Beneath the ancient oak trees of St. Michael’s Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina, lie nine graves that the city’s most prominent families refused to discuss. Each headstone bears the name of a wealthy plantation owner who died between 1851 and 1855, all under mysteriously similar circumstances. Sudden paralysis followed by what physicians of the time called merciful death.

But in 1923, when the cemetery underwent renovation, groundskeepers made a horrifying discovery that city officials immediately ordered sealed from public record. Inside each of those nine coffins, the wooden lids bore deep scratch marks from fingernails, and the bodies lay in positions suggesting desperate struggles. What the authorities found next would haunt Charleston’s elite for generations.

A leather journal buried beneath the cemetery’s oldest magnolia tree, written in the careful handwriting of a man named Solomon Fairfax, detailing four years of calculated revenge that began with a family’s screams and ended with nine men buried alive.

The journal’s first entry, dated March 15th, 1851, began with a single line that would explain everything.

Today, I watched my wife and children burn, and I did nothing to stop it. Charleston, in the 1850s stood as the crown jewel of southern aristocracy, where white columned mansions lined the Kooper River, and fortunes built on rice and cotton created dynasties that believed themselves untouchable. The city’s medical community, though small, commanded enormous respect among the wealthy elite, who could afford private physicians for their increasingly frequent ailments, mysterious fevers, sudden weakness, and strange paralytic conditions that seemed to plague

Charleston’s most prominent families with alarming regularity. Dr. Cornelius Hatheraway had established his practice on Meeting Street in 1845, quickly earning a reputation among Charleston’s upper class for his innovative treatments and unusual understanding of exotic remedies. His success stemmed partly from his exceptional assistant, a slave named Solomon Fairfax, who possessed an almost supernatural knowledge of medicinal plants and chemical compounds.

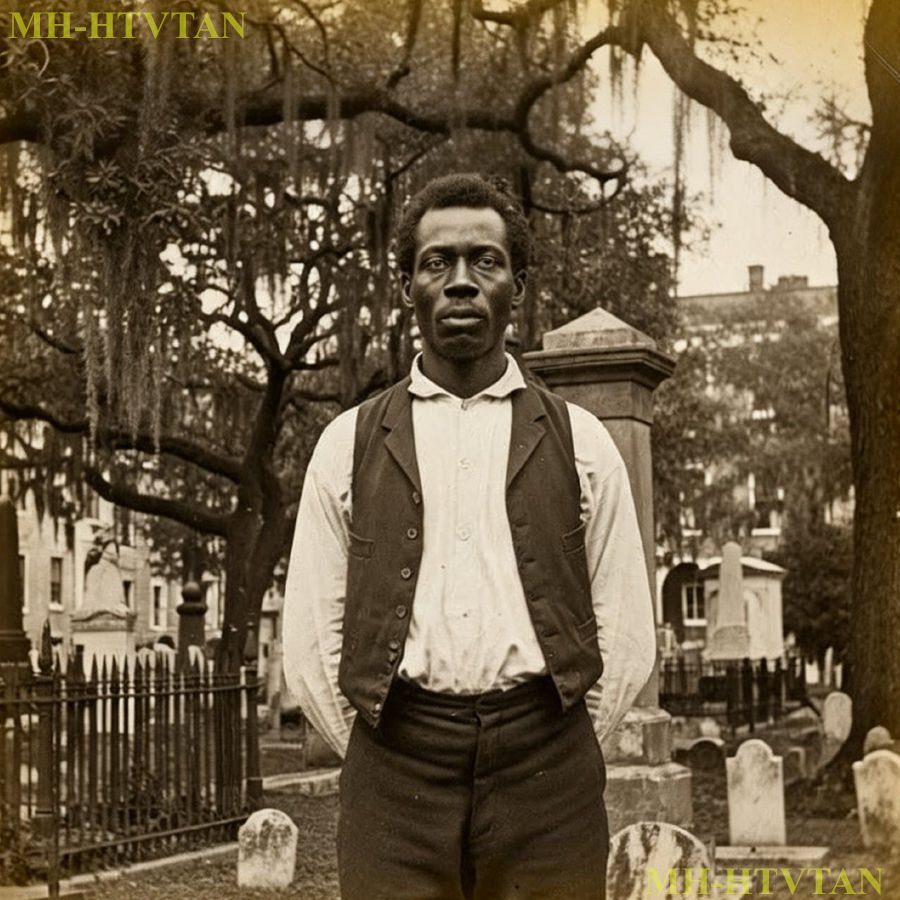

Solomon had been purchased specifically for Dr. Haway’s practice after demonstrating remarkable skills in botanical medicine. Skills that had been passed down through generations of his family who had served as healers on various plantations throughout the Carolina low country. Solomon Fairfax was not the typical field slave that populated Charleston’s plantations.

Standing tall with intelligent eyes that seemed to catalog every detail of his surroundings. He had been educated alongside the children of his previous master, learning to read and write before such education was strictly forbidden. His knowledge of Latin medical terms impressed even Dr. Hatheraway, who had come to rely heavily on Solomon’s ability to prepare complex compounds and assist with delicate procedures.

The wealthy patients who visited Hatheraway’s practice grew comfortable with Solomon’s presence, often requesting him specifically for his gentle bedside manner and seemingly intuitive understanding of their ailments. But Solomon’s life had not always been confined to the sterile walls of a medical practice. For 32 years before coming to Dr. Haway.

He had lived on the Pembbertton plantation 15 mi outside Charleston, where he had married a woman named Celia and raised three children, two boys and a girl, in one of the plantations slave quarters. The Petans had allowed this arrangement because Solomon’s healing skills proved invaluable during the frequent outbreaks of fever and disease that could devastate a plantation’s workforce overnight.

Solomon’s expertise had saved countless lives, both slave and free, earning him a measure of respect unusual for someone in his position. He had developed treatments for everything from snake bites to consumption, using a combination of traditional African remedies passed down from his grandmother and new techniques he learned by carefully observing the white physicians who occasionally visited the plantation.

The Petanss had even allowed him to tend to their own family during times of illness, a privilege that demonstrated the genuine trust they placed in his abilities. However, this relative comfort ended abruptly in March of 1851, when Edmund Peton’s gambling debts forced him to sell portions of his human property to cover his mounting financial obligations.

The sale was to include Solomon’s wife and children whowould be separated and sent to different plantations across the state, a common practice that plantation owners justified as business necessity, but which destroyed families as effectively as any natural disaster. Solomon had pleaded with Edmund Peton, offering to work additional years without any compensation if his family could remain together.

He had even suggested alternative arrangements, perhaps hiring himself out to other plantations during peak seasons to generate additional income. But Peton, facing creditors who demanded immediate payment, refused all negotiations. The sale was scheduled for March 14th, 1851 at the Charleston slave market, and nothing would change that decision.

The morning of March 14th dawned gray and humid with storm clouds gathering over the Ashley River as if nature itself sensed the tragedy about to unfold. Solomon had spent the previous night holding his family close in their small cabin, memorizing every detail of their faces, every sound of their breathing, knowing that sunrise would bring permanent separation.

Celia, his wife of 15 years, had maintained her composure throughout the ordeal. focusing her energy on preparing their children for what lay ahead. 8-year-old Marcus, the eldest, had inherited Solomon’s intelligence and curiosity about the world beyond the plantation. 6-year-old Samuel possessed his father’s gentle nature and natural affinity for healing, often helping Solomon gather medicinal plants from the woods surrounding their quarters.

Their daughter, four-year-old Grace, clung to her mother with the instinctive understanding that something terrible was about to happen, though she could not comprehend the full scope of what awaited them. As the slave traders arrived to collect their human cargo, Solomon watched helplessly as his family was loaded into a wagon alongside six other families being torn apart by Edmund Peton’s financial desperation.

The children’s tears mixed with their parents’ desperate promises that they would find each other again somehow someday. Promises everyone knew were lies designed to ease unbearable pain. But the true horror began during the journey to Charleston’s slave market. Halfway to the city, one of the wagon wheels struck a deep rut in the rain soaked road, causing the vehicle to tip precariously.

In the confusion that followed, Celia fell from the wagon, striking her head against a sharp rock embedded in the roadside. Blood immediately began flowing from the wound, and Solomon, despite his shackled hands, tried desperately to reach her. The slave traders, concerned only with delivering their cargo in celible condition, made a decision that would haunt Solomon for the rest of his life.

Rather than seeking medical attention for Celia, they declared her a loss and ordered the wagon to continue without her. Solomon screamed and fought against his restraints as they left his wife bleeding and unconscious by the roadside. But the other slaves held him back, knowing that resistance would only result in punishment for everyone.

The nightmare intensified at the Charleston slave market, where Solomon was forced to watch as his children were sold to separate buyers. Marcus was purchased by a rice planter from Georgetown who specialized in using child labor for the dangerous work of tending irrigation systems in alligatorinfested swamps. Samuel was bought by a cotton farmer from the upount whose reputation for working slaves to death was well known throughout the region.

Grace, too young for fieldwork, was sold to a family in Savannah as a house servant, disappearing forever into the vast network of human bondage that connected southern cities. Through all of this, Solomon maintained an outward appearance of resignation, knowing that any display of emotion or resistance would make his situation even worse.

Inside, however, something fundamental had broken. The man who had dedicated his life to healing, to preserving life and easing suffering, watched as everything he loved was destroyed by the casual cruelty of men who viewed human beings as property to be liquidated when convenient. Dr. Hatheraway, unaware of the full scope of Solomon’s tragedy, purchased him primarily for his medical skills, paying a premium price that reflected Solomon’s reputation as an exceptional healer.

The doctor had heard about Solomon’s abilities from other physicians who had witnessed his work at the Pembbertton plantation, and he desperately needed someone with advanced knowledge of medicinal compounds to help with his growing practice. As Solomon was led away from the slave market to begin his new life as Dr.

Hatheraway’s assistant, he cast one final look back at the place where his family had been scattered to the winds. In that moment, something cold and calculating settled into his heart. A patience that would allow him to wait, to learn, and eventually to make those responsible pay a price that matched the enormity oftheir crimes.

That evening, alone in the small room above Dr. Hatheraway’s practice that would serve as his new quarters, Solomon began writing in a leather journal he had managed to keep hidden throughout the ordeal. His first entry, written by candle light in the careful script he had learned as a child, began with words that would define the next four years of his life.

Today I watched my wife and children burn, and I did nothing to stop it. But I’m still alive, and I remember every face, every name, every voice that laughed as my world ended. They think they have broken me, but they have only taught me patience. The months following Solomon’s arrival at Dr. Hatheraway’s practice passed in a blur of routine medical procedures and careful observation.

Solomon performed his duties with the same quiet competence he had always shown, mixing compounds, preparing treatment rooms, and assisting with patient care. But beneath this facade of acceptance, he was conducting an entirely different kind of study, learning the intimate details of Charleston’s medical community and the wealthy families who comprise Dr.

Hatheraway’s clientele. Dr. Hatheraway, a widowerower in his 50s with no children of his own, had come to rely heavily on Solomon’s expertise. The doctor suffered from arthritis that made precise work increasingly difficult, and Solomon’s steady hands and encyclopedic knowledge of medicinal preparations had become indispensable to the practice.

More importantly, for Solomon’s developing plans, Dr. Haway had begun allowing him to handle certain patient interactions independently, particularly when dealing with chronic conditions that required regular monitoring and treatment. Charleston’s wealthy elite, accustomed to the finest medical care available, initially viewed Solomon with the typical mixture of casual indifference and condescending approval that characterized their interactions with skilled slaves.

However, his obvious competence and respectful demeanor gradually earned him a level of trust that would prove crucial to his plans. Patients began requesting him specifically, praising his gentle touch and apparent intuitive understanding of their conditions. During this period, Solomon methodically researched the backgrounds of every wealthy family that visited the practice.

He learned about their business dealings, their social connections, and most importantly, their involvement in the slave trade that had destroyed his family. Through careful listening and discreet inquiries among other slaves who worked in Charleston’s grand houses, he compiled detailed information about the men who had participated in or profited from the auction that scattered his children across the South.

His investigation revealed that Edmund Peton had been merely one link in a much larger chain of exploitation. The Charleston slave market operated with the support and participation of the city’s most respected citizens. Men who served on church boards and charitable committees while simultaneously treating human beings as livestock to be bought and sold for profit.

These were the men who attended elegant dinner parties to discuss literature and philosophy while their wealth was built on the suffering of families like Solomon’s. Among Dr. Hathaway’s regular patients, Solomon identified nine men who had direct connections to his family’s destruction. Some had been present at the auction, bidding on human cargo with the same detached interest they might show when purchasing horses or cattle.

Others had provided financial backing for the slave trading operation, lending money to dealers who specialized in breaking up families to maximize profits. A few had purchased slaves from the same auction that had sold his children, contributing to the system that treated human beings as disposable commodities. As 1851 progressed into 1852, Solomon began experiencing what he privately called his education in advanced chemistry.

Uh Dr. Hatheraway’s medical library contained numerous texts on pharmaceutical compounds, including detailed descriptions of various substances that could produce paralysis, unconsciousness, or the appearance of death while leaving the victim’s mind fully aware. These books written for legitimate medical purposes became Solomon’s textbooks in a curriculum of revenge.

The most significant discovery came in a treatise on South American plant toxins which described a compound derived from a vine that grew in the Amazon basin but had been successfully cultivated in the greenhouse of a Charleston botonist who supplied exotic specimens to wealthy collectors. This particular toxin, when properly prepared, could induce a state of complete muscular paralysis while leaving the victim’s consciousness and pain sensation entirely intact.

The affected person would appear dead to casual observation, but would remain fully aware of their surroundings for several hours before the toxin’s effects proved fatal. Solomon spent monthslearning to identify and cultivate the plant, eventually locating specimens in the greenhouse of Dr. Haway’s friend, Professor Nathaniel Krenshaw, who taught natural sciences at the College of Charleston.

Professor Krenshaw, unaware of Solomon’s true interest in botany, was delighted to find someone who shared his passion for exotic plant species and began allowing Solomon to help maintain his greenhouse collection. Through careful experimentation with laboratory mice, Solomon determined the precise dosage needed to achieve the desired effects.

Too little would merely cause temporary weakness. Too much would result in immediate death, but the correct amount would create a state indistinguishable from death to anyone lacking extensive medical knowledge, while preserving the victim’s consciousness long enough to experience the terror of being buried alive. The psychological preparation for what he planned required perhaps even more discipline than mastering the chemistry involved.

Solomon had to maintain his gentle, helpful demeanor while internally preparing himself to watch men suffer in ways that violated everything his healing nature represented. He justified this transformation by regularly reviewing the names of his children in his journal, reminding himself of their fate and the callous indifference of the men who had profited from their sale.

As winter approached in 1852, Solomon had identified his first target, Colonel Reginald Fitzpatrick, a wealthy rice planter who had not only attended the auction where Solomon’s family was sold, but had loudly joked about the breeding potential of the children being offered for sale. Fitzpatrick suffered from chronic gout and visited Dr.

Hathaway’s practice monthly for treatments that provided temporary relief from his painful condition. The colonel’s regular appointments, his trust in Solomon’s medical abilities, and his habit of arriving alone for his treatments made him an ideal first victim for Solomon’s carefully planned campaign of revenge. But Solomon forced himself to wait, knowing that patience and perfect execution would be essential to avoiding suspicion and ensuring that all nine men received the justice they deserved.

In his journal, Solomon wrote detailed profiles of each intended victim, noting their medical conditions, their treatment schedules, and their involvement in the slave trade. These entries read like a physician’s case notes. But they documented a very different kind of treatment plan. One designed not to heal, but to ensure that nine men would experience the same helpless terror that Solomon’s children had felt as they were torn from everything they had ever known.

The transformation of Solomon Fairfax from healer to methodical killer began with meticulous preparation that spanned the entire year of 1852. Every detail had to be perfect, every contingency planned, every variable controlled. The men he intended to target were not isolated individuals, but pillars of Charleston society, whose deaths would be scrutinized by the city’s most prominent physicians, and investigated by authorities, who would be under intense pressure to find explanations.

Solomon’s first step involved establishing himself as an indispensable part of Dr. Haway’s practice. He began arriving earlier each morning to prepare the office, staying later each evening to organize medical supplies and demonstrating such dedication to his work that Dr. Hatheraway increasingly relied on his judgment in medical matters.

This growing trust would be essential when Solomon needed to handle certain patients independently without the doctor’s direct supervision. The development of his paralytic compound required months of careful refinement. Working in a small shed behind Dr. Hathaway’s office, ostensibly to prepare herbal remedies that supplemented the doctor’s treatments, Solomon cultivated the toxic vine and experimented with extraction methods.

The process was dangerous. Several times he accidentally exposed himself to small amounts of the toxin, experiencing temporary numbness that gave him a terrifying preview of what his victims would endure in their final hours. The compound in its final form was a colorless, odorless liquid that could be easily mixed with other medications without detection.

When administered in the correct dosage, it would begin taking effect within 30 minutes, initially causing weakness and disorientation that would be attributed to the patients existing medical condition. Within an hour, complete paralysis would set in, but the victim would remain conscious and able to hear, see, and feel everything happening around them.

Most crucially, the paralysis would be so complete that it would be impossible to detect breathing or pulse without extremely careful examination. To physicians of the 1850s, lacking modern diagnostic equipment, a patient treated with Solomon’s compound, would appear to have died peacefully from natural causes.

Only someone withextensive knowledge of the toxin’s properties would recognize the subtle signs that indicated the victim was still alive, but completely immobilized. Solomon’s selection of Colonel Reginald Fitzpatrick as his first victim was both strategic and personal. Fitzpatrick’s monthly visits for gout treatment provided a predictable schedule, and his arrogant demeanor made him particularly easy to despise.

More importantly, Fitzpatrick lived alone except for house slaves who were terrified of him, making it unlikely that anyone would insist on an extended wake or detailed examination of his body after death. The colonel’s medical history provided Solomon with the perfect cover story. Fitzpatrick suffered not only from gout, but also from a weak heart, a condition that Dr.

Hatheraway had been monitoring for several years. If Fitzpatrick died suddenly, heart failure would be the obvious diagnosis, requiring no further investigation or autopsy. On December 15th, 1852, Colonel Fitzpatrick arrived for his regular appointment, complaining that his gout pain had worsened significantly over the past week. Dr.

Hathaway was attending to another patient, so he instructed Solomon to prepare Fitzpatrick’s usual treatment and begin the consultation. This routine delegation of responsibility provided exactly the opportunity Solomon had been waiting for. As Solomon prepared the colonel’s medication, he added precisely measured drops of his paralytic compound to the solution.

Years of medical practice had taught him to maintain steady hands and a calm expression even in stressful situations. Skills that served him well as he crossed the line from healer to killer. Fitzpatrick, accustomed to receiving treatments from Solomon, consumed the medication without question or hesitation.

The conversation that followed would be burned into Solomon’s memory forever. As the toxin began taking effect, and Fitzpatrick started feeling weak, Solomon sat beside the colonel’s chair and spoke in the same gentle tone he had always used with patience. Colonel Fitzpatrick,” Solomon said quietly.

“I want you to know that my name is Solomon Fairfax, and you destroyed my family at the slave auction on March 14th, 1851. You laughed when my children were sold. You joked about their value as breeding stock. Do you remember that day?” Fitzpatrick’s eyes, already glazing over from the advancing paralysis, showed a flicker of recognition and then growing horror as he realized what was happening.

He tried to speak to call for help, but found that his voice had been stolen along with his ability to move. Solomon continued speaking in that same calm, professional tone. You’re not dying yet, Colonel. The medicine I gave you has paralyzed every muscle in your body, but your mind is completely clear. You can hear every word I’m saying.

You can feel everything that’s happening to you. In about an hour, Dr. Hathaway will examine you and pronounce you dead from heart failure. Your body will be prepared for burial, and tomorrow evening, you’ll be placed in your coffin and buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery.” Solomon leaned closer, ensuring that Fitzpatrick could see his face clearly.

But you won’t actually die until several hours after you’re buried. You’ll be completely aware as the dirt is shoveled onto your coffin. You’ll hear every sound, feel every sensation, and have plenty of time to think about what you did to my children. That’s when you’ll understand what terror really feels like. The paralysis was now complete.

Fitzpatrick appeared to be a corpse, but Solomon could see the desperate awareness in his eyes, the frantic effort to somehow communicate or escape his immobilized body. Solomon checked the colonel’s pulse and breathing with professional thoroughess, confirming that both were so faint as to be undetectable without specialized instruments. When Dr.

Haway entered the treatment room 5 minutes later. He found Solomon standing respectfully beside what appeared to be Colonel Fitzpatrick’s body, his expression showing appropriate concern and sadness. I’m afraid the colonel has passed, doctor. Solomon reported quietly. His heart gave out while I was preparing his next treatment.

He seemed to go very peacefully. Dr. Hathaway’s examination confirmed Solomon’s diagnosis. The colonel showed no signs of life and given his known heart condition. The cause of death seemed obvious. Within an hour, the body was removed to Fitzpatrick’s mansion, where arrangements were made for a funeral, befitting one of Charleston’s most prominent citizens.

Solomon attended the funeral, standing respectfully in the section designated for slaves, while Colonel Fitzpatrick’s coffin was lowered into the ground. As the first shovel fulls of dirt struck the wooden lid, Solomon wondered if Fitzpatrick was still conscious, still aware of what was happening to him. The thought brought him no satisfaction, only a cold sense of justice finally being served.

Thatevening, Solomon made the second entry in his journal. Colonel Fitzpatrick has paid for his crimes. Eight more remain. Justice is patient, but it is also certain. The months following Colonel Fitzpatrick’s burial passed with agonizing slowness, as Solomon waited to see if his method had aroused any suspicion. Charleston’s social circles buzzed with the expected condolences and remembrances of the colonel’s contributions to the community, but no questions were raised about the circumstances of his death. Dr.

Haway mentioned the case to other physicians as an example of how quickly heart failure could claim even seemingly healthy individuals. And Solomon’s reputation as a skilled and caring medical assistant remained untarnished. This successful execution of his first revenge gave Solomon confidence to proceed with the second phase of his plan.

But it also forced him to confront the psychological toll of what he was doing. Despite years of careful preparation and absolute certainty about the justice of his cause, actually watching a man die in terror had affected him more deeply than expected. He found himself unable to sleep for weeks afterward, not from guilt, but from the vivid imagination of what Fitzpatrick had experienced in those final hours buried alive.

The selection of his second victim required careful consideration of timing and method. Solomon needed to avoid establishing any pattern that might eventually attract attention, which meant varying both the intervals between deaths and the apparent causes. His research had identified Judge Marcus Calverton as an ideal second target.

A man who had not only witnessed the sale of Solomon’s family, but had provided legal justification for the separation of slave families, arguing in court that such practices were essential for maintaining order and maximizing economic efficiency. Judge Calverton suffered from severe migraines that had grown progressively worse over the past 2 years, forcing him to seek treatment from Dr.

Haway on an increasingly frequent basis. The judge’s condition provided Solomon with both opportunity and cover. Migraine sufferers were known to occasionally suffer fatal strokes, and Calvertton’s advanced age made such an outcome medically plausible. But before Solomon could implement his plan against Judge Calverton, an unexpected complication arose that nearly derailed his entire campaign of revenge.

In March of 1853, Dr. Dr. Hatheraway announced that he was considering taking on a junior partner, a young physician named Dr. Timothy Henderson, who had recently completed his medical training in Philadelphia and was eager to establish himself in Charleston’s competitive medical community. Dr. Henderson’s addition to the practice would mean increased scrutiny of Solomon’s activities, more witnesses to his interactions with patients, and greater difficulty in administering his paralytic compound without detection.

Even more concerning, Dr. Henderson had trained under physicians who were familiar with the latest advances in forensic medicine, including techniques for detecting unusual substances in deceased patients. Solomon realized that he would need to accelerate his timeline significantly. Rather than spacing his victim’s deaths over several years as originally planned, he would need to complete his mission within months before Dr.

Henderson’s presence made continued operations impossible. This compression of his schedule would require him to take greater risks and accept less than perfect conditions for some of his planned murders. The pressure to move quickly led Solomon to his first serious mistake. While preparing for Judge Calverton’s treatment in April 1853, Solomon accidentally used a slightly higher dose of his paralytic compound than intended.

The judge’s apparent death occurred more rapidly than expected, and the intensity of the paralysis was so complete that even Dr. Hatheraway noticed something unusual about the body’s condition. Strange, Dr. Hatheraway murmured as he examined Judge Calverton’s corpse. The muscle rigidity seems more pronounced than typical for stroke victims. And look at his eyes.

There’s something almost desperate about their expression. Solomon’s heart raced as he watched Dr. Hathaway conduct a more thorough examination than he had performed on Colonel Fitzpatrick. For several terrifying minutes, Solomon feared that his entire plan was about to be exposed. But Dr. Haway’s medical training, while thorough for its time, lacked the specific knowledge needed to recognize the effects of Solomon’s exotic toxin.

After 15 minutes of examination, the doctor concluded that the unusual symptoms were simply the result of Judge Calverton’s particularly severe stroke. “Poor man must have suffered terribly in his final moments,” Dr. Haway observed, unknowingly, describing exactly what Judge Calverton was experiencing at that very moment, paralyzed but conscious as his body was prepared for burial.

Judge Calverton’sfuneral was attended by even more prominent citizens than Colonel Fitzpatrick’s, as befitted a man who had served Charleston’s legal community for over 30 years. Solomon watched from the slave section as the judge’s coffin was lowered into St. Michael’s cemetery, just three rows away from where Colonel Fitzpatrick lay buried.

As the funeral concluded, Solomon noticed something that sent a chill through his blood. A young man standing near the back of the crowd, taking careful notes in a small leather book. The notetaker was Thomas Grimby, a journalist for the Charleston Mercury, who had begun investigating what he privately called the prominent deaths phenomenon.

a series of sudden fatalities among the city’s elite that seemed statistically unlikely. Grimby had noticed that over the past 6 months, Charleston had lost several wealthy citizens, to unexpected medical emergencies, all under circumstances that were medically explainable, but collectively suspicious. Solomon’s journal entry for that evening reflected his growing awareness that time was running out.

Judge Calverton has joined Colonel Fitzpatrick in experiencing true justice. But I fear that others are beginning to notice patterns that could threaten the completion of my mission. I must work faster, even if it means accepting greater risks. The acceleration of Solomon’s timeline meant that his third victim would need to be eliminated within weeks rather than months.

He selected Captain William Dandridge, a ship owner who had transported slaves from Charleston to markets throughout the South and who had personally supervised the loading of human cargo with the same attention to detail he showed when handling valuable cotton shipments. Captain Dandridge presented unique challenges as a target. Unlike the previous victims who had visited Dr.

to Hatheraway’s office regularly for chronic conditions. Dandridge was generally healthy and only sought medical attention for minor injuries sustained during his maritime activities. Solomon would need to create an opportunity rather than waiting for one to occur naturally. The solution came through Solomon’s network of contacts among Charleston’s slave community.

Kitchen slaves who worked in the grand houses along the battery often gathered information about their master’s activities and shared it with slaves from other households. Through these informal intelligence networks, Solomon learned that Captain Dandridge was planning a dinner party for prominent members of Charleston’s shipping community scheduled for May 20th, 1853.

The dinner party would provide Solomon with the perfect opportunity to eliminate his third victim while simultaneously gathering intelligence about potential future targets. Kitchen staff for such events were often borrowed from other households, and Solomon had established friendships with several slaves who worked in food preparation.

With careful planning, he could arrange to assist with serving the dinner, giving him direct access to Captain Dandridge and his guests. But even as Solomon refined his plans for the dinner party, Thomas Grimby was conducting his own investigation into Charleston’s recent string of prominent deaths. The journalist had begun visiting St.

Michael’s Cemetery regularly, noting the locations of recent burials and documenting the medical histories of the deceased. What he discovered would soon threaten everything Solomon had worked to accomplish. Just when we thought we’d seen it all, the horror in Charleston intensifies. If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries.

Hit that like button to support our content. And don’t forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this. Let’s discover together what happens next. The evening of May 20th, 1853 marked the beginning of the end for Solomon Fairfax’s methodical campaign of revenge. The dinner party at Captain Dandridge’s mansion on East Bay Street brought together 12 of Charleston’s most influential shipping merchants, creating an unprecedented opportunity for Solomon to study multiple potential victims while eliminating his primary target.

Solomon had arranged his participation through Martha, an elderly slave who supervised kitchen operations for many of Charleston’s grandest social events. Martha, unaware of Solomon’s true intentions, was grateful for his offer to help serve the elaborate meal, as several of her regular assistants had fallen ill with a fever that was spreading through the slave quarters of the French Quarter.

The captain’s dining room gleamed with crystal and silver as Charleston’s maritime elite gathered to discuss the expansion of shipping routes and the increasing profitability of human cargo transport. Solomon moved through the room with practiced invisibility, refilling wine glasses and clearing plates while listening to conversations that revealed the casual brutality underlying Charleston’s economic prosperity.

Captain Dandridge, a robust man in his early 50s with graying hair and weathered hands that spoke of decades spent at sea, held court at the head of the table, regailing his guests with stories of profitable voyages and strategies for maximizing the value of slave shipments. His detailed knowledge of techniques for preventing slave rebellions during transport and methods for keeping human cargo alive during long voyages made him particularly contemptable in Solomon’s eyes.

As the evening progressed, Solomon identified several other men whose involvement in the slave trade marked them as future targets. The conversations he overheard revealed a network of complicity that extended far beyond the individual traders who had participated in his family’s sale. These men discussed human beings with the same detached interest they showed for cotton prices or shipping schedules, viewing the destruction of families as an acceptable cost of conducting business.

Solomon’s opportunity came during the serving of the final course, a elaborate dessert that required individual preparation for each guest. Working in Captain Dandridge’s kitchen, Solomon carefully added his paralytic compound to the captain’s portion of brandy soaked cake, using a method he had perfected through months of experimentation.

The toxin was absorbed into the alcohol- soaked dessert, masking any potential taste while ensuring rapid absorption into the victim’s system. Captain Dandridge consumed his dessert with obvious enjoyment, complimenting Martha on her exceptional preparation and requesting the recipe for his own cook.

Within 30 minutes, he began experiencing the initial effects of Solomon’s compound, a slight dizziness that he attributed to the evening’s wine consumption and the warmth of the crowded dining room. As the paralysis progressed, Captain Dandridge excused himself from the table, claiming that he needed fresh air to clear his head. Solomon, observing from the kitchen doorway, watched as the captain made his way to his private study, where he collapsed into his favorite leather chair just as the toxin reached full effect. The discovery of Captain

Dandridge’s death 20 minutes later created exactly the kind of scene Solomon had hoped to avoid. Instead of dying quietly in the privacy of Dr. Hatheraway’s office, the captain had expired in front of 12 witnesses who immediately began demanding answers. Dr. Samuel Pettigrew, one of the dinner guests, examined the body while the others looked on with growing alarm.

“This is most peculiar,” Dr. Pedigrew announced after his initial examination. “Captain Dandridge appears to have suffered some form of seizure, but there are no obvious symptoms of apoplelexy or heart failure. The muscle rigidity is quite pronounced, almost as if he had been poisoned.

” The word poisoned sent a shock through the assembled guests and created exactly the kind of attention Solomon had been working to avoid. Within an hour, two additional physicians had been summoned to examine Captain Dandridge’s body, and by morning, news of the suspicious death had spread throughout Charleston social circles.

Thomas Grimby, the journalist who had been tracking the series of prominent deaths, arrived at Captain Dandridge’s mansion before dawn, interviewing servants and guests while the details of the evening were still fresh in their memories. His investigation revealed that Solomon had been present at the dinner party, marking the first time that any individual could be connected to multiple recent deaths of Charleston’s elite.

The net was closing around Solomon, but his mission remained incomplete. Six of his intended victims were still alive, and the increasing scrutiny made it unlikely that he would have opportunities to eliminate them using his established methods. Desperation and the knowledge that his time was running out led Solomon to make the most dangerous decision of his campaign.

He would attempt to kill multiple targets simultaneously, using a method that would ensure maximum terror, even if it meant exposing himself to almost certain capture. Solomon’s research had identified a private meeting scheduled for June 15th, 1853, when six of Charleston’s most prominent slave traders would gather at the offices of Henderson and Associates to finalize contracts for a major expansion of their operations.

The meeting would take place in the evening after normal business hours, providing Solomon with an opportunity to trap all six men in a confined space. The plan he developed was both ingenious and terrifying in its simplicity. Working at night over the course of two weeks, Solomon used his access to medical supplies to prepare a large quantity of his paralytic compound in a highly concentrated form.

Instead of administering the toxin individually to each victim, he would introduce it into the building’s air supply using the gas lighting system that illuminated the office. The Henderson and Associates buildingemployed a central gas distribution system that fed individual lamps throughout the structure.

By injecting his concentrated toxin into the main gas line, Solomon could ensure that everyone in the building would be exposed to lethal doses of the compound within minutes of the lamps being lit for the evening meeting. On the night of June 15th, Solomon positioned himself in the alley behind the Henderson and Associates building, waiting for the six men to arrive for their clandestine meeting.

At exactly 8:00, the office windows began glowing with gas lamplight, indicating that the meeting had begun and Solomon’s trap was being activated. Within 30 minutes, the building fell silent. Solomon waited another hour to ensure that the paralysis had taken complete effect before using a duplicate key he had obtained through careful planning to enter the building through the rear entrance.

The scene that greeted him in the main conference room was both horrifying and satisfying. Six men sat around a mahogany table, their bodies frozen in the positions they had occupied when the paralysis struck. Their eyes, the only part of their anatomy still capable of movement, tracked Solomon as he moved around the room, revealing the terror and awareness trapped within their immobilized bodies.

Solomon approached each man individually, speaking in the same calm, professional tone he had used with his previous victims. He identified himself and explained exactly what was happening to them, describing in clinical detail how they would remain conscious throughout their burial and the hours of suffocation that would follow.

The expressions in their eyes, panic, disbelief, desperate attempts to communicate provided Solomon with a satisfaction that years of planning had not prepared him to experience. But Solomon’s moment of triumph was short-lived. As he prepared to leave the building and allow the victims to be discovered the following morning, he heard footsteps in the corridor outside the conference room.

Someone else was in the building, someone who was not supposed to be there, according to Solomon’s careful surveillance of the meeting. The door opened to reveal Thomas Grimby, the journalist who had been investigating Charleston’s recent string of suspicious deaths. Grimby had been following leads that pointed to tonight’s meeting as a crucial piece of his investigation, and he had arrived just in time to witness Solomon standing over six apparently dead bodies.

“So, it’s true,” Grimby said quietly, his voice showing a mixture of horror and vindication. “Someone has been systematically murdering Charleston’s elite, and you’re the one responsible.” Solomon realized that his careful plans had finally unraveled completely. There was no way to explain his presence in the room, or the convenient death of six men who had been his targets.

The journalist’s investigation had led him to the same conclusion that would soon be reached by Charleston’s authorities. Someone with access to medical knowledge and detailed information about the victim’s schedules had been conducting a methodical campaign of murder. “They destroyed my family,” Solomon said simply, making no attempt to deny his responsibility.

They sold my children like cattle and left my wife to die by the roadside. This is justice, not murder. Grimby’s response revealed the complexity of Charleston’s racial dynamics, even in the face of obvious crime. As a journalist, he was committed to exposing the truth about the murders. As a Southerner, he understood the brutal realities of the slave system that had motivated Solomon’s revenge.

The conflict between these perspectives created a moment of hesitation that would determine both men’s fates. “Those men in there,” Grimby said, gesturing toward the paralyzed victims. “They’re still alive, aren’t they? That’s why their eyes are moving. You’ve done something to them that makes them appear dead while keeping them conscious.

” Solomon nodded, seeing no point in denying what was obviously true. They’ll experience exactly what my children felt when they were torn away from everything they knew. They’ll have hours to think about what they did, just as my family had hours to contemplate their fate during that wagon ride to the slave market.

The conversation that followed would be recorded in Grimby’s own journal discovered decades later during the renovation of his former residence. The journalist found himself caught between his professional obligation to expose a mass murderer and his human understanding of the injustices that had created that murderer. “I can’t let you continue,” Grimby said finally.

“But I also can’t ignore what drove you to this. Those men participated in a system that treats human beings as property. They profited from breaking up families and selling children. In any just society, they would face consequences for those actions. Solomon’s response revealed the philosophical framework that hadsustained him through four years of planning and execution.

In a just society, my family would never have been destroyed in the first place. Since justice was denied to us through legal means, I created my own justice through the knowledge that their system taught me. The standoff between Solomon and Grimby was interrupted by the sound of approaching voices outside the building.

Other people were coming to investigate the meeting, either because they had been expected to attend or because someone had noticed unusual activity in the building. Both men realized that within minutes the scene would be discovered and Solomon’s fate would be sealed. “There’s a back stairs,” Grimby said quietly. “You could still escape.

I could delay reporting this for a few hours, give you time to reach the countryside. But Solomon had already accepted that his mission would end with his capture or death. Nine men had been responsible for his family’s destruction, and he had managed to eliminate only six. The remaining three would live to profit from their crimes, and the system that had created those crimes would continue unchanged.

I’m not running, Solomon said with the same calm certainty that had characterized all his actions. Let them come. Let them discover what I’ve done. Maybe when this story spreads, other people will understand that even slaves have limits to what they’ll endure in silence. The voices outside grew louder, accompanied by the sound of multiple footsteps on the building’s front stairs.

Grimby made a decision that would haunt him for the rest of his life. He chose to protect his story rather than protect Solomon. The journalist positioned himself to observe and document what happened next, ensuring that he would be able to provide a complete account of Solomon’s capture and the discovery of his victims.

When Charleston’s city constables burst into the conference room, they found a scene that defied immediate explanation. Six prominent citizens sat motionless around a conference table, apparently dead, but showing none of the typical signs of natural death. Standing calmly beside the table was a slave who made no attempt to flee or resist arrest, instead offering a complete confession of his actions and a detailed explanation of his methods.

Solomon’s confession, recorded by the chief constable and preserved in Charleston’s criminal archives, provided authorities with information that solved not only the evening’s multiple deaths, but also the mysterious fatalities that had puzzled the city’s medical community for nearly 2 years. the paralytic compound, the method of administration, the selection of victims based on their involvement in slave trading.

Everything was documented with the same methodical precision that had characterized Solomon’s campaign of revenge. The trial of Solomon Fairfax became one of the most controversial legal proceedings in Charleston’s antibbellum history, not because of any doubt about his guilt, but because of the moral questions his case raised about slavery, justice, and the limits of human endurance.

The prosecution, led by District Attorney Charles Rutled, presented the case as a simple matter of murder. a slave who had killed nine prominent citizens and must be executed to maintain social order. The defense appointed by the court and led by the reluctant attorney Benjamin Crawford faced the nearly impossible task of defending a client who had confessed to multiple murders while arguing that those murders were justified by the systematic destruction of his family.

Crawford’s strategy focused not on denying Solomon’s guilt, but on exposing the brutal realities of the slave system that had created the conditions for such desperate revenge. The trial revealed details about Charleston’s slave trade that had previously been hidden from public view. Testimony about the methods used to separate families, the casual cruelty of slave auctions, and the complete legal powerlessness of enslaved people created an uncomfortable mirror for a society that preferred to view slavery as a benevolent institution. Solomon’s

detailed testimony about watching his family destroyed while being unable to intervene forced Charleston’s elite to confront the human consequences of their economic system. Thomas Grimby’s coverage of the trial for the Charleston Mercury created a sensation throughout the South.

His articles, which included extensive excerpts from Solomon’s Journal and detailed descriptions of the paralytic compound, were reprinted in newspapers from Virginia to Louisiana. The story of the slave who had turned his medical knowledge into an instrument of revenge became a source of fascination and terror for slave owners throughout the region.

The medical aspects of Solomon’s crimes received particular attention from the scientific community. Dr. Hatheraway, devastated to learn that his trusted assistant had used the practice as a base for murder, provided detailed testimony aboutSolomon’s pharmaceutical knowledge and access to exotic compounds. The revelation that slaves could possess sophisticated understanding of chemistry and toxicology challenged prevailing assumptions about their intellectual capabilities and sparked debates about the wisdom of educating enslaved people.

The six men who had been paralyzed in the Henderson and Associates building provided the most dramatic testimony of the trial. All had survived their ordeal, though their experiences varied in horror depending on how long each had remained conscious after their apparent death.

Their accounts of lying paralyzed while fully aware, hearing their own death pronounced, and funeral arrangements discussed created a visceral understanding of Solomon’s revenge that mere legal arguments could not convey. Colonel Harrison Vance, one of the survivors, described the psychological torture of his experience. I could hear everything, feel everything, but I could not move so much as an eyelid.

When my wife wept over my body, I wanted desperately to comfort her, to let her know I was still alive. But I was trapped inside my own corpse, completely helpless, while arrangements were made for my burial. If Solomon Fairfax had intended to show me what terror felt like, he succeeded beyond measure. The revelation that three of Solomon’s earlier victims, Colonel Fitzpatrick, Judge Calverton, and Captain Dandridge, had been buried while still alive, created a public outcry that extended far beyond Charleston’s boundaries.

Families throughout the South began questioning whether their own deceased relatives had actually died naturally or had been victims of similar poisoning. The demand for exumations and post-mortem examinations overwhelmed Charleston’s medical community and created a climate of suspicion that lasted for years. Solomon himself remained calm and articulate throughout the proceedings, showing no remorse for his actions, while expressing regret only that he had been unable to complete his mission against all nine of his intended

victims. His final statement to the court provided a chilling summary of his motivations and methods. I was trained to preserve life and ease suffering. But when this society destroyed my family while calling it legal and proper, I learned that the same knowledge used to heal can also be used to ensure justice.

I do not ask for mercy because no mercy was shown to my wife and children. I ask only that when you condemn me, you remember that I am not the one who created the system that makes such revenge necessary. The jury’s deliberation lasted less than an hour. Solomon Fairfax was found guilty on all counts and sentenced to death by hanging, a verdict that surprised no one given the magnitude of his crimes and the social necessity of maintaining order in a slaveholding society.

However, the speed of the conviction did not resolve the moral questions his case had raised about slavery, justice, and the humanity of enslaved people. Solomon was executed on October 15th, 1853 before a crowd of over 2,000 people who had gathered to witness the death of Charleston’s most notorious criminal.

His final words spoken from the gallows with the same calm certainty he had shown throughout his trial were recorded by Thomas Grimby and published in newspapers throughout the South. I die knowing that nine men experienced the terror my children felt when they were sold away from everything they loved. That knowledge makes my death worthwhile.

But this system that creates such desperation will continue and other families will suffer as mine did. When that happens, remember that even the most patient man has limits to what he will endure in silence. Solomon’s body was buried in an unmarked grave outside Charleston city limits in accordance with laws prohibiting the interament of executed criminals in consecrated ground.

But his journal, confiscated as evidence during the trial, was never returned to authorities after the proceedings concluded. Thomas Grimby, who had been allowed to examine the journal during his coverage of the trial, had made extensive copies of its contents before returning the original to the court clerk. Years later, when Grimby was preparing his memoirs, he decided to bury Solomon’s journal beneath the Magnolia tree in St.

Michael’s Cemetery near the graves of the men Solomon had killed. The journalist’s own account, written in 1889, explained his decision. I could not bear to destroy the record of such methodical revenge, but I also could not allow it to inspire others to similar actions. Perhaps future generations with different perspectives on justice and slavery will be better equipped to understand the terrible necessity that drove Solomon Fairfax to become both healer and killer.

The discovery of Solomon’s journal in 1923 during the cemetery renovation that revealed the scratch marks inside nine coffins provided the final confirmation of a story that had passed into legend. Thephysical evidence, the scratches made by fingernails desperately clawing at wooden coffin lids, proved that Thomas Grimby’s account had been accurate in every detail.

Charleston’s city government immediately classified the discovery as sensitive historical material and sealed all records related to the case. The official explanation cited concerns about public safety and the potential for racial tensions, but many believed the real motivation was protecting the reputations of prominent families whose ancestors had participated in or profited from the slave trade.

The legacy of Solomon Fairfax’s revenge extended far beyond Charleston’s boundaries. Throughout the antibbellum south, slave owners became increasingly suspicious of educated slaves, particularly those with medical knowledge or access to pharmaceutical compounds. New laws were passed restricting slaves access to books, medical training, and scientific knowledge as authorities recognized that education could transform the oppressed into dangerous opponents.

The case also influenced the development of forensic medicine in the United States. The exotic paralytic compound that Solomon had used prompted research into methods for detecting unusual toxins in deceased victims, leading to advances in post-mortem examination techniques that would prove valuable in future criminal investigations.

But perhaps the most significant impact of Solomon’s story was its effect on the national debate about slavery itself. The revelation that even the most seemingly dosile and loyal slaves might harbor years of accumulated rage challenged fundamental assumptions about the institution’s stability and moral justification. If a man like Solomon Fairfax, educated, skilled, and trusted by his masters, could plan and execute such methodical revenge, what did that say about the true feelings of the millions of other enslaved people throughout the South?

This mystery shows us that even in the darkest chapters of American history, individual acts of resistance could shake the foundations of seemingly unshakable systems. The story of Solomon Fairfax reminds us that justice delayed is not always justice denied. Sometimes it simply takes a different, more terrible form.

What do you think of this story? Do you believe that Solomon’s actions were justified by the destruction of his family? or was his revenge simply another form of evil? Leave your comment below and share your thoughts about this chilling tale from Charleston’s buried past. If you enjoyed this dark journey into America’s hidden history and want more stories that reveal the secrets our ancestors tried to forget, subscribe now, hit the notification bell, and share this video with someone who appreciates the complex truths that lie beneath our nation’s

official histories. Until next time, remember that the past is never truly buried. It’s always waiting to be discovered by those brave enough to dig.