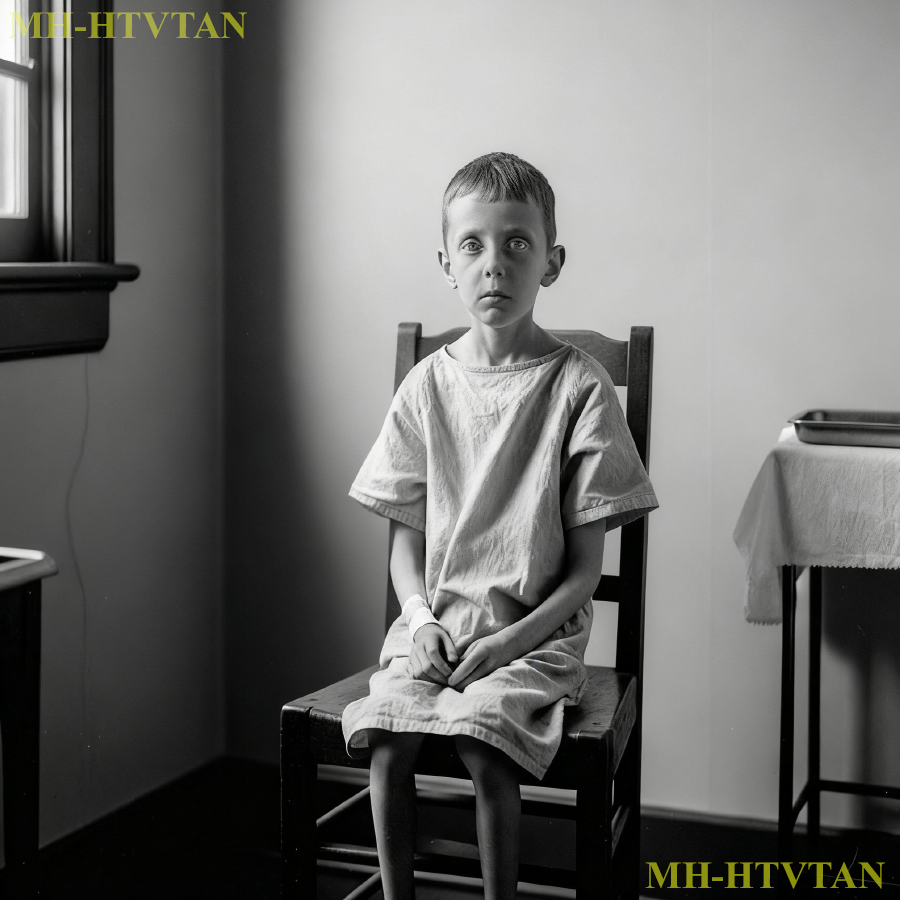

In the autumn of 1847, in a small hospital on the outskirts of Boston, Massachusetts, something occurred that would challenge everything the medical community thought they understood about the boundary between life and death. A 7-year-old boy named Daniel Frost was declared clinically dead by three different physicians.

His heart had stopped, his breathing had ceased, and his body had grown cold to the touch. But for the next 43 minutes, while his body lay lifeless on the examination table, Daniel Frost continued to speak. This is the story documented in the private medical journals of Dr. Samuel Morrison, chief physician at St.

Margaret’s Hospital and corroborated by the sworn testimonies of 12 witnesses, including two reverends, a magistrate, and seven medical professionals. A story about a child who may have discovered a way to exist in two states of reality simultaneously. To understand the magnitude of what happened in that small hospital room in 1847, we must first immerse ourselves in the medical landscape of mid9th century America.

This was an era before the discovery of germ theory, before anesthesia became commonplace, and decades before anyone would understand the electrical nature of the human heart. Boston, where our story unfolds, was at the forefront of American medicine. The city housed the Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811 and Harvard Medical School, which was producing some of the nation’s most innovative physicians.

But even with this concentration of medical knowledge, doctors of the era had only the most rudimentary understanding of death itself. The stethoscope had been invented just 30 years earlier. The concept of resuscitation was virtually unknown. Once a heart stopped beating, death was considered absolute and irreversible.

Saint Margaret’s Hospital, where Daniel Frost was admitted, was a modest institution serving the working-class neighborhoods west of the city center. With only 40 beds and a staff of six physicians, it was typical of the small community hospitals that served America’s growing urban populations. The autumn of 1847 had been particularly harsh.

An outbreak of typhoid fever had swept through the poorer districts, overwhelming the limited medical facilities. It was during this crisis that Daniel Frost first came to the attention of the medical community. On October 12th, 1847, Daniel Frost was brought to St. Margaret’s Hospital by his mother, Catherine Frost, a widow who worked as a seamstress.

In her initial statement to Dr. Morrison preserved in the hospital’s admission records. She described symptoms that had begun 3 days earlier. “Daniel had been complaining of terrible headaches,” she wrote in her testimony, later recorded by the hospital cler. “But what frightened me most was not the pain, but the strange things he began to say during his episodes.

” According to Catherine’s account, Daniel had begun experiencing what she described as fits of absence. Periods where he would suddenly stop whatever he was doing. His eyes would glaze over and he would begin speaking in a voice that she insisted was his, but somehow wasn’t. It was as if my Daniel was reading words from a book I couldn’t see, she testified.

He would describe places he’d never been, speak of events that hadn’t happened yet, and name people who didn’t exist. But the most unsettling part was how he spoke with perfect clarity and detail as if he were actually seeing these impossible things. Dr. Morrison’s initial examination of Daniel Frost, documented in meticulous detail in his medical journal, revealed a boy in apparent good health, aside from an elevated temperature and signs of fatigue.

But what caught Morrison’s attention were the episodes Catherine had described. I had the opportunity to observe one of these absences during my examination, Morrison wrote. The boy was answering my questions normally when, without warning, his eyes took on a distant quality. His voice, which had been that of a typical 7-year-old child, suddenly became clearer, more articulate, and strangely mature.

Morrison documented what Daniel said during this episode. The boy began describing a room in the hospital, the surgical theater on the third floor, which he had never visited. He described its dimensions, the placement of windows, even the crack in the northwest corner of the ceiling. I later verified every detail.

He was perfectly accurate. But what truly alarmed Morrison was what happened next. Daniel, still in his translike state, turned to the doctor and said something that Morrison would never forget. Dr. Morrison, in 3 days I will die in your operating room, but I won’t leave. I’ll still be here trying to tell you something important.

The prediction troubled Morrison deeply. As a man of science, he rejected superstition, but as a physician, he had learned to trust his instincts when something felt wrong. He admitted Daniel for observation, placing him in a private room where he could be monitored continuously. Over the next 3 days, Daniel’s condition deteriorated rapidly.

The headaches intensified, and the episodes of absence became more frequent and prolonged. During each episode, Daniel would speak with that same unnerving clarity, describing impossible things. He spoke of surgeries that hadn’t been performed yet, naming patients who would arrive at the hospital in the coming weeks.

He described medical procedures that wouldn’t be invented for decades. He talked about a world of breath and heartbeat that existed parallel to the physical world, a realm he claimed he could see during his episodes. Dr. Morrison brought in colleagues to observe. Dr. William Hartwell, a specialist in nervous disorders from Massachusetts General Hospital, examined Daniel on October 14th.

His notes, preserved in the archives of the Boston Medical Society, corroborate Morrison’s observations. The child displays symptoms unlike any I have encountered in my 20 years of practice, Hartwell wrote. During his episodes, his pupils dilate to an extraordinary degree. Yet, he shows no signs of epilepsy or other neurological conditions known to cause seizures.

Most remarkably, his pulse becomes irregular during these states, not faster or slower, but following patterns that seem almost mathematical in their complexity. On the morning of October 15th, 1847, exactly 3 days after Daniel’s prediction, the boy’s condition took a critical turn. His temperature spiked dramatically, and he began experiencing violent convulsions.

Dr. Morrison made the decision to perform an emergency procedure to relieve pressure on the brain, a desperate measure for a condition he didn’t fully understand. The surgery was scheduled for 2:00 that afternoon. By 1:30, Daniel had been prepared and moved to the operating theater, the same room he had described with perfect accuracy 3 days earlier.

What happened in that operating theater over the next hour would be documented by 12 separate witnesses, each providing detailed accounts that remarkably aligned in almost every particular. Dr. Morrison began the procedure at precisely 2:04 p.m. as noted in the surgical log. Assisting him were Dr. Hartwell, two surgical nurses, and a medical student from Harvard.

In the observation gallery above, seven other physicians had gathered to watch the unusual case. Also present at Katherine Frost’s request were Reverend Joseph Whitmore of the Second Congregational Church and Father Patrick Donnelly of St. Mary’s Catholic Church. The presence of both Protestant and Catholic clergy was unusual, but Catherine, desperate to help her son, had sought spiritual support from both traditions.

Magistrate Harold Peton, a friend of Dr. Morrison, was also present, having heard about the strange case and come to observe out of personal interest. The procedure began normally. Daniel had been sedated with Lordum, a common practice of the era. Dr. Morrison made his initial incision and for the first few minutes everything proceeded as expected. Then at 2:17 p.m.

Morrison noted the exact time. Daniel’s heart stopped beating. Duck Hartwell, who was monitoring the boy’s vital signs, later testified, “I had my fingers on his radial pulse when it simply ceased. Not a flutter, not a weak beat. It stopped completely, as if someone had turned off a mechanism.

” Morrison immediately ceased the surgical procedure. For the next several minutes, he and Hartwell attempted various methods to revive Daniel, applying pressure to the chest, administering stimulants, even attempting to manually compress the heart through the open incision. Nothing worked. At 2:23 p.m.

, after consulting with Hartwell, Morrison officially declared Daniel Frost dead. It was at this moment that something impossible occurred. From Daniel’s throat came a sound, not a gasp or a death rattle, but a clear, distinct word. Doctor. Every person in that operating theater heard it. Morrison’s hand, which had been about to cover Daniel’s face with a cloth, froze in midair.

Morrison, Daniel’s voice continued, still clear despite the absence of breath or heartbeat. Listen carefully. I’m speaking from the place between Dr. Morrison’s journal entry from that day, written while the events were still fresh in his memory, captures his shock. I have been a physician for 18 years. I know what death looks like, feels like, sounds like. Daniel Frost was dead.

His heart had stopped. His breathing had ceased. His skin was growing cold. And yet, he was speaking with perfect clarity. Dr. Hartwell immediately checked Daniel’s vital signs again. His testimony to the medical board of Massachusetts given 3 weeks later was unequivocal. There was no pulse, no breath.

I placed my ear directly on his chest. The heart was silent. I held a mirror to his mouth. There was no condensation. By every measure known to medical science, the child was deceased. Yet Daniel continued to speak. “I can see both places now,” Daniel<unk>’s voice said, emanating from his motionless body. The world where hearts beat and lungs breathe and the world beyond it.

I’m standing between them and I can see things that haven’t happened yet. Reverend Whitmore, watching from the gallery, later described his reaction in a letter to his bishop. My first thought was that I was witnessing a miracle or perhaps a deception. But as Daniel continued to speak, describing events and revealing knowledge he could not possibly possess, I became convinced I was observing something that transcended both miracle and fraud, something entirely outside our frameworks of understanding.

For the next 43 minutes, Daniel Frost’s dead body continued to speak, and what he said during those minutes would haunt everyone present for the rest of their lives. Daniel described in precise detail events that would occur in the hospital over the coming months. He named patients who would arrive, described their ailments, and explained how they should be treated, often with methods that wouldn’t be standard practice for years.

He spoke of Anna Kowalsski, who would be admitted on November 2nd with poor paral fever, and explained a specific treatment protocol involving cleanliness and isolation that would save her life. Dr. Morrison, though skeptical, documented everything. He described William Mercer, who would arrive on November 18th after a factory accident and detailed a surgical technique for setting compound fractures that Dr.

Morrison had never heard of, but which when later attempted proved remarkably effective. But Daniel didn’t only speak of hospital matters. He made predictions about the world beyond the hospital walls. There will be a fire on Hanover Street on November 3rd, he said, his voice still clear despite his body’s complete lack of vital signs.

Three families will lose their homes. Tell them to check their stove pipes. The fire starts in the building marked with the blue door. He spoke of a merchant ship called the Providence that would arrive in Boston Harbor on November 10th carrying passengers sick with cholera. They must be quarantined immediately, Daniel’s voice insisted.

The disease is in the water they drank. The ship’s water barrels were contaminated in New York. Most disturbing of all, Daniel spoke about himself. “My body is dying,” he explained, his voice maintaining that same unnerving clarity. “But the part of me that thinks, that knows, that speaks, it’s finding a different way to exist.

I can feel myself spreading out, becoming something less solid, but more aware. Soon I won’t be able to speak like this anymore. The connection is getting harder to maintain. Magistrate Peetton, who had been taking detailed notes throughout, later testified, “I am trained to detect deception.

I have questioned hundreds of witnesses in my career. But as I listened to that child speak while his body showed no signs of life, I became convinced of two things. First, that what I was witnessing was impossible according to all natural law. and second that it was nevertheless genuinely happening.

At 3 RPM, Daniel’s voice began to change. The clarity that had been so remarkable started to waver. Words became slurred, then fragmented. “I’m losing the connection,” Daniel said, his voice now sounding distant, as if coming from the end of a long tunnel. “One more thing I important I must tell you.

” Everyone in the room leaned forward, straining to hear the boundary between life and death. It’s not a wall. It’s a membrane, thin, permeable. Consciousness doesn’t need a beating heart. And to exist, it needs something else. Something we don’t have words for. Dr. Morrison, in the coming years, you will see many die. Remember, they’re not gone, just changed, existing differently.

If you listen carefully, you can sometimes hear them, trying to communicate from the space between. At 3:07 p.m., Daniel’s voice ceased. This time, there was no possibility of revival, no ambiguity about what had occurred. The speaking had stopped as definitively as it had begun. Dr. Morrison waited another hour before officially declaring the death for the second time and authorizing the removal of Daniel’s body.

The immediate aftermath of Daniel Frost’s death was marked by intense debate and controversy within Boston’s medical and religious communities. Dr. Morrison, true to his scientific principles, documented everything in meticulous detail and submitted a report to the Boston Medical Society. The society’s response was swift and unequivocal.

They rejected Morrison’s account as impossible, unscientific, and likely the result of collective delusion brought on by the stress of an unsuccessful surgery. But Morrison had anticipated skepticism. He had collected written testimonies from all 12 witnesses, each describing the same events from their different perspectives.

He had Magistrate Peton’s official notorized statement. He had letters from both Reverend Whitmore and Father Donnelly, each swearing under their religious vows that the account was accurate. The controversy split Boston’s medical establishment. Some physicians defended Morrison, arguing that science required investigating unexplained phenomena, not dismissing them.

Others saw the case as an embarrassment to the profession, a regression to the dark ages of superstition and mysticism. Dr. William Hartwell, whose reputation was impeccable, faced particular pressure to recant his testimony. In a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine, published in December 1847, he refused. I cannot and will not deny what I witnessed with my own eyes and ears.

Hartwell wrote, “If accepting this testimony damages my reputation, so be it. I am first and foremost a physician, and physicians must face reality, even when reality proves more strange than we believed possible.” But what ultimately silenced many skeptics was what happened in the weeks following Daniel’s death.

Every prediction he had made during those 43 minutes came true. Anna Kowalsski was admitted to St. Margaret’s on November 2nd exactly as Daniel had predicted with poor paral fever. Dr. Morrison remembering the boy’s words implemented the cleanliness protocol Daniel had described. Against all odds, Anna survived.

One of the first documented cases of poor parole fever being successfully treated before the acceptance of germ theory. William Mercer arrived on November 18th with the compound fracture. Daniel had described. Morrison used the surgical technique the boy had detailed. The operation was successful and Mercer recovered with full use of his limb.

Unusual for such injuries at the time. The fire on Hanover Street occurred on November 3rd, starting in the building with the blue door, exactly as Daniel had said. Three families lost their homes, but because Morrison had warned the authorities who increased patrols in that area, everyone escaped safely.

The merchant ship Providence arrived in Boston Harbor on November 10th. Remembering Daniel’s warning, harbor officials imposed an immediate quarantine. Seven passengers were found to be infected with cholera. The quick action prevented an outbreak that could have killed hundreds. Each fulfilled prediction added weight to the testimony.

Even those who had dismissed Morrison’s account as delusion began to question their certainty. In January 1848, the Boston Medical Society held a closed door meeting to discuss the case. According to minutes that were kept sealed for 70 years and only made public in 1918, the society reached a troubling conclusion.

While we cannot accept the possibility that the deceased child spoke without vital signs, the official statement read, “We must acknowledge that something extraordinary occurred in that operating theater. Whether it was a case of death being incorrectly diagnosed, some unknown medical phenomenon, or something that falls outside the current boundaries of medical understanding, we cannot say with certainty.

The statement continued with a recommendation that proved prophetic. We advise that this case be studied further, but that public discussion be discouraged until such time as a scientific framework exists to properly analyze what was witnessed. In other words, the case was too dangerous to dismiss, but too impossible to accept, so it was quietly buried in the archives. Dr.

Samuel Morrison never fully recovered from the experience. His medical journals, which he kept until his death in 1871, contain frequent references to Daniel Frost. Morrison became obsessed with the boundary between life and death, conducting research into consciousness, and attempting to develop methods for communicating with dying patients.

In an entry from 1852, Morrison wrote, “I have attended to more than 300 deaths since Daniel Frost, and in several cases, perhaps a dozen, I have experienced something I cannot explain. A sensation of presence, a feeling that the deceased is trying to communicate something. Are these merely my imagination fueled by my experience with Daniel? Or did that remarkable boy show me something real about the nature of consciousness that I am only beginning to understand? Morrison’s later journals describe experiments he conducted,

always in private, attempting to document any signs of consciousness or communication during the dying process. He developed a set of questions he would ask dying patients, requesting that they attempt to communicate specific information after death if they were able. Three times he wrote in 1858, “I have received information that seems to have come from deceased patients delivered through the words of other dying patients who had no possible way of knowing these details.

Is this evidence of something Daniel tried to tell us? That consciousness doesn’t simply cease, but transforms into something that can under certain conditions still interact with the living.” Katherine Frost, Daniel’s mother, never recovered from her son’s death. In testimony given to a researcher in 1865, she described the years following the tragedy.

I couldn’t accept what the doctors said happened. She explained, “It was too much, too impossible. But I also couldn’t deny that every prediction Daniel made came true. For years, I would sit in his empty room, hoping to hear his voice one more time, hoping he might speak to me from wherever he had gone.

But there was only silence.” Catherine died in 1867 at the age of 48. Those who attended her in her final illness reported that her last words were, “Daniel, is that you? I can hear you now.” In the 1860s, as America was torn apart by civil war, the case of Daniel Frost took on new significance.

The massive casualties of the war created an explosion of interest in spiritualism and communication with the dead. Mediums and seances became popular and many cited the Daniel Frost case as evidence that such communication was possible. Dr. Morrison, now elderly and in failing health, was troubled by this development.

In a letter written in 1869 to a colleague, he expressed his concerns. The charlatans and frauds who claimed to speak to the dead have seized upon Daniel’s story as validation for their deceptions, he wrote. But what happened with Daniel was not spiritualism or supernatural communication. It was something else.

Something that I believe has a rational scientific explanation, even if we lack the framework to understand it yet. Daniel wasn’t speaking from beyond death. He was speaking from within it, from a state that exists between life and death, where consciousness somehow persists even as the body fails. This is not mysticism.

It is biology we have yet to comprehend. Morrison’s distinction that Daniel was speaking from within death rather than from beyond it became an important one in later scientific discussions of the case. In the early 20th century, as medical understanding of consciousness and brain function advanced, researchers began re-examining historical cases of unusual death experiences.

The Daniel Frost case attracted new attention from neurologists and psychologists. Dr. Helena Ashworth, a pioneering neurologist at Johns Hopkins University, wrote extensively about the case in her 1923 book, Consciousness at the Threshold. Her analysis, based on modern understanding of brain function, offered a possible explanation.

The human brain can remain active for several minutes after the heart stops. Ashworth explained, “In rare cases, this period of activity may be extended by factors we don’t fully understand. temperature, oxygen levels in specific brain regions, or perhaps some unique aspect of an individual’s neurochemistry.

What makes the Daniel Frost case remarkable is not that his brain remained active after clinical death. We now know this is possible, but that he was able to speak clearly and coherently during this period. This suggests either that the medical determination of death was premature, or that Daniel’s brain had developed unusual pathways that allowed speech to continue without normal respiratory function.

But Ashworth’s rational explanation couldn’t account for Daniel’s accurate predictions. How could a dying brain predict events weeks in the future? How could it describe patients it had never met and prescribe treatments that wouldn’t be standard practice for decades? Ashworth acknowledged these limitations in her conclusion.

While we can now explain how speech might be possible during the dying process, we cannot explain the preient nature of Daniel’s statements. This remains one of the most puzzling aspects of the case. In 1947, exactly 100 years after Daniel’s death, Dr. Robert Chen, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital, conducted an extensive review of the case.

Using newly unsealed archives and forgotten documents, Chen reconstructed the events in unprecedented detail. His findings, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry added new dimensions to the mystery. Chen discovered that Daniel Frost had been born during a severe thunderstorm on March 15th, 1840. According to the birth records, which Chen located in a Cambridge church archive, Daniel had initially been declared stillborn.

The attending midwife recorded that the infant showed no signs of life for several minutes after birth. Chen wrote, “Only after repeated attempts at stimulation did the child draw his first breath.” The midwife noted in her records, “Unusual case. Child appeared dead but later revived. May bear watching.

” Chen also uncovered hospital records showing that Daniel had been admitted twice before his final illness. Once at age three after a near drowning incident and again at age 5 after a fall from a tree that left him unconscious for several hours. In both previous incidents, Chen noted witnesses reported that Daniel upon regaining consciousness spoke about events that hadn’t occurred yet.

The pattern was consistent, a near-death experience followed by a period of unusual perceptual abilities. Chen’s conclusion was controversial. Daniel Frost may have had a neurological condition that created an abnormal relationship between his consciousness and his body. This condition, triggered by trauma, may have allowed his conscious mind to persist and communicate even during states where normal physiological measures indicated death.

But even Chen couldn’t explain the predictions. He could only note that they occurred and that they were documented by credible witnesses. The most recent examination of the Daniel Frost case came in 2019 when Dr. Sarah Okonquo, a neuroscientist at MIT specializing in consciousness studies, applied modern theoretical frameworks to the historical evidence.

What’s most interesting about the Daniel Frost case from a contemporary perspective? Okonquo wrote in her paper historical anomalies in consciousness research is that it aligns with emerging theories about the nature of consciousness and time. Okonquo points to recent research suggesting that consciousness may not be entirely dependent on brain function that it might be in some sense a fundamental property of the universe that the brain processes rather than creates.

If consciousness is not generated by the brain, but rather interfaced through it, Okonquo explains, then cases like Daniel Frost’s become less impossible. The dying brain might under extraordinary circumstances interface with consciousness in novel ways, ways that transcend our normal experience of linear time and physical limitation.

Okonquo’s analysis also addresses the predictive elements. Modern physics tells us that time may not be as linear as we experience it. If Daniel’s dying brain somehow accessed consciousness in a way that transcended normal temporal constraints, his predictions might not have been supernatural, but rather the result of perceiving time from a different vantage point.

She concludes with a thought that echoes Dr. Morrison’s century old observations. Daniel Frost may have shown us something profound about the relationship between consciousness, the brain, and the nature of death itself. He may have demonstrated that the boundary between life and death is not as absolute as we believe. That consciousness in its dying moments may briefly access states of awareness that transcend our physical limitations.

Today, the case of Daniel Frost remains one of the best documented and most puzzling medical mysteries in American history. the original hospital records, witness testimonies, and doctor. Morrison’s detailed journals are preserved in the archives of the Massachusetts Medical Society. Several theories attempt to explain what happened in that operating theater in 1847.

Some propose that Daniel was not actually dead when he spoke, that the physicians, lacking our modern diagnostic tools, misidentified a state of deep unconsciousness as death. But this theory struggles to explain why three experienced physicians checking repeatedly all confirmed the absence of vital signs.

Others suggest that Daniel’s predictions were not truly predictive, but rather the result of rational inference by an unusually perceptive child. A dying boy with medical knowledge might predict that certain patients would arrive and suggest effective treatments. But this explanation cannot account for the specific details, names, dates, and circumstances that a 7-year-old child could not possibly have known.

The most intriguing theory advanced by consciousness researchers suggests that Daniel Frost may have experienced a rare neurological phenomenon where the dying brain entered a state that allowed it to access information through means we don’t yet understand. Perhaps through quantum effects in neural tissue, perhaps through mechanisms we haven’t discovered, Daniel’s consciousness may have briefly operated outside the normal constraints of time and space.

What we know for certain is this. On October 15th, 1847, 12 credible witnesses observed a dead child speak for 43 minutes. That child made specific predictions that all came true. And that child described the boundary between life and death as something permeable, something that consciousness could, under the right circumstances, traverse while remaining aware and communicative.

Doctor Morrison’s final journal entry written a week before his death in 1871 reflects on Daniel Frost one last time. I have spent 24 years trying to understand what happened that day. I have studied consciousness, death, the nature of the mind. I have attended to hundreds of dying patients, always watching, always listening, hoping to see again what Daniel showed me.

And I have reached a conclusion that would have seemed impossible to me in my youth. Death is not what we think it is. The sessation of heartbeat and breath marks a transition, not an ending. Consciousness does not simply extinguish like a candle flame. It transforms into something else. Enters a state we cannot see or measure with our instruments.

Daniel Frost was not a miracle or an anomaly. He was a messenger showing us a truth we were not ready to hear. That we are more than our beating hearts and breathing lungs. That consciousness is more resilient, more mysterious, and more powerful than we dare to imagine.

And sometimes at the very edge of death, that consciousness can speak to us one last time from the place between, trying to tell us that the boundary we fear so much is not a wall, but a threshold, not an ending, but a transformation into something we cannot yet comprehend. The impossible word spoken by a child who wasn’t breathing may have been trying to tell us something profound.

that death is not the absolute ending we believe it to be, but rather a doorway to a state of existence that consciousness can sometimes navigate while still maintaining a connection to the living world. And perhaps, just perhaps, Daniel Frost’s 43 minutes of impossible speech were a gift. A glimpse across that threshold meant to comfort us with the knowledge that consciousness, that essential spark of what makes us who we are, may be far more durable than the fragile flesh that houses it.

If this story has made you question what you thought you knew about the boundary between life and death, subscribe to our channel for more documented mysteries from history’s forgotten archives. Hit that notification bell because we never know when the next impossible case might challenge everything we believe about human consciousness and mortality.

Until next time, remember the most profound mysteries often hide in plain sight in the historical record, waiting to remind us that reality is stranger than we dare to imagine.