In 1857, the port city of Savannah held secrets beneath its moss-draped oaks and cobblestone streets that would challenge everything the refined society believed about itself. Among the grand mansions of Bull Street and the bustling commerce of Factors Walk, a woman existed whose very presence would unravel the carefully constructed facade of southern gentility.

Her name recorded in fragmentaryary church documents and whispered in the margins of plantation ledgers was Sarah. The first official mention of her appears in the baptismal records of Christ Church where Reverend Marcus Whitfield noted in his precise handwriting the christristening of a child born to unnamed parents in 1832.

The entry discovered decades later during a renovation of the church archives contained an unusual addendum written in different ink. Child of extraordinary countenance placed in the care of the Peton household. What made this notation remarkable was not its content, but the fact that it had been deliberately obscured with India, Inc.

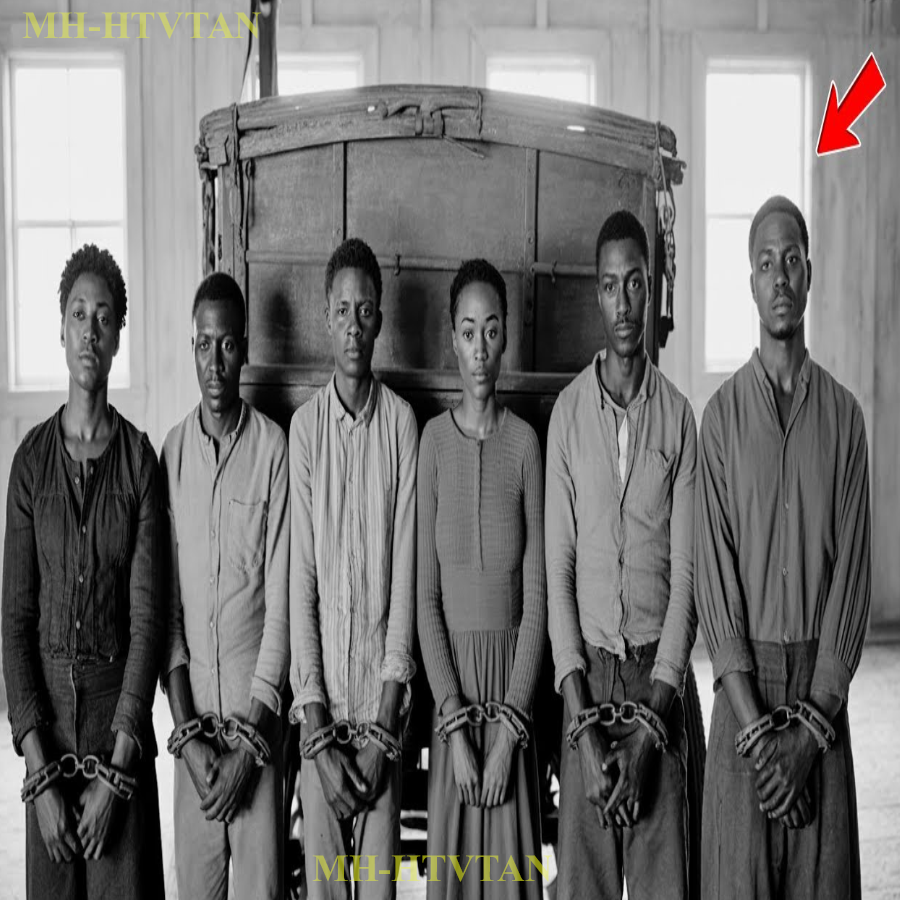

, as if someone had attempted to erase it from history. The Peton estate occupied 12 acres along the Savannah River, where Cornelius Peetton had built his fortune through rice cultivation and what he diplomatically referred to as human property management. The plantation books, meticulously maintained and later donated to the Georgia Historical Society, reveal that the Peetton household included 43 enslaved individuals by 1850.

Among these entries, one stands out for its peculiar lack of detail. Where other entries contained thorough descriptions of age, origin, skills, and physical characteristics, the notation for Sarah consisted of only a name and the designation house servant special considerations. Udit those who encountered Sarah during her years at the Peton estate would later struggle to articulate what made her presence so memorable.

Thomas Caldwell, a cotton merchant who frequently conducted business with Cornelius Peton, wrote in his personal correspondence to his brother in Charleston, “There exists in that house a woman whose appearance defies the natural order we have come to expect. She moves through the rooms as if the very air parts before her, and when she speaks, which is rarely, her voice carries an education that raises uncomfortable questions.

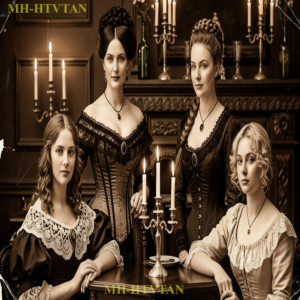

” The social structure of Antibbellum Savannah operated on rigid hierarchies that everyone understood but few dared to examine closely within the Peton household. However, these boundaries appeared to blur in ways that made visitors uneasy. Margaret Ashford, wife of a prominent attorney, mentioned in her diary that during a dinner party at the Peton estate, she observed Sarah serving wine with a grace that seemed almost choreographed. More disturbing to Mrs.

Ashford was the way Cornelius Peetton addressed her, not with the casual commands typically reserved for enslaved servants, but with a difference that suggested a relationship far more complex than ownership. Edmund Hartwell, the family physician, noted in his medical journal that he had been summoned to treat Sarah for what he described as a condition of nervous exhaustion brought on by excessive intellectual stimulation.

The doctor’s notes, preserved in his estate papers, reveal his bewilderment at finding medical texts in multiple languages hidden beneath Sarah’s sleeping quarters, along with correspondence that suggested she’d been conducting a secret education that far exceeded what was considered appropriate for any woman, regardless of station.

By 1854, rumors began circulating through Savannah’s social circles about the unusual dynamics within the Peton household. These whispers gained substance when doctor the turning point came in the spring of 1855 when Governor Johnson Witmore arrived in Savannah for the annual Confederate memorial celebration. Whitmore, a widowerower known for his passionate speeches about southern values and the divine order of society, was scheduled to stay at the Peetton estate during his visit.

The governor’s secretary, James Morrison, maintained a detailed log of official engagements that would later provide crucial evidence of what transpired during those 10 days. Morrison’s records, discovered in 1868 during the inventory of the governor’s papers following his mysterious resignation, paint a picture of a man whose carefully constructed world began to unravel from the moment he encountered Sarah.

The secretary noted that the governor’s behavior became increasingly erratic, cancelling official meetings and spending hours in what Morrison described as intense private conversations with the Peton House staff. More troubling were Morrison’s observations about the governor’s appearance, noting that Witmore began wearing his formal attire, even for breakfast, and seemed to be preparing for meetings that did not exist on any official schedule.

Local newspapers from that period provide glimpses into the growing speculation about the governor’s unusual behavior. The Savannah Morning News published a brief item questioning why the governor had extended his planned 3-day visit indefinitely, while the Georgia Republican ran a more pointed editorial, wondering if the pressures of office had affected the governor’s judgment.

What these publications could not have known was that during those same weeks, Sarah had begun appearing in places where her presence violated every social convention of the time. Martha Cunningham, who managed the household staff for several prominent families, wrote to her sister in Augusta, describing an encounter that left her profoundly disturbed.

She had observed Sarah walking unescorted through Wright Square in the early morning hours, dressed in clothing that suggested wealth and status far beyond her station. More unsettling was Cunningham’s account of watching several white gentlemen approach Sarah as if seeking her counsel. Conversations that lasted for extended periods and concluded with the men handing her sealed envelopes.

The relationship between Governor Whitmore and Sarah evolved in ways that defied the social order everyone understood but no one discussed openly. Hotel records from the Marshall House, where the governor maintained a private suite for official business, show unusual patterns of meal deliveries and guest admissions during the period of his extended stay.

The hotel staff, according to testimony given years later during a legislative inquiry, reported that the governor frequently requested private dining arrangements for two despite having no scheduled meetings with any official visitors. Doctor Hartwell’s medical journal provides the most detailed contemporary account of the psychological transformation that seemed to overtake both the governor and Sarah during this period.

The physician noted that he was summoned to examine the governor for what Mrs. Peton described as episodes of profound melancholy alternating with periods of unusual animation. During his examination, Dr. Hartwell observed that the governor spoke repeatedly about having discovered truths that society cannot accommodate and appeared to be preparing for some form of dramatic action.

The governor’s official correspondence during this period preserved in the state archives reveals a man struggling with conflicts that he could not openly acknowledge. In a letter to his political mentor in Atlanta, Whitmore wrote, “The foundations upon which we have built our understanding of natural law require examination that may prove more unsettling than any of us anticipated.

I find myself questioning whether the order we defend serves justice or merely preserves comfort.” The letter was never sent, remaining instead among his private papers where it was discovered years later. Sarah’s influence appeared to extend beyond the governor to other prominent members of Savannah society.

Bank records uncovered during a federal investigation in 1869 revealed unusual financial transactions that suggested several wealthy families had made significant monetary transfers to accounts associated with the Peton estate. These payments, disguised as legitimate business transactions, followed a pattern that investigators later described as systematic compensation for unspecified services.

The social fabric of Savannah’s elite circles began showing signs of strain as rumors about the governor’s behavior spread throughout the community. Religious leaders privately expressed concern about what they perceived as a growing moral crisis among their most prominent parishioners. Reverend Whitfield’s sermon notes from that period, preserved in the church archives, reveal increasingly desperate attempts to address what he called the corruption of natural order through unlawful association.

By the summer of 1856, Governor Whitmore’s behavior had become impossible to ignore. He missed crucial legislative sessions, failed to attend mandatory social functions, and began issuing executive orders that his own staff described as inconsistent with established policy. The governor’s mansion staff reported that he frequently worked through the night, writing documents that he would burn before dawn, leaving only ashes in his fireplace as evidence of his nocturnal activities.

The crisis reached its climax during the harvest festival of 1856 when Governor Whitmore was scheduled to deliver the keynote address to Savannah’s assembled elite. Witnesses reported that the governor appeared on the platform in formal dress but seemed unable to begin his prepared remarks. Instead, according to multiple accounts, he stood silently for several minutes before announcing that he had discovered truths that required immediate action and departing the stage without further explanation.

That evening, according to testimony later given to a legislative committee, the governor was seen entering the Peton estate alone, carrying what witnesses described as a large leather portfolio. House staff reported unusual activity throughout the night with lamps burning in rooms that were normally unoccupied and sounds of conversation that continued until dawn.

By morning, both Governor Whitmore and Sarah had vanished without a trace. The investigation that followed revealed the extent to which Sarah had penetrated Savannah’s social structure. Hidden among her possessions, investigators found correspondence with prominent families throughout the South. Documents that suggested she had been conducting some form of intelligence gathering operation that reached into the highest levels of society.

More disturbing were the personal items discovered in her quarters, jewelry that belonged to prominent women who claimed never to have given it away, books that had disappeared from private libraries, and detailed maps of properties throughout Georgia and South Carolina. Cornelius Peton’s testimony to the investigating committee provided the most comprehensive account of Sarah’s presence in his household.

He claimed that she had arrived as a child with documentation that he had never questioned, and that her education had been overseen by tutors whose identities he could no longer recall. When pressed about the unusual freedoms she had been granted, Peon became evasive, stating only that certain arrangements had been made that required discretion.

The search for Governor Whitmore and Sarah extended throughout the southeast involving law enforcement agencies in three states. Railroad records showed no evidence that either had purchased tickets under their known names, while ship manifests from Savannah’s port revealed no passengers matching their descriptions.

Private investigators hired by the governor’s family reported discovering evidence that both had assumed false identities, but these leads invariably led to dead ends. Dr. Hartwell’s final journal entries about the case, written several months after the disappearance, reveal his growing conviction that Sarah’s influence had been far more extensive than anyone had realized.

The physician noted that several of his prominent patients began exhibiting symptoms of what he described as psychological distress following the sudden termination of a significant relationship. These individuals, all of whom had been frequent visitors to the Peton estate, appeared to be suffering from withdrawal symptoms typically associated with the loss of some form of regular stimulation.

The economic impact of the disappearance became apparent when several prominent families began experiencing financial difficulties that they could not adequately explain. Bank records revealed that the unusual monetary transfers to accounts associated with the Peton estate had continued until the very day of the disappearance, suggesting that Sarah had maintained financial relationships with multiple households simultaneously.

The amounts involved when calculated by investigators represented a significant drain on the accumulated wealth of Savannah’s elite families. Religious leaders struggled to address the spiritual crisis that seemed to engulf the community following the disappearance. Reverend Whitfield’s correspondence with church authorities in Atlanta reveals his belief that Sarah had somehow corrupted the moral foundation of his congregation.

His attempts to address this corruption through increased sermons about temptation and moral purity appeared to have little effect as attendance at evening services dropped dramatically in the months following her disappearance. The political ramifications of Governor Whitmore’s abandonment of office created a constitutional crisis that required intervention from the state legislature.

Lieutenant Governor Harrison Caldwell assumed executive authority but faced immediate challenges from political opponents who demanded a full investigation into Whitmore’s mental state and fitness for office. The inquiry that followed revealed the extent to which the governor’s personal crisis had compromised his official duties, leading to the passage of new legislation governing executive succession.

Private correspondence between prominent families discovered years later during estate settlements reveals the long-term psychological impact of Sarah’s presence in Savannah society. Men who had interacted with her regularly appeared to struggle with depression and anxiety for years following her disappearance while their wives reported dramatic changes in their husband’s behavior and temperament.

Several marriages ended in separation or divorce with court records citing fundamental incompatibility as the cause. The investigation into Sarah’s background eventually revealed that the documentation supporting her placement with the Peton family contained irregularities that suggested forgery.

Church records showed no evidence of the baptism that had supposedly occurred, while the witnesses listed in the placement documents either could not be located or claimed no memory of the events described. This discovery led investigators to conclude that Sarah’s entire identity may have been constructed for purposes that remained unclear.

By 1858, the official investigation into the disappearance was quietly closed due to lack of evidence. The final report, filed with minimal public attention, concluded that Governor Whitmore had suffered a mental breakdown and had fled the state with an accomplice whose motives remained unknown.

This official narrative satisfied few people who had witnessed the events firsthand, but served to protect the reputations of prominent families who had been involved in the investigation. The long-term consequences of the case continued to influence Savannah society for decades. Several prominent families sold their estates and relocated to other states, citing business opportunities that required their immediate attention.

The Peetton plantation was eventually abandoned with Cornelius Peton moving to Augusta where he lived in relative obscurity until his death in 1864. The property remained vacant until the 1870s when it was purchased by investors who demolished the original buildings. Local folklore began to develop around the abandoned Peton estate with residents reporting unusual phenomena that they attributed to the unresolved mysteries associated with the property.

These accounts collected by folklorists in the 1880s described sounds of conversation coming from the empty buildings, lights appearing in windows of structures that had no electricity, and the appearance of a woman matching Sarah’s description walking through the grounds at dawn and dusk. The social structure that had defined Savannah’s elite society never fully recovered from the crisis.

Families that had once socialized freely began maintaining careful distance from one another as if afraid that too much intimacy might lead to discoveries they were not prepared to confront. The elaborate dinner parties and social gatherings that had characterized the antibbellum period gave way to more formal carefully controlled interactions that minimized opportunities for unexpected revelations.

Doctor Hartwell’s medical practice evolved to focus increasingly on what he termed disorders of social anxiety as more prominent citizens sought treatment for symptoms that seem to have no physical cause. His case notes from this period preserved in the medical college of Georgia archives described patients who suffered from insomnia, loss of appetite, and persistent feelings of guilt or shame that they could not explain.

The physicians attempts to treat these conditions through conventional medicine proved largely unsuccessful. The educational system that had produced Sarah’s extraordinary level of learning became a subject of intense speculation among investigators. Despite extensive inquiries, no one could identify the tutors who had supposedly provided her education, nor could they locate any institutions that might have been responsible for her intellectual development.

This mystery led some investigators to conclude that her education had been conducted in secret, possibly as part of a larger plan that had been years in the making. Financial records from the period reveal that the economic disruption caused by Sarah’s activities extended beyond the immediate circle of prominent families.

Small businesses that had depended on the patronage of Savannah’s elite began experiencing difficulties as their wealthy customers reduced their social activities and curtailed their spending. The ripple effects of these changes contributed to a general economic decline that lasted well into the 1860s. The political career of Lieutenant Governor Caldwell, who had assumed executive authority following Whitmore’s disappearance, was permanently damaged by his association with the crisis.

Despite his efforts to distance himself from the investigation and maintain normal governmental operations, voters appeared to hold him responsible for the instability that had characterized the period. He lost his next election by a significant margin and retired from public life, citing health concerns that were never adequately explained.

Church records from the years following the disappearance show a significant increase in requests for private confession and spiritual counseling among Savannah’s prominent families. Reverend Whitfield’s appointment calendar preserved in the church archives reveals that he frequently conducted private meetings with parishioners who sought guidance for moral conflicts they could not discuss publicly.

The nature of these conflicts was never recorded, but the frequency of such meetings suggests widespread spiritual distress within the community. The legal system struggled to address questions raised by Sarah’s activities and subsequent disappearance. Property laws that had seemed clear and established were challenged when investigators discovered that several valuable items in her possession appeared to belong to families who claimed no knowledge of how she had acquired them.

The resolution of these ownership disputes required court proceedings that revealed uncomfortable truths about the extent of her access to prominent households. Marriage records from the period show an unusual pattern of delayed marriages and canceled engagements among young men from prominent families who had encountered Sarah during her years in Savannah.

Some of these men appeared unable to form lasting romantic attachments, while others married women who bore striking physical resemblances to her. This pattern persisted for several years after her disappearance, suggesting that her influence had created psychological obstacles that proved difficult to overcome. The architectural legacy of the Peton estate became a subject of study for investigators trying to understand how Sarah had maintained her secret activities.

Detailed examination of the buildings revealed hidden passages and concealed rooms that had not appeared in the original construction plans. These discoveries suggested that the estate had been modified to facilitate private meetings and secret communications, possibly over a period of many years. Transportation records from the period reveal unusual patterns of travel between Savannah and other southern cities that coincided with Sarah’s presence in the community.

Stage coach companies reported an increase in passengers traveling under assumed names. While ship captains noted unusual requests for private passage that avoided normal passenger manifests. These patterns suggested that Sarah’s activities were part of a larger network that extended throughout the region. The preservation of documents related to the case became problematic when several key pieces of evidence disappeared from official files.

Court records showed that important testimony had been removed from transcripts while investigative reports were found to have crucial pages missing. These losses appeared to be deliberate, suggesting that someone with access to official files had systematically removed information that might have revealed the true scope of Sarah’s influence.

By 1860, most direct witnesses to the events had either died or moved away from Savannah, leaving behind only fragmentaryary accounts that raised more questions than they answered. The few individuals who remained and were willing to discuss their experiences spoke of feeling as though they had been participants in events that defied rational explanation.

Their accounts collected by a journalist for the Atlanta Constitution described a sense of having been caught up in circumstances beyond their understanding or control. The educational institutions that had served Savannah’s elite families began implementing new policies designed to prevent the type of secret education that Sarah had apparently received.

Private tutors were required to provide detailed records of their curriculum and teaching methods, while families were encouraged to maintain closer supervision of their household staff. These measures reflected a communitywide anxiety about the possibility that similar situations might develop in the future. Economic analysis of the period reveals that the financial disruption caused by Sarah’s activities had lasting effects on Savannah’s position as a regional commercial center.

The loss of confidence among the business community combined with the economic instability experienced by prominent families contributed to a gradual decline in the city’s influence relative to other southern commercial centers. This decline continued throughout the 1860s and was accelerated by the disruptions of the Civil War.

The medical community struggled to understand the psychological symptoms that seemed to persist among individuals who had been closely associated with Sarah. Dr. Hartwell’s correspondence with colleagues in other cities reveals his frustration with conventional treatments that proved ineffective for conditions that appeared to have no physical basis.

His attempts to develop new therapeutic approaches were hampered by his patients reluctance to discuss the specifics of their experiences. Social customs that had governed interactions between different social classes underwent significant changes following the crisis. The informal arrangements that had previously allowed for flexible relationships between household staff and their employers were replaced by rigid protocols designed to prevent the development of inappropriate intimacies. These changes reflected a

communitywide recognition that the traditional social structure contained vulnerabilities that could be exploited by individuals with sufficient intelligence and determination. The theological implications of the case created lasting divisions within Savannah’s religious community. Some ministers interpreted the events as evidence of fundamental moral corruption that required dramatic spiritual renewal, while others argued that the crisis had been caused by external forces that did not reflect on the spiritual condition of the community.

These disagreements led to permanent schisms within several congregations and contributed to a general decline in religious observance among prominent families. Legal scholars who studied the case in later years identified it as a turning point in the development of laws governing personal relationships and property rights.

The ambiguities revealed by Sarah’s activities led to new legislation designed to clarify the legal status of individuals whose social position was unclear or disputed. These laws had farreaching implications for the treatment of enslaved individuals and free people of color throughout the South.

The architectural legacy of the case influenced building practices throughout the region as wealthy families sought to prevent the type of hidden modifications that had characterized the Peton estate. New construction incorporated security features designed to ensure that all rooms and passages were visible and accessible to property owners.

Existing buildings were extensively renovated to eliminate potential hiding places and secret meeting areas. The investigation’s failure to locate Governor Whitmore and Sarah created lasting questions about the effectiveness of law enforcement agencies in cases involving prominent citizens. The inability of multiple police departments and private investigators to discover any trace of two such distinctive individuals suggested either extraordinary planning or assistance from individuals with significant resources and influence.

This mystery contributed to public skepticism about official institutions that persisted for decades. The impact on Savannah’s cultural life was profound and lasting as the social gatherings and intellectual salons that had characterized the antibbellum period never fully recovered from the crisis. The fear that intimate social interactions might lead to dangerous revelations or inappropriate relationships caused families to retreat into formal carefully controlled social patterns that minimized opportunities

for meaningful connection. This cultural shift had implications that extended far beyond the immediate participants in the events. By 1865, the few remaining documents that reference the case had been quietly removed from public access and placed in restricted archives. The official explanation cited concerns about public order and the need to protect the privacy of surviving family members.

This action effectively ended public discussion of the events and created a situation where the case became known only through fragmentaryary oral accounts that grew increasingly unreliable over time. The long-term psychological effects on the Savannah community included a persistent anxiety about the possibility that other individuals might have been conducting similar secret activities.

Families began investigating the backgrounds of their household staff more thoroughly while social interactions were subjected to new levels of scrutiny and suspicion. This atmosphere of mistrust contributed to the breakdown of the informal social networks that had previously bound the community together.

Research conducted in the 1880s by historians interested in antibbellum social structures revealed that the case had been part of a broader pattern of social disruption that affected multiple southern cities during the 1850s. Similar disappearances and mysterious relationships had been reported in Charleston, New Orleans, and Richmond, suggesting that Sarah’s activities in Savannah may have been connected to a larger network of individuals with similar objectives and methods.

The economic records that survived the various attempts to suppress information about the case revealed that the financial transactions associated with Sarah’s activities had involved amounts that far exceeded what investigators had initially estimated. When calculated in contemporary terms, the money that had been transferred to accounts associated with her activities represented a significant portion of the accumulated wealth of Savannah’s elite families.

The discovery of this information helped explain the extraordinary efforts that had been made to suppress public discussion of the case. The educational implications of the case led to fundamental changes in the way wealthy southern families approached the intellectual development of their household staff.

The recognition that enslaved individuals could achieve levels of education that rivaled or exceeded those of their supposed superiors created anxiety about the stability of the social order that had profound political implications. These concerns contributed to the development of new laws restricting access to education for enslaved individuals and free people of color.

The architectural investigation of the Peton estate revealed construction techniques and hidden features that suggested the involvement of skilled craftsmen who had received specific instructions about creating concealed spaces. The identity of these craftsmen was never established, but the sophistication of the modifications suggested a level of planning and coordination that extended well beyond what a single individual could have accomplished.

This discovery raised questions about how many people had been aware of or involved in Sarah’s activities. The social networks that had connected Savannah’s elite families to similar communities throughout the South underwent significant changes following the crisis. Correspondence that had once flowed freely between prominent families was reduced to formal business communications, while the informal visiting patterns that had characterized antibbellum social life were replaced by carefully planned and supervised

interactions. These changes reflected a widespread loss of confidence in the ability to distinguish between legitimate social relationships and potentially dangerous associations. The religious revival that swept through Savannah in the years following the disappearance reflected the community’s attempt to address spiritual concerns that conventional religious practices had seemed unable to resolve.

New churches were established with stricter moral codes and more intensive supervision of congregation members. While existing churches implemented new policies designed to prevent the development of inappropriate relationships between clergy and parishioners. These changes represented a communitywide recognition that traditional religious institutions had been inadequate to prevent or address the spiritual crisis that had occurred.

The investigation’s focus on financial transactions revealed a complex network of payments and transfers that suggested Sarah had been receiving regular compensation from multiple sources for services that were never clearly identified. The amounts involved and the regularity of the payments indicated that these were not casual gifts or temporary arrangements, but rather systematic compensation for ongoing activities that had significant value to the individuals making the payments.

The nature of these services remained a subject of speculation among investigators, but the evidence suggested that they involved access to information or influence that was not otherwise available. The medical records associated with the case revealed that several prominent individuals had sought treatment for conditions that appeared to be related to the sudden termination of their relationships with Sarah. Dr.

Hartwell’s notes described symptoms that included severe depression, anxiety, and what he termed a persistent sense of loss that appeared to be unrelated to any obvious external cause. These symptoms proved difficult to treat with conventional medicine and persisted for extended periods in several cases, suggesting that the relationships had involved psychological dependencies that were not immediately apparent to outside observers.

The legal precedents established by the case had lasting implications for the development of property law and personal rights throughout the south. The questions raised about ownership of items found in Sarah’s possession led to new regulations governing the transfer and possession of valuable property. While the ambiguities surrounding her legal status contributed to the development of more precise definitions of personal freedom and social position.

These legal changes had farreaching consequences that extended well beyond the immediate circumstances of the case. The cultural impact of the disappearance included changes in the way southern society approached questions of beauty, intelligence, and social position. The recognition that Sarah had used her appearance and intellect to gain access to levels of society that should have been forbidden to someone of her supposed status created anxiety about the reliability of traditional social markers. This anxiety contributed to the

development of new social protocols designed to verify and maintain appropriate social boundaries. The investigative techniques that proved ineffective in solving the case led to the development of new methods for tracking individuals and monitoring social relationships. Law enforcement agencies throughout the South began maintaining more detailed records of population movements and implementing new procedures for verifying personal identities.

Private investigation services expanded their operations to include surveillance of social interactions and background investigations of individuals in sensitive positions. The architectural modifications discovered at the Peton estate became the subject of detailed study as investigators attempted to understand how such extensive secret construction could have been completed without attracting attention from neighbors or local authorities.

The techniques used suggested knowledge of advanced construction methods and access to specialized materials that would not have been readily available to most individuals. This discovery led to new regulations governing building modifications and increased oversight of construction activities in prominent neighborhoods.

The social psychology of the case continued to intrigue researchers who studied the ways in which a single individual could disrupt established social patterns through the systematic cultivation of personal relationships. Sarah’s apparent ability to gain the confidence and dependency of multiple prominent individuals simultaneously suggested skills and knowledge that exceeded what would have been expected from someone of her background and social position.

The methods she used to achieve this influence remained largely mysterious, but the evidence suggested a sophisticated understanding of human psychology and social dynamics. The economic analysis of the case revealed patterns of financial manipulation that had gone undetected for several years, suggesting that Sarah had possessed knowledge of business and financial matters that far exceeded what would have been expected from someone in her position.

The discovery of these patterns led to new auditing procedures and increased oversight of financial transactions involving prominent families. The recognition that significant amounts of money could be diverted through seemingly legitimate transactions created anxiety about the security of traditional financial arrangements. In 1868, a final attempt was made to locate Governor Whitmore and Sarah when reports surfaced of individuals matching their descriptions living quietly in a small town in western Virginia.

Investigators who traveled to examine these reports found that the individuals in question had indeed lived in the area for several years, but had departed suddenly several days before the investigator’s arrival. Local residents provided descriptions that were consistent with the missing persons, but were unable to provide information about their current whereabouts or planned destination.

The failure of this final investigation led to the official closure of the case and the sealing of all related documents in state archives where they remained until their accidental discovery during a renovation project in 1958. The researcher who found these documents, Professor Margaret Thompson of the University of Georgia, noted in her preliminary report that the case represented one of the most thoroughly documented examples of social disruption in antibbellum southern society, but her planned comprehensive study was never completed due to her sudden death in

-

The social transformation that Savannah underwent following the crisis established patterns that influenced the city’s development for decades. The retreat from informal social relationships and the emphasis on rigid social protocols created a community atmosphere that many observers described as cold and unwelcoming compared to the warmth and spontaneity that had characterized antibbellum social life.

This change contributed to the city’s declining influence as a cultural center and affected its ability to attract new residents and businesses. The religious and moral questions raised by the case continued to influence southern theological thought throughout the 19th century. The recognition that traditional moral teachings had been insufficient to prevent the spiritual crisis that had occurred led to the development of new approaches to religious education and moral guidance.

These changes had lasting implications for the role of religious institutions in southern society and contributed to the development of more rigid moral codes that characterized post civil war religious practices. The investigation’s documentation of the complex financial relationships that Sarah had maintained with prominent families provided valuable insights into the economic structure of antibbellum southern society.

The evidence revealed patterns of wealth concentration and financial dependency that had previously been hidden from public view, contributing to a better understanding of the economic forces that shaped social relationships in the period before the Civil War. The case’s impact on law enforcement practices included the development of new investigative techniques and the establishment of better coordination between different police agencies.

The failure to locate Governor Whitmore and Sarah, despite extensive efforts involving multiple jurisdictions, led to the creation of new procedures for multi-state investigations and improved methods for sharing information between different law enforcement agencies. The psychological studies that emerged from analysis of the case contributed to early developments in the field of abnormal psychology and provided insights into the ways in which individuals could develop dependencies on relationships that appeared normal to

outside observers. The symptoms exhibited by individuals who had been closely associated with Sarah became the subject of medical research that contributed to better understanding of psychological conditions that had no apparent physical cause. The social protocols that developed in response to the crisis became models for similar communities throughout the south that sought to prevent comparable disruptions to their social order.

The emphasis on formal relationships, careful supervision of household staff, and systematic verification of personal backgrounds became standard practices among wealthy southern families and contributed to the development of a more rigid and hierarchical social structure. The architectural innovations that were developed to prevent the type of secret modifications found at the Peetton estate influenced building practices throughout the region and contributed to the development of new construction techniques that emphasized security and

oversight. The recognition that traditional building methods could be exploited to create hidden spaces led to the adoption of new design principles that became standard features of prominent southern homes. The long-term consequences of the case included changes in educational policies that restricted access to advanced learning for enslaved individuals and free people of color throughout the South.

The recognition that Sarah’s extraordinary education had enabled her to disrupt established social patterns led to new laws and social practices designed to prevent similar situations from developing in the future. Years have passed since these events shook the foundations of Savannah society, but the questions they raised about the nature of social order, personal relationships, and hidden influences continue to resonate.

The official records remain sealed. The witnesses have long since passed away. And the truth about what really transpired during those crucial months may never be fully known. What remains is a haunting reminder that beneath the surface of even the most carefully constructed social arrangements. There may exist forces and individuals whose true nature and objectives remain hidden until the moment they choose to reveal themselves.

The empty lot where the Peton estate once stood serves as a silent monument to events that challenged everything a community believed about itself. On certain mornings, when the fog rolls in from the Savannah River and the Spanish moss hangs heavy in the still air, residents passing by have reported hearing what sounds like distant conversation, as if the secrets that were buried with the demolished buildings continue to echo through the years.

And perhaps in the end that is the most disturbing truth of all that some mysteries are meant to remain unsolved. Some questions are too dangerous to answer and some secrets are powerful enough to reshape the very foundations of the world we think we understand. The final chapter of this investigation came to light in 1962 when workmen renovating the basement of the Savannah Public Library discovered a metal box hidden behind a false wall.

Inside, wrapped in oiled cloth, were documents that provided the last known evidence of Sarah’s presence in the city. Among these papers was a letter written in Governor Whitmore’s distinctive handwriting addressed to no one in particular, but dated the night before their disappearance. The letter, now preserved in the restricted archives of the Georgia Historical Society, contained what appeared to be a confession of sorts.

Whitmore wrote, “I have discovered that the order we defend exists only through the systematic suppression of truths that would destroy the very foundation of our society. The woman known as Sarah has shown me documents, correspondence, and evidence of arrangements that reach into every prominent household in this region. We are not the masters we believe ourselves to be.

” J the governor’s final words proved prophetic. Among the other documents in the hidden box were detailed records of financial transactions, copies of private correspondents between prominent families, and what appeared to be a comprehensive list of individuals throughout the South who had been involved in similar arrangements. The scope of the network, these documents revealed, suggested that Sarah’s activities in Savannah were merely one component of a much larger operation that had been conducted across multiple states for decades. Dr. Hartwell’s final

medical journal entry, also found in the box, provided the most chilling conclusion to the mystery. Written just days before the disappearance, the physician noted, “I have come to understand that Sarah was never truly enslaved in the conventional sense. The documents, the education, the extraordinary access she maintained to prominent households all point to a truth that our society is not prepared to confront.

She was conducting an investigation of us.” The implications of this revelation reverberated through the few scholars who were granted access to the sealed documents. The evidence suggested that for years, possibly decades, individuals like Sarah had been systematically documenting the private lives, financial arrangements, and hidden relationships of the South’s most prominent families.

The purpose of this documentation remained unclear, but the thoroughess and precision of the records indicated an operation of extraordinary scope and sophistication. The last confirmed sighting of Governor Whitmore and Sarah came in 1859 when a riverboat captain reported transporting two passengers matching their descriptions across the Mississippi River near New Orleans.

The captain noted that they traveled with minimal luggage, but carried a large trunk that they guarded carefully. When questioned about their destination, they provided conflicting answers that suggested they were deliberately obscuring their plans. The trunk, according to the captain’s later testimony, appeared to contain documents or papers, as he could hear the rustling of papers whenever the boat encountered rough water.

The passengers paid their fair with gold coins that bore unusual markings, suggesting they had access to currency that was not in general circulation. They disembarked at a small landing north of New Orleans and disappeared into the Louisiana wilderness. The investigation into the broader network that Sarah represented was quietly discontinued in 1863 as the Civil War consumed the attention and resources of law enforcement agencies throughout the South.

The documents that had been discovered were classified and removed from public access, while the few individuals who had been aware of the investigation were reassigned to other duties or encouraged to relocate to different regions. In the years that followed, several other prominent southern families experienced similar crises involving trusted household staff who disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

taking with them valuable documents and leaving behind evidence of activities that defied conventional understanding. These incidents were handled discreetly by local authorities and rarely received public attention, but they suggested that the network Sarah had been part of continued to operate throughout the region.

The social transformation that Savannah underwent in the wake of these events became a model for other southern communities that sought to protect themselves from similar disruptions. The emphasis on formal relationships, careful documentation of household activities, and systematic verification of personal backgrounds became standard practices that influenced southern social customs well into the 20th century.

The few families that remained in Savannah after the crisis developed a culture of silence that persisted for generations. Children were taught never to discuss certain topics, while family histories were carefully edited to exclude references to events that might raise uncomfortable questions. This culture of deliberate forgetting became so deeply ingrained that by the early 1900s most residents had no knowledge of the events that had shaped their community’s cautious and reserved character. The economic impact of the

crisis contributed to Savannah’s decline as a major southern port as the loss of confidence among the business community made it difficult to attract new investment and maintain existing commercial relationships. The city that had once been known for its vibrant social life and cultural sophistication became characterized by an atmosphere of caution and suspicion that discouraged the kind of open interaction necessary for commercial success.

The religious institutions that had struggled to address the spiritual crisis left by Sarah’s influence eventually adopted more conservative theological positions that emphasized strict moral boundaries and careful supervision of congregation members. The informal spiritual counseling that had characterized antibbellum religious practice was replaced by formal confession procedures and systematic monitoring of personal behavior.

The architectural legacy of the case influenced building practices throughout the south as wealthy families incorporated security features designed to prevent the type of secret modifications that had been discovered at the Peton estate. Hidden passages and concealed rooms became virtually unknown in prominent southern homes, while existing buildings were extensively renovated to eliminate potential hiding places.

The legal precedents established by the investigation contributed to the development of new laws governing personal relationships and property rights that had lasting implications for southern society. The recognition that traditional legal categories were inadequate to address the complexities revealed by Sarah’s activities led to more detailed legislation governing the rights and responsibilities of individuals in various social positions.

The medical understanding of the psychological conditions that had affected individuals closely associated with Sarah contributed to early developments in the field of psychiatry. and provided insights into the nature of psychological dependency that influenced medical practice for decades. Doctor Hartwell’s detailed case notes became the subject of study by physicians throughout the region who encountered similar symptoms in their own patients.

The investigative techniques that proved inadequate to solve the case led to the development of new methods for tracking individuals and monitoring social relationships that became standard practices for law enforcement agencies throughout the South. The recognition that traditional investigative approaches were insufficient to address cases involving sophisticated planning and coordination led to the adoption of more systematic and comprehensive investigative procedures.

Today, more than a century and a half after these events occurred, the truth about Sarah and Governor Whitmore remains as elusive as ever. The documents that might have provided definitive answers have been lost, destroyed, or sealed in archives that remain inaccessible to researchers. The few contemporary accounts that survive raise more questions than they answer, while the official records that were created during the investigation appear to have been deliberately obscured or edited to remove crucial information.

What cannot be disputed is the profound impact that these events had on savannah society and the lasting changes they brought to southern social customs and institutions. The recognition that beneath the surface of even the most carefully constructed social arrangements, there may exist forces and individuals whose true nature and objectives remain hidden, has left a permanent mark on the collective consciousness of a community that learned too late that the world they thought they understood was far more complex and dangerous than they had ever

imagined. The empty lot where the Peton estate once stood remains undeveloped to this day despite numerous attempts by developers to build on the valuable riverfront property. Local residents attribute this to practical concerns about soil stability and drainage issues, but older families quietly acknowledge that some places are better left undisturbed.

And sometimes on foggy mornings when the Spanish moss hangs heavy in the still air, visitors to Savannah report hearing what sounds like distant conversation carried on the wind from the direction of the abandoned lot. Whether these sounds are merely the echo of traffic from nearby streets or something more mysterious remains a matter of individual interpretation.

But for those who know the history, who understand what once transpired in the grand mansion that overlooked the Savannah River