On March 14th, 1853, in a parish courthouse somewhere along the Mississippi River corridor of Louisiana, a transaction occurred that would be deliberately emitted from official auction records for over a century. A pregnant woman was sold for 12, not $12, 12, the price of a loaf of bread. Court documents show the sale was legal, witnessed by seven men whose signatures still appear on the deed of sale.

Yet, the woman’s name was never recorded in any parish registry before or after that day. Local historians discovered the receipt in 1897, sealed inside a wall during courthouse renovations, and immediately rearied it. What they found written on the back of that receipt made them choose silence over truth.

Tonight, we reveal what was hidden and why the descendants of those seven witnesses spent generations trying to ensure this story died with them.

The transaction that occurred on that March morning was not an anomaly born of chaos or confusion. It was deliberate, calculated, and entirely legal under the laws that governed Louisiana in the years before the Civil War tore the nation apart.

St. Helena Parish in 1853 was a place where Spanish moss hung so thick from the live oaks that daylight struggled to reach the ground, where the air tasted of river silt and sugar cane smoke, and where the wealth of the land was measured not in acres but in human beings. The parish sat in the fertile crescent between Baton Rouge and the Mississippi border, close enough to the river to prosper, remote enough to keep its secrets.

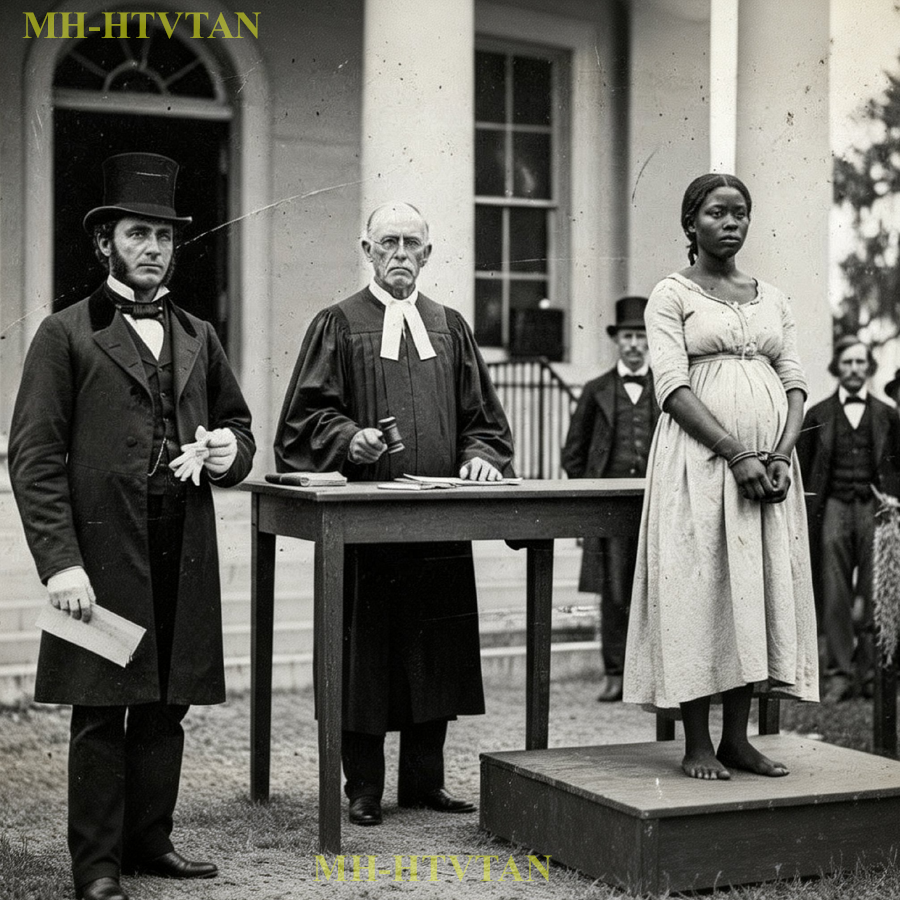

The town of Greensburg served as the parish seat, a collection of whitewashed buildings arranged around a courthouse square where business was conducted with the formality of church service. Every Saturday, the courthouse steps became an auction block. Furniture, livestock, land, and people changed hands with equal bureaucratic efficiency.

The auctioneers knew their business. The buyers knew their limits. And everyone understood that what happened on those steps was sanctioned by law, blessed by custom, and enforced by men who believed themselves to be the architects of civilization itself. In the spring of that year, three men held particular power in St. Helena Parish.

Judge Amos Krenshaw presided over the district court with the authority of scripture. At 62 years old, he had spent four decades interpreting laws written to protect property above all else. His decisions shaped the parish like a river shapes its banks slowly, inevitably, with a force that seemed like nature itself.

Below him, in influence, but equal in ambition, was Duncan Fairholm, a plantation owner whose family had controlled over 4,000 acres of prime cotton land since Louisiana became a state. Fairholm was 47, educated in Charleston, fluent in French, and ruthless in business. His plantation, Bellamont, employed an overseer named Silas Guthrie, a man whose reputation for cruelty kept the enslaved population compliant through fear alone.

The third man in this trinity of power was Nathaniel Puit, the parish tax assessor and recorder of deeds. Puit was younger, 39, hungry for status in a society where family name meant everything and his meant nothing. He had arrived in Louisiana from Virginia with forged letters of introduction and an understanding that in the chaos of westward expansion, a man could reinvent himself if he was willing to do what others would not.

These three men intersected on the morning of March 14th because of a woman whose existence had been carefully erased from every record they controlled. Her name was Claraara. She had been born on a tobacco plantation in Virginia approximately 23 years earlier. The word approximately matters here because enslaved people were often not afforded the dignity of recorded birth dates.

She had been sold south at age 15, separated from her mother and two younger siblings in a Richmond auction house on a Tuesday morning in late summer. The man who purchased her was Edmund Fairholm, Duncan’s father, who died of cholera in 1849, leaving his entire estate, including 47 human beings, to his son. Claraara worked in the main house at Bellamont.

She was clever with numbers, could read despite laws forbidding it, and possessed a quiet dignity that Duncan Fairholm first noticed, then resented, then sought to destroy. In October of 1852, Clara became pregnant. She never spoke the father’s name aloud. She did not need to. Everyone in the main house knew. The enslaved women who worked alongside her knew.

Duncan Fairhomem’s wife Margaret knew, and Duncan himself knew with a certainty that filled him with such rage that he could barely look at Claraara without his hands shaking. Because the father was not Duncan, it was his younger brother, William. William Fairholm was everything Duncan was not. Where Duncan was severe, William laughed easily.

Where Duncan saw human beings as agricultural investments, William saw the fundamental evil of the system he benefited from and lacked the courage to oppose it. He was 28 years old, unmarried, and living in the overseer’s cottage at the edge of Bellmont’s property, ostensibly managing the northern fields, but mostly drinking and reading abolitionist literature he smuggled from New Orleans.

His relationship with Claraara began as conversation. She brought meals to the cottage twice daily. He asked her questions about her life before Bellamont. She answered cautiously at first, then with increasing honesty, as she realized he listened differently than other white men. Over months, conversation became something else, something that crossed every boundary their world had constructed.

When Claraara’s pregnancy began to show in late December, William did something unprecedented. He went to his brother and offered to purchase Claraara’s freedom. The conversation occurred in Duncan’s study on a Saturday evening. No written record exists of what was said, but what happened next was documented with meticulous precision.

Duncan refused the offer, more than refused. He was insulted by it. In his view, William had violated the sanctity of property rights, had endangered the racial hierarchy upon which their entire society depended, and had embarrassed the fairome name in a way that could destroy their standing if it became public knowledge.

William argued that he loved Claraara, that the child was his, that they should be allowed to go north, to a free state, to build a life beyond the reach of Louisiana law. Duncan’s response was to immediately sell Clara, not to a slave trader who might take her far away where William could never find her.

That would be too simple, too merciful. Duncan wanted his brother to watch, to witness, to understand the consequences of what Duncan called his betrayal. He arranged for Clara to be included in a public auction scheduled for March 14th, a routine sale of property seized for unpaid debts. the courthouse steps, full public view, entirely legal.

But Duncan added a condition that revealed the depth of his cruelty. He set Clara’s minimum bid at 12 cents. The amount was deliberate. In 1853, the average price for an enslaved woman of childbearing age in Louisiana was between $800 and $1,200. By setting the price at 12, Duncan achieved several objectives simultaneously.

He demonstrated that Claraara had no value to him. He humiliated William by showing that the woman he claimed to love was worth less than a newspaper. And most cunningly, he ensured that no legitimate buyer would bid. Because in the economy of slavery, price signaled quality. A woman offered for 12 cents must be damaged, diseased, unsuitable for work.

No plantation owner would risk even minimal investment on such obvious refues. Duncan knew exactly one person would bid. His plan was not to sell Clara to a stranger. It was to sell her to someone who would ensure her suffering continued under circumstances William could not prevent. He was selling her to Silas Guthrie, his overseer.

The night before the auction, William Fairholm disappeared. He left no note, took no horse, simply walked away from Bellammont sometime after midnight, and was never seen in St. Helena Parish again. Some said he went north to join abolition movements in Boston. Others claimed he drowned himself in the Mississippi, unable to live with his powerlessness.

A few whispered that Duncan had him killed and buried in the cane fields where dozens of enslaved people were already interred in unmarked graves. The truth was simultaneously simpler and more disturbing. William had gone to Judge Krenshaw’s home in the hours before dawn and offered him everything he owned, approximately $3,000 in inheritance and land rights, for a single favor.

He wanted the judge to invalidate the sale, to declare it unlawful on some technicality, to give William time to find another solution. Judge Krenshaw listened to Williams plea with the expression of a man watching a child explain why the sky should be green instead of blue. When William finished, the judge asked a single question.

Did your brother sign the proper deed of sale? William admitted he had. Then the transaction is legal. Crenaw said, “Your grief does not supersede property law. Good evening, Mr. Fairome. William left that house understanding that every institution, every law, every powerful man in the parish would side with Duncan. Not because they were cruel, though many were, but because allowing William’s sentiment to override Duncan’s property rights would threaten the entire foundation of their economy.

If love could supersede ownership, the system would collapse. Clara spent her last night at Bellamont in the quarters, surrounded by women who braided her hair and sang songs that were older than Louisiana, older than America. songs carried from Africa in the bellies of ships. They knew they would likely never see her again.

They knew what men like Silus Guthrie did to women they owned. One of the women, an elderly cook named Bethy, who had survived 50 years of bondage, pressed a small cloth bundle into Claraara’s hands. Inside was a knife barely longer than Claraara’s palm wrapped in oil cloth. “You hide this,” Bethy whispered. “You hide it good.

” And when the time comes, you do what needs doing. Claraara nodded. She understood. The knife was not for self-defense. It was for mercy. For her child, if things became unbearable, for herself, if there was no other escape, she sewed it into the hem of her dress that night, her fingers steady despite the fear that tasted like copper in her mouth.

The auction began at 10:00 in the morning under skies so gray they seemed to mirror the moral character of everything occurring beneath them. Approximately 40 people gathered in the courthouse square. Most were there for livestock and furniture. A few came specifically for the human merchandise. Nathaniel Puit stood on the courthouse steps with the deed of sale in his hands, reading from it in a voice designed to carry across the square.

He described Claraara with the same inflection he used for describing a lame horse. Female, age approximately 23 years. Housetrained, literate, though such skill is of questionable value. Currently with child, minimum bid 12 cents. A murmur rippled through the crowd. 12 cents. Something was wrong with this one.

Several men who had been prepared to bid immediately lost interest. Why risk investment on obviously defective property? Silus Guthrie stood near the front, his hat pulled low, his expression unreadable. He was waiting for the crowd to disperse, waiting for the moment when no one else would bid, when he could purchase Claraara for the pittance Duncan had arranged, when she would become his property to do with as he pleased.

But something unexpected happened. A man near the back of the crowd raised his hand. 12 cents, he called out, every head turned. The man was a stranger, tall, thin, wearing a traveler’s coat dusty from the road. His face was weathered in the way that suggested years of outdoor labor, but his bearing was wrong for a field hand. He stood too straight, looked people in the eye too directly.

Nathaniel Puit hesitated. You are bidding 12 cents for this property. I am Your name, sir? Isaiah Mercer. Puit glanced toward Silus Guthrie, who was staring at the stranger with an expression of genuine confusion. This was not part of the plan. Duncan had arranged for Guthrie to be the only bidder.

Who was this man? Do you have 12 cents, Mr. Mercer? Isaiah Mercer approached the steps, reached into his pocket, and placed 12 copper pennies on the podium where Puit stood. I do. from his position near the courthouse door. Judge Krenshaw watched this exchange with increasing interest. He had been present at the auction specifically to ensure Duncan’s plan proceeded smoothly.

But now an unknown variable had entered the equation. Puit looked desperately towards Silas Guthrie. The overseer’s face had gone red. He understood what was happening. If he bid 13 cents, he would reveal his interest. He would make public what was supposed to be a quiet transaction.

Duncan had specifically instructed him to wait until no one else bid to make it seem like he was doing Bellamont a favor by taking worthless property off their hands. But if he did not bid, Clara would go to this stranger. The seconds stretched. The crowd waited. Finally, Silas Guthrie spoke. 13 cents. Isaiah Mercer did not hesitate. 25 cents.

50 cents. Guthrie snapped. $1. The crowd was riveted. Now, this was not how these auctions typically proceeded. Something peculiar was happening. Two men bidding against each other for a woman being sold at refuge prices. What did they know that everyone else did not? Silas Guthrie bid $2. Isaiah Mercer bid five.

At $10, Guthrie stopped. Not because he lacked funds, but because Duncan had given him specific instructions. Do not overpay. Do not draw attention. The whole point was to acquire Claraara quietly to make it seem insignificant. But it was no longer insignificant. $10 once, Nathaniel Puit called out, his voice uncertain. $10 twice.

He waited, looking toward Judge Krenshaw for guidance. The judge gave a small nod. Sold to Mr. Isaiah Mercer for $10. Claraara, who had been standing to the side of the courthouse steps throughout this entire exchange, her hands bound in front of her, her pregnancy visible beneath the thin dress she wore, looked at the man who had just purchased her.

Isaiah Mercer met her gaze. And though his expression did not change, Claraara saw something in his eyes that made her breath catch. Recognition. The deed of sale was signed within minutes. Isaiah Mercer paid the $10 in coins that he counted out carefully onto Puit’s desk. Judge Krenshaw witnessed the transaction with his signature.

By law, Claraara was now the legal property of a man she had never met until that morning. But the irregularity of the sale had attracted attention. As Mercer led Claraara away from the courthouse, moving quickly toward a wagon waiting at the edge of the square, Duncan Fairholm emerged from inside the courthouse where he had been watching through a window.

Mr. Mercer, Duncan called out. His voice was sharp, accustomed to obedience. A moment of your time. Isaiah Mercer stopped. He did not release Claraara’s arm. When he turned to face Duncan, his expression was carefully neutral. Mr. Fair home. You are not from this parish. I am not. What brings you to St.

Helena? Business. Duncan took a step closer. He was trying to place this man trying to understand what had just happened. The auction was supposed to be controlled, predictable. This outcome was neither. What sort of business? My own sort, Mercer replied. His voice was quiet but firm. The transaction was legal.

The judge witnessed it. unless you have some objection to the sale. It was a challenge phrased as a question. Duncan recognized it immediately. If he objected, he would need to provide grounds. And what grounds could he offer? That he had deliberately undervalued Claraara to humiliate his brother.

That he had arranged for his overseer to purchase her for purposes Duncan preferred not to state publicly. “No objection,” Duncan said slowly. “Though I am curious. What do you intend to do with property you purchased for such a price? That is my business, Mr. Fair Holm. Good day. Isaiah Mercer turned and continued toward the wagon. Clara walked beside him, her mind racing. Nothing about this made sense.

This man had bid against Silus Guthrie, had paid $10, a significant sum, for a woman being sold as refu. And when she had looked into his eyes, she had seen something that terrified her more than anything that had happened in the past 4 months. He knew who she was. Not just her name, not just her situation.

He knew her. They reached the wagon, a simple farm cart with a canvas cover. Mercer helped her climb into the back, his touch impersonal, but not rough. Then he climbed onto the driver’s bench, took up the reinss, and urged the horse forward. They rode in silence through Greensburg, past the storefronts and houses, past the church with its white steeple, past the boundary where cultivated land gave way to pine forest.

Only when they were well beyond sight of the town did Isaiah Mercer speak. You do not remember me. Claraara’s voice was cautious. Should I? Richmond, August 1845. You were 15 years old. I was there the day you were sold. Clara’s blood went cold. You were at the auction. I was. Mercer kept his eyes on the road.

I was working for a man named Ephraim Dalton, a slave trader. I drove his wagons, managed his property. I watched you and your family stand on that block. I watched your mother scream when they separated you. I watched Edmund Fairhomem pay $700 and lead you away. Then you are no different than the rest of them,” Claraara said, her voice hard.

“I was no different,” Mercer corrected. “I am no longer that man.” He reached into his coat and withdrew a folded piece of paper. Without taking his eyes from the road, he handed it back to Claraara. “Read it.” Claraara unfolded the paper with shaking hands. It was a deed of manumission, a document that when properly executed and filed would grant freedom to an enslaved person.

The name on the document was hers. Claraara, no last name because she had never been granted one, but her description matched her age, the scar on her left forearm from a childhood burn. At the bottom of the document, unsigned, was a space for the owner’s signature. Isaiah Mercer’s signature.

I do not understand, Clara whispered. 8 years ago, I watched your family destroyed on an auction block, Mercer said. His voice was steady. But there was something beneath it, something that might have been shame or grief or both. I told myself I was just doing a job, that I was not responsible for the system, that I was just a small part of a large machine.

Then one night in New Orleans, I watched Ephraim Dalton beat a man to death over $5. I watched him do it slowly. And I realized that every person who participates, no matter how small their role, makes the machine function. So I left. I went north. I worked with people who were trying to dismantle what I had helped build.

He paused, navigating the wagon around a fallen branch. 3 months ago, a man came to a meeting in Cincinnati. His name was William Fairholm. He told us about a woman in Louisiana who was carrying his child. He told us his brother was going to sell her to an overseer known for brutality. He gave us the date and location of the auction.

He asked if anyone could help. Claraara’s hand moved instinctively to her stomach. William sent you. He paid me, Mercer said, “Not to purchase you. He paid me to bring you north to a safe house in Illinois. To a place where you and your child can be free.” Claraara stared at the deed in her hands. Freedom.

The word felt foreign. Impossible. A promise that had been weaponized against enslaved people for so long that she no longer trusted it. Where is William now? She asked. Mercer’s silence answered before his words did. He died two weeks ago. Fever, they said. He was in Kentucky trying to arrange passage for others.

The people I work with, they think it might not have been fever. They think someone from Louisiana tracked him down. Claraara closed her eyes. William, reckless, idealistic William, who had read her poetry and promised her things that could never be. William, who had at least tried, which was more than most men in his position would ever do.

Duncan had him killed, she said. It was not a question. We cannot prove it, but yes, I believe that. Just when we thought the worst of this story was behind us, when it seemed Claraara might finally find freedom, the true horror of what happened in St. Helena Parish is about to reveal itself.

If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries. Hit that like button to support our content, and do not forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this. Let us discover together what happens next. The wagon continued north through the afternoon, following roads that grew increasingly rough and remote.

Mercer explained the route they would take. They would avoid main roads, travel mostly at night, rely on a network of safe houses operated by free black families and sympathetic whites. It would take weeks to reach Illinois, months before Clara would be truly safe. But something was wrong. Clara could not articulate it precisely, but years of survival had taught her to trust her instincts.

And her instincts told her that Isaiah Mercer was lying, not about everything. His story about Richmond might be true. His shame might be genuine. But something about this rescue felt staged, performed as though he was following a script written by someone else. She thought about the auction, about how perfectly timed Mercer’s arrival had been, about how he had known exactly when and where to bid, about how easily he had outmaneuvered Silus Guthrie. Too easy.

Duncan Fairholm did not make mistakes. He planned everything with the precision of a general deploying troops. If he had wanted Claraara to go to Guthrie, she would have gone to Guthrie. Unless, unless Duncan had wanted something else to happen. The realization settled over Claraara like ice water. This was not a rescue. This was a hunt.

The wagon continued north through the afternoon, following roads that grew increasingly rough and remote. Mercer explained the route they would take. They would avoid main roads, travel mostly at night, rely on a network of safe houses operated by free black families and sympathetic whites.

It would take weeks to reach Illinois, months before Clara would be truly safe. But something was wrong. Clara could not articulate it precisely, but years of survival had taught her to trust her instincts. And her instincts told her that Isaiah Mercer was lying. Not about everything. His story about Richmond might be true.

His shame might be genuine. But something about this rescue felt staged, performed, as though he was following a script written by someone else. She thought about the auction, about how perfectly timed Mercer’s arrival had been, about how he had known exactly when and where to bid, about how easily he had outmaneuvered Silus Guthrie. Too easy.

Duncan Fairhomem did not make mistakes. He planned everything with the precision of a general deploying troops. If he had wanted Claraara to go to Guthrie, she would have gone to Guthrie, unless Duncan had wanted something else to happen. The realization settled over Claraara like ice water. This was not a rescue. This was a hunt.

They camped that night in a clearing several miles from the nearest settlement, deep enough in the forest that fire light would not be visible from the road. Mercer built a small fire and offered Claraara dried meat and cornbread. She ate mechanically her mind working through possibilities. If Duncan wanted her dead, he could have had her killed at Bellamont.

Simple, quiet. Enslaved women disappeared regularly. No one questioned it. But Duncan did not want her dead. He wanted William destroyed completely. And William was already gone, already beyond Duncan’s reach. So Duncan needed something else. He needed proof that William’s betrayal had consequences. He needed the child Claraara carried to suffer.

And more than that, he needed it to be William’s fault. The escape was designed to fail. Mercer was not rescuing Claraara. He was delivering her to something worse than Silus Guthrie. Somewhere along this route, they would be intercepted. Slave catchers. probably men who would claim Claraara was a runaway. The deed of sale would be declared fraudulent.

Claraara would be returned to Duncan under circumstances that would make her fate seemed like justice rather than cruelty. And because William had arranged this escape because he had paid for it because he had involved abolitionists in a conspiracy to steal property, Duncan would be able to say that his brother had brought about Claraara’s suffering.

That Williams sentiment had made things worse, not better. It was perfect revenge. The only question was when the trap would spring. Claraara waited until Mercer had settled on the opposite side of the fire, his back against a tree, his hat pulled low. She waited until his breathing deepened. Then she carefully reached into the hem of her dress and retrieved the knife Bethy had given her.

The blade was small but sharp. She tested the edge against her thumb, felt it bite. She could kill him right now while he slept. It would be easy. But then what? She was pregnant, alone, somewhere in Louisiana forest with no money, no map, no allies. Even if she made it to a road, she would be captured within days.

A pregnant black woman traveling alone would be stopped, questioned, returned to whoever claimed ownership. The knife was not the answer, but maybe honesty was. I know this is not real, Clara said quietly. Mercer did not move. For several seconds, she thought he might actually be asleep. Then he pushed his hat back and looked at her across the fire. Explain.

Duncan planned this. He wanted me to try to escape. He wanted it to fail. You are part of that plan. Mercer’s expression did not change. Why would I agree to such a plan? Money or safety? Maybe Duncan threatened to expose you for helping runaways. Maybe he offered to pay you more than William did. I do not know why, but I know this is not what you told me it was.

The fire crackled between them. Somewhere in the darkness, an owl called. Finally, Isaiah Mercer spoke. “You are smarter than William gave you credit for.” Claraara’s grip tightened on the knife. “So I am right.” Partially. Mercer sat forward, his elbows on his knees. Yes, Duncan knows about this escape. Yes, he planned for it to fail.

But you are wrong about why I am helping him. Then why? Because if I did not, someone else would. And that someone else would deliver you directly to slave catchers who would hurt you in ways I will not describe. Duncan gave me a choice. lead you north and let his men intercept us in a way that leaves you physically unharmed or refuse and watch him give the job to men who would make you wish you had never been born.

Claraara laughed bitterly. So you chose the merciful betrayal. I chose to give you a chance. What chance? You just said we will be intercepted. We will be. Tomorrow afternoon approximately 20 mi north of here. Four men will be waiting on the road. They will have papers declaring you a fugitive.

They will have authorization from Judge Krenshaw to return you to Belmont. And legally, they will be completely within their rights. Then I have no chance. You have exactly one chance, Mercer said. He reached into his saddle bag and withdrew a leather pouch. He tossed it across the fire to Clara. There is $150 in that pouch.

There is also a letter of introduction to a family in Nachez. free people of color who can help you disappear. Not north. North is where Duncan expects you to run, but south to New Orleans, then by ship to Mexico. It is a longer route, more dangerous, but it is possible. Claraara opened the pouch.

The money was real. The letter was real. Why would you do this? Because I meant what I said earlier. I’m not the man I was in Richmond. And because William Fairhomem, whatever his faults, tried to do something decent, I will not let Duncan Fairhomem turn that decency into a weapon. But you are still going to betray me.

You are still going to let Duncan’s men intercept us. They are going to intercept someone, Mercer corrected. It does not have to be you. He stood and walked to the back of the wagon. When he returned, he was carrying a bundle of clothing, women’s clothing, a dress similar to Claraara’s, but larger. A shawl, a bonnet.

There is a settlement 8 mi south of here. Small place, mostly free black families and poor whites. There is a woman there named Ruth Chambers. She is approximately your height, your complexion, and she is dying. Consumption. She has perhaps weeks left. I spoke with her yesterday. I paid her family $50 to help us. Claraara stared at him.

I do not understand. Tomorrow morning, you take this money and these clothes. You walk south to the settlement. You tell the Chambers family that Isaiah sent you. They will hide you until the men looking for you have passed through the area. Then they will help you get to Natchez. From there, you follow the letters instructions.

And you, Ruth Chambers, will take your place in this wagon. She is too ill to walk more than a few steps, but she can sit upright in a bonnet and shawl. From a distance, she will look enough like you. When Duncan’s men intercept us tomorrow, they will take her. By the time they realize their mistake, you will be gone.

Clara’s mind reeled. Ruth will die. Ruth is already dying, and her family needs money to bury her properly to care for her children. This way, her death serves a purpose. This is insane. This is your only chance, Mercer said flatly. Duncan has men watching every route north. He has money and power and the law on his side.

You cannot fight him directly. You can only disappear so completely that he cannot find you. Claraara looked down at the knife in her hand. Then at the money, then at Isaiah Mercer, whose face was half shadowed by firelight. If I do this, if I run, Duncan will know you helped me. He will come after you. He will try,” Mercer agreed.

“But I am harder to catch than you are, and I have friends who can make me disappear, too.” “Why?” Clara asked. The word came out broken. “Why would you risk this for me?” Mercer was quiet for a long moment. When he spoke, his voice was softer than it had been all day. In Richmond, when they separated you from your mother, you did not scream. You did not fight.

You stood on that block and you looked at the men bidding on you with an expression that said you knew exactly who they were and what they were capable of. You were 15 years old and you had more dignity than any of them would ever possess. I have seen that expression in my dreams for 8 years. It is time I did something to earn the right to forget it.

Claraara felt tears burn behind her eyes, but refused to let them fall. Crying was a luxury enslaved women could not afford. Tears were interpreted as weakness, as submission, as evidence that they had accepted their condition. She had learned early to keep her grief internal, to let it calcify into something harder. “There is something else you should know,” Mercer continued.

His voice had dropped lower, as though the forest itself might be listening. About Duncan Fairholm. What about him? William told us things before he died. Things about his brother, about Bellamont. Mercer paused, choosing his words carefully. You were not the first. Claraara’s blood went cold. The first what? The first woman Duncan sold to Silus Guthrie. There were three others.

Over the past 5 years, all of them house servants. All of them young. Duncan would arrange some minor infraction, some excuse to remove them from the main house. Then he would sell them to Guthrie at auction. Always for suspiciously low prices. Always legally documented. Always witnessed by Judge Krenshaw.

What happened to them? Two died within a year. One from injuries Guthrie claimed were accidental. The other from what was called fever, though the enslaved people at Bellamont said she had been beaten so badly she never recovered. The third woman, her name was Sarah. She disappeared entirely. Guthrie claimed she ran away. No one ever saw her again.

Claraara thought of Bethy, the elderly cook who had given her the knife. Bethy would have known these women, would have watched them disappear one by one, would have understood exactly what fate awaited Claraara if she ended up in Guthri’s possession. Why would Duncan do this? Claraara asked, though she suspected she already knew the answer.

Because he could, Mercer said simply, sir. Because the law gave him absolute power over the people he owned. And absolute power reveals what men truly are. Duncan Fairholm is a man who enjoys the suffering of others, particularly women, particularly women who show intelligence or dignity or any quality that threatens his sense of superiority.

And Judge Krenshaw allowed this. Judge Krenshaw facilitated it. Every sale was legal. Every transfer of property properly documented. The judge never asked why these women were being sold so cheaply. Never questioned the pattern. He simply signed the papers and collected his fees. Claraara looked down at the knife in her hand.

Three women before her. All of them destroyed by the same mechanism. All of them erased from history as thoroughly as if they had never existed. William knew about this. He discovered it about a year ago. Found records in Duncan’s study. That was when he started reading abolitionist literature.

When he started believing the system itself was the problem, not just individual cruelty within it. He tried to convince Duncan to free the enslaved people at Bellamont. Offered to forfeit his own inheritance if Duncan would release them. Duncan laughed at him. Mercer fed another branch to the fire.

When you became pregnant, William saw it as his chance to do something right, to save at least one person from the machine. He contacted abolitionists in Cincinnati, paid them everything he had, made arrangements for your escape. But Duncan found out how. We think someone in Cincinnati betrayed us. Someone who sold information to slave catchers who then sold it to Duncan.

By the time William realized the escape plan was compromised, it was too late. Duncan had already restructured the whole auction to ensure you would end up exactly where he wanted you. Then why did William go to Kentucky? If he knew the plan had failed. Mercer’s jaw tightened. Because he was trying to find another way.

He thought if he could reach the Underground Railroad network, if he could get messages to conductors who operated in Louisiana, he could arrange a secondary rescue, something Duncan would not anticipate. But Duncan found him first. Duncan’s reach is longer than any of us understood. He has connections to slave catchers across five states, men who make their living hunting human beings.

When William started asking questions in Kentucky, someone reported it. 3 days later, William was dead. Claraara absorbed this information slowly. William, foolish and idealistic. William had tried, had actually tried. More than that, he had kept trying even after his first plan failed.

That had to count for something, even if it ultimately accomplished nothing. The fever, they said, killed him,” Claraara asked. “What really happened? We will never know for certain.” His body was found in a boarding house in Louisville. The proprietor said William had been sick for 2 days, complained of stomach pain, vomiting, died in his sleep.

But one of the abolitionists who saw the body afterward said William’s fingernails were blue. His lips were discolored. Those are signs of poisoning, not fever. Duncan poisoned his own brother or paid someone to do it. Either way, William became a problem Duncan needed to eliminate. And Duncan is very good at eliminating problems while keeping his own hands clean.

Claraara thought about this, about a man so consumed by the need for control that he would murder his own blood relative, about a system that gave such men power and called it civilization. If Duncan could kill William and make it look natural, Claraara said slowly, then he could kill you, too. You understand that? Yes. this plan you have sending me south while Ruth takes my place.

It will only work if Duncan believes you were genuinely trying to help me escape. If he suspects you deliberately failed him, you are a dead man. I know. Then why risk it? Mercer looked at her directly. Because I am tired of being the person who looks away. I am tired of telling myself that I’m just following orders, just doing a job, just trying to survive in a system I did not create.

Every person who makes that excuse, who chooses their own safety over someone else’s suffering, makes the system stronger. I cannot dismantle slavery by myself. But I can save one person. I can do one thing that matters. It was, Clara realized, the same logic that had motivated William. The same futile, beautiful logic that got idealistic people killed.

But it was also the only logic that ever changed anything. Clara made her decision. I will go south, she said. But I need to know something first. The Chambers family. How did you find them? How did you arrange this? I have been traveling through Louisiana for 3 months preparing for your escape. I made contacts in several communities.

Offered money to families who might be willing to help. The Chambers family was one of three who agreed. Three families? You planned multiple escape routes? I planned for contingencies. Duncan is not the only one who can think several moves ahead. Claraara felt something shift inside her. This man, this stranger who had participated in her family’s destruction 8 years ago, had spent 3 months preparing to save her, had risked his life to create options, had thought through scenarios and backup plans with the same meticulous care Duncan applied

to his cruelties. Perhaps redemption was not a single dramatic gesture. Perhaps it was the slow, methodical work of becoming someone different than you had been. What about Ruth? Clara asked. When Duncan’s men realize they have the wrong woman, what will they do to her? Nothing, Mercer said.

She will already be dying. By the time they discover the switch, Ruth will likely be unconscious or delirious from fever. They cannot torture someone who is that far gone. and they cannot prove she willingly participated in a deception. For all anyone knows, I made an honest mistake. I believed Ruth was you.

Duncan will not accept that explanation. Duncan does not have to accept it. He just has to acknowledge that he cannot prove otherwise. And without proof, even Duncan Fairholm has limits to what he can do publicly. Clara was not entirely convinced, but she had no better alternative. She thought about Ruth Chambers, a woman she had never met, who was sacrificing her final days to give Clara a chance at freedom.

It was a debt that could never be repaid. “I want to meet her,” Clara said before I leave. I want to thank her. “That is not wise. The less you know about each other, the safer you both are.” “I do not care about safe,” Clara said, her voice harder than she intended. “A woman is dying for me. The least I can do is look her in the eye and tell her I will not waste what she is giving me.

Mercer studied her for a long moment. Then he nodded. We will stop at the settlement in the morning. You will have 15 minutes. No more. They reached the chamber settlement just after dawn. It was less a town than a collection of cabins arranged around a common well home to perhaps 30 people. free black families mostly along with a few white families too poor to care about racial hierarchies.

The kind of place that appeared on no official maps that existed in the gaps between parishes that survived by being invisible to those who might want to destroy it. Ruth Chambers lived in the smallest cabin at the edge of the settlement. Her husband had died 2 years earlier in a logging accident. Her children, three of them ranging from age 4 to 12, were being cared for by neighbors, while their mother spent her final days in relative peace.

Relative, because consumption did not allow for peaceful deaths. It hollowed you out slowly, turned your lungs into useless meat, made every breath a battle you knew you would eventually lose. Clara entered the cabin with Mercer behind her. The interior was dim, lit only by a single window covered with oiled paper. The air smelled of sickness and sage.

The latter burned in a futile attempt to mask the former. Ruth lay on a narrow bed against the far wall. She was thin enough that her body barely raised the blanket covering her. Her skin had the grayish cast of someone whose organs were failing, but her eyes, when she looked at Claraara, were clear. You are the one, Ruth said.

Her voice was barely a whisper. I am Claraara. They told me you were worth saving. I wanted to see if that was true. Claraara moved closer to the bed. I do not know if I am worth what you are giving. Nobody is worth a life, Ruth said. But that is not why I agreed to help you. I agreed because my children need what Mr.

Mercer paid. Because I am dying anyway and because if I have to die, I would rather die doing something that means something. Your children, Claraara said, what will happen to them? My sister will take them. The money Mr. Mercer gave us will be enough to feed them through the winter.

Maybe enough to buy a small plot of land where they can grow their own food. It is more than I could have given them otherwise. Claraara felt tears burning again. She knelt beside the bed, took Ruth’s hand. The bones felt like bird bones, light and fragile. I will remember you, Claraara said. I will tell my child about you, about what you did.

Your name will not be forgotten. Ruth smiled weakly. Names do not matter much where I am going. But if it comforts you to remember, then remember, just make sure you live. Make sure that baby lives. Do not let me trade my death for nothing. I will live. Clara promised. Whatever it takes. Good. Ruth’s eyes fluttered closed. Now go. Mr.

Mercer will tell you what to do next. And do not look back. Looking back only makes the leaving harder. Claraara squeezed Ruth’s hand once more, then stood. As she turned toward the door, Ruth spoke again. One more thing. When they take me tomorrow, when Duncan Fairholm’s men realize I am not you, they will be angry. They might say cruel things.

They might threaten me, but they will not hurt me. I will make sure of that. How? Ruth opened her eyes again. There was something in them now, something fierce, despite the weakness of her body. Because I will already be dead. Claraara froze. What do you mean? Mercer stepped forward. Ruth and I discussed this.

The timing needs to be precise. If she dies during the interception before Duncan’s men can question her, they have no leverage. They cannot prove deception. They cannot punish anyone. All they can do is admit they failed. “You are planning to die at exactly the right moment?” Claraara asked incredulous. “I am planning to die on my own terms,” Ruth corrected.

consumption will kill me within weeks anyway. This way I choose when and how. This way my death serves a purpose instead of just being another tragedy. Claraara understood. Then Ruth had medicine, something the settlement doctor had given her, probably lord or morphine intended to ease her pain in the final days. and she was planning to take too much of it deliberately to time her death so that it occurred during the interception making Duncan’s entire plan collapse.

It was brilliant and horrible in equal measure. You have thought of everything, Claraara whispered. No, Ruth said. Mr. Mercer thought of everything. I am just agreeing to it. Now go before I start coughing again and ruin this dramatic moment. Claraara wanted to say more. Wanted to explain that she understood the magnitude of what Ruth was doing.

That she would carry this debt for the rest of her life. That she would make sure Ruth’s children knew their mother died a hero. But Ruth’s eyes had closed again, her breathing shallow and labored. And Mercer was already at the door, gesturing for Claraara to follow. So she left. She walked out of that dim cabin knowing she would never see Ruth Chambers again.

Knowing that within 2 days the woman lying on that bed would be dead, would have died specifically to give Claraara a chance at life. Outside the morning sun was already heating the air. Mercer handed Claraara the leather pouch with money and the letter of introduction. There is a path behind this cabin that leads south through the forest, he said.

Follow it for approximately 3 mi. It will bring you to a road. Take the road west until you reach a tavern called the Black Swan. The owner’s name is Marcus. Tell him Isaiah sent you. He will know what to do next. And then and then you follow the instructions in the letter. Trust no one who does not use the passwords written there. Move only at night.

Avoid main roads. Get to Nachez. Get on a ship. Get to Mexico. disappear so completely that Duncan Fairholm spends the rest of his life wondering what happened to you. Clara nodded. She adjusted the bundle of clothes under her arm, felt the weight of the money pouch. What about you? She asked. I will continue north with Ruth.

I will deliver her to Duncan’s men, and then I will disappear too. He will hunt you. Let him try. Mercer smiled grimly. I have been running from things my whole life. I am very good at it. Claraara wanted to thank him. Wanted to say something profound about redemption and second chances and the possibility of change. But words felt inadequate.

So instead she did something unexpected. She embraced him. Mercer stiffened clearly not expecting physical contact. Then slowly carefully he returned the embrace. Thank you. Claraara whispered. Survive. Mercer replied. That is all the thanks I need. They separated. Claraara turned toward the path Ruth had indicated.

She did not look back. Looking back only made the leaving harder. Behind her, Isaiah Mercer watched until she disappeared into the trees. Then he returned to the cabin where Ruth Chambers laid dying, where a plan had been set in motion that would either save Clara’s life or destroy everyone involved. The next 24 hours would determine which.

Claraara left before dawn, carrying the leather pouch and wearing the bundle of clothes over her arm. Mercer watched her go, a silhouette against the gray pre-dawn light, then turned to hitch the wagon. By the time the sun rose, Ruth Chambers was sitting in the back of the wagon, wrapped in Claraara’s shawl, her face hidden by the bonnet.

She was so thin that the pregnancy pillow Mercer had fashioned from rags and secured around her waist looked almost believable. They traveled north through the morning. Ruth did not speak. The consumption had taken most of her voice weeks ago. She simply sat swaying with the motion of the wagon. Her breathing labored. At approximately 2:00 in the afternoon, four men on horseback appeared on the road ahead.

They matched Mercer’s description exactly. Hard men armed with rifles and the confidence of people who knew the law would never question their actions. The leader, a man named Porter, approached the wagon with papers in his hand. Isaiah Mercer. Yes, we have a warrant for the return of fugitive property.

A negro woman named Claraara absconded from Bellamont Plantation. We have reason to believe she is in your possession. I purchased that woman legally. Mercer said, “I have the deed of sale.” The deed was obtained under false pretenses. Judge Krenshaw has voided the transaction. The woman is to be returned to her rightful owner. Porter moved to the back of the wagon.

He pulled aside the canvas covering. Ruth Chambers looked up at him with eyes that were fever bright and already halfway to another world. “This her?” Porter asked. One of his companions rode closer, studying Ruth’s face. hard to tell with the bonnet. “Make her stand up.” “She is ill,” Mercer said. “I did not ask. Make her stand.

” Mercer climbed into the back of the wagon. Gently, he helped Ruth to her feet. She swayed. Nearly fell. The pregnancy pillow shifted slightly beneath the shawl. Porter’s eyes narrowed. “She looks wrong.” “Consumption,” Mercer said. She caught it on the journey. I was bringing her back south because she is too ill to travel north.

convenient. Porter grabbed Ruth’s arm, pulled her toward him. The bonnet fell back. Ruth’s face was gaunt, her skin grayish. She bore perhaps a passing resemblance to Clara if you squinted and did not look too closely. But up close, the differences were obvious. This is not her, Porter said slowly.

I assure you, this is the woman I purchased from the auction in Greensburg. You are lying. Porter released Ruth so roughly that she collapsed back onto the wagon bed. He turned to his men, “Search everything. She is here somewhere.” They tore apart the wagon, ripped through supplies, checked beneath the driver’s bench, examined every inch of canvas.

They found nothing because there was nothing to find. Porter stood in the road, the papers in his hand now meaningless. He had been paid to intercept a specific woman. He had been promised it would be simple, and now he was returning to Duncan Fairholm empty-handed. “Where is she?” he demanded.

“I do not know what you are talking about,” Mercer said calmly. “This is the woman I purchased. If she is not the woman you are looking for, that is not my concern.” Porter took a step forward. Duncan Fairholm will hear about this. I hope he does. Perhaps he will explain why he is harassing law-abiding citizens over property disputes. It was a stalemate.

Porter knew he had been outsmarted but could not prove it. If he killed Mercer, he would have to explain to Judge Krenshaw why he had murdered a man who appeared to be innocent. If he took Ruth, he would have to explain why he had seized a dying woman who clearly was not the fugitive they sought. One of Porter’s men, a former slave catcher named James Ridley, had been studying Ruth carefully.

He had participated in dozens of captures over his 15-year career. He knew how to assess human property, and everything about this situation felt wrong. “We need to question her,” Ridley said, gesturing to Ruth. Porter crouched beside Ruth, who was still lying in the wagon bed where she had fallen. Her eyes were open but unfocused.

Her breathing had become shallow and irregular. “Where is Clara?” Porter demanded. “What did you do with her?” Ruth’s eyes focused on Porter with visible effort. And then, impossibly, she smiled. “Gone,” she whispered. “By your reach. Beyond Duncan Fairholm’s reach, she is free.” “Where? I will never tell you.

” Ruth’s smile widened, blood now visible on her teeth. You can beat me. You can torture me, but I will be dead long before you get any answers. I made sure of that. Porter understood. Then this woman had poisoned herself. Had deliberately taken something that would kill her during this exact confrontation.

Had turned her own death into a weapon against Duncan’s plan. “You stupid woman,” Porter said, though his voice had lost its certainty. You think this helps anyone? Duncan will find her eventually. He always does. Maybe. Ruth agreed. Blood was now flowing freely from her mouth, mixing with the foam that had begun to gather at the corners of her lips.

Or maybe she will disappear into a world where men like you and Duncan Fairholm have no power. Maybe she will live to be old. Maybe her child will grow up free. Maybe your entire system will collapse and be remembered only as a nightmare. Our descendants will struggle to believe was real.

Her breathing stuttered, stopped, started again with a wet, rattling sound. I die knowing I helped destroy something Duncan spent months building. What will you die knowing, Mr. Porter? That you hunted human beings for money? That you served a system designed to crush souls? that you chose cruelty when you could have chosen mercy. Ruth Chambers took one more breath.

Then she died there in the road with four slave catchers standing over her with Isaiah Mercer watching from beside his torn apart wagon with the Louisiana son beating down on a scene that would haunt James Ridley for the rest of his life. Porter stood over Ruth’s body for a full minute without speaking.

Then he turned to his men. We bury her here. We tell Duncan we intercepted the wagon, but the woman died before we could question her. We tell him Mercer claims it was the woman from the auction, but we could not verify before she died. We tell him the trail is cold. Duncan will know we failed, one of the men said.

Duncan will know exactly what happened, Porter corrected. He will know he was outmaneuvered, but he will not be able to prove it. And without proof, there is nothing he can do. They buried Ruth Chambers in a shallow grave beside the road. No marker, no ceremony, just another black body returning to Louisiana soil, one of thousands who would never be mourned publicly or remembered officially.

Isaiah Mercer watched the burial without expression. When it was finished, when the men had mounted their horses and ridden away, he stood alone beside the disturbed earth. He did not pray. He was not religious, but he spoke Ruth’s name aloud three times, as though repetition could somehow honor what she had done.

Then he continued north. As planned, he would maintain the fiction that he had been attempting to deliver Clara to free territory. He would express confusion about why she had died. He would file a report with Judge Krenshaw, claiming the property had been damaged in transit, requesting compensation for his loss. The report was denied.

Judge Krenshaw ruled that Mercer had purchased the property in ASIS condition and bore all risk. The 12-cent minimum bid was interpreted as evidence that the seller knew the property was defective. No compensation would be issued. It was in its own perverse way the perfect legal conclusion. Everyone had followed proper procedure.

All documents had been properly filed. The law had functioned exactly as designed, and yet Duncan Fairholm’s revenge had been thwarted by a dying woman and a former slave trader seeking redemption. Years later, in 1868, James Ridley experienced a religious conversion and confessed his past sins to a Methodist minister named Reverend Thomas Hargrove.

Among those confessions was a detailed account of what happened during the interception on that March afternoon in 1853. Ridley described Ruth’s final words. Described the blood on her lips and the fierce intelligence in her dying eyes. Described how she had smiled as life left her body, secure in the knowledge that she had broken Duncan Fairholm’s carefully constructed mechanism of cruelty.

I have captured over 200 fugitives in my life, Ridley told the minister. I have seen men and women beg for mercy. I have seen them fight and scream and pray, but I have never seen anyone choose death as deliberately as Ruth Chambers did. She turned her last breath into an act of defiance. She died free, even though the law said she was not, and that haunts me more than all the others combined.

Reverend Harg Grove wrote down Ridley’s confession, recognizing its historical importance, but he never published it during his lifetime. The confession sat in his personal papers until his death in 192, at which point his daughter Sarah discovered it while sorting through his effects. She was horrified, not merely by the content, though that was disturbing enough, but by the implications.

Her father had known about this incident for 34 years and had never reported it, had never shared it with historians or journalists, had simply preserved it privately as though documenting evil was sufficient without actually confronting it. Sarah Fletcher did something her father had not. She published the confession in 193 in a small abolitionist journal that few people read, but she published it.

She made it part of the public record. That publication is how we know the details of Ruth Chambers’s final moments. How we know she chose her death deliberately. How we know she smiled as she died. Secure in the knowledge that she had broken Duncan Fairholm’s plan. Duncan Fairholm spent the next 6 months searching for Claraara.

He hired professional slave catchers. He placed advertisements in newspapers across three states. He offered rewards that increased from $500 to $2,000. He never found her. Judge Krenshaw died in 1861, just before Louisiana seceded from the Union. He took whatever knowledge he had of the true circumstances to his grave.

Duncan Fairholm survived the Civil War, but lost everything in its aftermath. Bellamon was burned by Union troops in 1863. Duncan himself died in 1872 in a boarding house in Mobile, Alabama, bankrupt and alone. His wife Margaret had left him years earlier. His brother’s name was never mentioned in his presence again.

Silus Guthrie, the overseer, was found dead in 1854 in a ditch outside Greensburg. The official cause was listed as accidental drowning, though he was found face down in less than 6 in of water. No charges were ever filed. Nathaniel Puit continued as parish recorder until 1863 when he fled Louisiana ahead of Union forces.

He was never heard from again. The receipt discovered during the 1897 courthouse renovations contained more than just the record of Claraara’s sale. On the back written in William Fairhomem’s hand was a message to whoever finds this. My name is William Fairholm. I tried to save a woman I loved from my brother’s cruelty.

I failed her as I have failed in most things of importance. If you are reading this, know that the greatest evil is not the evil done by wicked men, but the evil permitted by good men who lack the courage to act. I lacked that courage when it mattered. I pray you will not. The historians who found this message understood its implications immediately.

They buried it again, sealed it back into the wall where it would remain hidden for another hundred years. The receipt was rediscovered in 1998 during another renovation. This time it was preserved. It now sits in the Louisiana State Archives, but Clara’s fate remains unknown. Some historians believe she made it to Mexico, possibly settling in Veraracruz, where a community of escaped enslaved people had established themselves.

Others think she went to Haiti. A few believe she died somewhere along the journey. One theory proposed by a genealogologist in 2006 suggests that a woman matching Claraara’s description appeared in census records in Illinois in 1870 living under the name Claraara Freeman with a mixed race daughter born in 1853. The daughter’s name was listed as Ruth.

If the theory is correct, if Claraara did survive and build a life in freedom, then Isaiah Mercer succeeded. The rescue designed to fail failed to fail. The trap Duncan so carefully constructed caught nothing. But we cannot know for certain. The historical record is incomplete. Documents were destroyed during the Civil War.

Memories were deliberately suppressed. What we are left with is fragments. a deed of sale, a receipt, a message hidden in a wall, census records that might refer to someone else entirely, and questions that will never be fully answered. Perhaps the silence of history is itself a kind of answer. Perhaps the fact that we cannot trace Claraara’s path means she successfully disappeared.

That she became impossible to follow. That she achieved what so many enslaved people dreamed of. Complete and total freedom from the system that sought to control every aspect of their existence. Or perhaps she died alone and forgotten. Another casualty of a system that destroyed millions of lives with bureaucratic efficiency.

The 12 cent transaction stands as a monument to that ambiguity. It was legal, witnessed, recorded in official documents. And yet it feels profoundly wrong in a way that transcends the already considerable wrong of slavery itself. The deliberate devaluation of a human life. The use of bureaucratic mechanisms to inflict cruelty.

the participation of judges and clerks and ordinary citizens in a transaction designed specifically to cause suffering. Everyone involved made choices. Duncan chose revenge. William chose risk, albeit too late. Isaiah Mercer chose redemption. Judge Krenshaw chose law over mercy. Ruth Chambers chose to use her death to help a stranger.

Clara chose survival, whatever that required. And the seven men who signed the deed of sale as witnesses chose to participate in something they must have known was deeply wrong. Their signatures remain on that document, preserved in archives, testimony to their complicity. Their descendants spent generations trying to bury this story, trying to ensure no one would ask uncomfortable questions about what their ancestors had done, what they had witnessed, what they had permitted.

But stories like this have a way of surfacing, of demanding to be told. This mystery shows us that the crulest weapon ever devised was not the whip or the chain, but the law itself. The system that made horror legal that allowed men to destroy lives with a signature and a handful of copper coins that permitted the sale of a pregnant woman for the price of a loaf of bread.

Not because anyone believed she was worthless, but specifically to demonstrate that worth could be assigned or revoked at will by those who held power.