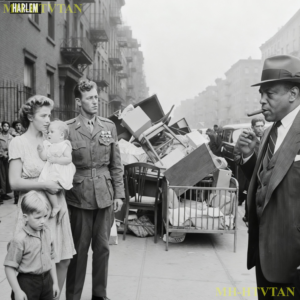

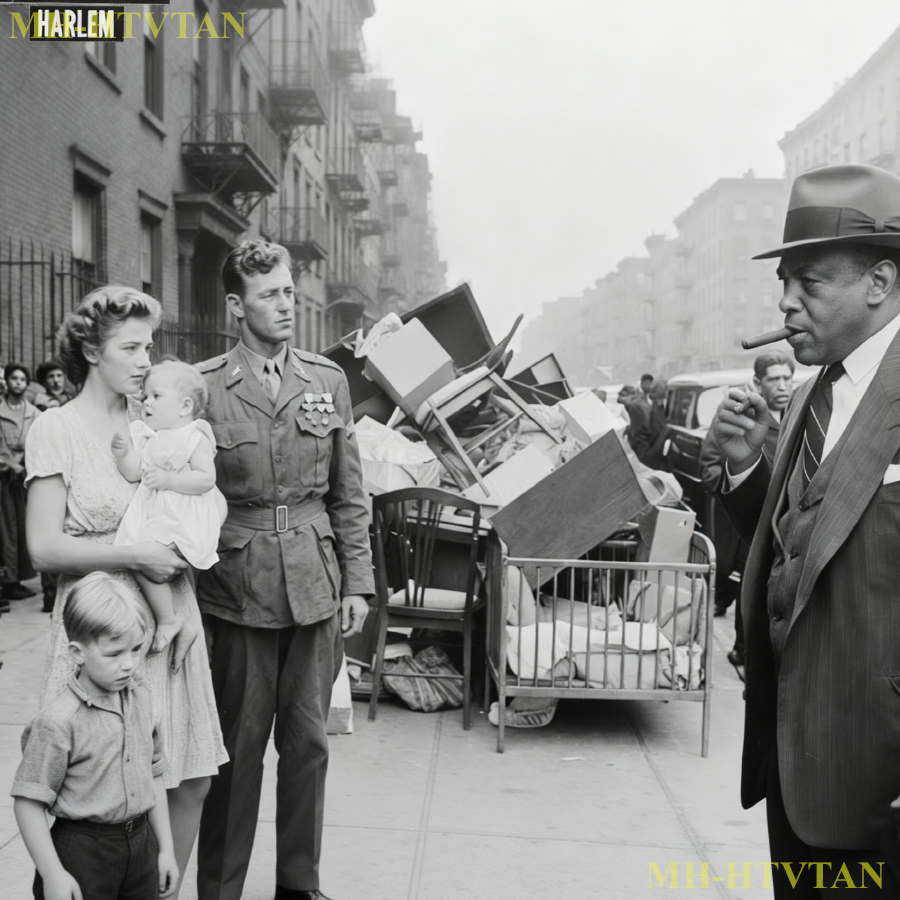

The furniture piled on sidewalk outside 347 West 118th Street at 9:23 a.m. on Thursday, November 21st, 1946, belonged to Staff Sergeant James Patrick O’ Connor, 28 years old, Bronze Star recipient, Purple Heart veteran who had served 18 months in European theater, including participation in Normandy invasion and Battle of the Bulge, where German artillery shell fragment embedded in his left shoulder left him with permanent partial disability and chronic pain, requiring regular medication, and whose wife Margaret Mary O’ Connor, 26

years old, and two children, Kevin Michael, age 4, and infant daughter Patricia Anne, born August 1946, just 3 months after Okconor finally returned home from military service, now sat on that furniture crying while their landlord, Samuel Goldstein, stood nearby with three hired men, ensuring that family’s belongings remained on street rather than being moved back inside apartment that Goldstein had just reclaimed through eviction notice served barely 72 hours earlier, citing Okconor’s inability to pay increased Ed rent that Goldstein

demanded upon learning that housing crisis gripping New York City and entire United States created sellers market allowing landlords to dramatically raise prices knowing that desperate families returning from war had no alternatives available in market where demand vastly exceeded supply.

This scene unfolding in morning sunlight on Harlem Street corner represented microcosm of massive housing crisis afflicting United States in aftermath of World War II when approximately 15 million service personnel returned home to nation experiencing worst housing shortage in American history resulting from combination of factors including 15 years of minimal construction during great depression and war years when war production board banned all non-defense construction.

construction directing building materials toward military needs. Massive internal migration bringing 9 million workers and their families to industrial centers for employment in war plants and returning veterans establishing families or expanding existing ones, creating unprecedented demand for housing units that simply did not exist because construction industry had essentially ceased civilian housing production since approximately 1931.

Congress recognized crisis severity declaring national housing emergency on May 22nd, 1946 with special executive branch powers intended to address situation that Wilson Wyatt estimated required 3 million new houses built during 1946 1947 period. But construction fell far short of demand, leaving hundreds of thousands of veteran families struggling to find any housing whatsoever, including resorting to living in hotels, basement, friends, spare bedrooms, converted barracks, quite huts, or even vehicles converted

into makeshift living quarters. This documentary examines intersection of housing crisis affecting World War II veterans, racial dynamics in 1940s Harlem, and complex moral character of criminal organizations. sometimes providing community protection when institutional systems failed citizens they ostensibly served.

Exploring how Bumpy Johnson’s intervention on behalf of white veterans family demonstrated principles transcending racial boundaries when confronting injustice against those who sacrificed defending nation. While we present these events for educational understanding about post-war American society and veteran struggles, we acknowledge that extrajudicial intervention by criminal organizations, regardless of positive outcomes in specific instances, existed within broader context of illegal activities causing harm to communities

and undermining legal institutions that should address such problems through legitimate channels providing systemic solutions rather than individual acts of charity. dependent on criminal power. Age restricted for mature audiences studying post-war housing crisis, veteran advocacy, racial relations in 1940s America, organized crimes, community role, and moral complexities arising when institutional failures create dependency on extrleal responses to legitimate grievances.

Bumpy Johnson’s presence on West 118th Street that November morning was coincidental rather than planned intervention, as he happened to be walking from breakfast meeting at small restaurant on Lennox Avenue back toward his office on 145th Street when he noticed crowd gathering around furniture on sidewalk and recognized situation as eviction, which had become increasingly common occurrence throughout Harlem and broader New York City as landlords exploited housing shortage to maximize profits through raising rents beyond

what working families could afford or evicting existing tenants to sell properties at inflated prices to desperate buyers willing to pay premiums for any available housing. Johnson was 41 years old in November 1946. Had been Harlem’s undisputed crime boss since approximately 1935 when he negotiated alliance with Lucky Luciano’s organization following Dutch Schultz’s murder and possessed sophisticated understanding of both economic dynamics driving housing crisis and moral obligations toward community members

experiencing hardship resulting from systemic failures rather than personal irresponsibility. The decision Johnson made to stop and investigate eviction rather than continuing to his office reflected his general pattern of monitoring street level developments in Harlem because intelligence about residents problems often provided strategic information useful for his operations while also allowing him opportunities to intervene in situations where his power and resources could address injustices that legal institutions ignored or

exacerbated through policies favoring property owners over tenants regardless of circumstances. Johnson’s approach to the scene involved positioning himself where he could observe without immediately drawing attention, allowing him to assess situation and determine whether intervention would be appropriate and effective before committing resources or reputation to action that might prove or counterproductive if underlying problems exceeded his capacity to address.

The conversation Johnson overheard between Margaret Okconor and landlord Goldstein revealed essential details about eviction circumstances, including that Okconor family had lived in apartment for 3 years since 1943 when Sergeant Okconor deployed to Europe, leaving pregnant wife and young son in housing he believed would remain available for duration of war and beyond.

that they had consistently paid rent on time using military aotment and Margaret’s wages from factory work she performed while husband served overseas. that Goldstein served eviction notice exactly 3 days after learning that citywide housing shortage created opportunities to triple rent charged for two-bedroom apartment that Okconor family occupied and that Okconor’s military disability payments combined with Margaret’s current wages from part-time work she could perform while caring for infant daughter were insufficient to meet new rent demands

that Goldstein justified by claiming he needed to cover increased property taxes and maintenance costs. though his actual motivation involved maximizing profit from crisis affecting families who had no alternatives. Have you witnessed landlords exploiting crises to extract maximum profit from vulnerable families who lack power to resist economic coercion? Subscribe and comment about situations where property owners prioritized personal enrichment over basic human decency toward tenants who had fulfilled all legitimate obligations

but found themselves victimized by market dynamics beyond their control. The detail that captured Bumpy Johnson’s attention and transformed his observation into intervention was moment when four-year-old Kevin O’Conor asked his mother why they were sitting outside with their furniture. And Margaret’s response through tears explained that they had to leave their home because daddy came back from war hurt and couldn’t work as much as before, meaning they couldn’t afford the new rent that Mr. Goldstein demanded, even though they

had always paid what they owed when Daddy was fighting Germans to keep America safe. This explanation crystallized situations fundamental injustice in ways that transcended racial boundaries Johnson typically navigated. Because regardless of Kevin O’Connor<unk>’s white skin and Sergeant Okconor’s Irish Catholic background differing from Johnson’s black identity and secular worldview, the principle at stake involved whether community would tolerate exploitation of wounded veteran whose service defending nation entitled

him to better treatment than being evicted on the street with wife and two small children because landlord prioritized profit over decency. The values Johnson brought to his assessment of Okconor family’s situation reflected complex moral code he maintained throughout his criminal career.

Combining ruthless pragmatism about necessary violence protecting his interests with genuine concern for community welfare and personal honor code requiring intervention against certain categories of injustice regardless of whether such intervention provided direct strategic benefits to his organization. Johnson had never served in military himself because his extensive criminal record and multiple prison sentences during 1920s and early 1930s made him ineligible for service even if he had been inclined to volunteer. But he possessed deep respect

for military service resulting partly from recognition that black soldiers willingness to fight for nation that denied them equal rights. Demonstrated courage and patriotism exceeding what white citizens typically displayed and partly from strategic understanding that veteran community represented significant voting block and potential allies in various political and economic struggles affecting Harlem’s residents.

The initial intervention Johnson executed involved approaching Margaret Okconor directly while Goldstein was temporarily distracted, supervising his hired men, stacking furniture, introducing himself politely as local businessman who happened to witness eviction, and wondered whether family had anywhere to go or any resources to secure alternative housing.

Margaret’s response revealed she had heard Johnson’s name, but knew little specific about his activities beyond vague awareness that he was important person in Harlem, who commanded respect from residents and fear from those who crossed him, and her desperation overcame any concerns she might otherwise have about accepting assistance from known criminal, whose help might carry strings or expectations she couldn’t afford to accept.

The information Margaret provided during brief conversation included that Sergeant O’ Conor was currently at Veterans Administration office attempting to resolve problems with his disability payments that had been delayed due to bureaucratic errors requiring multiple visits and extensive paperwork.

That family had approximately $47 in savings after paying month’s rent just 18 days earlier before learning about Goldstein’s tripling of rent demands and that Margaret’s sister in Queens had offered temporary refuge. But sister’s husband opposed taking in family of four indefinitely because his own apartment was barely adequate for his own wife and three children.

Johnson’s decision about how to address Okconor family’s crisis involved calculating both immediate practical assistance and longerterm solution, ensuring that famil family’s housing security wouldn’t remain dependent on continued criminal charity, but rather would be established through sustainable arrangement they could maintain independently once Sergeant Okconor’s VA benefits and employment situation stabilized.

The immediate action Johnson took involved instructing Margaret to have family remain with furniture while he made phone calls addressing situation. Then walking to pay phone on corner where he contacted three different people whose cooperation would be necessary for implementing plan he developed during brief conversation assessing family circumstances and resources.

The first call Johnson made was to Joseph Joey Bats Betaglia, Italian-American associate who owned several residential buildings throughout Harlem and Washington Heights through legitimate property investment company that also served as vehicle for laundering proceeds from various illegal gambling operations. Johnson’s organization conducted under protection arrangement with Genevie’s crime family.

Johnson’s request to Battalia was straightforward. Identify available two-bedroom apartment in building with reasonable landlord who wouldn’t exploit tenant vulnerability. arranged for Okconor family to move in immediately with first month’s rent and security deposit covered by Johnson personally as loan to be repaid when Sergeant Okconor’s financial situation improved and ensure that ongoing rent would be set at rate Okconor could afford based on his current disability payments and Margaret’s part-time wages rather than

inflated market rates that housing crisis made possible for unscrupulous landlords to charge. The second call Johnson placed was to Bernard Benny the Book Rosen Jewish attorney who provided legal services to Johnson’s organization while maintaining legitimate practice handling civil matters for Harlem residents who paid modest fees or sometimes received pro bono representation when Rosen determined their cases involved injustices deserving remedy regardless of clients inability to pay. Johnson’s instructions

to Rosen involved researching whether Sergeant Okconor might have legal grounds for challenging Goldstein’s eviction based on rent control ordinances that Congress had imposed in March 1946, specifically to prevent landlords from exploiting housing emergency by charging excessive rents, investigating whether Okconor qualified for emergency housing assistance through programs federal government established for returning veterans, and exploring whether Goldstein’s aggressive rent increases and rapid eviction might

violate any tenant protection laws that could provide basis for lawsuit seeking damages or at minimum creating enough legal pressure to discourage Goldstein from similar exploitation of other veteran families in buildings he owned. The third call Johnson made was to Malcolm Little, 21-year-old street hustler who Johnson had mentored since approximately 1943 when Little arrived in Harlem and quickly gained reputation as intelligent young man whose articulate speech and sharp analytical mind suggested potential for greater

achievements than typical criminal career. Despite his current involvement in various illegal activities, including drug dealing, numbers running, and burglary operations, Johnson’s request to Malcolm involved organizing crew to move Okconor family’s furniture from sidewalk to storage facility Johnson maintained for various purposes.

ensuring that belongings were protected while permanent housing arrangement was finalized and having Malcolm personally accompany Okconor family to whatever temporary accommodation Johnson secured until apartment battalia identified became available for occupancy. The execution of Johnson’s plan unfolded over approximately 6 hours following his initial phone calls during which time Margaret and children remained on sidewalk with furniture while Johnson returned to provide updates and reassurance that situation was being

addressed though he declined to specify details about who was helping or what arrangements were being made because Margaret’s ignorance about Johnson’s criminal operations provided her with plausible deniability if authorities he’s ever questioned her about assistance she received. The practical manifestation of Johnson’s intervention included storage truck arriving at 12:47 p.m.

to collect furniture for secure storage at facility on 132nd Street. Malcolm Little and two associates escorting Okconor family to small hotel on 135th Street where Johnson had arranged three nights accommodation with meals included while permanent housing was finalized and Joey Betaglia identifying suitable two-bedroom apartment in building on West 145th Street where Irish Catholic superintendent who himself was World War II veteran responded positively to Battalia’s explanation about Okconor family’s circumstances and agreed to set reasonable rent, reflecting what

disabled veteran could sustainably afford. If you’ve seen criminal organizations providing community services that government institutions failed to deliver despite official responsibility, hit like and subscribe for more stories exploring complex relationships between illegal power structures and legitimate community needs, creating situations where residents sometimes relied on criminals for protection and assistance that legal systems theoretically should provide but practically didn’t.

Sergeant James Okconor’s return to his family at Hotel on 135th Street occurred at approximately 5:30 p.m. that evening when he finished frustrating day at Veterans Administration office where bureaucrats informed him that processing delays affecting his disability payments would require additional 4 to 6 weeks for resolution due to paperwork complications involving his medical records and discharge documentation.

Meaning that family’s financial crisis would continue indefinitely unless he secured employment despite physical limitations preventing him from performing manual labor that represented most accessible work for men with his limited education and lack of professional skills beyond military training.

Okconor<unk>’s initial reaction to learning that unknown benefactor had intervened to address family’s eviction combined gratitude with suspicion about why stranger would assist white Irish Catholic family in Harlem where racial dynamics typically created barriers rather than bridges between white residents and black power structures controlling neighborhoods economic and social systems.

The meeting arranged between Johnson and Okconor occurred that evening at small restaurant where Johnson conducted informal business meetings with associates and community members seeking assistance or offering information. And the conversation between two men revealed both commonalities and differences shaping their respective worldviews and moral frameworks.

Okconor’s military service had exposed him to racial integration in ways that many white Americans never experienced because wartime necessity forced armed forces to gradually reduce segregation barriers that had historically prevented black soldiers from serving alongside white troops.

and Okconor’s bronze star resulted partly from actions during firefight where black soldier from different unit provided covering fire that saved Okconor’s squad from German ambush that would likely have killed or captured them all. This experience created an Okconor perspective recognizing that courage and character transcended racial boundaries.

Though he retained many prejudices absorbed from Irish-American community where he was raised and where casual racism represented normalized aspect of social interactions and political discourse. Johnson’s explanation to Okconor about why he intervened to prevent families homelessness focused on principle rather than personal connection, stating that man who served nation in combat and earned bronze star defending liberty deserved better treatment than being evicted onto street by landlord exploiting housing crisis for profit and

that Johnson’s power in Harlem carried responsibilities, including using that power to address injustices affecting community members regardless of whether victims shared his racial identity or could offer anything valuable in exchange for assistance provided. The arrangement Johnson proposed to Okconor involved several components.

First family would occupy apartment Joey Battalia identified with first three months rent covered by Johnson as interestf free loan to be repaid when Okconor’s financial situation stabilized through combination of disability payments resuming and employment income from whatever work Oconor could perform given his physical limitations.

Second, attorney Benny Rosen would provide free legal representation investigating whether Okconor had grounds for lawsuit against Goldstein seeking damages for illegal eviction or excessive rent increases violating emergency rent control ordinances. Third, Johnson would leverage his connections with several Harlem businesses to identify employment opportunities suitable for wounded veteran whose shoulder injury prevented heavy lifting, but whose intelligence and reliability made him valuable employee for various operations

requiring trustworthy personnel. The moral complexity underlying Johnson’s intervention involved acknowledging that his assistance to Okconor family existed within broader context of criminal empire built on illegal gambling, protection rackets, and various other activities causing harm to Harlem residents whose poverty and desperation made them vulnerable to exploitation by numbers, bankers, lone sharks, and other predators operating under Johnson’s protection or direct control.

Okconor<unk>’s acceptance of Johnson’s help required him to recognize that sometimes survival necessitated accepting assistance from morally compromised sources and that refusing help based on benefactors criminal activities would constitute luxury. That man responsible for wife and two young children couldn’t afford when alternative involved homelessness during approaching winter when temperatures dropping below freezing could literally kill his family if they lacked adequate shelter and heating. The relationship

that developed between Johnson and Okconor over subsequent months transcended initial transaction of landlord intervention and housing assistance evolving into mentorship where Johnson provided Okconor with strategic guidance about navigating bureaucratic systems affecting veterans while Okconor offered Johnson perspective about white workingclass experiences and attitudes that informed political dynamics affecting Harlem and broader New York City.

The employment Johnson arranged for Okconor involved working as manager at small warehouse operation that served as legitimate front business for Johnson’s criminal enterprises, where Okconor’s responsibilities included inventory management, shipping coordination, and employee supervision, performing tasks that didn’t require physical labor beyond his capabilities, while paying wages sufficient to support his family once combined with disability payments that finally resumed in January 1947.

7 after Benny Rosen filed formal complaints with congressional representatives whose intervention accelerated VA processing addressing delays affecting thousands of veterans throughout nation. The longerterm impact of Johnson’s intervention extended beyond simply preventing one family’s homelessness to establishing precedent and reputation affecting how Harlem community perceived Johnson’s character and values despite widespread knowledge about his criminal activities.

The story about black crime boss helping white veterans families spread through both white and black communities in neighborhood, creating narrative challenging simplistic racial stereotypes, while also raising complex questions about why criminal organization provided assistance that government institutions failed to deliver despite official responsibility for supporting veterans who had sacrificed defending nation.

The political implications of Johnson’s action included enhanced legitimacy and moral authority that complicated efforts by law enforcement and reform politicians to characterize him as simple predator whose elimination would benefit community because residents understood that Johnson’s criminal enterprises coexisted with genuine commitment to community welfare manifesting in interventions like protecting Okconor family alongside more publicized acts of charity.

including distributing food during holidays and providing financial assistance to families experiencing emergencies. The legal investigation Benny Rosen conducted regarding Okconor’s eviction revealed that Goldstein had indeed violated emergency rent control ordinances limiting how much landlords could increase rents during national housing emergency.

and Rosen filed lawsuit in December 1946, seeking monetary damages for illegal eviction plus injunction preventing Goldstein from imposing similar rent increases on other tenants in buildings he owned throughout Harlem. The case settled in March 1947 with Goldstein paying Okconor family $800 compensation and agreeing to reduce rents he had raised for 17 other families in his properties, demonstrating how single intervention by Johnson triggered broader consequences, protecting additional families from exploitation. That legal system should

have prevented proactively but only addressed reactively after private attorney funded by criminal organization forced issue into courts that otherwise would have ignored tenants complaints about landlord abuses. However, celebrating Johnson’s assistance to Okconor family requires acknowledging profound moral tensions about whether criminals acts of charity somehow compensate for or justify broader patterns of harm his organization inflicted on Harlem community through gambling operations, extracting wealth from residents who could least afford

losses, through violence maintaining his criminal empire and eliminating competitors or threats to his authority, and through corruption of police and political systems that should have served public interest, but instead protected criminal enterprises in exchange for bribes and political support.

Okconor himself wrestled with these contradictions, recognizing that man who saved his family from homelessness and provided employment enabling him to support wife and children was simultaneously responsible for contributing to neighborhoods problems through illegal activities that federal, state, and city governments struggled ineffectively to suppress despite periodic enforcement campaigns producing arrests and convictions, but never fundamentally disrupting criminal enterp enterprises that adapted and persisted across decades of attempted

suppression. The broader historical context of Johnson’s intervention, situating it within patterns of organized crime, providing social services, and community protection that government institutions failed to deliver, has been extensively documented by historians examining how Italian mafia, Irish gangs, and black criminal organizations often functioned as informal governments in urban neighborhoods where official authorities were either absent, hostile, or incompetent.

This pattern created morally complicated relationships between criminals and communities they simultaneously protected and exploited because residents understood that declining criminal assistance or cooperation might result in losing access to resources and protection while accepting such help created dependency and obligation that criminals leveraged for their own purposes, including shielding themselves from law enforcement by cultivating community support that complicated efforts to prosecute them or dismantle.

their operations. The question whether Okconor’s gratitude toward Johnson and his willingness to testify on Johnson’s behalf during 1952 federal narcotics trial represented genuine appreciation for assistance received or constituted form of coerced loyalty resulting from power imbalance between criminal benefactor and vulnerable family dependent on his continued goodwill.

reflects larger debates about nature of obligation and reciprocity in relationships characterized by profound inequality. Okconor’s testimony describing Johnson as man of honor who helped veteran family when government abandoned them contributed to jury’s apparent reluctance to convict Johnson despite substantial evidence of his involvement in heroin distribution network.

Though ultimately Johnson received 15-year sentence after appeals process exhausted legal challenges to conviction based partly on government’s argument that Okconor’s testimony reflected calculated attempt by sophisticated criminal to cultivate character witnesses whose grateful testimonials might persuade juries to overlook overwhelming proof of guilt.

The institutional failures that created situations requiring criminal intervention for veteran families to secure housing included Congress’s delayed response to housing crisis despite clear warnings before wars end about inevitable shortage facing returning servicemen, inadequate funding for emergency housing construction programs that fell far short of demand, ineffective rent control enforcement allowing landlords to violate regulations with minimal consequences.

and Veterans Administration’s bureaucratic incompetence processing disability claims, leaving thousands of wounded veterans without promised benefits while they struggled to survive with families dependent on incomes reduced by service related injuries. These systemic problems reflected broader patterns of American government’s tendency to provide rhetorical support for military personnel while simultaneously failing to deliver adequate practical assistance during transitions from wartime service to civilian life. Creating gaps between

national mythology, celebrating veterans as heroes and material reality of their experiences. navigating bureaucracies that treated them as burdensome administrative problems rather than citizens deserving priority consideration for sacrifices they made. The moral lesson derable from Johnson’s intervention in Okconor family’s housing crisis involves recognizing that acts of charity or justice performed by individuals engaged in criminal activities don’t erase broader harms their illegal enterprises cause, but

rather demonstrate complex truth that human moral character resists simple categorization into neat dichotoies of good versus evil or hero versus villain. Johnson was simultaneously community protector and predator, defender of vulnerable families, and perpetrator of violence and exploitation, principled man of honor within criminal codes constraints, and ruthless operator prioritizing his organization’s interests over legitimate institutions authority.

Understanding this complexity requires abandoning comfortable narratives, celebrating criminals as folk heroes fighting unjust systems, while also resisting equally simplistic condemnations, ignoring genuine protective functions they performed when legal institutions failed communities depending on them for basic security and welfare.

If you’ve considered how institutional failures create dependency on extraleal power structures providing services government should deliver, subscribe for more stories exploring impossible moral choices communities face when choosing between accepting criminal assistance and enduring official neglect. Tell us in comments whether you think Johnson deserves recognition for helping Okconor family or whether such acts simply constitute public relations efforts by criminals seeking to obscure their fundamentally destructive impact on neighborhoods they

control. The Okconor family’s eventual departure from Harlem occurred in 1952 when James secured employment at manufacturing company in Queens, offering wages sufficient to afford housing outside neighborhood where they had lived since 1943. and their move represented broader pattern of white flight from Harlem that accelerated during 1950s as black population increased and white residents relocated to suburbs or outer burough neighborhoods perceived as offering better schools, safer streets, and more prosperous futures for their children.

Okconor maintained occasional contact with Johnson until Johnson’s 1963 release from Alcatraz, exchanging Christmas cards and occasional phone calls, updating each other about family developments and sharing observations about how Harlem changed during decade when Okconors built comfortable middle-class life in Queens.

While Johnson served federal prison sentence resulting partly from case where Okconor’s testimony failed to prevent conviction despite genuine appreciation and respect expressed toward defendant. The legacy of Johnson’s intervention affecting how Okconor raised his children included teaching them that character transcends racial boundaries and that prejudices their Irish-American community took for granted represented moral failures preventing recognition of common humanity connecting people regardless of skin color or ethnic

background. Kevin O’Connor later served in Vietnam War and credited his father’s stories about how black crime boss saved their family and how black soldier saved his father’s squad during World War II with shaping his rejection of racism prevalent among white working-class communities during 1960s when civil rights struggles forced Americans to confront systemic discrimination that many white citizens preferred ignoring because acknowledging such problems required accepting complicity and oppression and committing to changes

threatening comfortable arrangements benefiting them at others expense. The broader historical significance of stories like Johnson’s assistance to Okconor family involves demonstrating how exceptional circumstances sometimes produced moments of cross-racial solidarity, transcending typical patterns of segregation and mutual suspicion, characterizing relations between black and white workingclass communities during midentth century America.

These moments remained exceptional rather than representative, occurring when specific combinations of individual character, immediate circumstances, and underlying values aligned in ways producing outcomes defying prevailing racial hierarchies and stereotypes that both black and white Americans internalized through socialization in fundamentally racist society that treated racial categorization as natural and inevitable rather than socially constructed.

and perpetually contested through daily interactions and political struggles reshaping meanings and material consequences of racial identity across generations. The question whether celebrating Johnson’s intervention risks romanticizing criminal who caused substantial harm while ignoring institutional reforms necessary to prevent situations requiring extraleal responses reflects ongoing debates about how societies should remember complex historical figures whose legacies combine admirable actions with reprehensible conduct. The challenge

involves maintaining intellectual honesty about both dimensions of Johnson’s character and impact while using his story to illuminate broader patterns of institutional failure, community resilience, and moral complexity characterizing urban America during 20th century when rapid social changes and persistent inequalities created conditions producing both terrible injustices and inspiring examples of human solidarity, transcending boundaries that racial capitalism imposed to maintain oppressive hierarchies serving elite

interests while dividing workingclass communities that might otherwise unite for mutual benefit. The story of Bumpy Johnson helping white veterans family during postwar housing crisis ultimately represents parable about values transcending racial boundaries about institutional failures forcing impossible choices and about moral complexity resisting simplistic categorization.

Understanding this history requires holding multiple contradictory truths simultaneously. Johnson performed genuinely admirable act helping Okconor family. Johnson’s criminal career caused substantial harm to Harlem community. Okconor<unk>’s gratitude was justified and sincere. Celebrating Johnson’s charity risks obscuring his destructive activities.

Institutional reforms were necessary but insufficient alone to address community needs. Criminal organizations filled service gaps, government left, but also perpetuated problems requiring those services. The lesson for contemporary audiences involves recognizing that functioning societies must provide equal justice and adequate support for all citizens, including military veterans, through legitimate institutions, rather than creating situations where communities depend on criminals to enforce standards and provide assistance

that law should guarantee, but historically hasn’t delivered consistently or fairly across racial and economic divides, continuing to define and deform American democratic aspirations. ations.