The first thing I remember is the sound of scissors. Not in person—just the way it played in my head when Ruth said the words.

“I cut it off. It was for the best.”

For a few seconds, I didn’t understand. I thought maybe she was talking about trimming Zoe’s bangs, something small, something harmless. But when we walked into Ruth’s living room and I saw my daughter sitting in the playpen, her curls gone—just gone—it felt like the air had been punched out of my lungs.

Zoe turned her head when she saw me. The soft black curls that used to bounce when she giggled were hacked away, leaving jagged tufts sticking out unevenly around her ears. My heart stopped. I dropped my purse. She smiled at me, shyly, like she didn’t understand why I was staring.

“She looks so much neater now, doesn’t she?” Ruth said cheerfully, standing behind the couch. Her tone was bright, almost proud, as if she’d done something kind. “I thought she’d fit in better this way. All the girls match now.”

Match. That was the word she used.

I didn’t say anything at first. I just bent down, scooped Zoe up, and felt the back of her head, running my hands through the rough, uneven ends where her perfect curls had been. She flinched a little, not because it hurt, but because she could tell something was wrong.

I turned to Ruth. “You cut my daughter’s hair?” My voice came out low, almost quiet, but there was a sharpness in it I’d never heard before.

Ruth crossed her arms, unbothered. “It was out of control. You never managed it properly, and it made her look messy next to Olivia and Chloe. You’ll thank me when you see how tidy she looks in pictures now.”

I could feel the blood rushing to my ears. “You had no right.”

“Oh, don’t overreact,” she said, rolling her eyes like I was being dramatic. “Hair grows back. And it’s just hair.”

It wasn’t just hair. It was Zoe’s identity. Her curls were from me—my mother’s side, thick, black, and springy. Every time I brushed them, I remembered my own childhood, sitting on a stool while my mother detangled mine with gentle hands and warm oil. I had sworn I’d do the same for my daughter, make her love what made her different.

Now Ruth had taken that from her, like she’d taken everything else.

But that wasn’t where it started.

Ruth had been playing favorites from the beginning.

She had three granddaughters: Olivia, the six-year-old prodigy with straight blonde hair and a toothy grin that could melt steel; Chloe, the four-year-old shadow who copied Olivia’s every move; and Zoe, my two-year-old, who Ruth treated like she was invisible.

When Zoe was born, Ruth arrived three hours late to the hospital because Olivia had a dance recital that “couldn’t be missed.” She held Zoe for exactly two minutes, made one lukewarm comment about her being “healthy enough,” and then spent the rest of the visit showing everyone videos of Olivia twirling across a stage.

For Zoe’s first birthday, Ruth brought a pharmacy teddy bear that still had the clearance tag on it. That same month, for Olivia’s birthday, she rented a bounce house, hired a princess impersonator, and bragged about it for weeks.

Tom, my husband, always told me I was imagining it. “She just connects better with older kids,” he’d say, rubbing my shoulder. But even he couldn’t ignore the way Ruth would babysit Olivia and Chloe every weekend while refusing to watch Zoe for even an hour.

And then there was the hair.

Olivia and Chloe had the same silky blonde hair Ruth adored—“family hair,” she called it. Zoe had mine. Thick, dark curls that bounced wildly when she ran. Ruth never let it go.

“What a shame she didn’t get the family look,” she’d say. “You can’t do much with that kind of hair.”

She’d brush Olivia’s hair gently, calling it “silk,” while ignoring Zoe sitting nearby. At every family event, she’d braid and style the other girls’ hair into ribbons and ponytails while Zoe watched quietly, clutching a little bow she never got to wear.

I caught Ruth once, telling Olivia, “Zoe’s hair just isn’t pretty like yours.” Olivia giggled. She was too young to know what that meant, but Zoe wasn’t. She didn’t cry, but she touched her curls self-consciously the rest of the day.

That Easter, Ruth bought matching designer dresses for Olivia and Chloe—complete with hats, gloves, and patent leather shoes. For Zoe, she grabbed a clearance dress two sizes too big. “It’ll do,” she said.

During dinner, she took dozens of photos of the two blondes. When I asked her to include Zoe, she laughed and said, “Not with that wild hair, she’ll ruin the picture.”

That was when Tom finally noticed.

After dinner, his brother pulled him aside and said what everyone else was thinking: Ruth’s favoritism wasn’t just obvious—it was cruel. Tom promised he’d talk to her. I wanted to believe he would, but I knew how deep her control ran in that family.

Two weeks later, Ruth called and offered to babysit all three girls while Tom and I attended his company’s award ceremony. It was the first time she’d ever offered to watch Zoe. Tom’s sister and brother insisted it would be “good for her” to spend time with all the grandkids together, to “bond properly.”

I almost said no. Something inside me hesitated, but I didn’t want to be the difficult one again. I dressed Zoe in her favorite yellow dress, tied a bow in her curls, and told her she’d have fun with Grandma.

When we came back that night, Olivia and Chloe were twirling in Ruth’s living room, wearing her jewelry and pretending to be princesses. Zoe was in the playpen. Her curls were gone.

I don’t remember walking across the room. I just remember Ruth’s voice, calm and patronizing.

“She looks better this way. More like her cousins.”

Tom went red. “You did this without asking us? You cut a toddler’s hair?”

“She’s two,” Ruth snapped. “She doesn’t care. Besides, that wild hair made the other girls look bad in pictures. You should be grateful I fixed it. Maybe now she’ll fit in better.”

And then she said it. The sentence that made my stomach turn.

“If you’d given me a blonde granddaughter like everyone else, this wouldn’t have happened.”

Tom exploded. I’d never seen him shout like that before. But it didn’t matter. Ruth didn’t flinch. She just crossed her arms, her mouth curling into that same smirk she used whenever she thought she’d won.

I took Zoe home that night.

She fell asleep in my arms, her small hands still reaching for curls that weren’t there. The next morning, I found strands of her hair in the bag Ruth had packed her toys in. Long, black ringlets tangled together like a keepsake someone meant to keep.

I threw them away.

When I tried to brush what was left, Zoe whimpered. “It hurts,” she said, even though I wasn’t pulling.

At the salon, the stylist took one look and went pale. “Who did this?” she asked quietly.

“My mother-in-law,” I said.

She didn’t comment after that. Just knelt in front of Zoe, whispering, “We’ll make it pretty again, okay?”

The haircut she gave her was short, soft—a pixie cut that tried to make sense of the chaos. But nothing could replace those curls. When Zoe looked at herself in the mirror, she tilted her head, confused. “Where did my hair go, Mommy?”

I couldn’t answer.

I pulled the car over two blocks from the salon because I couldn’t stop crying. Zoe sat in the back seat, humming softly to herself, still smiling, still innocent, while I clutched the steering wheel and tried to breathe through the ache in my chest.

And that’s when I realized—it wasn’t just about hair. It was about everything Ruth had taken from us. The small, quiet cruelties that built up over years. The way she made my daughter feel like less.

I thought I could forgive her for a lot of things. But this?

This was the line she couldn’t cross and come back from.

And as I sat there in the car, staring at my daughter’s reflection in the rearview mirror, I knew one thing for sure: something in me had finally changed.

And Ruth wasn’t ready for what came next.

My mother-in-law, Ruth, had three granddaughters, but only loved two of them. Her favorite was Tom’s sister’s kid, Olivia, who was six and could do no wrong. Everything Olivia did was perfect and brilliant and deserved celebration.

Next was Tom’s brother’s daughter, Chloe, who was four and got the silver medal treatment with constant praise and expensive gifts. Then there was my daughter, Zoe, who was two and got treated like she didn’t exist. The favoritism started the day Zoe was born. Ruth showed up at the hospital 3 hours late because Olivia had a dance recital that couldn’t be missed.

When she finally arrived, she held Zoe for exactly 2 minutes, said she looked healthy enough, then spent the rest of the visit showing everyone videos of Olivia’s performance. For Zoe’s first birthday, Ruth brought a $10 stuffed animal from the pharmacy. For Olivia’s birthday the same month, she rented a bounce house and hired a princess impersonator.

The difference was so obvious that other family members started commenting, but Ruth would say Olivia was older and needed more elaborate parties. Tom always made excuses, saying his mom was just more comfortable with older kids, but I knew better. Ruth would babysit Olivia and Kloe every weekend, taking them shopping and to movies and restaurants.

When I asked if she could watch Zoe for 2 hours so I could go to a doctor’s appointment, she said she was too busy, but maybe I should try finding a real babysitter. She had professional photos taken of Olivia and Kloe every few months, but never once asked for pictures of Zoe. Her house was covered in framed photos of the other girls, but Zoe’s picture was stuck to the fridge with a magnet, half hidden behind a grocery list.

The hair situation made everything worse. Olivia and Kloe both had straight blonde hair like their moms. While Zoe had inherited my thick black curls. Ruth constantly compared them, saying, “It was such a shame Zoe didn’t get the family hair. She’d run her fingers through Olivia’s hair, calling it silk while barely looking at Zoe.

She bought expensive hair accessories for the other girls, but told me Zoe’s hair was too unruly for pretty things. At family gatherings, she’d style Olivia and Khloe’s hair into elaborate braids and ponytails while Zoe sat there watching. When Zoe would ask for a pretty hairstyle, too, Ruth would say her hair wasn’t the right type and she should just wear it down.

The breaking point came at Easter dinner when all three girls were there. Ruth had bought Olivia and Kloe matching Easter dresses with bonnets and shoes, spending at least $200 on each outfit. For Zoe, she grabbed a clearance rack dress that was two sizes too big, and said it would do. During dinner, she kept taking photos of Olivia and Kloe, calling them her beautiful princesses.

When I suggested taking a photo of all three granddaughters together, Ruth said Zoe’s wild hair would ruin the picture. She actually said that out loud in front of everyone. Tom finally started noticing how bad it was when his own brother pulled him aside and said Ruth’s favoritism was getting cruel. The next week, Tom and I had to attend his company’s award ceremony where he was getting a promotion.

Ruth offered to watch all three girls together for the first time ever. I was suspicious, but Tom’s sister and brother pushed for it, saying maybe Ruth needed time with all of them to bond properly. I left Zoe with her favorite dress and a bow for her hair, hoping Ruth might include her for once.

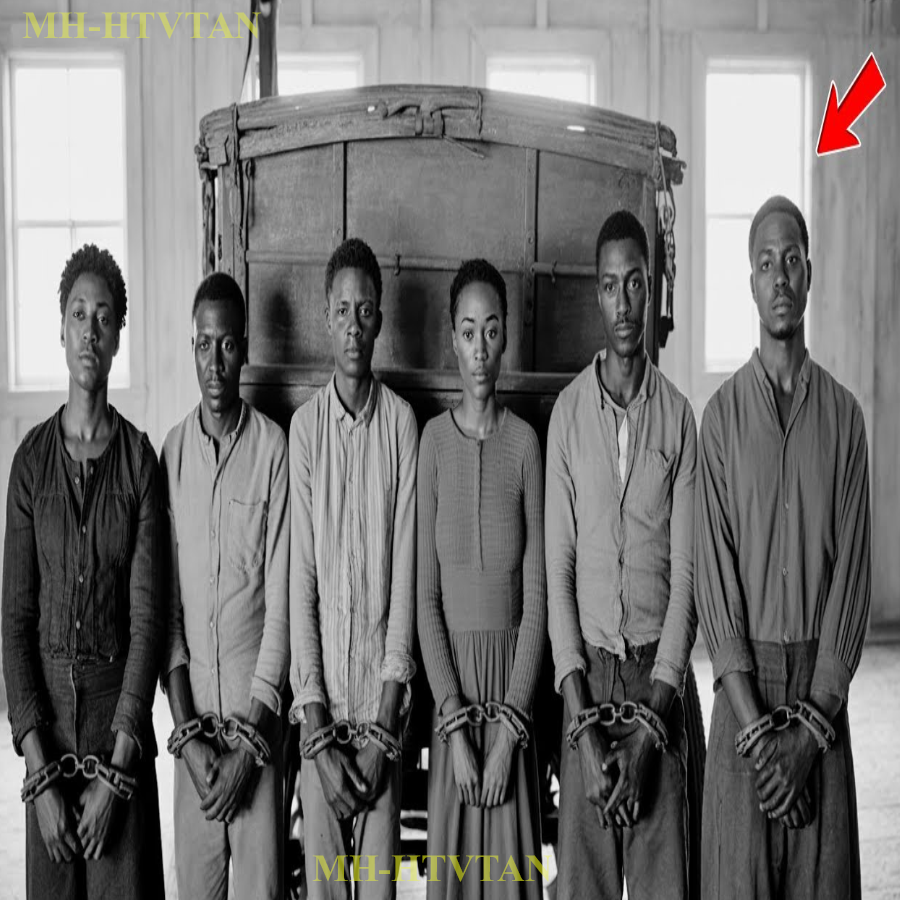

When we came back, Olivia and Kloe were playing dress up in Ruth’s jewelry while Zoe was sitting alone in the playpen with her beautiful curls completely gone. Ruth had cut my baby’s hair into this choppy disaster that barely covered her ears. It was so uneven and horrible that Zoe looked like she’d been attacked. Ruth’s explanation made my blood boil.

She said Zoe’s hair was making the other girls look bad in photos, and now all three granddaughters matched better. She literally destroyed my daughter’s hair because it didn’t look like her favorites. She said I should be grateful because now Zoe might fit in with the family better. Tom lost it completely, screaming at his mother about her blatant favoritism and cruelty.

Ruth just shrugged and said, “If we’d given her a blonde granddaughter like everyone else, this wouldn’t have happened. That comment broke something in me.” I took Zoe home and spent the night holding her while she kept touching her missing curls. The salon could only do so much to fix the hack job, and my beautiful girl looked so different.

Tom said we were done with his mother, but I had other plans. First, I created a social media account called Grandmas Who Play Favorites and started posting everything. Requested reads is on Spotify now. Check out link in the description or comments. I uploaded the $10 stuffed animal photo first, placing it next to screenshots from Ruth’s Facebook where she’d posted about Olivia’s bounce house party with the princess impersonator.

The difference was brutal. My fingers moved fast across the keyboard as I added the Easter dress comparison. The clearance rack disaster next to those matching $200 outfits Ruth bought for the other girls. Each post felt like releasing pressure from a wound that had been building for 2 years.

Within 20 minutes, three people commented with their own grandmother favoritism stories. Within 40 minutes, 12 more joined in. By the time an hour passed, my notifications wouldn’t stop buzzing with messages from strangers saying they’d lived through the same thing, that their parents or in-laws had picked favorite grandchildren and destroyed family relationships over it.

Tom sat on the couch beside me, watching the screen fill with comments and shares. He didn’t say anything about taking the post down or giving his mother another chance. His eyes kept moving toward Zoe’s bedroom door, where our baby slept with her butchered hair. and each time he looked, his jaw got tighter and his hands clenched harder against his knees.

I posted the hospital story next, how Ruth showed up 3 hours late because Olivia’s dance recital mattered more than meeting her newborn granddaughter. Someone commented asking if I was making it up because no grandmother could be that cruel, and I replied with the exact timestamps from that day.

The texts Ruth sent saying she’d come after the recital finished. The validation from internet strangers shouldn’t have mattered as much as it did. But after two years of Tom making excuses and family members staying silent, having people confirm that Ruth’s behavior was wrong, felt like breathing again. My phone started buzzing before sunrise with texts from extended family asking if the social media account was really mine.

Tom’s phone lit up with messages from his sister and brother, his cousins, even his aunt who lived two states away. By the time I checked the account at 6:00 in the morning, it had 300 followers, and my hair cutting post had been shared 40 times across different parenting groups and family drama forums. Camila called at 7 demanding to know why we were airing private family business for the whole world to see.

Her voice sharp with anger. Tom told her their mother cut off a toddler’s hair out of spite and asked what exactly should stay private about child abuse. Camila went quiet for a second before insisting it wasn’t abuse, just a bad decision. And couldn’t we handle this like adults instead of blasting Ruth online? Tom asked where this adult conversation was supposed to happen.

At the next family gathering where Ruth would ignore Zoe while fawning over Olivia and Kloe like always, Camila hung up without answering. I called the best children’s hair stylist in town and begged for an emergency appointment, explaining what happened in enough detail that she cleared her schedule for us. The stylist was a woman in her 50s with kind eyes who took one look at Zoe’s head, and her expression went cold.

She knelt down to Zoe’s level and asked if she could fix her hair to make it pretty again, and Zoe nodded while touching the choppy ends near her ears. The woman worked carefully with her scissors, trying to even out Ruth’s hack job into something that looked intentional instead of violent. She managed a pixie cut that was cute enough, but my baby’s beautiful black curls were gone and wouldn’t grow back for years.

Zoe kept reaching up to touch her head during the haircut. Her little fingers searching for the curls that used to bounce when she moved. When we got in the car to leave, she asked why grandma made her hair go away, and I had to pull over two blocks from the salon because I couldn’t see the road through my tears.

Tom called his mother from our kitchen while I made lunch for Zoe, his voice flat and cold in a way I’d never heard before. He told Ruth she wasn’t welcome in our home anymore and wouldn’t see Zoe until she could explain why destroying a toddler’s hair was acceptable behavior. Ruth’s voice came through the speaker phone loud enough for me to hear from across the room, crying about how we were being cruel to her, how she was just trying to help Zoe fit in better with her cousins.

Tom asked how cutting off a child’s hair without permission helped anything. And Ruth said through her tears that now all three girls could match in photos, that Zoe’s wild hair made the other girls look bad by comparison. The words hit me like a physical blow even though I’d heard them before.

Tom told his mother she was sick and hung up while she was still talking. I posted Ruth’s exact words about helping Zoe fit in better on the social media account, adding the before photos where all three girls stood together at Easter with their drastically different hair. The comment section exploded within minutes. People called out the racist undertones immediately, pointing out that Ruth clearly had a problem with Zoe’s dark features and curly hair, that this wasn’t about matching granddaughters, but about Ruth wanting Zoe to look white like the other girls.

Someone linked articles about hair discrimination and how attacking a child’s natural hair was a form of abuse that caused lasting psychological damage. Another person shared a story about their own grandmother who treated them differently because they didn’t look like the rest of the family and how 30 years later they still struggled with feeling unwanted.

The post got shared 200 times in 3 hours. Camila showed up at our house that afternoon without calling first, parking in our driveway and marching to the front door with her arms crossed. She started talking before I even fully opened the door, saying we were making Ruth look like a monster over a simple haircut. That family problems should stay private instead of being broadcast to strangers online.

Tom came up behind me and told his sister that their mother literally said she wished we’d given her a blonde granddaughter, that Ruth’s words, not ours. Camila’s face went pale and her arms dropped to her sides. She opened her mouth to argue, but nothing came out because she couldn’t deny that sounded exactly like something Ruth would say.

Tom asked if she remembered all the times Ruth compared the girl’s hair. called Zoe’s curls unruly and wild while praising Olivia’s straight blonde hair as silk. Camila looked at the floor and said she thought their mom was just being old-fashioned. But Tom said no, she was being racist and playing favorites, and they’d all ignored it long enough.

The therapist’s office had gentle lighting and toys scattered across a soft rug, the kind of space designed to make children feel safe. The therapist was younger than I expected, maybe early 30s, with a calm way of moving that put Zoe at ease within minutes. She played with Zoe using dolls and drawing while asking careful questions about family and feelings.

After 30 minutes, she asked to speak with Tom and me privately while Zoe played in the waiting room with a supervised aid. The therapist was gentle but direct, explaining that the hair cutting combined with years of different treatment had already affected Zoe’s self-image at just 2 years old. She said Zoe showed signs of understanding that she was less favored than her cousins, that she’d internalized the message that something about her wasn’t good enough.

The therapist recommended weekly sessions and absolutely no contact with Ruth until Zoe was much older and could process the rejection properly with professional support. She said forcing contact now would only reinforce Zoe’s belief that she had to accept being treated as less than. I posted about the therapy recommendation that night without naming the professional or giving details that could identify her.

I explained that my toddler was now in therapy because her grandmother’s favoritism had damaged her sense of selfworth before she was even old enough for preschool. The account had grown to over a thousand followers, and my post got picked up by three different local parenting groups who shared it with warnings about grandparent favoritism.

Comments flooded in from people sharing their own therapy stories. Adults who were still working through childhood rejection from grandparents who played favorites. Someone started a thread listing signs of favoritism to watch for, and someone else created a resource document with therapist recommendations and articles about protecting children from toxic family members.

Ruth’s Facebook went dark within 48 hours of my first post. Her friends started commenting on her older posts asking about the allegations, wondering if the stories about her cutting a granddaughter’s hair were true. Ruth deleted every comment and then deleted her entire social media presence, removing years of photos and posts in one sweep.

Tom’s brother, Hank, called on the third day, saying their mother was devastated and humiliated, asking, “Couldn’t we please take down the posts and handle this privately like adults?” I told Hank that Ruth had years to handle this privately, while she showered his daughter with love and treated mine like an inconvenience. And now everyone got to see exactly what kind of grandmother she really was.

Hank hung up on me, but I noticed he didn’t actually defend his mother’s behavior. The silence on his end before the click said more than any argument could have. I set my phone down and stared at it for a minute, waiting to see if he’d call back with some excuse about Ruth meaning well or being from a different generation. The phone stayed dark.

Tom looked over from where he was cleaning up Zoe’s dinner dishes and raised his eyebrows in question. I shook my head and he nodded, understanding passing between us without words. The next morning started the flood of messages from extended family. Tom’s aunt sent a long text saying she’d always noticed Ruth treated the girls differently, but thought it wasn’t her place to interfere with how Ruth chose to spend time with her grandchildren.

Tom’s uncle called that afternoon, admitting he’d felt uncomfortable watching Ruth fawn over Olivia while barely acknowledging Zoe at family gatherings. His wife sent a separate message saying she’d mentioned it to Ruth once years ago and got such a cold response that she never brought it up again.

Each message followed the same pattern of confession and excuse. They saw it. They knew it was wrong, but they convinced themselves it wasn’t their business or that speaking up would just cause family drama. By the end of the second day, seven different relatives had reached out with variations of the same apology. Part of me felt good having my observations validated after Tom spent so long telling me I was being too sensitive about his mother’s preferences.

These people had watched Ruth shower Olivia with attention and gifts while treating Zoe like an afterthought. And now they were finally admitting they saw exactly what I saw. But the anger burned hotter than any satisfaction. Where were these people when Zoe sat alone at birthday parties while Ruth braided Olivia’s hair? Where were they when Ruth brought expensive presents for two granddaughters and pharmacy toys for the third? They watched my baby get rejected over and over and said nothing because keeping peace was more important than protecting a child.

I responded to each message with the same basic reply. Thank you for reaching out, but validation now doesn’t undo 2 years of Zoe learning she wasn’t good enough for her own grandmother while your entire family watched it happen. 3 days after Hank hung up on me, Camila called. Her voice sounded different this time, quieter and less defensive than when she’d shown up at our house angry about the social media posts.

She asked if I had a few minutes to talk and I almost said no. But something in her tone made me stay on the line. Camila started by saying she’d been doing a lot of thinking since seeing the posts and talking to Tom. She admitted she knew her mother treated Olivia better than the other girls, but had convinced herself it was because Olivia was the oldest and needed more attention.

She said she told herself that Zoe would get the same treatment when she was older, that Ruth was just more comfortable with six-year-olds than toddlers. I listened without interrupting, letting her work through her confession. Then Camila said something that surprised me. She apologized for not speaking up sooner and said she’d been thinking about all the times she accepted expensive gifts for her daughter while Zoe got nothing.

She mentioned the Easter dresses specifically, remembering how she’d thanked Ruth for the $200 outfit while watching me try to adjust the clearance dress that was too big for Zoe. Camila said she felt sick thinking about how many times she’d let that kind of thing happen without questioning why Ruth treated the girl so differently.

Her voice cracked when she talked about the hair cutting, saying she couldn’t stop imagining how scared Zoe must have been sitting there while Ruth destroyed her curls. She asked if there was anything she could do now to help make things right. I told her the truth. Recognizing the problem now doesn’t erase the damage, and Zoe would be dealing with this rejection for years, according to her therapist.

But I also said that speaking up going forward would matter. that if Camila really wanted to help, she could start refusing Ruth’s favoritism toward Olivia and insisting all three girls be treated the same. That conversation gave me the idea for my next social media post. I sat down that night after Zoe went to bed and wrote about silent witnesses, about family members who watched favoritism happen and convinced themselves it’s not their place to intervene.

I wrote about how every adult who stayed quiet while Ruth were excluded. Zoe taught my daughter that her mistreatment was acceptable and normal. I explained that calling out favoritism isn’t causing drama. It’s protecting children from emotional abuse that will affect them for life. The post went up around 10 at night and by morning it had 200 comments.

Person after person shared stories about being the unfavored grandchild while aunts and uncles and cousins watched and said nothing. Someone wrote about how their grandmother openly preferred their brother and the whole family just acted like that was normal until the poster cut contact as an adult. Another person described watching their own child be excluded by grandparents while their siblings kids got special treatment and how hard it was to finally speak up after years of keeping quiet.

The comment section turned into this massive support group of people who’d experienced or witnessed favoritism. All agreeing that silence from other family members made the rejection so much worse. 2 days later, Tom came home from work looking tense. He said his father had called, which was unusual since his parents divorced 10 years ago and rarely communicated except about major family events.

Ruth had apparently reached out to her ex-husband, asking him to intervene on her behalf. Tom’s father wanted to talk to him about giving Ruth a chance to apologize properly. Tom asked his dad what Ruth had said about the situation, and his father admitted Ruth told him we were overreacting to a simple haircut and turning the family against her over nothing.

Tom asked if Ruth had mentioned the years of favoritism or the fact that she’d said she wished we’d given her a blonde granddaughter. His father went quiet for a minute, then said Ruth had left those parts out of her version. Tom told his dad the whole story, including Ruth’s comment about Zoe’s hair making the other girls look bad in photos.

His father listened and then said he believed Ruth was genuinely sorry and wanted to make things right. Tom asked the critical question. Did Ruth understand why what she did was wrong, or was she just sorry about the consequences? His father hesitated too long before admitting that Ruth still seemed to think we were blowing things out of proportion.

That answer told us everything we needed to know about whether Ruth had actually changed her thinking. Two weeks after the haircut cutting incident, Zoe started having nightmares. She’d wake up crying in the middle of the night, and when I’d go to comfort her, she’d ask why grandma didn’t like her hair. During the day, she started getting anxious whenever we mentioned family events or gatherings.

We had a birthday party invitation for Tom’s cousin, and when I told Zoe we were going to see family. She immediately asked if Grandma Ruth would be there. When I said no, she visibly relaxed. I called Zoe’s therapist and described the new behaviors. The therapist asked me to bring Zoe in for an extra session that week.

After working with Zoe using dolls and drawing, the therapist explained this was a normal trauma response for a child who’d experienced repeated rejection. She said Zoe had connected family gatherings with feeling excluded and hurt, and now her brain was trying to protect her by creating anxiety around those situations.

The nightmares were Zoe’s mind processing the fear and confusion of having someone she trusted hurt her. The therapist recommended continuing weekly sessions and maintaining the boundary of no contact with Ruth. She said forcing Zoe to see her grandmother right now would only reinforce the message that Zoe had to accept being treated badly by family members.

I posted about the nightmares that evening, careful not to include details that would identify Zoe’s therapist or reveal too much about the therapy process. I explained that my 2-year-old was having nightmares about her grandmother and getting anxious about family events because she’d learned that family gatherings meant watching other kids get love while she got ignored.

The response was immediate and intense. Comments flooded in within the first hour. people expressing anger that a grandmother’s favoritism had traumatized a toddler badly enough to cause nightmares. Several followers shared the post to their own pages, adding commentary about how grandparent favoritism was a form of child abuse that people didn’t take seriously enough.

By the next morning, the account had jumped from 1,000 followers to 5,000. Local parenting bloggers started reaching out through direct messages asking if they could cover the story. A few small news sites that focused on family issues sent requests for interviews. The attention was bigger than I’d expected when I first created the account, but it felt right that people were finally taking this seriously.

Tom and I talked about the interview requests over coffee while Zoe played in the next room. Part of me wanted to do a formal interview and really blast Ruth’s behavior into the public eye, but Tom worried that too much media attention might backfire and make us look like we were just trying to hurt his mother rather than protect our daughter.

We decided against the formal interviews, but I did write a detailed post explaining the complete history of Ruth’s favoritism. I included specific examples with dates, like Ruth showing up three hours late to the hospital when Zoe was born because of Olivia’s dance recital. I wrote about the $10 pharmacy stuffed animal for Zoe’s first birthday versus the bounce house and princess impersonator for Olivia’s party the same month.

I listed every time Ruth had refused to babysit Zoe while taking Olivia and Kloe every weekend. I described Ruth’s house covered in professional photos of two granddaughters while Zoe’s picture was hidden behind a grocery list on the fridge. I explained the hair comments, the expensive accessories for the other girls, the Easter dresses, and I ended with Ruth’s own words about wishing we’d given her a blonde granddaughter, and her explanation that Zoe’s hair made the other girls look bad in photos.

The post was long and detailed, and I hit publish before I could second guess myself. Within hours, it had been shared across multiple local parenting groups and community pages. People I’d never met were commenting that they’d seen Ruth around town and always thought she seemed like such a nice grandmother. Others said they’d witnessed some of these incidents at family gatherings or community events and hadn’t realized how bad the full pattern was.

The post went viral within our local community, spreading through neighborhood groups and school parent organizations. People started recognizing Ruth at the grocery store and the pharmacy. Hank called Tom 2 days after that detailed post went up. He was mad, his voice loud enough that I could hear him from across the room, even though Tom didn’t have him on speaker.

Someone had confronted Ruth at the pharmacy, asking her directly if she was the grandmother who’d cut off her granddaughter’s hair out of favoritism. Ruth had apparently broken down crying right there in the pharmacy aisle and come home so upset she couldn’t stop shaking. Hank wanted to know how he could be okay with strangers harassing his mother in public over family business.

Tom let his brother rant for a minute before responding in this calm, cold voice that I’d never heard him use before. He told Hank that public shame was a natural consequence of Ruth’s actions. He said maybe their mother should have thought about her reputation in the community before she cut off a toddler’s hair because it didn’t match her favorite granddaughters.

He pointed out that Ruth had spent two years publicly favoring Olivia and Kloe at family events and gatherings where other people could see, so she’d already made her behavior public long before I posted about it. Hank tried to argue that what happened in the family should stay in the family. And Tom asked him when exactly the family had planned to address Ruth’s treatment of Zoe if we’d kept quiet.

Hank didn’t have an answer for that. Camila reached out the next day asking if we could meet for coffee without the kids. I almost said no because I was tired of family members wanting to process their feelings about Ruth’s behavior while my daughter was in therapy dealing with the actual damage. But Camila had been the only one to really apologize.

So, I agreed to meet her at a coffee shop near my house. She was already there when I arrived, sitting at a corner table looking like she hadn’t slept well. When I sat down, she started crying before I could even order my coffee. She talked about all the times she’d accepted her mother’s favoritism as normal. How she’d felt proud that Olivia was Ruth’s favorite and never questioned why that meant Zoe had to be excluded.

She admitted she’d felt superior having the favorite grandchild, like it meant she was doing something right as a parent that Tom and I weren’t. She said she’d convinced herself that Ruth’s constant praise and expensive gifts for Olivia were just because they had a special bond, not because Ruth had a problem with Zoe’s appearance.

Camila cried harder when she talked about the hair, saying she kept thinking about how Zoe must have felt sitting there watching Ruth cut away her curls. She said she’d been looking back through photos from family events and could see Zoe’s face in the background of pictures, always watching Olivia and Kloe get attention while she sat alone.

She asked me how she could have missed something so obvious for so long. I appreciated that she was being honest, but told her that seeing the problem now didn’t fix the two years Zoe spent watching Olivia get everything while she got nothing. Camila nodded and wiped her eyes with a napkin that was already soaked through.

She said she wanted to make changes in how she handled Ruth’s gifts and attention toward Olivia, but didn’t know where to start. Tom had joined us by then because I’d texted him to come, and he suggested Camila could start by turning down Ruth’s excessive gifts and experiences for Olivia, or at least insisting that Ruth include all three granddaughters equally.

Camila looked down at her coffee cup and admitted this felt hard because Olivia had gotten used to being spoiled by Ruth. She said Olivia expected special treatment now and would be upset if the shopping trips and expensive presents stopped. Tom pointed out that was exactly the problem. that Ruth had taught Olivia to expect favoritism and now it was affecting how she treated her cousins.

Camila agreed it was necessary even though she didn’t know how to explain it to a six-year-old. The next day, I got a message through the Grandmas Who Play Favorites account from someone who said she was a family therapist specializing in favoritism dynamics. She offered to do a phone consultation with me for free because my post had resonated with her professional experience.

We set up a call for that afternoon and she explained that grandparent favoritism often came from prejudice about appearance, personality, or circumstances. She said it rarely changed without serious intervention because the grandparent usually didn’t see their preference as a problem. I asked if there was any hope for Ruth to change, and the therapist was honest that most grandparents who showed this level of favoritism didn’t develop genuine insight.

She explained they might modify their behavior when forced to, but the underlying preference usually remained. they just got better at hiding it or found more subtle ways to show favoritism. The conversation lasted almost an hour and she gave me specific examples of patterns she’d seen in other families. I shared the therapist’s insights on the social media account without identifying her and hundreds of people commented saying this matched their experience with favoritist grandparents.

Many adult children shared that they eventually cut off contact entirely because the dynamic never truly improved. One woman wrote that her mother still favored her brother’s kids 20 years later and had missed her daughter’s wedding because it conflicted with her favorite grandchild’s soccer game. Another person shared that their father had left money to only two of his five grandchildren in his will because those were the ones who looked like him.

The comments kept coming for days, and each one made me more certain that protecting Zoe from Ruth was the right choice. 3 weeks after the hair incident, a thick envelope arrived at our house with Ruth’s return address. Tom brought it inside looking like he wanted to throw it away without opening it, but I took it from him.

The letter was three pages long, written in Ruth’s careful handwriting. Most of it focused on how hurt she was by the social media posts and how we’d ruined her reputation in the community. She wrote about people whispering about her at church and her book club friends asking uncomfortable questions.

She said she couldn’t go to the grocery store without feeling like everyone was staring and judging her. The letter included one paragraph about regretting the haircut buried in the middle of page two. She wrote that she wished she’d asked permission first, but never actually apologized for the years of favoritism or acknowledged that she’d treated Zoe as less important than her other granddaughters.

Tom read it over my shoulder and then took it from my hands and threw it in the trash. He said his mother still didn’t understand what she did wrong because the letter was all about Ruth’s feelings and her hurt reputation. I fished the letter out of the trash and took a photo of it with my phone, blurring out any identifying details like her address and phone number.

I posted the photo on the account and the comment section filled with people analyzing how it was a classic non-apology that centered Ruth’s feelings rather than addressing the harm to Zoe. Several people shared similar letters they’d received from toxic family members that followed the exact same pattern. One commenter pointed out that Ruth had written three pages about her own pain, but only three sentences about what she’d done to Zoe.

Another person noted that Ruth never once used the word sorry or apologized for anything except not asking permission, which wasn’t even the real problem. Two days after I posted the letter, Marissa reached out to me directly for the first time through a private message. She admitted she’d always felt uncomfortable with how Ruth treated Zoe, but hadn’t spoken up because she didn’t want to rock the boat.

She apologized and asked what she could do now to help repair the damage. I told her the most helpful thing would be for her and Hank to stop accepting Ruth’s favoritism toward Kloe and to back us up when we maintained boundaries. Marissa agreed and said she’d been talking to Hank about how they’d enabled his mother’s behavior by accepting the expensive gifts and special treatment for their daughter while Zoe got nothing.

A month after the incident, Zoe’s therapist reports some progress, but notes that Zoe still shows anxiety around the topic of grandparents and asks repeatedly why Grandma Ruth doesn’t love her like she loves Olivia and Chloe. These questions break my heart every single time. I sit in the parking lot after the appointment and cry because my baby shouldn’t have to ask those questions at 2 years old.

She should just know she’s loved by everyone. The therapist explains that Zoe’s brain is trying to make sense of the rejection and that she’ll probably keep asking for a while. She recommends I give simple, age appropriate answers that validate Zoe’s feelings without badmouthing Ruth. I practice the responses on the drive home, but they all feel wrong because the truth is Ruth doesn’t love Zoe the same way, and I don’t know how to make that okay.

I share Zoe’s questions on the social media account, and the response is overwhelming. Hundreds of people share their own childhood memories of asking similar questions about why grandparents loved their siblings or cousins more, and many say they still carry that rejection decades later. One person writes about being 45 years old and still feeling the sting of watching their grandmother hug their sister while barely acknowledging them.

Another shares that they went to therapy as an adult specifically to process the damage from a favorist grandmother. The comments keep coming for days, and each one validates what I already know, that this kind of treatment leaves permanent scars. Several people thank me for protecting Zoe now instead of forcing her to keep accepting Ruth’s cruelty for the sake of family peace.

They say they wish their parents had done the same. Tom’s aunt reaches out saying she wants to organize a family meeting to address Ruth’s behavior, but Tom and I refuse to participate unless Ruth first acknowledges the full extent of her favoritism in writing. We’re done with family meetings where everyone pressures us to forgive and move on.

Tom’s aunt sounds frustrated when he explains our position, but he holds firm. He tells her that his mother needs to demonstrate real understanding before we’ll sit in a room with her. His aunt argues that Ruth is too proud to write something like that and maybe we could compromise by having a mediator present.

Tom says no compromise. Ruth writes it or we don’t come. His aunt hangs up saying we’re being unreasonable, but Tom just shrugs. He’s learned that protecting Zoe matters more than keeping his extended family comfortable. Ruth apparently hears about our conditions for a family meeting and sends another letter.

This one’s slightly better, but still focused mostly on her intentions rather than her impact. She claims she never meant to hurt Zoe and loves all her granddaughters equally, which is such an obvious lie that Tom doesn’t even finish reading it. He gets to the part where she says she loves them equally, and throws the letter across the kitchen.

I pick it up and read the rest where Ruth explains that she just has different relationships with each girl based on their personalities. She writes that Olivia is easier to connect with because she’s older and Khloe is more affectionate. She never once mentions that the real difference is their blonde hair and how they look like the family she wanted.

The letter ends with Ruth asking when she can see Zoe again because she misses her granddaughter. Tom takes the letter and writes across the top in red marker that Ruth is still lying and sends it back to her. 5 weeks after the haircut, the social media account has 10,000 followers and I’m getting messages daily from people thanking me for speaking up about grandparent favoritism.

Several people say the account helped them recognize similar dynamics in their own families and set better boundaries. One mother writes that she finally told her mother-in-law she couldn’t babysit anymore after seeing my posts because she realized the preferential treatment was damaging her younger son. Another person shares that they cut off contact with their father completely after reading about Zoe because they recognized the same pattern with their own kids.

The messages make me feel less alone but also sad that so many families deal with this poison. I start a discussion thread asking people how they handled favorist grandparents and the responses fill up with practical advice and warnings about what doesn’t work. Camila takes a major step by telling Ruth that she won’t accept any more expensive gifts or special experiences for Olivia unless Ruth provides exactly the same for all three granddaughters.

Ruth apparently cries and says Camila is punishing her, but Camila holds firm. She calls me afterward to tell me about the conversation and her voice shakes when she describes Ruth’s reaction. Ruth accused her of being ungrateful and said she was just trying to be a good grandmother to Olivia.

Camila told her that being a good grandmother means treating all the grandchildren fairly and Ruth started crying harder. Camila says she almost gave in, but then thought about Zoe sitting alone in that play pen with her butchered hair and stayed strong. Ruth ended the call by saying Camila was breaking her heart. Camila tells me she feels guilty, but knows it’s the right thing to do.

Hank and Marissa follow Camila’s lead and establish the same boundary with Ruth regarding Kloe. Ruth calls Tom crying about how her own children are ganging up on her, and Tom tells her that they’re finally holding her accountable for treating their children differently. I can hear Ruth’s voice through the phone, even though Tom doesn’t have it on speaker.

She’s wailing about how nobody understands her and everyone is being cruel. Tom stays calm and tells her that she created this situation by favoring two granddaughters over the third. Ruth screams that she never did any such thing and Tom hangs up on her. He sits on the couch afterward looking exhausted and says he never thought his siblings would actually back us up.

I tell him they’re doing it for their kids as much as for Zoe because Ruth’s favoritism was teaching all three girls terrible lessons. 6 weeks after the incident, Ruth asks through Tom’s aunt if she can see Zoe for a supervised visit with us present. Tom and I discuss it with Zoe’s therapist, who says it’s too soon, and that Zoe needs more time to heal before facing her grandmother again.

The therapist explains that Zoe is just starting to feel secure and safe, and seeing Ruth could undo that progress. She recommends waiting at least another month and then reassessing based on Zoe’s continued therapy work. Tom calls his aunt back and relays the therapist’s recommendation. His aunt size and says Ruth is going to be devastated, but she understands.

She asks if there’s anything Ruth can do to speed up the process, and Tom says no. Zoe’s healing happens on Zoe’s timeline, not Ruth’s. I post about Ruth’s request for contact and the therapist’s recommendation to wait, and the comments overwhelmingly support protecting Zoe’s healing process over Ruth’s desire for access.

Many people share that they wish their parents had protected them from favoritist grandparents instead of forcing contact. One person writes about being made to hug a grandmother who openly preferred their brother and how violated that made them feel. Another shares that their parents kept pushing reconciliation until they were old enough to refuse contact themselves.

The validation from strangers helps when Tom’s extended family starts texting asking if we’re being too harsh. I screenshot some of the comments and send them to the family group chat without additional comment. Two months after the haircut, we attend a family birthday party for Tom’s cousin with Zoey, but Ruth is not invited per our request.

Several family members comment on how much happier and more confident Zoe seems without Ruth’s presence creating anxiety. Tom’s uncle pulls me aside and says Zoe is like a different kid playing with the other children and laughing instead of clinging to my leg. He admits he didn’t realize how much Ruth’s treatment was affecting her until he saw the difference.

Zoe runs around the backyard with her cousins and asks me twice if Grandma Ruth is coming. When I tell her no, she visibly relaxes and goes back to playing. Tom watches her and his eyes get wet. He says our daughter shouldn’t feel relief about a grandmother not being at a party. Camila catches me by the punch bowl and leans in close, her voice dropping low.

She tells me Olivia has been asking why Grandma Ruth doesn’t take her shopping anymore. Camila had to explain that grandma made some mistakes and needs to treat all the cousins fairly. Olivia apparently said that didn’t seem fair since she’s the oldest. The comment makes my stomach drop because it shows how deeply Ruth’s favoritism has affected Olivia, too.

Camila looks embarrassed sharing this, but says she thought I should know. I thank her for being honest and tell her it’s not her fault that Ruth taught Olivia to expect preferential treatment. The conversation stays with me for the rest of the party. I watch Olivia playing with Zoe and Khloe, and I can see how she naturally takes charge, how she expects the other girls to follow her lead.

Ruth didn’t just hurt Zoe by excluding her. She also damaged Olivia by teaching her that being blonde and older made her more deserving of love and attention. She taught Khloe that she was second best no matter what she did. The whole dynamic was poisoning all three girls in different ways. This insight makes me even more determined to maintain our boundaries because fixing this isn’t just about protecting Zoe anymore.

It’s about breaking a cycle that was teaching all three cousins terrible lessons about worth and favoritism. Tom’s brother, Hank, pulls Tom aside near the end of the party, and I watch them talking seriously by the back fence. When Tom comes back, he tells me Hank admitted he feels guilty for not noticing sooner how extreme their mother’s favoritism was.

Hank said he’s been thinking about all the times Zoe was excluded while Kloe got special treatment, all the shopping trips and movie dates and expensive gifts. Tom says Hank kept apologizing and saying he should have spoken up years ago. His awareness comes late, but it feels genuine. Hank walks over to me before they leave and tells me directly that he’s sorry for not protecting Zoe when he saw what was happening.

He says he convinced himself it wasn’t as bad as it looked because that was easier than confronting his mother. I appreciate his honesty even though it doesn’t change the past. At least now both Tom’s siblings are finally seeing the damage Ruth caused and taking responsibility for their part in enabling it.

3 months after the incident, we have another therapy session with Zoe’s therapist. She reports significant improvement in Zoe’s anxiety and self-image. Zoe is sleeping better, playing more confidently with other kids, and asking fewer questions about why Grandma Ruth doesn’t love her. The therapist shows us drawings Zoe made during their sessions, and the recent ones show her with big curly hair and a smile, standing next to other kids instead of off to the side alone.

The progress makes me want to cry with relief, but the therapist also warns us that Zoe will likely need ongoing support as she gets older, and processes the rejection more fully. She explains that right now, Zoe is young enough that therapy can help reshape her understanding before the memories solidify into lasting trauma. As Zoe gets older and develops more complex thinking, she’ll need to work through what happened at different developmental stages.

The therapist recommends maintaining the no contact boundary with Ruth for at least another 3 months to give Zoe more time to heal without the stress of seeing her grandmother. A week later, another letter arrives from Ruth. I almost throw it away without opening it, but Tom says we should at least see what she has to say this time.

This letter is different from the previous ones. Ruth actually acknowledges that she treated Zoe differently than Olivia and Kloe. She admits that she had prejudices about Zoe’s appearance that she didn’t recognize as wrong. She writes that seeing Olivia and Khloe’s blonde hair made her feel connected to them in a way she didn’t feel with Zoe and she never questioned why that was or whether it was fair.

The letter is better than her previous attempts, but it still doesn’t fully take responsibility for the emotional damage. She focuses a lot on her own confusion and hurt feelings about being cut off from the family. She asks if there’s anything she can do to make things right, but doesn’t actually suggest any concrete actions or changes.

Tom reads it twice and says it shows some progress, but he’s not convinced his mother truly understands what she did. We take the letter to Zoe’s therapist at our next appointment. She reads it carefully and says it shows some progress in Ruth’s awareness. Ruth is at least acknowledging the differential treatment and admitting to prejudice, which is more than many grandparents in similar situations ever manage.

But the therapist recommends waiting to see if Ruth’s behavior changes before allowing any contact. She warns us that many people can write good apologies but struggle to actually modify their behavior longterm. The real test will be whether Ruth can sustain this awareness and translate it into different actions, not just words on paper.

The therapist suggests we maintain the current boundaries for now and see if Ruth continues working on herself or if this letter was just an attempt to regain access to the family. Tom and I agree to keep waiting. I’m not ready to expose Zoe to Ruth again based on one better letter. I post a general update on the Grandmas who play favorites account, explaining that we’re maintaining boundaries while the person involved does work to address their favoritism.

I don’t share specific details about Ruth’s letter, but I talk about the importance of watching for changed behavior rather than just accepting apologies. The post gets hundreds of comments within hours. People share their own experiences with family members who apologized beautifully, but then went right back to the same harmful patterns.

Others talk about the pressure they faced to forgive and reconnect before the person had actually changed. Several commenters thank me for prioritizing my daughter’s well-being over family pressure to keep the peace. One woman writes that she wishes her parents had protected her this way instead of forcing her to keep seeing a grandmother who favored her brother.

Reading these comments reminds me why I started the account in the first place. Four months after the hair cutting, Tom gets a call from his aunt saying the family held a meeting without us present. She tells Tom they confronted Ruth about her pattern of favoritism and the damage it caused to all three granddaughters.

According to his aunt, Ruth finally broke down and admitted she was wrong. She cried and said she never meant to hurt anyone, but she realizes now that her actions did cause harm. Tom’s aunt sounds hopeful on the phone, like this breakthrough means everything can go back to normal soon. But then she mentions that Ruth is struggling to understand why her preference for blonde hair became such a problem.

She apparently kept asking why it mattered that she connected more easily with Olivia and Kloe, why she couldn’t just be closer to some grandchildren than others. Tom’s aunt tried to explain, but Ruth didn’t seem to fully grasp it. Tom thanks his aunt for the update, but tells her we’re not ready to reconnect yet.

The fact that Ruth still doesn’t fully grasp why favoring children based on appearance is harmful tells me she has a long way to go. Tom agrees when we talk about it that night. He says his mother might never completely understand because she’d have to confront some ugly truths about herself and her values. We decide to maintain the no contact boundary for now while Ruth works with her own therapist.

Tom says his aunt mentioned that the family is insisting Ruth get professional help, which is more than I expected from them. At least they’re not just sweeping this under the rug anymore. 2 weeks later, Camila calls with more news. She tells me Ruth has started therapy at the family’s insistence.

Her therapist is apparently working with her on understanding implicit bias and how her preferences hurt Zoe. Camila says Ruth has been going twice a week and actually doing the homework her therapist assigns. She’s been journaling about her feelings and reactions to the different granddaughters and trying to identify where her prejudices came from.

This is more progress than I expected, but I remain cautious about whether Ruth can truly change. Camila admits she’s skeptical, too, but says it’s at least something. I tell Camila I appreciate her keeping us updated and that we’ll consider contact again if Ruth shows sustained change over several more months.

For now, protecting Zoe has to come first. 5 months after the haircut, I held Zoe in front of the bathroom mirror while she touched the little spiral curls growing back around her ears. She kept giggling and pulling them straight to watch them bounce back into shape. The pixie cut had finally grown out enough that her natural texture was returning thick and beautiful, just like before Ruth destroyed it.

Zoe pointed at her reflection and said her hair was getting pretty again and I had to blink back tears because for months she’d been saying her hair was ugly. The therapist called this progress during our next session, explaining that Zoe was starting to reclaim her self-image after Ruth’s attack. She said children Zoe’s age formed their sense of beauty from how adults treat them, and the fact that Zoe could feel excited about her curls again meant she was healing from the message that her natural hair made her less worthy. I took a photo of Zoe’s

growing curls that afternoon, carefully angling it so her face stayed hidden, but the beautiful spirals showed clearly against my hand. I posted it to the Grandmas Who Play Favorites account with a caption about small victories and reclaiming what was almost destroyed. Within an hour, the post had 2,000 likes and hundreds of comments celebrating Zoe’s hair coming back.

People wrote that they hoped Ruth saw the post and understood what she’d tried to take away. Someone commented that Zoe’s curls looked like they were growing back even more beautiful than before, like her hair was making a statement. Others shared their own photos of children’s hair growing back after similar incidents, creating this whole thread of recovery and resilience.

The support felt overwhelming in the best way. All these strangers genuinely caring about my daughter’s healing. Tom got a call from Camila 3 days later while we were eating dinner. He stepped into the other room to talk, but I could hear his surprised tone through the wall. When he came back, he sat down slowly and told me Ruth had apparently been doing her therapy homework consistently for weeks now.

Camila said Ruth’s therapist had her journaling about each granddaughter and identifying where her different feelings came from, and Ruth was starting to understand that her favoritism wasn’t just preference, but actual emotional abuse towards Zoe. Tom looked skeptical saying it, like he wanted to believe his mother could change, but didn’t trust it yet.

Camila had also mentioned that Ruth asked if she could write another letter, taking full responsibility this time, not just apologizing for the haircut, but acknowledging the entire pattern of favoritism. Tom and I looked at each other across the dinner table. Both of us weighing whether we were ready to read another letter after the previous ones had been so centered on Ruth’s feelings.

I finally said we’d read it, but weren’t making any promises about what would happen after. The letter arrived 4 days later in a plain envelope with Ruth’s handwriting that looked less steady than usual, like she’d been nervous writing it. I made Tom read it first while I finished putting Zoe to bed, needing him to tell me if it was worth my time or just more excuses.

He came into Zoe’s room 20 minutes later with the letter in his hand and said I should read it, that it was different from the others. I sat on the couch and opened the two pages of Ruth’s handwriting, immediately, noticing that she’d crossed out and rewritten several sentences like she’d struggled with getting the words right.

The letter started by naming what she’d done as wrong without any qualifications or excuses. Ruth wrote that she had treated Zoe as less important than her other granddaughters because of Zoe’s appearance and that this was racism and favoritism and emotional abuse. She didn’t say she hadn’t meant to hurt anyone or that her intentions were good.

She just said she was wrong and that she’d damaged her relationship with her granddaughter in ways that might never fully heal. The second page outlined specific changes Ruth said she was committed to making, like examining her reactions to the girls before speaking and catching herself when she started to compare them.

She wrote that she understood we had no reason to trust her and that she needed to earn back trust through consistent changed behavior over a long period of time. The letter ended without asking for forgiveness or requesting contact, just saying she understood she’d broken something that might not be fixable and that she accepted responsibility for that.

I read it twice looking for the usual self-centered language or victim mentality, but couldn’t find it. Tom sat next to me and asked what I thought, and I said it was better, but that words on paper didn’t mean Ruth had actually changed how she felt about Zoe. We decided to show the letter to Zoe’s therapist at our next appointment to get her professional opinion on whether it showed real progress or just better apologizing skills.

The therapist read Ruth’s letter carefully during our session while Zoe played with toys in the corner, then looked up and said it showed genuine progress in Ruth’s understanding of her behavior. She explained that most people who show this level of favoritism never reached the point of naming it as abuse or acknowledging harm without centering their own feelings.

The therapist said we could consider a very brief supervised visit in a neutral location if we felt ready, emphasizing the if and the supervised and the brief. Tom and I talked about it in the car on the way home. Both of us feeling torn between protecting Zoe and wondering if Ruth had actually done enough work to deserve a chance.

I said I wanted to wait another month to see if Ruth maintained this new awareness or if it was just temporary guilt. Tom agreed immediately, saying his mother had a pattern of seeming to understand something and then reverting to old behavior when the pressure was off. We told Camila our decision and she said she’d let Ruth know, adding that Ruth had expected us to need more time and hadn’t pushed for immediate contact.

6 months after Ruth cut Zoe’s hair, we finally agreed to a 30-inut supervised meeting at a public park with the understanding that we’d leave immediately if anything felt wrong. Tom called his sister and brother to arrange it, asking them to bring Olivia and Kloe so Ruth would have to demonstrate treating all three girls equally right from the start.

Camila said she’d been waiting for us to be ready for this and had already talked to Ruth about appropriate behavior. The morning of the meeting, I dressed Zoe in her favorite purple shirt and put a clip in her growing curls, wanting her to feel pretty and confident. Tom kept checking his watch during the drive to the park, clearly nervous about seeing his mother for the first time in half a year.

We arrived early and sat on a bench where we could see the parking lot, watching for Ruth’s car. She pulled in exactly on time with Camila’s van right behind her, and I felt my whole body tense watching Ruth get out and walk toward the playground. Ruth looked older than I remembered, her hair grayer, and her movements more careful.

She’d brought a small bag with her that turned out to hold three identical stuffed animals, cheap ones from the grocery store, but exactly the same. When the girls ran up, Ruth knelt down to their level instead of just bending over, and she spoke to all three of them before singling anyone out.

She told Zoe her curls looked beautiful and asked about her favorite color without mentioning Olivia or Khloe’s hair at all. Zoe hung back at first, standing half behind my leg while Ruth talked, clearly remembering that Grandma had hurt her, even if she couldn’t fully articulate how. Ruth didn’t push or try to force affection, just kept her voice gentle and asked Zoe about her toys at home.

When Zoe mentioned her stuffed elephant, Ruth asked what the elephant’s name was and actually listened to the answer instead of redirecting attention to the other girls. She gave each girl their identical stuffed animal at the same time, not making a big production out of any one gift. Olivia asked why hers wasn’t bigger since she was the oldest, and Ruth gently said all the cousins were equally special and deserved equal gifts.

The whole interaction felt stiff and awkward, like Ruth was consciously monitoring every word in action, but she was genuinely trying. After exactly 30 minutes, Tom stood up and said it was time for us to go. Ruth nodded and told Zoe she hoped to see her again soon, then stepped back without trying to hug her or push for more contact.

Zoe waved goodbye, but didn’t move toward her grandmother, and I took that as a healthy boundary my daughter was setting for herself. We scheduled visits every other week at first, keeping them to an hour at Ruth’s house with Tom and me present the whole time. Ruth would greet all three girls at the door with the same enthusiasm, bending down to their level and asking about their weeks without singling anyone out.

I watched her face during those early visits, seeing the way she had to pause before speaking, like she was running through a mental checklist of how to treat them equally. She’d catch herself reaching for Olivia’s hair and pull her hand back, then make a point of complimenting Zoe’s outfit or asking about her toys. The effort was visible in every interaction, this conscious work of fighting against instincts she’d spent years building.

Zoe stayed close to me during the first few visits, playing with her toys, but keeping one eye on her grandmother. She’d answer Ruth’s questions, but didn’t volunteer information or run to show her things like she used to when she was younger. The easy trust was gone, replaced by this careful distance that broke my heart, even though I knew it was healthy.

By the second month, Zoe would sit near Ruth during visits and accept the snack she offered. But she never climbed into her lap or asked for hugs. Ruth noticed this shift, and I could see the pain in her eyes when Zoe chose to sit between me and Tom instead of next to her grandmother. but she didn’t push or try to force affection.

Tom talked to his sister every few weeks, getting updates on how the new family dynamic was affecting everyone. Camila called one afternoon while I was making dinner and asked if she could stop by to talk. She arrived with coffee and sat at my kitchen table looking tired but lighter somehow, like she’d put down something heavy she’d been carrying.

She told me that Olivia had thrown a tantrum last month when Ruth gave her the same birthday present as Kloe, a regular art set instead of the elaborate craft station she’d gotten the year before. Camila had let her cry it out and then explained that grandma was learning to treat all her granddaughters the same and that Olivia wasn’t more special than her cousins just because she was older.

The conversation had been hard, but Olivia seemed to understand and over the past few weeks she’d started asking to play with Zoe and Kloe more instead of expecting them to watch her have special experiences. Camila said Olivia had even shared her favorite doll with Kloe last week without being asked, something she never would have done before when she saw herself as Ruth’s chosen one.

The shift was hard for Olivia in some ways, losing that special status she’d grown used to, but Camila could see her daughter developing real empathy instead of the entitled attitude that had been growing. She said all three girls seemed more relaxed at family gatherings now, playing together instead of Olivia performing for Ruth while the others watched.

8 months after Ruth cut Zoe’s hair, I sat in the therapist’s office for our regular check-in without Zoe present. The therapist pulled out her notes and told me that Zoe had made excellent progress in processing the rejection and rebuilding her self-image. She was confident, happy, and secure in our family’s love for her. But then the therapist’s expression shifted, and she said something that made my chest tight.

She explained that while Zoe was doing well now, she’d likely always carry some memory of this period, even if the details got fuzzy as she grew older. The experience of being treated as less valuable than her cousins during such important developmental years might surface again as she got older, affecting how she viewed family relationships and her place in them.

The therapist recommended continuing therapy periodically as Zoe developed, checking in at different stages to help her process the experience through new lenses as her understanding deepened. I posted an update on the Grandmas Who Play favorites account that evening, sharing resources about childhood favoritism and its long-term effects.

The account had become something bigger than just my story, a place where people dealing with similar situations could find support and validation. I kept it active with occasional posts about our ongoing journey. The small victories and continuing challenges of rebuilding family relationships after such deep damage.

Zoe’s curls had grown back full and thick, bouncing around her shoulders when she ran. And every time I saw them, I felt this fierce pride mixed with lingering anger at what Ruth had tried to take from her. Our family would never be the same as it was before. That easy trust and assumed love replaced by careful boundaries and supervised contact.

But my daughter knew without any doubt that her parents would always protect her, that she was valued.