Ashford. He worked in silence. He learned the layout. He memorized the routines. He identified the vulnerabilities in Thornhill security.

He studied the overseers, learning which ones were cruel, which were merely indifferent, which represented the greatest threat to the people suffering around him. And he chose his targets carefully. On October 31st, 1,833, an overseer named Richard Sloan was found dead in his bed. Sloan had been one of the crulest men at Thornhill, known for his creative punishments.

He’d once forced a man to dig his own grave, then stand in it for 12 hours as punishment for attempting to run. He’d beaten women who were pregnant. He’d separated families as punishment for minor infractions. The enslaved community at Thornhill feared and hated him in equal measure. Sloan’s body was discovered by another overseer when he failed to appear for morning roll call.

He was lying in his bed in the overseer’s quarters, a building where six of Thornhill’s supervisors lived. His face was purple, his tongue protruded, his eyes were bulged and bloodshot. The plantation physician, a different doctor named Mand, examined the body and ruled it death by natural causes, possibly a stroke or seizure during sleep.

But Sloan’s pillow showed signs of pressure, deep creases, as if something had been pressed down hard over his face, and his door, which should have been locked from the inside, was unlocked. Someone had entered his room while he slept. Someone had suffocated him with his own pillow. Someone had then arranged the scene to look natural and left without being seen or heard by any of the other five overseers sleeping in the same building.

2 months later, on December 28th, 1,833, another overseer named Francis Drummond vanished. He’d been riding the property boundary on horseback, conducting his regular patrol. His horse returned without him at dusk, the rains dragging the saddle empty. Search parties found nothing, no body, no signs of struggle, no indication of what had happened.

Drummond simply ceased to exist. In February 1834, an overseer named Caleb Thornton died when his horse allegedly threw him during morning rounds. His neck broke in the fall. But experienced horsemen noted that Thornton’s horse was gentle and well-trained. It didn’t make sense for such an animal to suddenly buck violently enough to kill its rider.

And there were marks on Thornton’s saddle girth, cuts that looked deliberate, as if someone had partially severed the leather so it would fail under stress. Three overseers dead or missing in 4 months. Benjamin Garrett was terrified. He couldn’t understand what was happening. He increased security.

He armed all the overseers with pistols and rifles. He installed additional patrols. He questioned the enslaved workers brutally, looking for any hint of conspiracy or rebellion. He found nothing. No one admitted seeing anything. No one offered information. The wall of silence was absolute. And so on April 3rd, 1,834, exactly as Marcus Whitfield had done the previous year, Garrett decided to sell Daniel.

He couldn’t prove Daniel was involved in the deaths. He couldn’t even articulate why he suspected him, but something about this particular slave made Garrett deeply uncomfortable. The way Daniel seemed to observe everything, the way he moved with a confidence that didn’t match his supposed status, the way other enslaved people watched him when they thought no one was looking.

Daniel was sold again, this time to a rice plantation in South Carolina for $900. Then 6 months later to another cotton estate in Georgia for $850. Then to a sugar plantation in Louisiana for $925. Then back east to a tobacco farm in Virginia for $800. Between $1,834 and $1,840, Daniel or whatever his real name was was sold 12 times.

12 different plantations across five states. And at every single location, within months of his arrival, white men involved in the slave system began dying. The pattern was always the same. Daniel would arrive. He would work quietly for several weeks or months, learning the terrain, studying the people, identifying his targets.

Then the deaths would start. Overseers found dead in circumstances that could be explained as accidents or natural causes, but which upon closer examination showed signs of something more sinister. Slave catchers who disappeared while tracking runaways. Plantation managers who drowned in water that shouldn’t have been deep enough.

County officials who died in their sleep from unexplained causes. And always Daniel would be there, quiet, unremarkable, invisible in plain sight, until the plantation owner’s nerve broke and he sold Daniel to someone else, passing the problem along, never quite admitting what he suspected, but unable to live with the fear.

The enslaved communities at each plantation recognized what was happening. They understood that Daniel wasn’t just killing randomly. He was executing a very specific campaign. He targeted the crulest overseers first, the men who beat women, who separated families, who invented creative tortures, who took sadistic pleasure in their power.

Then he moved to slave catchers, the professional hunters who tracked down runaways with dogs and guns and brought them back for public punishment. Then plantation managers who ran the day-to-day operations. Then merchants and traders who profited from the system. He was systematic, patient. He never took unnecessary risks. He never killed unless the opportunity was perfect.

And he never ever left evidence that could be traced back to him with certainty. Stories began spreading through the underground networks that connected enslaved people across the South. Stories about a man who moved from plantation to plantation, leaving dead white men in his wake. A man who couldn’t be caught or stopped. A man who represented something the enslaved population desperately needed to believe in.

The possibility of resistance, the possibility of justice, the possibility that they weren’t helpless. They gave him names. Moses, the angel, the shadow, the ghost. Different communities called him different things, but the meaning was always the same. He was death to slaveholders. He was hope to the enslaved. By 1840, plantation owners across the deep south were starting to notice a disturbing pattern.

They met in private clubs and drawing rooms, drinking brandy and smoking cigars, discussing the problem in hushed voices. Too many overseers were dying. Too many slave catchers were disappearing. The deaths seemed to cluster around certain properties, then move to new locations following no predictable pattern. Some of them started comparing notes.

They pulled out ledgers and auction records. They traced sales and transfers. And slowly, a few of the sharper mines began to see something that made their blood run cold. There was a slave who’d been sold an unusual number of times. A man who appeared in the records of multiple plantations where unexplained deaths had occurred.

A fieldand who seemed unremarkable in every way except for one thing. Wherever he went, white men died. But they couldn’t prove it. They had no witnesses, no confession, no physical evidence, just a pattern that might be coincidence. A series of accidents and natural deaths that happened to cluster around one particular individual’s movements.

In January 1841, a group of wealthy planters in Charleston, South Carolina, pulled resources and hired a private investigator, a former Pinkerton detective named Amos Fairchild, who specialized in difficult cases. They gave him access to plantation records, auction ledgers, death certificates, and court documents going back a decade. They told him to find the pattern, to identify who was responsible for the killings, and to help them stop it.

Fairchild was methodical. He spent four months reviewing documents, interviewing plantation owners, visiting properties where deaths had occurred. He traveled from Virginia to Louisiana following a trail of corpses and suspicious circumstances. And in May 1841, he submitted his report. The report was 47 pages long.

It documented 89 deaths occurring between August 1,832 and March 1,841 that fit a specific profile. White men involved in the slave system, deaths that appeared accidental or natural, but showed subtle inconsistencies occurring at properties where a specific enslaved man had been present or nearby. Fairchild had traced this individual through 12 sales, 14 plantations, and five states.

He’d interviewed 17 different plantation owners who’d all expressed similar unease about this particular slave. He documented the progression of deaths following this man’s movements with eerie precision. Fairchild’s conclusion was stark. Gentlemen, you have been harboring a serial killer, an enslaved man of remarkable intelligence and patience who has been systematically murdering white men for nearly a decade without being caught.

Based on the evidence, I estimate his actual death toll may exceed 100 individuals. He operates by learning the vulnerabilities of each property, identifying cruel or vulnerable targets, and striking when conditions are optimal. He makes deaths look accidental. He leaves minimal evidence. And he’s learned that being sold from plantation to plantation actually protects him by preventing any single authority from seeing the full pattern.

The report recommended immediate action. Locate the individual currently identified in records as Daniel, though Fairchild suspected this wasn’t his real name. Arrest him. Interrogate him. execute him publicly as a warning to other enslaved people who might consider resistance. But there was a problem. By the time Fairchild submitted his report in May 1841, Daniel had disappeared again.

His last recorded sale had been in March 1841 to a cotton plantation in Alabama. But when authorities went to that plantation to arrest him, he was gone. The plantation owner said Daniel had been there for 3 weeks, then simply vanished. One morning, never returned from the fields. A search party found nothing.

Fairchild organized a massive manhunt. He brought in slave patrols from three states. He offered a reward of $1,000, an enormous sum, for information leading to Daniel’s capture. He distributed descriptions to every plantation, every sheriff, every slave catcher in the south. For 6 months, nothing, no sightings, no leads.

Daniel had vanished into the landscape as if he’d never existed. Then in November 1841, a slave trader named Horus Bentley was found dead in a warehouse in Mobile, Alabama, where he kept enslaved people before shipping them to auction. Bentley had been strangled with a length of chain. The warehouse had been locked from the inside.

There were no witnesses, and 20 enslaved people who’d been shackled in the warehouse were found unchained and gone, vanished into the night. One week later, a plantation overseer in Mississippi died in his sleep, suffocated with his own pillow. Two weeks after that, a slave catcher in Louisiana drowned in a bayou in water 18 in deep.

The killings had resumed and the message was clear. The manhunt had failed. Daniel wasn’t hiding. He was still hunting, still executing his private war, still moving through the south like a ghost that couldn’t be captured or killed. Between 1,842 and 1,850, the situation became more complex and more terrifying for those who profited from slavery.

Daniel, or whatever name he was using at any given time, seemed to have evolved his methods. He was no longer staying at plantations long enough to be sold through legitimate channels. Instead, he was moving through the south using the very networks that enslaved people had created to survive. The Underground Railroad is famous for helping people escape north to freedom.

But there were other networks, less discussed in history books, that served different purposes. networks that passed information, that warned of slave catchers in an area that identified which plantation owners were considering selling families apart, that tracked which overseers were particularly brutal.

Daniel had plugged into these networks, and they protected him the way a body protects its immune system. He would appear at a plantation, having walked there, or been smuggled in with legitimate purchases. He would work for a few weeks invisible among the dozens or hundreds of other enslaved workers. He would identify targets.

He would strike and then he would vanish, moving along routes that no white person understood or could trace, sheltered by communities that saw him not as a murderer, but as an instrument of justice. The deaths during this period became more brazen. In March 1842, a notorious slave catcher named James Harrove was found dead in his own home in Vixsburg, Mississippi.

Someone had entered while he slept, slit his throat with surgical precision, and left without waking his wife sleeping beside him. The killer had left something on Harrove’s chest, a small wooden cross, the kind enslaved people carved, a signature, a message. In July 1843, a plantation owner named Silas Blackwood, known for his exceptional cruelty, was killed in broad daylight at a county fair in Georgia.

Blackwood was walking through the crowded fairgrounds when he suddenly collapsed, a knife wound in his back, so precisely placed it had pierced his heart instantly. By the time people realized what had happened, the killer had disappeared into the crowd. Witnesses gave dozens of different descriptions. None were useful. It was as if the attacker had been invisible.

In December 1844, an entire slave patrol, four armed men on horseback, disappeared while tracking a runaway in the swamps of Louisiana. Their horses were found 3 days later, wandering loose. Their bodies were never recovered. The swamps had swallowed them completely. Authorities were desperate. The manhunt that had failed in 1841 was renewed with greater resources.

Amos Fairchild, the detective, was hired again. This time he brought a team of trained investigators. They established a network of informants. They offered increasingly large rewards for information. They tortured enslaved people suspected of helping the killer. They executed several people publicly as warnings to others who might be protecting him. None of it worked.

The wall of silence held. Even under the most brutal interrogation, even facing death, not a single enslaved person gave up information that led to Daniel’s capture. Some died without speaking. Others gave false information that sent investigators in wrong directions. The solidarity was absolute, and it spoke to something that terrified slave owners more than the deaths themselves.

It meant their system had a fundamental vulnerability they couldn’t fix. They’d built their world on the premise that enslaved people were property, inferior, broken, incapable of organized resistance. But Daniel’s campaign proved otherwise. It proved that enslaved people could organize, could keep secrets, could wage war against their oppressors.

And if one man could kill over a 100 white men in a decade without being caught, what did that say about the security of the entire system? Plantation owners started sleeping with loaded weapons. Some built fortified bedrooms with locks and bars. Others hired private guards to patrol their homes at night. The psychological impact was profound.

These were men who’d felt invulnerable, who’d wielded absolute power over hundreds of human beings. Now they were afraid. They were looking over their shoulders. They were questioning whether the quiet slave working their fields might be the angel of death, waiting for the right moment. In 1846, something remarkable happened. A Presbyterian minister named Reverend Thomas Ashford, who owned a small plantation in South Carolina, published a letter in several southern newspapers.

The letter was titled A Confession and Warning. In it, Ashford admitted he’d been visited by someone he believed was the man they were hunting. A man who’d appeared at his plantation, worked for 2 weeks, then came to Asheford’s study late one night. According to Ashford, this man had sat across from him, calm and articulate, and explained his mission.

“He wasn’t killing randomly,” the man had said. He was executing justice. Every man he killed had committed acts of extreme cruelty. Every death was earned, and he would continue until the system of slavery ended, or he was killed, whichever came first. Ashford wrote that he’d asked the man why he was telling him this. Why reveal himself? The man had replied that Ashford was known to treat his enslaved workers relatively humanely.

That he didn’t beat them excessively, that he kept families together, that he allowed them religious instruction. I’m not here to kill you. The man had supposedly said, “I’m here to deliver a message. Change this system or more will die. The choice is yours.” Then the man had left, walking out into the night.

Ashford had been so shaken he couldn’t move for several minutes. By the time he’d gathered his courage to call for help, the visitor had vanished. Ashford ended his letter by stating he was freeing all his enslaved workers and selling his plantation. He couldn’t continue participating in a system that produced such monsters on both sides.

The letter caused a sensation. Some called Ashford insane. Others suggested he’d fabricated the story. But many plantation owners read it with a cold recognition. They understood that the fear Ashford described was real because they felt it themselves. The knowledge that someone might be watching them, judging them, planning their execution.

Meanwhile, the death toll climbed. Fairchild’s updated estimate in 1848 put the number at 187 confirmed deaths that fit the pattern with dozens more possibles. The killings were spreading geographically, too. Deaths matching the profile were now being reported from Texas to Maryland, from Tennessee to Florida.

Either Daniel had expanded his territory, or more disturbing, he’d inspired copycats. Other enslaved people were adopting his methods, targeting the crulest members of the slave system using similar tactics. The authorities couldn’t tell which deaths were Daniel’s work and which were the work of others. And that was terrifying because it meant the resistance was spreading beyond one individual.

It was becoming a movement, a method, a form of warfare that the system had no effective defense against. In 1850, the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, requiring northern states to cooperate in returning runaway slaves to their owners. The law was meant to strengthen the slave system, but it had an unintended consequence.

It drove more northerners to support the Underground Railroad. It increased sympathy for enslaved people, and it created more opportunities for resistance because it put federal officials directly in the enforcement chain. Daniel, according to later accounts from formerly enslaved people, saw this as an opportunity. Between 1,850 and 1,853, several US marshals enforcing the Fugitive Slave Act died under suspicious circumstances.

One was found dead in a Boston alley, his neck broken. Another disappeared while transporting captured runaways through Pennsylvania. A third died in his home in Ohio from what appeared to be poisoning. The federal government was now involved. This wasn’t just plantation owners losing overseers. This was US marshals being killed by what amounted to a terrorist operating across state lines.

The Justice Department assigned federal resources to the case. They coordinated with local authorities. They established a task force specifically targeting the individual or individuals responsible and they failed completely. The killings continued. The pattern persisted. The resistance grew. By 1855, the estimated death toll attributed to Daniel and possible copycats had exceeded 200.

Amos Fairchild, now in his 60s and exhausted from over a decade of failed investigations, submitted his final report. In it, he admitted defeat. This individual or these individuals have created a form of warfare that our system cannot counter. They move invisibly through populations we cannot access.

They have support networks we cannot penetrate. They strike with a patience and precision that defeats conventional law enforcement. Unless the underlying system changes, unless the institution of slavery is reformed or eliminated, these deaths will continue. We cannot protect every overseer, every slave catcher, every official.

There are simply too many potential targets and too few resources to guard them all. Fairchild’s report was suppressed. Publishing it would have admitted that the slave system was fundamentally vulnerable, that white authorities couldn’t protect white men from enslaved resistance. Such an admission would have caused panic and potentially inspired more resistance.

But privately, many plantation owners read the report and understood its implications. Some began treating their enslaved workers less harshly, hoping that moderation might protect them. Others doubled down on brutality, believing that only through overwhelming force could they maintain control. Neither approach solved the problem.

And then in 1857, something unexpected happened. The killing stopped, not gradually, but suddenly. For months, no deaths matching the profile were reported. The man they’d been hunting, the ghost who terrorized the South for a quarter century, seemed to have vanished. Some believed he’d died after 25 years of violence and constant movement.

Perhaps his body had finally given out. Perhaps he’d been killed in some remote location where his body was never found. Perhaps he’d achieved whatever goal he’d set for himself and retired. Others believed he’d escaped north, either to freedom in Canada or to continue his work in a different form.

Some whispered that he’d become a conductor on the Underground Railroad, using his skills to help others escape rather than to kill. But a few, particularly in the enslaved communities that had sheltered and protected him for decades, believed something different. They believed he was preparing for something larger. They believed he saw what was coming before anyone else did.

The nation was splitting apart. The debate over slavery had reached a crisis point. Several southern states were threatening secession if a Republican president was elected. War was coming. A war that would determine whether slavery continued or ended. And some believed that the man they called Moses was positioning himself for that war, preparing to continue his mission on a much larger scale.

On November 6th, 1,860, Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States. Within weeks, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Six more states followed. In April 1861, Confederate forces fired on Fort Sumpter and the Civil War began. Four years of slaughter followed. Over 600,000 men died in battles from Gettysburg to Shiloh, from Antitum to Chikamaga.

The South was devastated. The institution of slavery was destroyed. And in the chaos of war, in the massive movement of armies and refugees and escaped slaves, individual deaths became impossible to track. But there are stories, fragmentaryary accounts from former slaves interviewed decades later, Confederate military correspondents preserved in archives, newspaper reports from occupied territories.

And these stories suggest that during the Civil War, the pattern continued. Confederate officers dying in their tents from unexplained causes. Slave catchers operating behind Confederate lines found dead in circumstances that defied explanation. Plantation owners who’d fled Union advances but stayed in southern territory dying despite being far from battle lines.

The deaths were attributed to the chaos of war, to guerilla fighters, to deserters and outlaws. No one connected them to a pattern because everyone was too busy surviving the largest war the nation had ever fought. In 1863, a Union officer named Colonel William Brennan wrote a dispatch from occupied New Orleans that was filed away in military archives and forgotten for over a century.

The dispatch described what Brennan called a peculiar phenomenon occurring in areas of Louisiana under Union control. Confederate sympathizers, particularly former plantation owners and overseers who’d remained in occupied territory, were dying at an unusual rate. Not from combat, Brennan noted, but from accidents, illnesses, and unexplained circumstances.

It’s as if, Brennan wrote, someone is systematically eliminating those who profited most egregiously from the slave system. The colored population knows something about these deaths, but will not speak of it, even to Union officers who’ve liberated them. They smile when questioned, but offer no information. It’s the strangest conspiracy of silence I’ve ever encountered.

Similar reports came from other occupied territories. From South Carolina, where Sherman’s army was cutting through the state, leaving destruction in its wake. from Virginia, where the conflict had devastated the countryside. From Mississippi, Tennessee, Georgia, wherever Union forces established control and freed enslaved populations, unexplained deaths of former slave owners and overseers followed.

A Union chaplain named Reverend Samuel Norton interviewed dozens of freed slaves in 1864, trying to understand the phenomenon. He compiled their stories into a manuscript he titled Testimonies of the Freed. In it, multiple people referenced a figure they called by different names. The angel, the deliverer, the shadow of justice, Moses, one elderly woman named Claraara, who’d been enslaved for over 60 years, told Norton, “There was always someone watching the cruel ones, someone keeping count of their sins.

We knew that justice delayed ain’t justice denied. We knew that the Lord sends his angels in his own time. And we knew that some angels don’t carry harps, they carry vengeance. Norton pressed her for details. Who was this person? How did he operate? How had he avoided capture for so long? Claraara had smiled the way Brennan described in his dispatch and said only, “Some questions ain’t meant to be answered, Reverend.

Some mysteries serve a purpose by remaining mysterious. Let the slavers wonder. Let them fear. Let them spend the rest of their days looking over their shoulders, knowing that justice might come for them at any moment. That fear, that’s a punishment, too. Norton’s manuscript was never published during his lifetime.

It was considered too inflammatory, too likely to encourage further violence during an already violent period. but it was preserved in his personal papers and eventually donated to a university library where it sat unread for decades. The Civil War ended on April 9th, 1,865 with Lee’s surrender at Appamatics. The 13th Amendment abolished slavery.

4 million people who’d been property became legally free. The South was devastated, its economy destroyed, its social system shattered, its landscape scarred by four years of total war. In the chaos of reconstruction, tracking individual deaths became impossible. The records that had documented slave sales and movements no longer existed in any organized form.

Plantation ledgers were destroyed or abandoned. Court records were lost. The entire bureaucratic infrastructure of the slave system collapsed. And somewhere in that collapse, the man known as Daniel, as Moses, as the angel, disappeared from history. But there are fragments, clues, stories that suggest a possible ending to his story.

Though like everything else about his life, the truth remains uncertain. In the National Archives, there’s a pension application from 1,867 filed by a man identified only as Daniel Freeman, claiming service with the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first African-American units in the Union Army.

The application is unusual because the man claimed to be significantly older than typical soldiers, listing his age as approximately 63. If true, that would place his birth around 1,84, making him the right age to be the Daniel sold at Richmond in 1832. The application was denied because the man couldn’t provide documentation of his service.

Military records showed no soldier by that name in the 54th, but the rejection letter preserved with the application contains a curious note from the reviewing officer. Applicant demonstrates detailed knowledge of military campaigns in South Carolina and Georgia 1,863 to 1,865. However, his description of activities during this period do not match standard infantry operations.

He describes what sounds like reconnaissance and irregular operations behind enemy lines. No record exists of such authorization. claim denied. Behind enemy lines, irregular operations, activities that don’t match standard military records. It’s possible, even likely, that during the Civil War, Daniel had continued doing what he’d always done, moving invisibly through the South, targeting those who’d benefited most from slavery, using the chaos of war as cover.

And if he’d been operating unofficially, perhaps with tacit approval from Union intelligence officers who appreciated the tactical value of his work, but couldn’t officially sanction it, there would be no records. Another fragment appears in a collection of letters housed at the Smithsonian. In 1870, a Freedman’s Bureau officer named Thomas Whitmore wrote to his superior about his work establishing schools for freed slaves in rural Georgia.

In one letter, Whitmore mentioned encountering a remarkable elderly negro man who was teaching children to read in a small community near Savannah. This man, Whitmore wrote, possesses an extraordinary level of education for someone born into slavery. He reads Latin and Greek. He understands mathematics and natural philosophy. He speaks multiple languages, including what he tells me are several African dialects.

When I asked him where he received such education, he smiled and said he’d been teaching himself for 40 years by any means necessary. He carries himself with a dignity that I’ve rarely seen in men of any race. The children are slightly afraid of him, though he treats them kindly. One child told me they call him Moses because he’s old like the biblical Moses.

The man seems to appreciate the name. Whitmore tried to learn more about this teacher, hoping to recruit him for the Freriedman’s Bureau Educational Program. But when Witmore returned to the community 3 months later, the man was gone. The locals said he’d moved on, heading south toward Florida. They wouldn’t say more. The most detailed account, and the most uncertain, comes from an oral history recorded in 1935 as part of the Federal Writers Project.

A woman named Rachel Johnson, aged 94, was interviewed in Charleston, South Carolina, about her memories of slavery and reconstruction. Near the end of the interview, she told a story about a man she’d known briefly in 1872. Rachel had been working as aress in Charleston, washing clothes for white families to survive.

One day, an elderly black man came to her door asking for work. He was willing to do odd jobs, repairs, anything that would earn a small wage. Rachel hired him to fix her roof, which had been leaking. The man worked for 3 days, barely speaking, sleeping in a shed behind her house. On the third evening, after completing the work, he sat with Rachel on her porch.

They talked for hours. He told her stories about his life, though he never gave his name. He’d been enslaved on multiple plantations across the South. He’d survived horrors that Rachel, who’d herself endured slavery, found almost unbelievable. He’d witnessed the worst cruelty that human beings could inflict on each other.

And then he told her something that made her blood run cold. He said he’d made a promise to himself as a young man. A promise that for every scar on his back, for every friend sold away, for every child torn from their mother’s arms, for every woman raped, for every man worked to death in the fields, he would exact a price.

He would make the guilty pay. Not all of them, because there were too many, but enough. Enough to send a message. Enough to prove that the supposedly powerless had power after all. How many? Rachel had asked, afraid of the answer. The old man had looked at her with eyes that seemed to contain depths of pain and resolve that no person should have to carry.

I stopped counting after 200,” he’d said quietly. “The number didn’t matter anymore. The principal did.” Rachel asked if he felt any guilt, any remorse for the lives he’d taken. The old man had considered the question seriously before answering. “I feel grief,” he’d said. Grief for what I was forced to become.

Grief for a life spent in violence when I would have preferred peace. But guilt, no. Because every man I killed had blood on his hands. Everyone had participated enthusiastically in a system built on torture and murder. Everyone had choices and chose cruelty. I simply ensured they faced consequences for those choices. In a just world, they would have faced legal consequences.

But we didn’t live in a just world. So I became the consequence they couldn’t avoid. He’d left the next morning. Rachel never saw him again. She told the interviewer in 1935 that she’d thought about that conversation for over 60 years, wondering if the old man had been telling the truth or simply telling stories.

But she believed he’d been truthful because of the weight in his voice, the sorrow in his eyes, the sense that he was carrying a burden no one else could understand. “If he was who I think he was,” Rachel said at age 94, “Then I hope he found some peace before he died, because a man who carries that much violence, even righteous violence, that man’s soul must be heavy beyond measure.” The interview ends there.

Rachel died 3 months later. The old man she described was never identified. No death record exists for anyone matching his description in Charleston in the 1,870 seconds or 1,880 seconds. And that’s where the trail ends. No definitive proof of what happened to the man who killed at least 200, possibly 250 or more white men over three decades without being caught.

No grave marker, no death certificate, no final accounting. What we’re left with is a mystery wrapped in legend, wrapped in the deliberate historical amnesia that America has imposed on the darkest chapters of its past. The story of Daniel or Moses or whatever his real name was challenges the comfortable narrative we’ve constructed about slavery and resistance.

We want our history to be simple. We want enslaved people to be sympathetic victims who suffered nobly until white abolitionists freed them. We want the violence of slavery to flow in only one direction. We want to believe that the system ended through political processes and military campaigns, not through the accumulated actions of thousands of individuals who resisted in whatever ways they could.

But the truth is always more complex. The truth is that some enslaved people didn’t wait for salvation. Some fought back with every weapon available to them, including violence. Some became what their oppressors forced them to become, killers, and some were extraordinarily effective at it. The documented evidence is undeniable.

Between 1,832 and 1,865, over 200 white men involved in the slave system died under suspicious circumstances across the American South. Many of these deaths showed common characteristics. They occurred near plantations, involved victims who’d been particularly cruel, happened during times when a specific individual was present or nearby, and were ruled accidents or natural causes despite inconsistencies in evidence.

Investigators at the time recognized a pattern. They hired detectives. They offered rewards. They organized manhunts. They tortured suspected collaborators. and they failed completely to capture whoever was responsible. The enslaved communities of the South maintained absolute silence about these deaths, a conspiracy that involved thousands of people across decades.

That silence speaks to how these communities viewed the killings, not as crimes, but as justice, not as terrorism, but as warfare, not as murder, but as execution. And perhaps most importantly, the story reveals something that makes many people uncomfortable. The enslaved population wasn’t helpless. They had agency. They had the ability to resist, to organize, to fight back.

The fact that one person or even several people could wage a 30-year campaign of targeted killings proves that the slave system, despite its overwhelming violence, had vulnerabilities. This matters because it changes how we understand that period of history. It transforms enslaved people from passive victims into active agents of their own liberation.

It acknowledges that the end of slavery came not just from political debates and military campaigns, but from the accumulated resistance of people who refused to accept their bondage. Was Daniel real? Did one man really kill 250 people and evade capture for three decades? or was he a composite, a legend created from the actions of many resistors whose individual stories were forgotten? Honestly, it doesn’t matter whether Daniel was one person or many, whether the death toll was 250 or 150 or 300, whether specific incidents happened

exactly as described, the fundamental truth remains. Enslaved people resisted. Some of that resistance was violent. Some of it was effective. And the people who benefited from slavery lived in fear because of it. That fear was justified, that resistance was real, and that history deserves to be told, even when it’s uncomfortable, even when it challenges our preferred narratives.

Even when it forces us to acknowledge that oppressed people sometimes become what they must to survive and to fight back. The story of Moses, the angel of death who moved through the antibbellum south, leaving dead slaveholders in his wake, is part of American history, whether we want to acknowledge it or not. It’s buried in archives.

It’s preserved in oral traditions. It’s documented in fragmentaryary records that historians have largely chosen to ignore because it doesn’t fit the comfortable story we want to tell about ourselves. But ignoring uncomfortable history doesn’t make it less true. It just makes us less informed, less honest, less willing to confront the full complexity of who we are and where we came from. So, let me ask you this.

Do you believe one man could have done this? Could someone with the right combination of intelligence, patience, skill, and absolute commitment wage a 30-year war against a system that enslaved millions? Could the enslaved communities of the South really maintain that level of secrecy across decades? Could someone kill 250 people and never be caught despite massive investigations? Or is this a myth? A story created to give hope to the hopeless? A legend that communities told themselves because they needed to

believe resistance was possible. What do you think happened to Daniel after the Civil War? Did he die quietly in some freedman settlement, his identity never revealed? Did he continue his work during reconstruction, targeting the former slaveholders who tried to reimpose their control? Or did he escape to some other life, perhaps teaching children to read, perhaps finally finding peace after decades of violence? Tell me in the comments what you believe.

And if you think this story deserves to be heard, that this hidden history needs to be brought into the light, then share this video. Because there are dozens, maybe hundreds of stories like this buried in archives and preserved in oral traditions. Stories of resistance that don’t make it into textbooks. Stories that challenge our comfortable narratives.

stories that reveal the full complex, violent, inspiring truth of how America really became America. Subscribe to The Sealed Room for more stories from the shadows of history. Hit that notification bell because next week I’m bringing you another mystery that historians tried to bury. Another story that will change how you see America’s past.

And remember, history is never as simple as they teach you in school. The truth is always more complex, more disturbing, and more powerful than the sanitized version. Sometimes the heroes were violent. Sometimes the victims fought back. Sometimes justice came from unexpected places. And sometimes the monsters we learn to fear were created by the even greater monsters who built systems of oppression so brutal they produced their own destroyers.

That’s the real story of the slave who eliminated 250 white men and was never seen again. Not a story of a monster, but a story of what oppression creates when it pushes people beyond breaking. A story of resistance in its roarest, most uncompromising form. A story that America would rather forget, but which refuses to stay buried. See you in the next