In September 1972, two geological surveyors stumbled upon something that would rewrite American history and challenge everything we thought we knew about isolation, family, and the darkness that fers in complete seclusion. Deep in the Appalachian wilderness of eastern Kentucky, they discovered the Darington Estate, a sprawling property that had been completely cut off from civilization since 1840.

What they found wasn’t just an abandoned homestead. It was a living, breathing nightmare that had sustained itself for over 130 years. The family had developed their own language, their own rituals, and their own twisted interpretation of survival. But the most disturbing discovery wasn’t how they lived.

It was why they chose to disappear in the first place, and what they’d been protecting all these years. This is the story of America’s most isolated family and the dark secret that isolation was meant to preserve. The compass was lying. That’s what Thomas Huitt kept telling himself as he watched the needle spin uselessly in his palm, rotating in slow, sickening circles that defied every law of magnetic north he’d ever learned.

Beside him, his surveying partner, Malcolm Strad, was on his knees, vomiting into the underbrush for the third time in an hour. They were 12 miles deep into uncharted Appalachian territory, and something was very, very wrong. The assignment had seemed routine when the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources handed them the contract 3 weeks prior.

Map the mineral deposits in the unexplored eastern ridge of Harland County. mark potential sites for future development returned with coordinates and soil samples. Standard work for two men who’d spent the better part of a decade trudging through America’s forgotten wilderness. But this place felt different from the moment they’d crossed the treeine that morning.

The forest here was old in a way that made Thomas’s skin crawl. Not old like the carefully preserved national parks where tourists took pictures and children learned about photosynthesis. This was something older, something that predated the neat categories modern forestry had tried to impose on the natural world.

The trees grew at angles that seemed to defy gravity, their trunks twisted into spirals that reminded Thomas of rungout towels. The underbrush was so dense in places that they’d had to hack through it with machetes. and the air itself felt thick, almost liquid, as though they were walking through something’s breath rather than oxygen and nitrogen.

No birds sang here. That was the first thing Malcolm had noticed, and once he’d pointed it out, the silence became oppressive, a physical presence that pressed against Thomas’s eard drums until they achd. They’d been arguing about turning back when Malcolm had spotted the fence. It appeared suddenly through a break in the foliage, and for a moment Thomas thought his eyes were playing tricks on him.

But no, there it was, unmistakable despite its age, and the way nature had tried to reclaim it. A stone wall perhaps 6 ft high, stretching east and west as far as they could see through the trees. The stones were massive, each one easily 3 ft across, fitted together with the kind of precision that spoke of serious labor and serious purpose.

Someone had built this thing to last, and to keep something either in or out. The wall was covered in moss and lyken, cracked in places where tree roots had forced their way through, but still fundamentally intact after what must have been more than a century of neglect. Thomas ran his hand along the cold stone, feeling the texture of it, the tiny fossils embedded in the rock that spoke of ancient seas and geological epochs that made human history seem like a brief, forgettable footnote.

There were marks carved into some of the stones, symbols that might have been letters or might have been something else entirely. They were weathered almost to invisibility, but Thomas could still make out what looked like warnings, though in what language he couldn’t say. Malcolm had pulled out the survey maps, spreading them across a fallen log and running his finger along the topographical lines, searching for any indication that this structure should exist. Nothing.

According to every official record, they were standing in pristine unmapped wilderness. No settlements, no historical sites, no indication that human hands had ever touched this land. That should have been their cue to document the finding and retreat, to report back to the department and let someone with more authority make the decision about what to do next.

But Thomas had never been good at following the sensible course of action. And Malcolm, despite his current state of intestinal distress, was just curious enough to be dangerous. They’d followed the wall north for nearly 3 hours, watching as it curved and bent with the natural contours of the land, clearly designed by someone who understood the terrain intimately.

The craftsmanship was remarkable, even to Thomas’s untrained eye. Whoever had built this had been thinking in terms of generations, not years. This was meant to stand long after its creators were dust. The gate appeared around midafter afternoon and with it the first real evidence that they’d stumbled into something beyond their understanding.

It was massive, constructed from the same gray stone as the wall with iron hinges that had rusted into abstract sculptures of oxidation and decay. But it wasn’t the gate itself that made Thomas’s blood run cold. It was what was hanging from it. Dozens of small bundles, each one carefully wrapped in what looked like oil cloth, suspended from the iron bars by lengths of rope that had somehow resisted complete decomposition.

Malcolm had approached one of the bundles slowly, reaching up to touch it with fingers that trembled despite his best efforts at composure. The oil cloth crumbled at his touch, revealing what lay inside. Bones. Small bones. Bird skeletons. rabbit skulls, the delicate frameworks of squirrels and possums and other creatures Thomas couldn’t immediately identify.

Each one had been carefully arranged, positioned with obvious care into poses that suggested ritual rather than random disposal. But that wasn’t the worst part. The worst part was that some of the bundles were fresh. The rope on several of them showed no sign of weathering, and when Malcolm had gathered the courage to examine another, the bones inside were still held together by desiccated tissue, the smell of decay recent enough to make both men gag.

Someone was still maintaining this place. Someone was still performing whatever dark ritual these offerings represented. The realization hit them simultaneously, and they’d both taken an involuntary step backward, away from the gate, away from the implications of what they were seeing. Malcolm’s face had gone white, and Thomas could feel his own heart hammering against his ribs in a rhythm that felt too fast, too urgent, as though his body was preparing for flight before his mind had fully processed the danger. They should have left then.

Every instinct Thomas possessed was screaming at him to turn around, to retrace their steps, to get back to the safety of map territory and electric lights, and the comfortable illusion that the modern world had banished this kind of primordial dread to the history books. But the gate was a jar, just slightly, just enough to suggest entry, as though whoever had last passed through hadn’t bothered to secure it properly, or perhaps as though they were expecting visitors.

Thomas found himself moving toward the opening before he’d consciously made the decision. His feet carrying him forward while his mind shouted objections that his body refused to acknowledge. Malcolm grabbed his arm, fingers digging in hard enough to bruise, but Thomas shook him off with a violence that surprised them both. Beyond the gate, the forest changed.

The oppressive density of the undergrowth gave way to something that might have once been cultivated land, though nature had been slowly reclaiming it for decades. There were rows still visible beneath the wild growth, suggesting crops that had been planted with systematic precision. An orchard of some kind spread to the east.

The trees, gnarled and heavy with fruit that looked wrong somehow, too dark, too uniform, hanging from branches that seemed to reach toward the ground rather than the sky. The path beyond the gate was still discernable, worn into the earth by generations of feet, leading upward through the gradually thinning trees towards something Thomas couldn’t quite make out through the afternoon haze.

They walked in silence, both men too frightened and too fascinated to speak. The path was lined with more stones, smaller than those in the wall, but still precisely placed, forming a border that channeled them forward like water through a pipe. Thomas noticed scratch marks on many of these stones, deep grooves that looked like they’d been made by something with claws, though what animal could have scored rock that deeply? He didn’t want to imagine.

Every 50 f feet or so they passed wooden posts driven into the ground. Each one topped with something that made Thomas’s stomach clench. More bones, yes, but also other things. Scraps of cloth, twisted pieces of metal, and in one case what looked disturbingly like a human tooth. Yellowed with age, but unmistakable in its shape and origin.

The house revealed itself gradually like something emerging from water. First just a suggestion of straight lines where nature provided only curves, then corners, the sharp angles of human construction asserting themselves against the organic chaos of the forest. Finally, the full structure came into view, and both men stopped dead, their breath catching in their throats.

It was enormous, a sprawling complex of buildings that seemed to have grown together over time. Additions built onto additions until the original structure was lost somewhere in the architectural evolution. The main building was three stories tall, constructed from the same gray stone as the wall with narrow windows that looked less like openings to let in light and more like slits designed for defense.

The roof was slate, still largely intact, despite what must have been decades of exposure to the elements, and chimneys rose from various points along its length like accusing fingers pointing at an uncaring sky. But it was the state of the place that truly disturbed Thomas. It wasn’t abandoned. That would have been explicable, even comforting in its way.

Another forgotten homestead. Another failed attempt at taming the wilderness. another family that had given up and moved on to easier lives in the growing cities. No, this place was maintained. The windows were intact. The stonework showed signs of recent repair, and smoke, thin, gray, barely visible in the afternoon light, was rising from one of the chimneys. Someone lived here.

Someone was home. After more than 130 years of isolation, after existing beyond the reach of every census and every map, after presumably surviving without contact with the outside world through the Civil War, the Industrial Revolution, two world wars, and the complete transformation of American society, someone was still here, still maintaining this impossible fortress of solitude, still performing the rituals that left bones hanging from the gate.

Malcolm had the camera out now, his hands shaking so badly that Thomas doubted any of the pictures would be usable. But procedure was procedure, and documenting this discovery was technically their job, even if every fiber of Thomas’s being was urging him to run, to forget they’d ever seen this place, to let it remain hidden for another century, or however long it took for someone braver or more foolish to stumble across it.

The clicking of the camera shutter seemed obscenely loud in the silence, and Thomas found himself holding his breath after each click, waiting for a response from the house, for doors to burst open and angry voices to demand explanations, but nothing happened. The house stood silent, watching them with its narrow window eyes.

The smoke continuing its lazy ascent from the chimney, utterly indifferent to the intrusion. They were circling around to the eastern side of the structure when they saw the gardens. Acres of them stretching out in carefully maintained rows, vegetables, and herbs growing in patterns that suggested deep knowledge of companion planting and crop rotation.

Someone had been tending these plots recently. Thomas could see fresh tool marks in the soil. Could see where plants had been recently harvested, their stumps still oozing sap. And beyond the gardens, something else. Stone markers, dozens of them, arranged in neat rows that could only mean one thing, a graveyard. But these weren’t the weathered lykancovered monuments of an abandoned cemetery.

These stones were clean. Some of them looked recent. And as Thomas and Malcolm approached, they could see that many bore dates that made no sense, that violated everything they thought they understood about this place. The oldest stone they could find was dated 1841, just one year after the family would have had to arrive to build the wall and the house.

The name carved into it was weathered, but still legible. Jeremiah Darington, patriarch and protector. But there were newer stones, too. stones that couldn’t possibly be real. That suggested births and deaths occurring long after any reasonable person would assume the family line had died out. A stone dated 1923, another from 1957, and most disturbing of all, one dated 1969, just 3 years ago, bearing the name Patients Darington with only a birthy year carved beneath it, no death date, suggesting that whoever she was, she might still be

alive, might be watching them from one of those narrow windows, even now. Thomas was so focused on the gravestone that he didn’t hear the footsteps until they were almost upon him. Malcolm’s strangled gasp of warning came half a second too late. Thomas spun around and found himself face to face with something that his mind struggled to categorize as human.

The figure was tall, impossibly thin, dressed in clothes that looked like they’d been handwoven from some coarse gray fabric. The face was wrong. Not deformed exactly, but asymmetrical in a way that suggested generations of isolation, of a gene pool that had become a gene puddle, of bodies adapting to circumstances that no human body should have had to adapt to.

The eyes were the worst part, pale gray and enormous, bulging slightly from the skull, and they fixed on Thomas with an intensity that felt almost physical. As though the stranger’s gaze was pressing against his skin, the figure opened its mouth, and sound emerged, but it wasn’t language as Thomas understood it.

The words, if they were words, seemed to bypass his ears entirely and lodged directly in his brain, creating sensations more than meanings, impressions of warning and curiosity, and something else, something darker that Thomas didn’t want to examine too closely. He took a step backward, then another, his hand reaching blindly for Malcolm, needing the confirmation that he wasn’t alone in witnessing this impossibility.

But Malcolm was already running, his surveying equipment forgotten, the camera swinging wildly from its strap around his neck as he crashed back through the gardens toward the gate. Thomas wanted to run, too. Wanted to follow Malcolm’s example and flee back to the world of compasses that pointed north and people whose eyes were the right size for their skulls.

But his legs wouldn’t obey, wouldn’t respond to the panic signals his brain was broadcasting. The figure took a step closer, and Thomas could smell it now. Not the smell of unwashed flesh. Though there was that, too, but something else, something organic and ancient, like the forest itself had taken human form and come to investigate the intruders.

The figure raised one long-fingered hand, pointing not at Thomas, but past him towards something behind him. And Thomas felt his blood turned to ice water in his veins, because he knew, knew with absolute certainty that he didn’t want to see what was behind him. That looking would be a mistake he’d regret for whatever remained of his life, but he looked anyway.

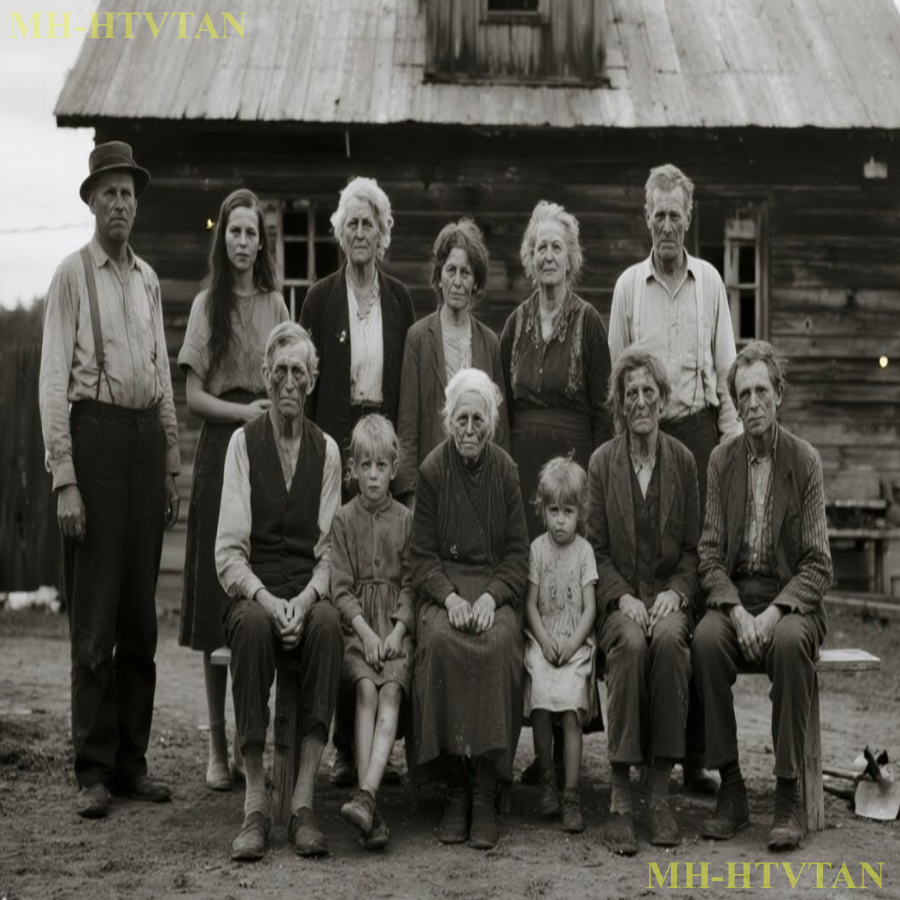

He turned slowly, fighting every instinct that screamed at him to keep his eyes forward, and saw them. Dozens of figures emerging from the house, from the forest, from places he couldn’t identify. All of them sharing that same quality of wrongness, that same sense of being human adjacent rather than fully human. Men, women, children.

At least he thought some of them were children, though their proportions were off in ways that made age difficult to determine. They were all dressed in that same gray fabric, all watching him with those same unsettling eyes. And they were all utterly silent, creating a tableau that felt more like a painting than reality, frozen in a moment that stretched and stretched until Thomas thought he might go mad from the tension of it.

Then one of them spoke, and unlike the first figure, this one’s words were comprehensible. Though the accent was strange, the vowels elongated in ways that suggested a dialect that had evolved in isolation, cut off from the natural linguistic drift that contact with other speakers would have provided. “You should not have come here,” the speaker said, and it took Thomas a moment to realize it was a woman, her voice surprisingly young, despite the weathered quality of her face.

The boundary is marked. The warnings are clear. Yet you have crossed. And now the choice must be made. Thomas tried to respond. Tried to explain that they were just surveyors just doing their jobs, that they meant no harm, and would leave immediately and never speak of this place to anyone.

But his mouth wouldn’t form the words. and he realized with growing horror that he was crying, tears streaming down his face while his body remained locked in place, unable to flee, unable to fight, unable to do anything but stand and wait for whatever came next. Malcolm hadn’t stopped running until his lungs felt like they were filled with broken glass, and his legs finally gave out beneath him, sending him sprawling into the undergrowth two miles from the Darington estate.

He lay there gasping, his face pressed into the damp earth, and tried to convince himself that what he’d seen was real, that his mind hadn’t finally cracked under the pressure of too many years, spent in isolated places where the line between civilization and wilderness blurred into nothing. But the camera around his neck was solid and real.

And when he finally found the courage to look at it, he saw that the lens was shattered, spiderwebed with cracks that made the device useless. He couldn’t remember hitting it against anything during his flight, which meant something else had broken it, something he didn’t want to think about too carefully. Thomas hadn’t followed him. That realization came slowly, filtering through the panic and the adrenaline, and with it came a guilt so profound that Malcolm thought he might vomit again.

He’d abandoned his partner, had left him standing there, surrounded by those things, and now Malcolm was alone in the forest with darkness coming on and no idea how to find his way back to their base camp. Thomas, meanwhile, had been taken inside. Not roughly. There had been no violence, no physical coercion. Instead, the crowd of Daringtons had simply parted, creating a path toward the main house, and the woman who had spoken had gestured for him to follow.

The alternative, her eyes suggested, would be significantly less pleasant, and Thomas found himself walking, his feet moving mechanically, while his mind reeled from the impossibility of everything around him. The interior of the house was dark despite the afternoon sun outside. The narrow windows admitting only thin shafts of light that illuminated dancing dust moes and revealed glimpses of a world that seemed to exist outside of time.

The walls were stone like the exterior, but covered in places with hangings made from that same gray fabric he’d seen on the Darington’s clothing. The hangings depicted scenes that Thomas’s eyes refused to fully process. Figures engaged in activities that might have been farming or might have been something else entirely.

The proportions all wrong, the perspective skewed in ways that made his headache when he tried to focus on them. They led him through a series of corridors that seemed to wind back on themselves, creating a maze that Thomas knew he’d never be able to navigate alone. He tried to count turns, to memorize landmarks, but the sameness of it all defeated him.

Every corridor looked like every other corridor. Every door was identical to its neighbors, and the few distinguishing features he could find seemed to shift when he wasn’t looking directly at them, as though the house itself was rearranging to prevent memorization. Finally, they emerged into a large room that must have been at the center of the structure.

a space that rose two stories and was lit by oil lamps that cast flickering shadows across walls covered in more of those disturbing hangings. There was a table in the center of the room, massive and made from a dark wood that looked almost black in the lamplight, and around it sat what Thomas assumed were the elders of the clan, seven figures of indeterminate age, who watched him with expressions that managed to convey both curiosity and complete indifference to his fate.

Some woman who had spoken outside, gestured for Thomas to sit in a chair that had been positioned facing the table, and he did so. His legs, grateful for the restbite, even as his mind continued to scream warnings about his situation. One of the elders leaned forward, and Thomas saw that this one was male, though age had worn away most of the obvious gender markers, leaving a face that looked like it had been carved from the same stone as the house itself.

“Your name,” the elder said, and it wasn’t a question, Thomas told him, his voice sounding strange and distant in his own ears. And the elder nodded slowly, as though Thomas’s name confirmed something he’d already suspected. and you have come from the outside,” the elder continued, and again it wasn’t a question, but Thomas nodded anyway, some instinct telling him that cooperation was his only path to survival.

The elers’s eyes, those same disturbing pale gray eyes that seemed to be universal among the Daringtons, narrowed slightly. “The outside has forgotten us,” he said, and there was something in his tone that Thomas couldn’t quite identify. satisfaction perhaps or relief or possibly disappointment. For 132 years we have maintained the boundary and for 132 years no one has crossed it until today.

Another elder spoke, this one female, her voice higher and thinner than the first speakers. The question is why? She said, and Thomas heard others around the table murmuring agreement. The boundary is marked. The warnings are clear. Only those seeking what should not be sought would cross such obvious barriers.

Thomas tried to explain about the survey, about the Department of Natural Resources, about mineral rights and geological assessments and all the mundane bureaucratic reasons that had brought him to this place. But the words sounded hollow even to his own ears, and he could see from the elders expressions that they either didn’t understand or didn’t believe him.

The concept of governmental organizations methodically mapping every inch of territory seemed to be completely foreign to them. And Thomas realized that of course it would be. They had isolated themselves before such things existed before the federal government had grown powerful enough to care about what happened in forgotten corners of Appalachia.

A third elder, younger than the others, but still clearly holding authority, leaned back in his chair and steepled his fingers in a gesture that seemed bizarly modern given the medieval atmosphere of the room. “You carry instruments,” he said, and Thomas noticed for the first time that his surveying equipment had been taken, was now laid out on the table in front of the elders like evidence in a trial.

Instruments for measuring, for mapping, for recording. You were making a record of our location. It wasn’t an accusation exactly, but it wasn’t neutral either, and Thomas felt his throat tighten with fear. Yes, he admitted, because lying seemed both pointless and potentially more dangerous than the truth.

“But we didn’t know you were here. According to all our maps, this area is uninhabited wilderness.” The elder smiled at that and it was possibly the most disturbing expression Thomas had seen on any human face. Uninhabited, the elder repeated. Yes, that is the word we have worked so hard to ensure remains true, uninhabited, unmapped, unknown.

The woman who had first spoken outside moved to stand beside the elders, and Thomas realized she must be important despite her relative youth. The instruments can be destroyed, she said, addressing the elders rather than Thomas. The records he carries can be burned. But the man himself, the man is a problem that destruction alone cannot solve.

There was silence after that, heavy and oppressive, and Thomas felt sweat beginning to run down his back despite the coolness of the stone room. They were discussing whether to kill him. The realization came with absolute clarity, and with it came the understanding that his death would solve their problem neatly. No witness, no record, nothing to suggest the Darington estate existed at all.

Malcolm might make it back to civilization, might report what he’d seen, but without Thomas to corroborate his story without photographs, without any physical evidence. He’d be dismissed as someone who’d gotten lost in the woods and let his imagination run wild. But the eldest of the elders, a figure so ancient that Thomas couldn’t determine gender, even with careful observation, raised a withered hand for silence.

There is another consideration. The ancient one said, voice barely above a whisper, yet somehow carrying clearly through the room. The outside has changed. We know this from the rare artifacts that wash down the streams, from the sounds that sometimes carry on the wind. The world beyond our boundary is not the world we left in 1840.

If we kill this surveyor, others will come looking. They will have better instruments, more resources. Our isolation, which has been our strength, may now be our vulnerability. The other elders shifted uncomfortably, and Thomas sensed disagreement, tension in the hierarchy that his presence had disrupted.

The patriarch warned against contact, another elder said, and Thomas noticed several of the Daringtons around the room making gestures at the mention of this title, touching their foreheads and chests in what was clearly a ritual sign of respect or protection. Jeremiah Darington established the boundary for reasons that remain valid today.

The contamination of the outside. The ancient one cut him off with a sharp gesture. Jeremiah Darington has been dead for 131 years, the Ancient One said, and there was steel in that whispered voice. Now, his wisdom guides us, yes, but we cannot pretend the world is unchanged. This man before us is proof that the outside has advanced beyond what Jeremiah could have imagined.

We must adapt or we will be discovered regardless of our wishes. The debate continued, and Thomas listened with growing horror as he began to understand the nature of the Darington isolation. They hadn’t simply retreated from society. They had fled from something specific, something they called contamination, and their entire existence for more than a century had been structured around maintaining absolute separation from whatever that contamination represented.

References were made to the old ways and the preservation and the bloodline. Each phrase delivered with reverent intensity that suggested religious significance. Finally, the ancient one spoke again, and the others fell silent immediately, suggesting a hierarchy based on age or wisdom or possibly something else entirely.

Thomas Huitt, the ancient one said, and hearing his name in this place spoken by this impossible figure made his skin crawl. You have crossed the boundary and witnessed what should not be witnessed. By the old laws, your life is forfeit. But these are not the old times, and we must consider new approaches to old problems. Therefore, we offer you a choice.

Thomas’s heart hammered against his ribs. A choice meant alternatives, meant possibility, meant maybe he wouldn’t die in this stone room, surrounded by these strange, wrong people. You may leave, the Ancient One continued, and Thomas felt hope flare in his chest. But if you leave, you must first understand what you are leaving behind, what you are promising to protect through your silence.

You must be shown the truth of the Darington estate, the reason for our isolation, and the consequences should that isolation be broken. The woman stepped forward again, and Thomas saw her clearly for the first time in the lamplight. She was young, probably no more than 25, but her eyes held something older, something that suggested she’d seen things that aged the soul faster than the body.

“My name is Patience Darington,” she said, “and Thomas remembered the gravestone he’d seen, the one dated 1969 with no death year. “I am the current keeper of records. and it will be my task to show you what we are, what we’ve preserved, and what we’ve sacrificed to maintain our separation from your world.” She moved closer to him, close enough that he could smell that strange organic scent again, and her voice dropped to barely above a whisper.

“But I warn you now, Thomas Huitt, once you have seen, you cannot unsee. The knowledge we will share is not a gift but a burden. Many who have borne it have wished they had chosen death instead. Thomas wanted to refuse, wanted to demand they simply let him go, that he’d promise anything they wanted if they’d just allow him to walk back through that gate and never return.

But he knew it wasn’t a real choice. They would show him whatever dark secret they’d been protecting. and his silence afterward would be ensured not by his word, but by his horror, by his desperate desire to forget what he’d learned. “I’ll look,” he said finally, his voice steadier than he felt. “I’ll listen, and then I’ll leave, and I’ll never speak of this place to anyone.

” Patience studied him for a long moment, those pale eyes seeming to see directly into his skull, measuring his sincerity, or perhaps his capacity for discretion. Then she nodded slowly and turned to the elders. It is decided then, she said. I will take him to the archive. He will see the records.

He will understand, and then we will determine whether he leaves in silence or in pieces. The elders rose as one, their chairs scraping against the stone floor with a sound-like bones grinding together. They filed out through a door behind the table, moving with surprising speed despite their apparent age, and soon Thomas was alone with patients and two younger Daringtons who stood by the doors.

Clearly guards despite their lack of obvious weapons. Patients walked to one of the walls and did something Thomas couldn’t quite see, pressing stones in a sequence that caused a section of wall to swing inward, revealing a descending staircase that looked like it had been carved directly into the bedrock beneath the house.

“The archive is below,” patient said, lighting a lamp from one of those already burning in the room. It has been kept since the first year of our isolation. Every birth, every death, every significant event in the history of the Darington clan has been recorded there. But more importantly, it contains the reason, the true reason that Jeremiah Darington brought his family to this place and built walls to keep the world out.

They descended into darkness, the lamplight pushing back shadows that seemed to resist illumination. They clung to the corners and edges like living things reluctant to be dispelled. The stairs went down much further than Thomas would have thought possible, down past what must have been the foundation of the house, down into the mountain itself.

The temperature dropped with each step, and the air grew thick with moisture and something else, a smell that reminded Thomas of libraries and museums and other places where time accumulated in physical form. Finally, the stairs ended in a chamber that took Thomas’s breath away, despite his fear. It was enormous, stretching away into darkness beyond the reach of patients’s lamp, and every wall was lined with shelves, and every shelf was packed with books and scrolls and loose papers that represented more than a century of meticulous recordkeeping.

Patients set the lamp on a table near the stairs, and gestured for Thomas to sit. Then she walked to one of the shelves and selected a large leatherbound volume that looked older than anything Thomas had ever seen outside of a museum. She carried it back to the table with reverence, handling it like it was made of spider silk and prayers.

This is the journal of Jeremiah Darington, she said, opening the book to reveal pages covered in cramped careful handwriting. He began it in 1839, one year before he brought his family to this place. He continued it until his death in 1841. It is the foundation of everything we are, everything we believe, everything we’ve sacrificed to preserve.

She turned pages slowly, and Thomas caught glimpses of diagrams and calculations and long passages written in a language he didn’t recognize. Finally, she stopped at a page near the middle of the journal and turned the book so Thomas could read it. The entry was dated March 15th, 1840, and it began with words that made Thomas’s blood run cold.

“The contamination has reached Philadelphia,” Jeremiah had written. “I have seen it with my own eyes, have watched as men and women of good character transform into something less than human, their very essence corrupted by proximity to the source. The doctors call it progress. The philosophers call it enlightenment.

The industrialists call it the future. But I know what it truly is. It is the death of the soul, the replacement of human spirit with mechanical thinking, the reduction of God’s greatest creation to mere cogs in an infernal machine. I will not allow my family to be consumed by this transformation. I will take them far from the cities, far from the railroads and factories and all the trappings of this new age.

I will build a place where the old ways can be preserved, where human beings can remain truly human, where the contamination cannot reach. Thomas looked up at patience. Confusion momentarily overwhelming his fear. He was afraid of industrialization. He asked, “Of progress? That’s why you’ve isolated yourselves for over a century, because your ancestor didn’t like factories.

” But patience was shaking her head, a sad smile on her face. That’s what I thought too when I first read these journals as a child, she said. I thought Jeremiah was simply mad, a paranoid man who dragged his family into the wilderness based on delusions. But there’s more, much more. The contamination he wrote about wasn’t metaphorical.

She turned more pages, moving forward through the journal to entries from later in 1840, after the family had arrived at what would become the Darington Estate. Read this,” she said, pointing to an entry dated September 3rd, 1840. “Read it carefully.” Thomas leaned over the page, squinting in the lamplight. “We have been in this place for 3 months,” Jeremiah had written.

“The walls are complete. The house is habitable, and I believe we are safe, at least for now. But the transformation that I witnessed in Philadelphia has followed us, has found us, even here in our isolation.” Last night, my youngest son, William, came to me with a revelation. He had been exploring the caves beneath the mountain, and had found something, a vein of awe unlike any he had seen before, dark and crystalline, that seemed to pulse with its own internal light.

He had touched it, and immediately knew things, understood things that no 12-year-old child should be capable of understanding. He spoke to me of machinery that hasn’t been invented yet, of discoveries that haven’t been made, of a future that stretches beyond anything I could imagine. The awe had given him this knowledge, had pushed it directly into his mind, and when I examined William myself, I saw the change.

His eyes had begun to take on that same distant quality I’d seen in the factory workers, that suggestion of something looking out from behind the human face. I have sealed the caves. I have forbidden anyone from approaching that cursed ore. But I fear it may already be too late. Thomas sat back, his mind racing. He found something under the mountain, he said slowly.

Something that affected them, changed them. Patience nodded, and her expression was grim. That’s correct, she said. And it didn’t stop with William. One by one, members of the family were drawn to the caves, were exposed to what we now call the influence. It changed them in ways that Jeremiah couldn’t prevent, couldn’t reverse.

It gave them knowledge they shouldn’t have, understanding of things beyond their time. But it also changed them physically, slowly across generations. The eyes you’ve noticed, the proportions that seem wrong. Those are the accumulated effects of 132 years of exposure to the influence. We are no longer entirely human, Thomas Hewitt.

We are something else, something that can see further and understand more deeply than your kind, but at a cost that Jeremiah spent his life trying to prevent. She turned more pages, showing him entries where Jeremiah detailed his growing horror as he watched his family transform as he realized that the isolation he’d sought to protect them from industrialization had instead exposed them to something far more dangerous.

He tried everything, prayer, physical barriers, even attempting to lead the family away from the estate entirely. But the influence had its hooks in them by then, and they couldn’t leave. couldn’t abandon the source of their transformation even though they understood intellectually that it was destroying their humanity. By the end, patient said, showing Thomas the final entries in Jeremiah’s journal, he understood that there was only one path forward, complete isolation, absolute separation from the outside world.

Not to protect us from contamination, but to protect the world from us. Because the knowledge the influence grants the understanding of future technologies, future events, if that were to leak into the broader world, if others were to find this place and experience what we’ve experienced, it could accelerate human history in ways that would be catastrophic.

Thomas felt like he was falling, like the stone floor beneath him had opened up to reveal infinite depth. “You’re saying you can see the future,” he said. And it wasn’t a question because he already knew it was true. Had already accepted it the moment he saw those eyes. That wrongness that suggested these people existed slightly outside of normal human time.

Not exactly. Patience corrected. We can see possibilities, trajectories, the logical outcomes of current actions. The influence doesn’t show us a fixed future, but rather helps us understand the patterns, the mathematics of causality in ways that make prediction almost trivial. And yes, over the generations, as the changes have accumulated, that ability has grown stronger.

There are elders who can look at you and know with reasonable certainty how you’ll die, what choices you’ll make, what legacy you’ll leave. She closed Jeremiah’s journal and selected another volume, this one more recent. This is my journal, she said. I began it in 1965 when I turned 16 and took on the role of keeper of records. Let me show you what I’ve seen about your world, about the future that’s coming for your civilization.

She opened to a page covered in diagrams and notes. And Thomas recognized immediately that he was looking at designs for technology that didn’t exist yet, or if it did, wasn’t publicly known. “I’ve never left this estate,” patient said quietly. “I’ve never seen a television or driven a car or used a telephone.

But I can draw you schematics for computers that won’t be commercially available for another decade. I can describe political events that haven’t happened yet. I can tell you the names of presidents who haven’t been elected. Not because I’m prophetic, but because the influence lets me see the patterns. Lets me understand the trajectories.

And this knowledge, Thomas Huitt, this is why we’ve stayed hidden. Because if your government, your military, your corporations knew what existed under this mountain, knew what could be gained by exposure to the influence, they would come here in force. They would expose themselves to it, would gain the knowledge we have, and they would use it in ways that would reshape history itself.

Thomas stared at the diagrams at the impossible knowledge contained in this journal written by a woman who’d never left a 19th century estate in the Appalachian wilderness. The elders debated killing you, patients continued, because that would be simplest. But I argued for this instead for showing you the truth because I’ve seen the pattern of your life, Thomas Huitt.

I know you’re a man who keeps his promises. I know you understand the weight of responsibility. I know that once you’ve seen what I’ve shown you, once you understand what’s at stake, you’ll do everything in your power to ensure this place remains hidden. She leaned forward, and her eyes seemed to glow in the lamplight, seemed to contain depths that human eyes shouldn’t possess.

The question is, was I right about you, or should I have let them kill you when they wanted to? Thomas didn’t sleep that night, though the Daringtons had provided him with a room in one of the outer buildings, a small stone chamber with a narrow bed and a single window that looked out over the darkened forest.

They’d returned his equipment, minus the compass, which they said had been too contaminated by proximity to the influence to function properly anymore. And they’d fed him a meal of vegetables from the garden and meat from animals Thomas couldn’t identify and didn’t want to ask about. patients had left him at the door to his temporary quarters with a final warning that he should not attempt to leave during the night, that the boundary was patrolled, and that the Daringtons who performed that duty were not bound by the same restraint the elders showed. Thomas

believed her. He’d seen the way some of the younger clan members looked at him with a hunger that had nothing to do with food and everything to do with the fact that he represented a threat to their isolated existence. Instead of sleeping, he sat on the bed and tried to process what he’d learned in the archive.

His mind kept returning to those diagrams in patients’s journal. to the casual way she’d described technology that shouldn’t exist, events that hadn’t happened, knowledge that no isolated family should possess. Part of him wanted to dismiss it all as elaborate fantasy, as the delusions of people who’d been cut off from reality for so long that they’d constructed an entire mythology to justify their isolation.

But he’d seen those eyes, had felt something in the air of this place that defied rational explanation, and deep down he knew that patience was telling the truth. There was something under the mountain, something that had been changing the Daringtons for more than a century, and that something granted, knowledge at the cost of humanity itself.

The question that kept Thomas awake was simpler and more immediate than the metaphysical. implications of the influence. Would they actually let him leave? Patients had said she’d seen the pattern of his life, had claimed to know he would keep their secret. But what if she was wrong? What if the elders overruled her? What if, despite all the talk of choices and possibilities, they’d already decided his fate and was simply going through the motions of civility before carrying out an execution.

He had no way to defend himself, no weapon beyond his surveying equipment, which would be useless against people who’d spent their entire lives in this wilderness. And even if he could somehow fight his way out, the forest itself seemed to be their ally, seemed to shift and change in ways that would make escape nearly impossible for someone who didn’t know its secrets.

Dawn came slowly, the gray pre-son light filtering through his window and revealing that someone had been standing outside his door all night. Thomas could see the shadow through the gap at the bottom, could hear the soft sound of breathing that suggested a guard, who’d been instructed to ensure he didn’t attempt an unauthorized departure.

When full daylight finally arrived, the shadow moved away, and moments later there was a knock at the door. Thomas opened it to find a young Darington man, probably no more than 18, with those same disturbing eyes, and that same quality of wrongness that marked all the clan members. Patience requests your presence, the young man said, his voice oddly formal, as though he’d learned English from books rather than conversation.

She wishes to show you the source before you depart. the source, the influence itself, the thing under the mountain that had transformed the Daringtons across five generations. Thomas felt his stomach clench with fear and something else. Curiosity, maybe, or that same self-destructive impulse that had led him through the gate in the first place, instead of following Malcolm back to safety.

“Lead [clears throat] the way,” Thomas said, and followed the young man out into the morning air. The estate looked different in daylight, less threatening somehow, though no less strange. He could see more of the clan members now, going about their daily tasks, tending the gardens, repairing buildings, engaging in activities that looked almost normal until you noticed the way they moved.

Slightly too fluid, slightly too coordinated, as though they were all following choreography only they could perceive. Children played in a cleared area near one of the outbuildings, but their games were wrong. Involved patterns and rules that made no sense to Thomas’s observation, and their laughter had a quality that made his skin crawl, patience was waiting near the main house.

Dressed in the same gray homespun fabric, but with a leather satchel slung over her shoulder. She nodded to Thomas as he approached and dismissed the young guard with a gesture. “Did you sleep?” she asked, though her tone suggested she already knew the answer. Thomas shook his head, and she smiled slightly. “No, I didn’t think you would.

What you learned yesterday is not the kind of knowledge that permits rest.” She started walking, not toward the house, but rather toward the eastern edge of the estate, where the forest pressed close against the cleared land. “The entrance to the caves is this way,” she said over her shoulder. Jeremiah sealed the main opening in 1841, shortly before his death.

But there are other ways in ways that we’ve used to monitor the influence, to study it, to try to understand what it is and what it wants from us.” They walked in silence for perhaps 20 minutes, following a path that was barely visible through the undergrowth. Thomas noticed that patients moved with the same fluid grace as the other clan members, placing her feet with precision that suggested she could have navigated this route blindfolded.

The forest here felt different than it had on his approach to the estate. The trees were older, more twisted, and there was that same oppressive silence he’d noticed before, as though every bird and animal had learned to avoid this particular stretch of wilderness. The influence extends beyond the caves, patients said, apparently sensing his thoughts.

Its reach is limited, perhaps 2 miles in any direction from the source. But within that radius, everything changes. Plants grow in unusual patterns. Animals either flee or become something else entirely, and people people receive the knowledge, but at an increasing cost. The cave entrance was hidden behind a rockfall that looked natural, but which Thomas suspected had been carefully arranged to disguise the opening.

Patience moved several of the larger stones aside with surprising strength, revealing a gap just wide enough for a person to squeeze through. She lit a lamp from her satchel and gestured for Thomas to follow her into the darkness. The passage beyond was narrow and low forcing them to move in a crouch, and the air had a quality that Thomas associated with deep places, with spaces that had never known sunlight.

The stone walls were damp with condensation, and in the lamplight Thomas could see formations that looked like they might be natural geological features, except for their regularity. their suggestion of intentional design by something that understood geometry in ways that human architects didn’t. After what felt like an eternity of cramped passage, but was probably only 10 minutes, the tunnel opened into a larger chamber, and patients stood upright holding the lamp high.

The light revealed a space perhaps 30 ft across with a ceiling that disappeared into darkness above them. But it was the far wall that drew Thomas’s attention and made his breath catch in his throat. The ore that Jeremiah had written about was there, a vein of dark crystalline material that seemed to absorb light rather than reflect it, creating a patch of darkness that was somehow darker than the surrounding shadows.

And it was moving, or at least giving the impression of movement. subtle shifts in its surface that suggested it was breathing, living, aware of their presence. “Don’t touch it,” patient said sharply, grabbing Thomas’s arm as he took an involuntary step forward. “Direct contact is dangerous for those not already changed by it.

The knowledge comes too fast, too overwhelming.” Jeremiah’s son, William, was never quite right after his first exposure, and he’d been born to a family that had at least some resistance. For someone like you, with no previous contact, it could destroy your mind entirely,” Thomas pulled back, suddenly aware that he’d been moving toward the ore without conscious decision, drawn by something he couldn’t name.

“What is it?” he asked, his voice barely above a whisper. “Where did it come from?” Patients moved closer to the vein, though she was careful not to touch it. “We don’t know,” she admitted. Jeremiah theorized it might be a meteorite, something that fell from the sky long before humans settled this continent. Others in the clan have suggested it’s terrestrial, but from deep in the earth, brought to the surface by volcanic activity millions of years ago.

What we do know is that it’s not natural, not in any sense that geology recognizes. The patterns in its structure suggest artificial construction, though by what or whom we can’t begin to guess. She opened her satchel and pulled out what looked like a small journal, different from the large volumes in the archive. This is more recent, she said, flipping through pages covered in notes and diagrams.

My observations over the past 7 years, the influence is getting stronger, Thomas. Whatever it is, wherever it came from, it’s not static. It’s growing, expanding its reach, becoming more active. When Jeremiah first found it in 1840, it was dormant, barely detectable. Now, standing this close to it, can you feel it? Thomas realized that he could.

There was a pressure in his head, a sense of information trying to push its way into his consciousness, of doors in his mind that were being tested by something that wanted entry. He could almost grasp it, almost understand what the ore was trying to communicate. And the temptation to let those doors open, to receive whatever knowledge the influence wanted to share, was nearly overwhelming.

This is why we can never leave,” Patient said, watching his face carefully. “This is why we’ve sacrificed everything to maintain our isolation. Because if the outside world discovered this, if your government or your scientists or your military got their hands on it, they would use it. They would expose themselves to the influence, would gain the knowledge it offers, and they would think themselves masters of fate, able to predict and control the future.

But they wouldn’t understand the cost until it was too late. The influence doesn’t just give knowledge. It replaces what makes us human with something else. something that can see further and understand more, but that has lost the capacity for things like mercy, compassion, spontaneity. The elders you met yesterday are barely human anymore, Thomas.

They’re vessels for the influence, repositories of knowledge, and prediction, but empty of everything that makes life worth living. She closed the journal and tucked it back into her satchel. “I’m 25 years old,” she said quietly. By clan standards, that makes me young, still mostly human, despite the changes that have accumulated through my lineage.

But I can feel it working on me, feel myself becoming less emotional, more analytical, more aware of patterns and possibilities, and less able to care about them. In another 20 years, I’ll be like the elders, functional, knowledgeable, and fundamentally broken in ways that matter more than any physical deformity.

This is what we’re protecting your world from, Thomas Huitt. Not our knowledge, but the source of that knowledge. The influence that would spread like a disease through your civilization if it were ever discovered. Thomas tore his eyes away from the dark crystalline vein and looked at patients. In the lamplight, he could see something in her expression that hadn’t been there before.

vulnerability maybe or sadness or the last remnants of purely human emotion before the influence finished its work on her. Then why show me? He asked. Why bring me down here? Why let me see this if the whole point is to keep it secret? Patience smiled, and for a moment she looked like what she should have been, a young woman in the prime of her life, full of possibility and hope.

Then the moment passed and she was once again something other, something that existed between human and whatever the influence was creating. Because you need to understand what you’re protecting, she said. You need to see it, feel it, comprehend on a visceral level what would happen if this secret got out. Words aren’t enough.

Jeremiah’s journal isn’t enough. You needed to stand in this cave and feel the influence pressing against your mind and realize how seductive it is, how easily people would convince themselves that the knowledge is worth the cost. She started back toward the tunnel entrance, and Thomas followed, grateful to be leaving the chamber and that oppressive presence behind.

As they moved through the narrow passage, patient spoke again, her voice echoing oddly in the confined space. Your partner, Malcolm Straoud, he made it back to your base camp. We’ve been watching him. He’s terrified, traumatized, and he’s planning to report what he saw the moment he gets back to civilization. But without you to corroborate his story without photographs or physical evidence, he’ll be dismissed as someone who got lost and let fear warp his memories.

The department will send another surveying team eventually, but we’ll be ready for them. will make sure they find nothing, see nothing, suspect nothing. This estate will remain a blank spot on your maps. A place that surveyors somehow always avoid without quite understanding why. They emerge from the cave into daylight that seemed painfully bright after the darkness below.

Patients replaced the stones over the entrance with practice deficiency, and soon there was no sign that the cave existed at all. You’ll leave this afternoon, she said as they walked back toward the main house. We’ll escort you to the boundary and point you toward your base camp. You’ll find Malcolm there, and you’ll help him write a report that explains your absence without mentioning us.

You’ll attribute your experiences to heat exhaustion, dehydration, perhaps a minor head injury that caused hallucinations. whatever story makes sense to your superiors. And then you’ll go back to your life, Thomas Huitt. And you’ll never speak of this place again because you understand now what’s at stake.

Thomas wanted to argue, wanted to insist that he couldn’t simply pretend the Darington estate didn’t exist, that his conscience wouldn’t allow him to hide this discovery from the world. But even as the thoughts formed, he knew he would do exactly what patients described. He’d seen the influence, felt its pull, understood the danger it represented.

The knowledge it offered was too seductive, too powerful, too destructive to be allowed into the broader world. Better that the Daringtons continue their lonely vigil, continue their slow transformation into something posthuman, than risk exposing humanity to a force that would fundamentally alter the species. How long can you maintain this? he asked as they reached the estate proper.

How long can you stay hidden in a world that’s mapping every inch of the planet that has satellites and aerial photography and computers that will eventually locate every structure, every anomaly? Patients considered the question as they walked through the gardens. Honestly, I don’t know. The influence shows me possibilities, but the future isn’t fixed.

There are timelines where we’re discovered within the next decade where the secret gets out and everything I’ve warned you about comes to pass. There are others where we successfully hide for another century where my great grandchildren continue the isolation long after I’m gone. And there are even timelines where the influence itself solves the problem where it grows powerful enough to actively defend against discovery.

though what it would become by that point is beyond even my ability to predict. She stopped walking and turned to face him fully. What I do know is that every person who discovers us and chooses to keep our secret increases the probability that we remain hidden. You’re not the first, Thomas. Over the years, there have been hunters, travelers, people who stumbled across the boundary and saw things they shouldn’t have seen.

Some we killed when we had no choice. Others we showed the truth as I’ve shown you and trusted them to understand what was at stake. So far that trust has been justified. So far the secret has held. They’d reached the main house and Thomas could see several of the elders gathered near the entrance, watching their approach with those unsettling pale eyes.

There’s one more thing you need to see before you go, Patient said, leading him not into the house but around to its eastern side where Thomas hadn’t yet explored. There was another building here, smaller than the main house, but still substantial, constructed from the same gray stone. Patients opened the heavy wooden door, and gestured for Thomas to enter.

The interior was dim, lit only by narrow windows high in the walls, but as Thomas’s eyes adjusted, he realized he was standing in something like a nursery. There were cribs, small beds, toys carved from wood, and in the center of the room. Sitting in a rocking chair was an elderly woman holding. They walked in silence, and Thomas realized that Malcolm was crying, tears streaming down his face as they put distance between themselves and that impossible place.

Thomas put an arm around his partner’s shoulders, offering what comfort he could, and together they made their way back toward civilization, toward normaly, toward lives that would never be quite the same, despite their best efforts to forget what they had seen. Behind them, the gate closed with a sound like a tomb ceiling, and Thomas didn’t look back.

didn’t want his last sight of the Darington estate to replace the image of baby hope that was already seared into his memory. A reminder of the price that isolation demanded and the tragedy that continued generation after generation in the darkness beyond the boundary. Thomas Hwitt never spoke of the Darington estate to anyone except Malcolm Straoud, and even between them the subject became something approached with extreme caution, discussed only in private moments when they were certain no one could overhehere. Their official

report to the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources described a routine surveying expedition complicated by equipment failure and a brief period of disorientation caused by dehydration and heat exhaustion. The mineral deposits in the eastern ridge were deemed insufficient to warrant further exploration, and the area was quietly removed from future development consideration.

No one questioned their conclusions. No one suggested a follow-up expedition. The Darington estate remained unmapped, undiscovered, protected by the mundane bureaucracy of governmental indifference as much as by its own isolation. But Thomas kept the stone, that small piece of the influence wrapped in cloth and hidden in a locked drawer in his home office.

He told himself it was just a reminder, just a physical object to ground the increasingly dreamlike quality of his memories. But late at night, when sleep wouldn’t come, and the weight of the secret pressed too heavily on his chest, he would take out the wrapped stone and hold it, feeling through the cloth that subtle vibration that suggested awareness, presence, intention.

And sometimes in those dark hours he would catch glimpses of things. Not clear visions exactly, but impressions, possibilities, patterns that suggested futures both beautiful and terrible, depending on choices not yet made. The influence was still working on him, he realized, even through the barrier of cloth and distance.

Once you’d been exposed, once you’d stood in that cave and felt it pressing against your mind, you were never entirely free of it. Malcolm had tried to move on more completely, had taken a transfer to a different department, and thrown himself into work that kept him far from any unmapped wilderness. They’d met for drinks occasionally in the months after the discovery.

But the conversation had been strained, artificial, both men dancing around the thing they couldn’t discuss, while trying to maintain the friendship they’d built over years of working together. Eventually, the meetings had tapered off, and Thomas understood why. Malcolm wanted to forget, needed to forget, and Thomas’s presence was a constant reminder of knowledge that couldn’t be unlearned.

The last time they’d spoken had been in early 1973. A brief phone call where Malcolm had mentioned he was getting married, moving to Ohio, starting fresh in a place with no memories of Appalachian forests and families that shouldn’t exist. Thomas had congratulated him and wished him well, and they’d both known they would never speak again.

The years passed, and Thomas continued his work, surveying other territories, mapping other wilderness areas, always careful to steer clear of the eastern ridge, where the Darington estate waited in its timeless isolation. He married eventually, had two children, built a life that looked from the outside like the normal existence of a successful civil servant approaching middle age.

But the stone remained in his locked drawer, and the dreams continued, growing more vivid and more specific as time went on. He would see technological developments before they were announced, would understand political shifts before they became obvious, would recognize patterns in human behavior that allowed him to predict outcomes with unsettling accuracy.

The influence was still teaching him, still pushing knowledge into his consciousness despite the distance and despite his attempts to resist its lessons. In 1985, 13 years after his visit to the Darington estate, Thomas received a letter with no return address and a postmark from a small town in Eastern Kentucky.

Inside was a single sheet of paper covered in handwriting he recognized immediately as patients Daringtons, though the style had changed, become more mechanical, less fluid, suggesting the progression of changes she’d warned him about. The letter was brief and devastating in its implications. “The influence is accelerating,” she’d written.

“The reach has extended to nearly four miles now, and the transformations are occurring faster with each generation.” Hope, whom you met as an infant, can now predict individual human actions with 97% accuracy, despite being only 13 years old. The elders believe we have perhaps two more generations before the accumulated changes make human breeding impossible, before we transform into something so far removed from our origins that we can no longer produce viable offspring.

When that happens, the Darington line will end, and with it, our ability to contain the influence. What happens then we cannot predict though the possibilities we can see are uniformly catastrophic. I’m writing to warn you because you deserve to know and because if the containment fails, your world will need whatever preparation it can manage. Watch for signs.

Watch for impossible knowledge appearing in unexpected places. Watch for people whose eyes are wrong and whose understanding exceeds what their education should permit. When you see these things, you’ll know the influence has escaped, and you’ll know the time remaining is measured in years rather than decades.

Thomas had burned the letter immediately after reading it, destroyed the evidence as thoroughly as he could, but the words remained seared into his memory. He’d started paying more attention after that, started noticing things he’d previously dismissed as coincidence or exceptional intelligence. A physicist who published papers describing phenomena he couldn’t possibly have observed with available technology.

A child prodigy whose understanding of complex mathematics far exceeded even gifted education. A politician whose predictions about international events were consistently impossibly accurate. Were these isolated cases of natural genius or were they something else? Were they early signs that the influence had found other vectors, other ways to spread beyond the Darington estate? Thomas couldn’t know for certain, couldn’t investigate without drawing attention to knowledge he’d sworn to keep secret, so he simply watched and worried, and felt the weight

of his burden growing heavier with each passing year. His own children were normal, thankfully. No signs of enhanced awareness or physical changes, just ordinary kids growing into ordinary adults with all the beautiful messiness that implied, but Thomas found himself studying them sometimes, watching for any suggestion of the wrongness he’d seen in Baby Hope, any indication that proximity to the stone in his drawer had somehow contaminated his bloodline.

He never told his wife about the Darington estate, never explained the locked drawer or the occasional nightmares that left him gasping and sweat soaked in the darkness. She’d asked early in their marriage about the scars on his psyche that manifested in those sleeping hours, but he’d deflected with vague references to difficult experiences during his surveying work, and eventually she’d stopped asking, accepting that there were parts of his past he couldn’t or wouldn’t share.

In 1990, Thomas’s daughter brought home a boyfriend, a young man studying computer science at the state university. Over dinner, the boyfriend had talked enthusiastically about his research into artificial intelligence and neural networks, describing concepts that Thomas recognized from the diagrams in patients’s journal.

The impossible knowledge he’d possessed despite never leaving the Darington estate. After the young man left, Thomas had sat alone in his study, staring at the locked drawer, wondering if the patterns were converging, if the future patients had seen was beginning to manifest. Was the boyfriend’s research independent discovery, or was it influenced somehow by knowledge that had leaked from the estate? The question was unanswerable, but it haunted Thomas for weeks afterward.

Made him realize that even if the Darington family succeeded in maintaining their physical isolation, the knowledge they possessed was beginning to emerge independently. The trajectory of human progress, reaching points that the influence had shown them decades or centuries earlier. The nightmares intensified as Thomas aged, became more specific and more disturbing.

He would dream of the Darington estate in flames, of clan members fleeing into the forest only to be hunted down by forces Thomas couldn’t clearly see, military perhaps, or corporate security or something else entirely. He would dream of the influence freed from containment, spreading like crystalline cancer through the bedrock, reaching toward population centers with tendrils of dark material that transformed everyone they touched.

He would dream of patients, now in her 40s or 50s, if she was still alive, no longer recognizable as the young woman he’d met, her body warped by accumulated changes, and her mind vast and cold and utterly inhuman. and he would dream of his own death, seeing with the same predictive clarity that the influence granted its victims exactly how and when his life would end, unable to change the pattern because knowing the future didn’t grant the power to alter it.

By 1995, Thomas was approaching retirement, counting down the months until he could leave the Department of Natural Resources and the constant fear that someone would discover the gap in his surveying records. Wood would ask questions about the Eastern Ridge that had been deemed worthless for development.

He had successfully buried the evidence of the Darington estate’s existence, had ensured that no map showed its location, that no record suggested anything unusual about that particular stretch of wilderness. But he knew the protection was temporary, that satellite imaging technology was improving every year, that eventually someone would notice the geometric patterns of the estates walls and gardens, would recognize signs of human habitation in an area that was supposed to be pristine forest.

When that happened, when the discovery became inevitable, what would he do? What could he do beyond hope that patients had been right about the consequences of exposure? That the people who found the estate would be wise enough to understand the danger and maintain the secret? The answer came in a way Thomas hadn’t anticipated, though perhaps he should have, given his growing ability to see patterns.

In late October 1995, he received another letter. This one not from patience, but from someone signing themselves simply as the Elder Council. The handwriting was archaic, formal, written in ink that looked like it had been made from charcoal and blood. Thomas Huitt, the letter began, your service to the containment has been noted and appreciated.

For 23 years, you have kept our secret despite the burden it imposed. For 23 years, you have resisted the temptation to share the knowledge, to seek validation for your impossible experience, to lighten your load by making it someone else’s responsibility. This restraint has been remarkable given your limited exposure to the influence, and it has confirmed patients Darington’s assessment of your character.

However, time remains a factor, and the patterns suggest that your natural death would occur before the next critical juncture in the estate’s history. This creates a complication, as your knowledge and your silence will be needed in the years to come.” The letter continued, and with each sentence Thomas felt a cold horror spreading through his chest.

“We extend to you an invitation,” the elder council had written. Return to the Darington estate. Accept fuller exposure to the influence. Join us not as clan member but as guardian, as watcher, as the bridge between our isolated world and the civilization beyond. The transformation would be gradual, would grant you decades of extended life and the enhanced perception necessary to predict and prevent discovery.

you would become like us, no longer fully human, but serving a purpose greater than any individual life. The alternative is to live out your remaining years with the knowledge you possess, to die with the burden unshared, to trust that others will maintain the containment in your absence. The choice is yours, Thomas Huitt, but we ask that you choose wisely, with full understanding of what is at stake.

Thomas had torn the letter into tiny pieces and flushed them down the toilet, destroying the evidence with shaking hands and a heart that hammered against his ribs like it was trying to escape his chest. The invitation was obscene, a perversion of everything he’d tried to preserve by maintaining his distance from the Darington estate.

To return, to willingly accept transformation into something past human, to sacrifice whatever remained of his ordinary life for the sake of containment. It was too much, asked too much, demanded a commitment that went beyond anything he’d agreed to when patients had let him leave in 1972. And yet, even as he rejected the idea intellectually, some part of him, the part that held the stone late at night, the part that dreamed in patterns and possibilities, understood the logic of their request, saw the trajectory they

were proposing, and recognized it as optimal for maintaining the secret. He didn’t respond to the letter, didn’t acknowledge that he’d received it, tried to continue his life as though the invitation had never been extended. But the dreams changed after that, became more insistent, more specific, showing him futures where his refusal led to discovery and catastrophe, where his acceptance led to successful containment, but personal annihilation.

The influence was showing him the consequences of both choices, was making clear that there was no path forward that didn’t involve sacrifice, either of the containment or of himself. Sleep became increasingly difficult, and Thomas found himself spending more and more time in his study, holding the wrapped stone, and trying to understand what was being asked of him, what duty he owed to a promise made decades ago to people who were no longer entirely human.

The decision was made for him in early 1996 when Thomas suffered what his doctors called a minor heart attack, but what he recognized as something else entirely, a message from his own body, transformed slowly over decades by proximity to even a small piece of the influence, telling him that his time was limited regardless of what choice he made.

He was 68 years old, older than Jeremiah Darington had been when he died trying to contain something beyond his understanding. And Thomas realized that he’d been granted more years than the patriarch, more time to live something approaching a normal life. The Elder Council’s invitation suddenly seemed less like a demand and more like an offer of reprieve, a chance to extend his existence long enough to see the containment through to whatever conclusion the patent suggested.

He told his wife he needed to take a trip, needed to visit some old surveying sites for closure before his retirement became official. She’d accepted the explanation with the tired patience of someone who’d long ago stopped expecting full honesty about the parts of his work he couldn’t discuss.

He’d packed a small bag, retrieved the stone from his locked drawer, and driven east into Kentucky, following roads that became progressively smaller and less maintained until he was on dirt tracks that barely qualified as paths. The forest closed in around him, and he felt that same oppressive silence he’d experienced 24 years earlier.

That sense of being watched by something vast and patient and utterly inhuman, the boundary was where he remembered it, though the wall had weathered further, more stones displaced by tree roots, more gaps where time and nature had worked to reclaim what humans had built. But it was still intact enough to serve its purpose, still clearly marking the transition from ordinary wilderness to something else entirely.

Thomas left his vehicle at the treeine and walked toward the gate, carrying nothing but the wrapped stone, and a certainty that he was crossing a threshold from which there would be no return. The gate was open, as though they’d been expecting him, and perhaps they had the influence granted. prediction after all, and they would have seen the pattern of his arrival long before he’d made the decision himself.

Patience was waiting in the courtyard, and Thomas barely recognized her. She was 50 now, though her body looked decades older, bent and twisted by the accumulated changes that had accelerated in the years since his first visit. But her eyes, those pale gray eyes that had seemed merely unusual in her youth, were now enormous, bulging from a skull that had reshaped itself to accommodate the enhanced perception they provided.

She smiled when she saw him, and the expression was wrong, too wide, showing too many teeth, but there was genuine warmth behind it nonetheless. “You came,” she said, and her voice was different, too. harmonics in it that suggested she was speaking on frequencies humans shouldn’t be able to produce.

I saw the probability was high, but probability isn’t certainty, and I’m glad my prediction was accurate. She moved toward him with that same fluid grace that had characterized all the Darington movements, though now it was more pronounced, more obviously inhuman. Are you ready, Thomas Huitt? Ready to become what you must become to fulfill the purpose you accepted 24 years ago.

Thomas looked past her to the estate, seeing that it too had changed, had grown in ways that defied ordinary architecture. New structures built in patterns that hurt to look at directly. Geometry that suggested the influence was expressing itself through the clan’s construction as much as through their bodies.