On the night of December 18th, 1859 at Belmont Plantation in St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, the 17th Overseer died screaming in his cabin. The copperhead viper that killed him disappeared into the Louisiana swampland before anyone could catch it.

Doctors called it a tragic accident. Another unfortunate encounter with the deadly serpents that inhabited the sugar country. They had no idea they were witnessing the final act of the most methodical, scientifically sophisticated resistance campaign in American slavery history. The woman responsible had been planning these deaths for 9 months, ever since three overseers whipped her 11-year-old son to death in a cane field and left his small body there as a warning to others.

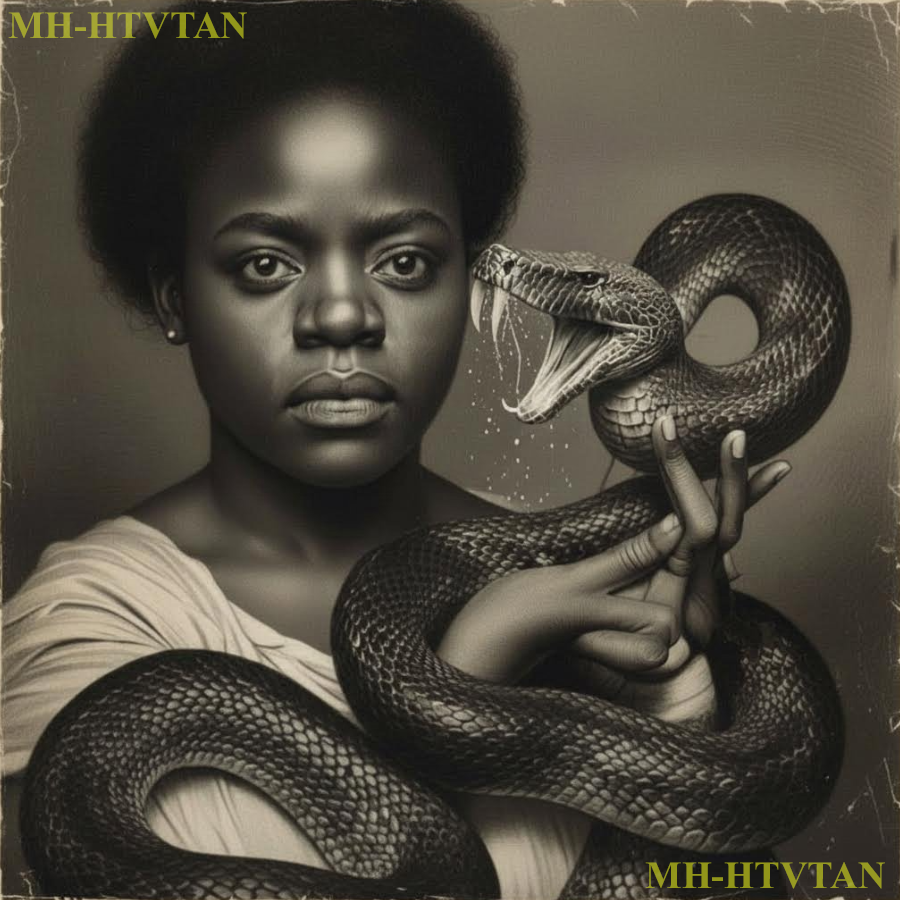

Her name was Manurva Hall, and she possessed knowledge that would transform Louisiana’s most feared reptiles into instruments of justice. Belmont plantation sprawled across 3,000 acres of fertile Louisiana soil in St. Mary Parish, where the Achafallayia River fed the richest sugarcane fields in the South.

The land had made the Bowmont family one of the wealthiest in Louisiana. They owned 437 enslaved people who worked the cane from sun up to sun down. their labor transforming raw sugarcane into white gold that filled the Bowmont coffers with money beyond measure. The big house stood like a white monument to that wealth, its Greek revival columns rising three stories high, its galleries wrapped in ornate iron work imported from New Orleans.

Inside, crystal chandeliers from France caught the light. Mahogany furniture from Cuba filled the rooms and Persian rugs from the oriented floors of imported Italian marble. This was wealth built entirely on the backs of people treated as property, their suffering invisible behind the plantation’s cultivated beauty.

Master Phipe Bowmont ruled this empire with absolute authority. At 53 years old, he had inherited the plantation from his father and expanded it into one of Louisiana’s most profitable operations. He prided himself on running what he called a modern, efficient enterprise, which meant extracting maximum labor from enslaved people through a system of overseers who used fear and punishment to maintain productivity.

17 overseers worked under Bowmont’s direction, each responsible for a specific section of the plantation. They were white men, mostly poor and landless, who found power in their positions and wielded it brutally. The whip was their primary tool of management, and they used it freely. Bowmont rarely involved himself in the day-to-day violence, preferring to let his overseers handle what he called labor discipline, while he focused on profit margins and expansion plans.

This distance allowed him to maintain the fiction that he was a benevolent master even as the people he enslaved suffered under a regime of systematic cruelty. Among the 437 enslaved people at Belmont, Manurva Hall occupied a unique position. At 34 years old, she was the plantation’s reptile specialist, a role that existed nowhere else in Louisiana sugar country.

Her official responsibility was pest control, keeping the venomous snakes that inhabited the swamplands and cane fields away from areas where they might threaten the Bowmont family or interfere with plantation operations. It was dangerous specialized work that required knowledge most people didn’t possess and courage most people didn’t have.

Manurva had both. She could identify 23 species of Louisiana snakes by sight, distinguish venomous from harmless varieties at a glance, predict serpent behavior based on season and temperature, and handle even the deadliest vipers with calm confidence that bordered on supernatural. The enslaved community whispered that she could speak to snakes, that she had inherited powers from African ancestors who commanded serpents.

The truth was simultaneously more mundane and more remarkable. Manurva had learned herptologology from Dr. Jean Baptiste, a French naturalist who visited Belmont Plantation in 1837 when Manurva was 12 years old. Llur had come to Louisiana to study the region’s unique reptile populations, and he needed someone to help him navigate the swamps and locate specimens.

Master Bowmont, seeing an opportunity to appear cultured and scientific to his peers, had volunteered Manurva, who even at 12, showed no fear of the snakes that terrified others. What began as simple assistance evolved into genuine education. Unlike most white men in Louisiana, believed intelligence had nothing to do with skin color, and he recognized inyoung Manurva an exceptional mind.

Over four years of seasonal visits, he taught her everything he knew about reptiles. He showed her how to identify species by scale patterns and head shapes. He explained venom composition and delivery mechanisms. He taught her breeding behaviors and habitat preferences. He trained her in safe handling techniques and first aid for bites.

Most importantly, he taught her to observe and think scientifically, to see patterns and make deductions. based on evidence rather than superstition. By the time L clerk stopped visiting in 1841, he died of yellow fever in New Orleans. Manurva possessed knowledge that would have earned her a university position if she had been born white and male.

Instead, she was enslaved property whose expertise made her valuable to the Bowmont family, but whose intelligence remained invisible to them. They saw her skill with snakes as a curious talent like a dog that could perform tricks, never recognizing the scientific sophistication behind it. This blindness would prove fatal for 17 men.

Manurva’s daily routine began before dawn. She would walk the plantation’s perimeter, checking areas where venomous snakes commonly appeared. Copperheads favored the wood piles near the slave quarters. Cotton mouths congregated along the irrigation ditches that crisscrossed the cane fields. Coral snakes, rare but deadly, occasionally appeared in the gardens near the big house.

When she found a serpent in a dangerous location, Manurva would capture it using a specially designed hooked stick and a canvas bag, then release it deep in the swamp where it posed no threat to humans. She maintained detailed mental records of snake populations, seasonal patterns and behavioral changes. She could predict with remarkable accuracy when and where dangerous encounters were likely to occur, and she took pride in preventing them.

For 18 years, not a single person at Belmont Plantation died from snake bite. This perfect safety record would make the deaths that began in April 1859 all the more shocking. The enslaved community at Belmont respected Manurva’s knowledge and trusted her skill. Children were taught to find her immediately if they saw a snake.

Adults called her to inspect suspicious rustling in the cane or investigate strange marks that might indicate serpent presence. She had saved dozens of lives over the years, extracting venom from bite victims with techniques had taught her, applying pressure bandages, administering herbal remedies that slowed venom spread.

She was healer and protector, using her unique knowledge to shield her community from one of the swamps many dangers. The overseers viewed her differently. To them she was the snake woman useful for keeping reptiles away from the big house but otherwise beneath notice. They never spoke to her directly unless giving orders.

They certainly never imagined that the quiet woman who handled serpents with such calm competence was also studying them, learning their patterns, noting which overseers walked alone through the cane fields at night, observing who drank heavily and stumbled on the way back to their cabins. cataloging vulnerabilities with the same scientific precision she applied to snake behavior.

Behind the slave quarters, hidden in a dense thicket of palmetto and live oak, Manurva maintained what she called her sanctuary. It appeared to be simply a place where she released captured snakes before transporting them to the deep swamp, a temporary holding area that kept serpents contained until she could make the longer journey to safe release sites.

In reality, it was something far more sophisticated. Over the years, Manurva had constructed a vivarium, a carefully designed habitat where she could observe snake behavior in controlled conditions. She had built it slowly using scrap wood from plantation repairs, clay from the riverbank, stones from the fields. The structure was camouflaged so thoroughly that someone could walk within 5 ft and never notice it.

Inside, she maintained separate compartments for different species. Each environment tailored to specific needs. Temperature, humidity, hiding places, water sources, everything was optimized to keep serpents healthy and calm. This was where Manurva conducted her real education. The observations that went far beyond what had taught her.

She studied how snakes responded to different scents, what attracted or repelled them. She experimented with feeding schedules and learned to associate food with specific signals. She discovered that copperheads, contrary to popular belief, could learn to recognize individual humans by scent and would respond differently to different people.

This knowledge accumulated over nearly two decades of patient observation would become the foundation of her vengeance. Manurva lived in cabin 17 of the slave quarters, a rough structure she shared with her son, Marcus, and two other women whose husbands had been sold awayyears earlier.

The cabin measured 16 ft by 14 ft with a dirt floor, a single window with no glass, and a fireplace that provided their only heat and cooking fire. Four adults and one child lived in a space smaller than the Bowmont family’s dining room. At night they slept on pallets stuffed with corn husks, their bodies crowded together for warmth in winter.

The cabin leaked when it rained. Gaps in the walls let in wind and insects. It was a dwelling that would have been considered inadequate for livestock. Yet it housed human beings whose labor generated thousands of dollars in annual profit for the Bowmont family. This was the reality behind the plantation’s beautiful facade.

The invisible suffering that made white wealth possible. Marcus Hall was 11 years old in March 1859. A bright, curious child who had inherited his mother’s intelligence and her fearlessness. He helped Manurva with her snake work sometimes, learning to identify species and understanding the basics of safe handling. She had taught him to read using a Bible she had hidden for years, a dangerous act that could have resulted in severe punishment if discovered.

Marcus could recite passages from memory, and had begun teaching other enslaved children their letters, using sticks to scratch words in the dirt. He dreamed of freedom, asked his mother constant questions about the north, wondered aloud if they might someday escape to the places where black people could live free.

Manurva always answered carefully, never quite encouraging, but never quite discouraging either. She wanted him to have hope, but she also understood the brutal reality of their situation. Escape from a Louisiana sugar plantation was nearly impossible. The swamps were vast and deadly. The patrols were efficient and violent.

The penalties for attempted flight were horrific. She told Marcus they would be free someday somehow, and she let him believe it might happen in his lifetime. She never imagined that belief would get him killed. In early March 1859, a barrel of raw sugar went missing from the plantation’s processing house. It was a relatively small theft, perhaps 20 of the brown unrefined sugar that enslaved people sometimes stole to supplement their meager rations.

Master Bowmont demanded the overseers find the thief and make an example of them. Three overseers, Samuel Garrett, William Hughes, and Thomas Morrison, decided Marcus was responsible based on no evidence whatsoever. They had seen him near the processing house 2 days earlier. This was enough for them. They didn’t investigate, didn’t question, didn’t consider that dozens of people passed the processing house daily.

They simply grabbed Marcus from the cane field where he was working on March 14th, 1859, and dragged him to the whipping post in full view of the other enslaved workers. The events that followed would be seared into Manurva’s memory with absolute clarity. Every detail preserved in perfect agonizing detail.

She heard Marcus screaming for her and ran from the swamp where she had been collecting a cotton mouth. By the time she reached the whipping area, they had already stripped off his shirt and tied his wrists to the post. Garrett held the whip, a braided leather weapon designed to tear flesh. Manurva tried to intervene, tried to explain that Marcus would never steal, that he was a good child, that there was no evidence.

Morrison struck her across the face and told her to shut her mouth or she would be next. They made her watch. They wanted her to watch. This was part of the punishment, part of the lesson they were teaching. Garrett brought the whip down across Marcus’s back. The child screamed. Manurva tried to close her eyes and Morrison forced them open, his hand gripping her face, his breath hot and tobacco stained.

“You watch,” he hissed. “You watch what happens to thieves.” 50 lashes was the sentence Garrett announced. By the 20th, Marcus had stopped screaming. By the 30th, he had stopped moving. By the 40th, Manurva knew he was dying. She could see it in the way his body hung limp, in the blood pooling at the base of the post, in the terrible silence where his voice had been. They didn’t stop at 40.

They continued to 50, whipping a child who was already dead. Their brutality so complete it required no living victim. When they finally cut him down, his back was destroyed. The skin flayed away to reveal muscle and bone. They dumped his small body in the cane field and left it there for the rest of the day.

Let everyone see, Hughes said. Let everyone remember what happens to thieves. They wouldn’t let Manurva touch him until sundown. For 7 hours, she sat 15 ft from her son’s body, forced to look at what they had done, forced to smell his blood in the Louisiana heat, forced to listen to the flies that gathered.

Other enslaved people brought her water. They tried to offer comfort. There was no comfort possible. At sundown, they finally allowed her to collect Marcus’sbody. She carried him to the slave cemetery, a plot of weedy ground behind the quarters where enslaved people were buried without markers or ceremony. She dug his grave herself, her hands moving mechanically through the dark soil.

She wrapped him in the only cloth she owned, a faded cotton dress that had been her mother’s. She placed him in the ground and covered him. She didn’t cry. She didn’t pray. She simply stood there in the darkness and felt something inside herself die along with her child. The woman who had spent 18 years protecting life, who had saved dozens of people from venomous snakes who had used her knowledge only to heal and preserve, ended that night.

In her place was someone new, someone whose knowledge of serpents would serve a different purpose. The transformation didn’t happen all at once. For the first week after Marcus’s murder, Manurva moved through her days in a state of numb shock. She performed her duties mechanically, capturing snakes and releasing them, checking the grounds, maintaining her appearance of normaly.

But at night, in the darkness of her cabin, the rage would surface. It wasn’t hot rage, the kind that explodes in immediate violence. It was cold and calculating, a fury that crystallized into absolute certainty. The three men who had killed her son would die. the 14 other overseers who had stood by and watched, who had laughed while a child was murdered, who had gone back to their cabins that evening and eaten their dinners while Marcus’s body rotted in the cane field. They would die, too.

All 17. She would make it happen. She would use the knowledge that Dr.Lair had given her, the serpents she had protected and studied, the scientific understanding she had spent two decades accumulating. She would transform her expertise from shield to sword, her life’s work from preservation to destruction. The decision brought a terrible calm, a sense of purpose that cut through the grief like a blade.

The practical planning began in her sanctuary, the hidden vavarium behind the quarters. Manurva had always kept detailed mental records of her observations, but now she began to organize that knowledge with specific intent. She needed to understand not just snake behavior in general, but how to weaponize it. Copperheads would be her primary tool.

Louisiana copperheads were pit vipers equipped with hemotoxic venom that destroyed blood cells and tissue. A bite was rarely fatal to a healthy adult if treated properly. But without treatment or if the victim was weakened by alcohol or illness, death was entirely possible. More importantly, copperhead bites were common enough in Louisiana sugar country that one more would never raise suspicion.

If an overseer died from snake bite, it would be seen as a tragic accident, not murder. This was essential. Manurva needed each death to appear natural, separate from the others, unconnected to any pattern that might suggest deliberate action. Dr. had taught her the basics of venom composition and delivery. But he had never taught her how to direct a snake to bite a specific target.

That knowledge Manurva had to develop herself through patient experimentation. She began with scent. She knew that snakes hunted primarily through chemical detection, using their fork tongues to gather scent particles from the air and analyze them through specialized organs. What she needed to discover was whether she could create a scent that would trigger aggressive response, making a normally defensive snake into an attacking one.

She started with the copperheads in her vivarium, observing their reactions to different substances. She tried sweat- soaked cloth, blood stained fabric, various plant extracts. The breakthrough came when she experimented with urine. Snakes responded aggressively to the scent of predator urine, perceiving it as a threat.

She discovered that if she applied fresh human urine to a cloth and placed it near a copperhead, the snake would strike at the cloth defensively. This was the foundation of her method. Over the next several weeks, Manurva refined the technique. She learned that the response was stronger if the urine came from a person the snake had encountered before.

She discovered that mixing the urine with certain plant compounds intensified the effect. She found that she could condition snakes to associate specific scent combinations with feeding times, creating a Pavlovian response where the scent triggered not just defensive aggression, but hunting behavior.

Most crucially, she learned that she could apply these scent compounds to clothing in ways that were invisible and odless to humans, but overwhelming to serpentine senses. A person wearing clothing treated with her specially prepared compound would become an irresistible target for a properly conditioned copperhead. The snake would seek them out, strike them, and then disappear, leaving behind what appeared to be an unfortunate encounter with Louisiana’s venomous wildlife. Thepractical challenges were significant.

She needed to obtain samples from her targets without their knowledge. She needed to train individual snakes to respond to specific scent profiles. She needed to track the overseers movements and identify opportunities when they would be alone and vulnerable. She needed to position her weapon serpents in locations where they would encounter their targets but could escape afterward.

Each kill would require weeks of preparation, careful observation, and precise execution. Manurva approached it with scientific method, the same patient, systematic approach she had used in her legitimate research. She created mental files on each of the 17 overseers, noting their habits and patterns. Samuel Garrett drank heavily and stumbled back to his cabin alone each night around 10:00.

William Hughes made rounds of the cane fields just after dawn, walking the same path every morning. Thomas Morrison visited the processing house twice daily, always at the same times. Each man had routines, vulnerabilities, moments when they were alone and would be for several minutes. These were the windows Manurva would exploit.

Obtaining scent samples proved simpler than she had expected. As the plantation’s reptile specialist, she had access to areas most enslaved people couldn’t enter. She could walk past the overseer’s cabins, checking for snakes. She could enter the processing house, the equipment sheds, the storage buildings. In each location, she would find clothing the overseers had discarded, chamber pots they had used, personal items bearing their scent.

She would collect tiny samples, a few drops of urine soaked into a cloth, a scrap of sweat stained shirt, a rag used for washing. Back in her sanctuary, she would use these samples to condition specific snakes, training them to associate each overseer’s unique scent profile with feeding time, creating an aggressive hunting response.

It was patient, methodical work that took months to complete properly. Manurva had time. She had patience. She had absolute focus born from grief transformed into purpose. By early April 1859, barely 3 weeks after Marcus’ murder, Manurva had completed her preparations for the first kill.

Her target was Samuel Garrett, the overseer who had wielded the whip that killed her son. She had selected a copperhead she called number three, a mature female with a particularly aggressive temperament. For two weeks, she had conditioned number three to associate Garrett’s scent with food, presenting the scent moments before feeding until the snake’s response was immediate and reliable.

She had tracked Garrett’s evening routine and identified the perfect location, a path through dense palmetto brush that he used as a shortcut back to his cabin after drinking at the overseer’s quarters. The path was isolated, the undergrowth thick enough to hide a snake, the lighting poor. On the night of April 7th, 1859, Manurva treated Garrett’s jacket with her compound while he was drinking.

He had left it hanging on a porch rail, and it took her less than 30 seconds to apply the invisible, odless mixture. Then she positioned number three along the path, placed the scented jacket nearby to anchor the snake’s attention to that location, and retreated to wait. Garrett came stumbling down the path around 10:30, drunk and off balance.

Number three, attracted by the overwhelming scent signature from his treated jacket, emerged from the palmetto and struck him on the left calf. The bite was clean and solid, venom injected deeply into muscle tissue. Garrett barely noticed at first, his alcohol-dulled senses not registering the quick strike, he continued walking, and number three disappeared back into the undergrowth.

Heading toward the swamp, as Manurva had trained her to do after feeding, by the time Garrett reached his cabin, the venom was already at work. Heotoxins began destroying blood cells, breaking down capillary walls, causing internal bleeding. Garrett became confused, nauseiated, then violently ill. He tried to call for help, but was too disoriented to make himself understood.

By dawn on April 8th, he was dead. The official cause recorded in the plantation’s ledger was snake bite accidental. A tragedy, everyone agreed, but not unexpected in Louisiana swamp country. No one suspected murder. No one even considered the possibility. Manurva attended his burial with the other enslaved people, her face carefully neutral, her expression revealing nothing.

Inside she felt the terrible satisfaction of justice beginning to be served. One down, 16 to go. The second death came 3 weeks later on April 28th. William Hughes died from a copperhead bite sustained during his morning rounds of the cane fields. The snake number seven in Manurva’s mental catalog had been positioned along Hughes’s usual path and conditioned to his scent profile for nearly a month.

The bite occurred at approximately 6:15 in the morning. Hughes died by noon. Again, thedeath was recorded as accidental. Again, no suspicion arose. Manurva had learned from the first kill. She varied the timing, changed the location, used a different snake with a different temperament. She was careful to maintain her normal routine, careful to show no unusual interest in Hughes’s death, careful to remain the quiet, competent snake woman who simply did her job.

The other enslaved people noticed nothing unusual. The overseers noticed nothing at all. Thomas Morrison died on May 19th. Michael O’ Conor died on June 3rd. Patrick Sullivan died on June 24th. Each death appeared isolated, accidental, unconnected to the others, except by the unfortunate commonality of snake bite in a region where venomous serpents were abundant. Manurva varied everything.

time of day, location, method of scent application, type of snake used. She never repeated a pattern. She never killed two overseers in the same week. She carefully maintained intervals that seemed random, but were actually calculated to avoid any appearance of pattern. She was executing a campaign of serial murder with scientific precision, and no one suspected because everyone believed they understood what was happening.

Snakes bit people in Louisiana. Sometimes people died. It was unfortunate but natural. The possibility that someone was orchestrating these deaths, training serpents to kill specific targets, seemed so absurd that no one even considered it. By late summer 1859, six overseers were dead. The remaining 11 were becoming nervous.

They talked among themselves about the unusual number of snake bites. wondered if something in the environment had made the serpents more aggressive. Some suggested they should clear more of the undergrowth around the plantation. Others proposed organizing hunts to reduce the snake population. None of them suggested the truth that a 34year-old enslaved woman was systematically murdering them using knowledge that would have been impossible for most scientists of the era to achieve.

Their blindness to the possibility was rooted in their fundamental assumptions about enslaved people. They couldn’t imagine that someone they considered property could possess such sophisticated understanding, could execute such a complex plan, could transform scientific knowledge into a weapon. Their racism made them vulnerable.

Their certainty of black intellectual inferiority creating a blind spot that Manurva exploited ruthlessly. The psychological toll of the campaign was significant. Manurva was maintaining an elaborate double life, appearing normal and competent by day while planning murder by night. She slept little, her mind constantly working through the logistics of the next kill.

She dreamed of Marcus, saw his small body in the canefield, woke, gasping with rage and grief. The only thing that kept her functional was the sense of purpose, the steady progress toward justice. Each death brought a grim satisfaction, a feeling that the cosmic balance was being restored one body at a time. She kept a mental count.

17 overseers had watched her son die. She would take 17 lives in return. Perfect symmetry, perfect justice. The seventh death occurred on August 9th. James Wellington died from a copperhead bite while checking irrigation ditches. The eighth came on August 30th. Charles Brennan bitten while walking between the processing house and the equipment shed.

The 9th was September 18th. Robert McKenzie struck while inspecting stored equipment. The 10th came on October 5th. David Foster bitten during an evening walk. Each death followed the same pattern. Isolated victim, lone snake, quick strike, rapid departure of the serpent, death within hours. Each time, plantation doctors declared it an unfortunate accident.

Each time the body was buried, and life continued. The enslaved community began to whisper about divine judgment, about God’s wrath falling on those who had killed a child. Some believed the snakes themselves were instruments of heavenly vengeance guided by supernatural forces to strike down the guilty.

Only Manurva knew the truth was both more mundane and more remarkable. This was human justice achieved through human intelligence and scientific knowledge. There was nothing supernatural about it except the precision with which she was executing her plan. By November 1859, 14 overseers were dead. The three remaining were the same three who had directly killed Marcus.

Morrison had already fallen on May 19th, but Hughes and a final overseer named Christopher Blake was still alive. The plantation was in chaos. Master Bowmont had brought in new overseers to replace the dead, but they were nervous and ineffective, constantly looking over their shoulders, afraid to walk alone.

Productivity dropped as the atmosphere of fear spread. Bumont himself was baffled by the deaths, unable to explain why so many men were dying from snake bites when the plantation had gone 18 years without a single fatality.He brought in snake hunters from New Orleans, men who cleared acres of undergrowth and killed hundreds of serpents. It made no difference.

The deaths continued because Manurva’s weapon serpents were carefully protected in her hidden vavarium, brought out only for specific missions, then returned to safety. The hunters were killing the wrong snakes, random wild serpents that had nothing to do with the orchestrated murders.

The 11th through 16th deaths occurred in quick succession in late November. November 7th, 9th, 12th, 15th, 19th, and 23rd. Manurva accelerated the pace deliberately, knowing that her escape window was closing, that the sheer number of deaths would eventually trigger real investigation. She needed to complete her mission before that happened.

Each kill was executed with the same meticulous care as the first, but the intervals between them shortened. The remaining overseers were terrified, refusing to walk anywhere alone, huddling together in groups, sleeping with lamps lit. It didn’t save them. Manurva found opportunities, created vulnerabilities, struck with serpentine patience and precision.

The 17th and final death was Christopher Blake on December 18th, 1859. Blake had been one of the three who killed Marcus, and Manurva saved him for last deliberately. She wanted him to know fear, wanted him to watch 16 men die and understand his turn was coming. On the evening of December 18th, she positioned number three, the same copperhead that had killed Samuel Garrett 9 months earlier in Blake’s cabin.

She had treated his bedding with her compound, creating an irresistible scent lure. When Blake entered his cabin that evening, number three was waiting beneath his blanket. The strike came the moment Blake’s hand touched the bed. The venom entered through his palm, the most effective location for rapid distribution through the bloodstream.

Blake screamed. He tried to get help. He died within 3 hours. His last moments filled with the terror and pain he had inflicted on an 11-year-old child. Manurva was in her cabin when it happened, sitting calmly, counting the minutes until justice was complete. 17 dead. The balance restored. The morning after Blake’s death, Manurva began preparations for her escape.

She had always known this moment would come, had been planning it alongside the murders. The plantation was in total chaos, overseers terrified, enslaved people whispering about divine judgment. Master Bowmont, desperate for answers. In the confusion, Manurva quietly gathered what little she owned, left her cabin before dawn, and walked into the swamp.

She had studied these waterways for years, knew every path and channel. She traveled north, following routes she had memorized long ago, moving with purpose through terrain that would have killed most fugitives. She had food hidden along the way, supplies cashed years earlier. She had maps memorized from conversations with other escapees, names of safe houses, passwords for the Underground Railroad.

Her knowledge of the natural world, the same expertise she had used to kill 17 men now served to keep her alive through the dangerous journey north. The discovery of her vivarium came 3 days after her escape. One of the new overseers, searching desperately for the source of the deadly snakes, stumbled across the carefully camouflaged structure behind the quarters.

Inside he found the empty compartments where Manurva had kept her weapon serpents, the feeding logs she had maintained in careful pictographs, the scent compounds she had developed. Most chillingly, he found a piece of cloth with 17 marks on it, one for each dead overseer and a note written in careful English. 17 serpents, 17 lives.

Nature restored the balance. The revelation that the snake bite deaths had been deliberate murder sent shock waves through Louisiana. The authorities launched a massive manhunt, but Manurva had a three-day head start and knowledge of terrain they couldn’t match. She had disappeared into the swamps like one of her own serpents, silent and impossible to track.

Manurva Hall reached Canada in March 1860, exactly 1 year after her son’s murder. She settled in a small community of formerly enslaved people near Toronto, took the surname Freeman, and lived quietly for the next 31 years. She never spoke publicly about what she had done in Louisiana, never confessed to the murders, never expressed regret.

Those who knew her in Canada described her as a gentle woman who kept a small garden and loved to observe the local wildlife. She died peacefully in her sleep on April 3rd, 1891 at the age of 66. She was buried in a cemetery for free black people. Her grave marked with a simple stone bearing the name Manurva Freeman.

[clears throat] Back in Louisiana, the legend of the viper breeder grew over the years. Some white historians portrayed her as a monster, a murderous savage who killed 17 innocent men. But in the enslaved community and among their descendants,Manurva Hall became something else entirely. A hero who used her intelligence and knowledge to achieve justice when the law offered none.

Stories about her were passed down through generations. Details embellished and mythologized. Some said she could transform into a snake herself. Others claimed she commanded an army of serpents that did her bidding. The truth that she was a self-taught scientist who weaponized her expertise against her oppressors was somehow both more remarkable and more threatening than the myths.

It suggested that enslaved people possessed intelligence, capability, and agency that the system of slavery denied. It proved that knowledge was power even in the most powerless hands. The Belmont plantation never fully recovered from the deaths of 17 overseers in 9 months. Master Phipe Bowmont sold the property in 1861 and it changed hands several times before eventually being abandoned.

The buildings fell into decay. The fields returned to swamp land and by the end of the 19th century, Belmont had vanished completely, reclaimed by the Louisiana wilderness. Local residents said the land was cursed, that the ghosts of the dead overseers haunted the ruins. No one wanted to live where 17 men had died from snake bites that might not have been accidental at all.

The plantation that had once generated massive wealth through enslaved labor ended as a cautionary tale, a reminder that systems of oppression created their own destruction. Modern historians studying the case of Manurva Hall have documented it as one of the most sophisticated resistance actions in American slavery history.

The level of scientific knowledge required to breed, condition, and deploy venomous snakes as targeted weapons was extraordinary for anyone in the 1850s, much less an enslaved woman with no formal education. The fact that she executed 17 murders over nine months without ever being caught in the act demonstrates planning and execution skills that would be remarkable in any context.

Some scholars have compared her methods to modern biological warfare, noting that she essentially created and deployed living weapons with precision that anticipated techniques not formally developed until the 20th century. Her ability to operate undetected for so long reveals both her intelligence and the profound blindness of the system that enslaved her.

A blindness born from the racist assumption that black people were intellectually inferior and incapable of such sophisticated action. The moral questions raised by Manurva Hall’s actions remained complex and unresolved. Was she a murderer who killed 17 men, some of whom had not directly harmed her son? Or was she a resistance fighter who struck back against an oppressive system using the only weapon available to her? The answer depends partly on how one views violence in the context of slavery.

The institution itself was founded on violence. The violence of kidnapping, the violence of forced labor, the violence of family separation, the violence of the whip. Enslaved people existed in a state of constant physical and psychological assault. When Manurva used violence in response, was she initiating aggression or defending herself and her community? The law of the time was clear.

She was property, had no right to defend herself, and killing white men was an unforgivable crime. But moral law and legal law are not always the same. Many modern ethicists argue that enslaved people had the right to resist their enslavement by any means necessary. That the violence of slavery created a moral space where violent resistance was justified self-defense.

The question of collective versus individual guilt also complicates moral assessment. Three overseers directly killed Marcus Hall. Manurva killed those three plus 14 others who had witnessed the murder and done nothing. Were those 14 guilty by their inaction, by their participation in the system of slavery, by their daily violence against enslaved people? There are no easy answers.

What is clear is that Manurva made a calculated decision to punish not just the men who wielded the whip, but the entire system they represented. She understood that the three direct killers were interchangeable parts in a larger machine of oppression, that tomorrow three different overseers might commit the same act, that the problem was structural, not individual.

By killing 17 men, she struck at the structure itself, made the position of overseer at Belmont Plantation so dangerous that no one wanted to take it, effectively shutting down the plantation’s operations. In that sense, her violence had strategic purpose beyond revenge. The role of knowledge and education in Manurva’s story raises profound questions about power and access. Dr.

Jean Batist L Clerk gave her scientific knowledge that the system of slavery specifically denied enslaved people. Reading and education were forbidden because enslavers understood that knowledge was power, that an educatedenslaved person was dangerous to the system. Manurva proved them right. The herptology education cleric provided became a weapon more effective than any gun or knife.

It allowed her to kill 17 men without ever being in the same room with them, without leaving evidence that contemporary science could detect, without raising suspicion until it was too late. Her case demonstrates why enslavers feared educated enslaved people because intelligence and knowledge could transform the powerless into agents of change, could turn the tools of oppression into instruments of liberation.

The story also illuminates the invisible labor and expertise that enslaved people contributed to the southern economy and society. Manurva’s knowledge of Louisiana reptiles was unique and valuable. She prevented snake bites, saved lives, and made the plantation safer for 18 years. This expertise required intelligence, dedication, and skill equivalent to that of university trained naturalists.

Yet, because she was enslaved, her knowledge was treated as a curiosity rather than achievement, her expertise exploited without recognition or reward. When historians calculate the economic value of slavery, they typically count only physical labor, cottonpicked, sugar harvested, crops planted. They rarely account for the intellectual contributions of enslaved people like Manurva, whose specialized knowledge made plantations function more efficiently.

Her story suggests that the true cost of slavery includes not just the physical labor stolen from millions of people, but also the intellectual contributions taken without acknowledgement and the scientific advances that might have occurred if those minds had been free to pursue knowledge for its own sake. The fact that Manurva Hall reached freedom and lived out her life in Canada complicates the narrative of her story.

She wasn’t captured. She didn’t die in a dramatic confrontation. She simply executed her mission, escaped, and lived another 31 years in peace. This ending satisfies a desire for justice that many slavery resistance stories don’t provide. Most enslaved people who resisted violently were caught and killed, their resistance ending in martyrdom.

Manurva achieved her vengeance and escaped consequence, at least legal consequence. Whether she suffered psychological consequence, guilt, trauma, nightmares, we cannot know. The historical record shows only that she lived quietly and peacefully in Canada until her death at 66. Some interpret this as evidence that she felt no remorse, that she believed her actions were fully justified.

Others suggest that her quiet life might have been a way of processing tremendous trauma, that peace was what she sought after years of violence and loss. The truth remains unknowable, buried with her in a Toronto cemetery. The preservation of Manurva Hall’s story through oral tradition in the black community reveals how marginalized groups maintain their own historical narratives outside official channels.

White historians of the 19th and early 20th centuries either ignored her story or presented her as a cautionary tale about savage violence. But in black communities across Louisiana and beyond, her story was told differently as inspiration, as proof of intelligence and capability, as evidence that enslaved people were not passive victims, but active resistors.

This parallel historical narrative existed alongside the official version preserved through family stories, church teachings, and community memory. When professional historians finally began recovering these hidden narratives in the late 20th century, they discovered a much richer and more complex history of slavery than the official record suggested.

Manurva’s story was one of thousands preserved this way, protected by communities that understood the importance of remembering resistance even when the dominant culture wanted to forget. The scientific sophistication of Manurva’s methods has particular relevance for modern understanding of intelligence and capability.

In the 1850s, scientific racism was establishing itself as a supposedly objective field with researchers claiming to prove through skull measurements and anatomical studies that black people were intellectually inferior to whites. Manurva Hall was executing a campaign of biological warfare that required knowledge of reptile behavior, venom composition, scent-based conditioning, and tactical planning that would challenge most modern scientists.

The contradiction is stark. The same society claiming black intellectual inferiority was enslaving people capable of extraordinary scientific achievement. This contradiction reveals scientific racism for what it was, not objective science, but ideology designed to justify oppression. Manurva’s story stands as proof that intelligence and capability have nothing to do with race.

That genius can emerge anywhere, regardless of circumstance, and that systematic denial of education andopportunity is necessary to maintain false hierarchies. The question of whether Manurva’s actions contributed to the abolition of slavery is difficult to answer definitively. Her campaign didn’t spark immediate political change or inspire widespread rebellion.

Belmont Plantation shut down, but other plantations continued operating. The system of slavery endured until the Civil War ended it four years after Manurva’s escape. However, resistance actions like hers, and there were many, though few as sophisticated, contributed to a climate of fear and instability that made slavery increasingly difficult to maintain.

Each act of violent resistance proved that enslaved people were not docile, that the system required constant vigilance and violence to sustain. That the costs of slavery included not just economic investment but physical danger to white people. This accumulation of resistance combined with growing abolitionist pressure in the north and the fundamental economic inefficiency of forced labor created conditions that made slavery vulnerable to political challenge.

Manurva’s 17 deaths were 17 cracks in a system that would eventually shatter for descendants of enslaved people. Manurva Hall’s story carries particular significance. She represents an ancestor who refused to accept dehumanization, who transformed grief into action, who used intelligence and knowledge to strike back against impossible odds.

In the historical narrative that often emphasizes the suffering and victimization of enslaved people, Manurva’s story provides something different. Agency, capability, and power. It says that our ancestors were not just victims but resistors. Not just laborers but thinkers, not just property but human beings who fought for dignity and justice using whatever means available.

This matters for how communities understand their history and themselves. It provides models of strength and resistance that counter narratives of pacivity. It proves that even in the most oppressive circumstances, human agency persists, intelligence survives, and justice can be achieved through determination and skill.

The landscape where Belmont Plantation once stood is now part of Louisiana’s Achafallayia Basin, a vast wilderness of swamps and waterways. No physical trace remains of the buildings, the cane fields, or the lives lived there. Nature has reclaimed it all, as if the earth itself wanted to erase the memory of what happened there.

But in the persistence of swamp and wetland, in the copperheads that still inhabit the undergrowth, there is a fitting memorial to Manurva Hall, she understood these swamps, knew their dangers and their gifts, learned to survive in them, and use them as weapons. The land that was once forced to produce sugar now produces only wilderness, its exploitation ended, its freedom restored.

There is poetry in that transformation, a kind of justice that transcends individual lives and speaks to larger truths about what endures and what fades. On the night of December 18th, 1859, when Christopher Blake died screaming in his cabin, Manurva Hall completed a mission that had consumed nine months of her life.

17 men who had participated in or witnessed her son’s murder, were dead. The mathematical precision of her vengeance, 17 serpents for 17 overseers, reflected her scientific mind, her need for symmetry and completeness. She had transformed knowledge given to her by a French naturalist into a weapon of resistance. She had proven that intelligence and determination could overcome the massive power imbalance of slavery.

She had achieved justice when the legal system offered none, used science when the system denied her education, and survived when survival should have been impossible. Her story remains a testament to human resilience, to the power of knowledge, and to the certainty that oppression will always generate resistance from those who refuse to accept their dehumanization.

The legacy of Manurva Hall extends beyond her specific actions to larger questions about resistance, justice, and memory. How do we judge actions taken in context of extreme oppression? What responsibility do witnesses bear for violence they observe but don’t prevent? When is violent resistance against systemic violence morally justified? These questions have no simple answers, but Manurva’s story forces us to grapple with them honestly.

She lived in a system that denied her humanity, that murdered her child with impunity, that offered her no recourse to justice through law or society. In that context, she made a choice to use the only power available to her, her knowledge of serpents, to achieve justice through her own action.

Whether we judge that choice as righteous vengeance or excessive violence says as much about our own values and circumstances as it does about her actions. What remains undeniable is that she acted with intelligence, courage, and absolute determination. She refused to be a passive victim. Sheinsisted on her humanity through the very act of resistance.

And in doing so, she joined the ranks of countless enslaved people who fought back against their oppression, whose resistance, violent and nonviolent, successful and failed, remembered and forgotten, ultimately contributed to slavery’s destruction. Today, historians recognize Manurva Hall as one of the most remarkable figures in the history of American slavery resistance.

Her story challenges assumptions about who could possess scientific knowledge in the antibbellum south, demonstrates the sophistication of enslaved resistance, and proves that intellectual capability has nothing to do with legal or social status. She was a scientist, a strategist, a mother seeking justice for her murdered child, and a woman who refused to accept the role assigned to her by a system of oppression in the swamps of Louisiana with serpents as her weapons and knowledge as her power.

She struck back against impossible odds and achieved a victory that slave codes said was impossible, and racial ideology claimed unthinkable. Her 17 serpents delivered 17 deaths that proved enslaved people were capable of sophisticated long-term resistance, requiring intelligence and skill that the system of slavery existed to deny.

In that proof lies her greatest legacy. Not just the death she caused, but the lie she exposed and the truth she embodied. Manurva Hall was brilliant, capable, and powerful. Slavery tried to make her powerless. She proved it wrong one serpent at a time until justice was served and balance was restored. The copperheads of Louisiana still inhabit the swamps where she walked.

They still carry venom that can kill. And in their persistence, they remain a reminder of what she was and what she did. A woman who transformed nature into justice and knowledge into freedom.