It was just a family photo, but look closely at one of the children’s hands. The photograph sits in a climate controlled drawer at the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture, cataloged, but largely forgotten. It’s March 2024, and Dr. Maya Freeman, a cultural historian specializing in postreonstruction African-American communities, carefully removes it from its archival sleeve during a routine digitization project.

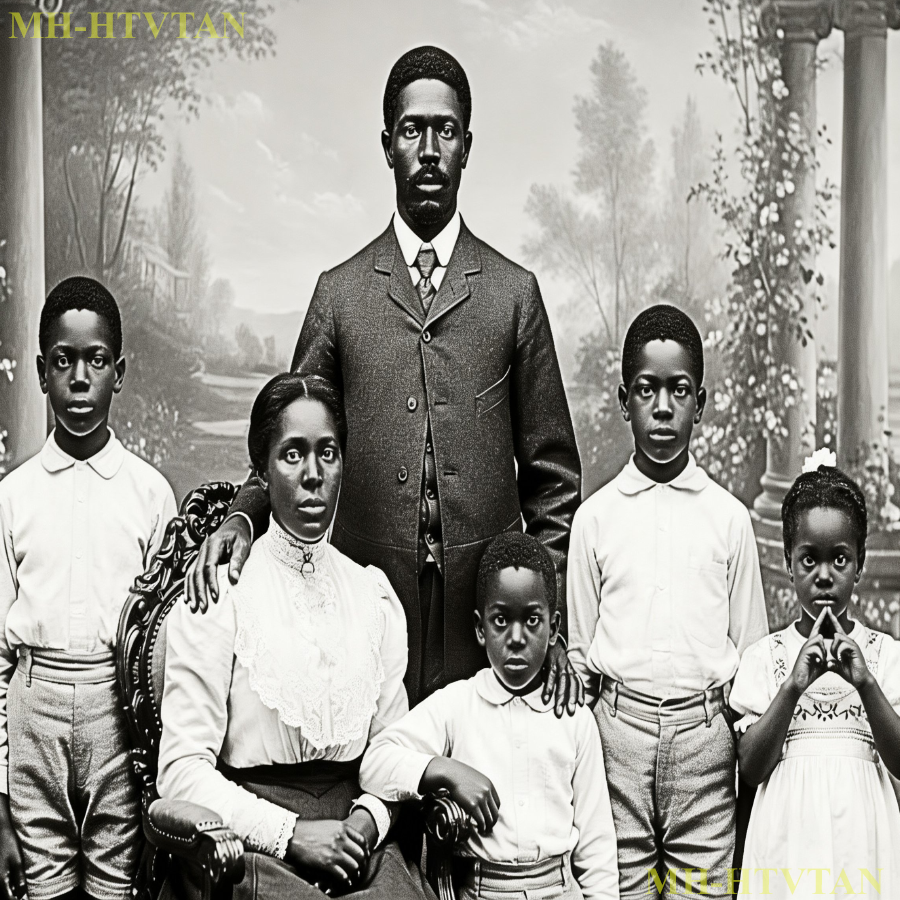

The image is remarkably preserved. A formal studio portrait from 1900 taken in sepia tones that have faded only slightly over 124 years. Six people pose with the rigid formality typical of early photography. And subjects had to remain perfectly still for long exposures. A black family.

The father stands at the back wearing a dark wool suit that looks new, perhaps his finest possession. His hand rests on his wife’s shoulder. She sits in an ornate chair wearing a high-necked dress with delicate lace at the collar, her hair pulled back severely. Four children arranged themselves around their parents. Three boys in identical knickers and white shirts with stiff collars, and a little girl, perhaps four or 5 years old, in a white cotton dress with embroidered flowers.

Maya adjusts her magnifying lens, studying each face under the bright examination light. These are people born into slavery who lived to see freedom, though what that freedom meant in 1900 Mississippi is another question entirely. The reconstruction era had ended 23 years earlier. Jim Crow laws were solidifying across the South, and black families existed in a precarious space between liberation and terror.

The father’s expression is dignified, but guarded. The mother’s face shows exhaustion beneath her composed exterior. The boys stare at the camera with unusual intensity for children, too serious, too aware. Then Maya’s eyes fall on the youngest child. The little girl stands slightly apart from her brothers, her face softer, less burdened.

But it’s her hands that make my appause. While everyone else maintains traditional poses, hands folded, clasped behind backs, or resting naturally, the girl’s left hand is positioned deliberately against her small chest, forming a specific gesture, three fingers extended upward, the index and middle finger crossed tightly over the thumb.

Maya leans closer, her breath catching. The gesture is too precise to be accidental, too intentional for a child’s random fidgeting during a long exposure. She photographs the detail with her highresolution camera, zooming in on those tiny crossed fingers. The studio backdrop, painted garden scenery with artificial columns, suddenly feels less like decoration and more like a stage set, concealing something deeper.

What were they hiding? What did this family know that required speaking in codes, even in what should have been a documented public moment? Maya checks the museum’s acquisition records. The photograph was donated in 1987 from an estate in Chicago, part of a larger collection of early African-American portraiture.

No names were recorded with the image, no provenence beyond Mississippi family circa 1900. Just six faces frozen in time and one small hand making a signal that shouldn’t exist in 1900, 35 years after the Underground Railroad supposedly ceased operations with the end of the Civil War. Maya feels the familiar electricity that comes with discovering something extraordinary hidden in plain sight.

She prints an enlargement and pins it to her office corkboard. The investigation begins now. Maya spends 5 days consumed by the photograph. Barely sleeping, she surrounds her office with research materials, maps of Mississippi from 1900, census records, histories of reconstruction, and its violent collapse.

Scholarly texts on African-American survival strategies in the post-slavery South. The little girl’s hand gesture haunts her. Those three crossed fingers feel significant, deliberate, but nothing in her extensive knowledge base matches it. She starts methodically, searching academic databases for documented hand signals and coded communication systems used by enslaved people and their descendants.

She finds references to quilt patterns allegedly used on the Underground Railroad, songs with double meanings and verbal codes, but no hand signals matching what she sees in the photograph. On the sixth morning, Maya contacts Dr. Elliot Richardson, an elderly historian at Howard University who spent 45 years studying covert resistance networks among black communities from slavery through Jim Crow.

She emails him highresolution images of the child’s hand. His response arrives within 2 hours, marked urgent. This changes everything I thought I knew. Call me immediately. Maya’s hands shake slightly as she dials. Elliot’s voice trembles with barely contained excitement. Where did you find this photograph? Smithsonian Archives, donated in 1987. No identification.

Mississippi 1900. Why? What am I looking at? Maya, I need you to understandsomething. Elliot pauses, gathering his thoughts. The Underground Railroad didn’t end in 1865. That’s the sanitized version we teach in schools. Slavery ended. The railroad shut down. Everyone lived happily ever after. But the reality was far more complex and far more dangerous.

Maya grabs her notebook, pen poised. Explain. After reconstruction collapsed in 1877, the South became a killing ground for black people. lynchings, night riders, systematic economic exploitation, legal persecution under Jim Crow. Black families needed protection networks just as desperately as they had during slavery, maybe more so, because now they were supposedly free but had no federal protection. So, the networks continued.

They evolved. Elliot corrects, “The original underground railroad conductors and station masters, those who survived, adapted their systems. They created new codes, new safe houseses, new routes to help black families escape racial violence, arrange safe passage to northern cities, warn each other about threats.

These networks operated in absolute secrecy from roughly 1877 through the 1920s. Maya stares at the photograph pinned to her wall. And the hand signal, that’s what shocks me. I’ve read oral histories, studied coded letters, interviewed descendants of network families. I’ve heard rumors of hand signals for decades. Whispers, fragmented stories, but I’ve never seen photographic evidence. His voice drops.

What you’re looking at is called the reload signal. It meant a family was connected, prepared, and ready to help or receive help. It was deliberately taught to children. Why children? Because children could move through communities without attracting suspicion. And if parents were killed or arrested, the children needed a way to identify safe families who would protect them.

Maya feels chills run down her spine, staring at the little girl in her white dress, holding a gesture that meant her parents had prepared her for their possible death. Maya needs to find the photographer’s studio, the starting point of this family’s story. The photograph bears a faint stamp on the reverse side, partially degraded, but still legible under magnification.

Sterling and son’s photography, Nachez miss. She spends two days researching Nachez, Mississippi in 1900. The city sits on the Mississippi River, once a major hub of the cotton trade and slave auctions, now a Jim Crow stronghold where black families navigate daily violence and oppression.

She discovers that Sterling and Sons operated from 1892 to 1911, one of the few photography studios in the South that served black clientele. Maya tracks down census records, city directories, and newspaper archives. [music] She finds an obituary from 1928 for Marcus Sterling, the studio’s founder, describing him as a respected colored businessman who served the community with dignity for 30 years.

The obituary mentions his son, James Sterling, who continued operating a smaller portrait business in Chicago after leaving Mississippi in 1911. Following the thread to Chicago, Mia discovers that James Sterling’s great-granddaughter, Vanessa Sterling Hughes, is a retired art teacher living on the city’s southside.

Maya sends a carefully worded email explaining her research, attaching a scan of the photograph’s backstamp. Vanessa responds within hours. My great-grandfather rarely spoke about Mississippi, but he kept things. Come see me. 3 days later, Ma sits in Vanessa’s living room surrounded by family photographs spanning five generations.

Vanessa, a woman in her 70s with silver locks and warm eyes, brings out a wooden trunk that belonged to James Sterling. He carried this trunk from Mississippi to Chicago in 1911. Vanessa explains, “Never let anyone look inside while he was alive.” After he died, my grandmother inherited it, but didn’t know what to make of the contents.

Now you’re the first historian to see this. Inside the trunk, hundreds of glass plate negatives, carefully wrapped and preserved. Portraits of black families from Nachez between 1892 and 1911. And beneath the negatives, three leatherbound journals in James Sterling’s handwriting. Vanessa opens the first journal.

My great-grandfather wrote everything down. every family who came to the studio. Dates, names, sometimes notes about why they needed portraits made. Maya’s heart races as Vanessa flips through pages to September 1900. Her finger stops at an entry dated September 14th. Coleman family, six portraits, express order, 3-day rush, special arrangement.

Coleman, Maya whispers, what does special arrangement mean? Vanessa looks at her with inherited knowledge in her eyes. My great-grandfather’s studio wasn’t just a business. It was a safe place, a checkpoint. Families who needed help knew they could come to him. Was he part of the network? He never called it by name, not even in his journals.

But yes, he documented people who were about to disappear by choice to survive. This photograph you found, those peopleneeded evidence they existed before they vanished into a new life somewhere safer. Maya stares at the journal entry. The Coleman family, six people, one little girl making a signal that would outlive them all.

Do you have the glass plate negative for this portrait? Maya asks. Vanessa smiles slightly. I think I can find it. Vanessa carefully lifts a wooden box from the trunk, handling it with reverence. Inside, wrapped in yellowed cloth, are glass plate negatives organized chronologically. She moves through them methodically until she finds September 1900.

Here, she says softly, holding up a glass plate to the light. Maya sees the image in negative, dark figures against a light background, but unmistakably the same family. the father’s protective stance, the mother’s formal posture, the three boys, and the little girl with her hand positioned in that deliberate gesture.

“Can we have this professionally scanned?” Maya asks. The high resolution might reveal details the paper print doesn’t show. I know someone at the Art Institute who specializes in historic photographic preservation, Vanessa says. “Let me make a call.” Two days later, Maya stands in a conservation lab at the Art Institute of Chicago as a specialist named Robert carefully positions the glass plate under a highresolution scanner designed specifically for historic photographic materials.

The resulting digital image is stunningly clear. Every texture of fabric, every strand of hair, every line in the subject’s face is rendered in remarkable detail. Robert zooms in on the little girl’s hand. That’s definitely intentional, he confirms. See how her fingers are positioned with tension? She’s holding that gesture deliberately, probably for the entire exposure time.

That would have been difficult for a child this young. Exposures in 1900 took several seconds of absolute stillness. She was trained, Maya says quietly. Robert points to another detail. Look at the mother’s left hand resting in her lap. See this ring on her middle finger? It has an engraving. Maya leans closer. The ring bears a tiny symbol.

Three interlocking circles forming a triangle. What does that mean? Vanessa asks. Maya photographs the detail, her mind racing. I don’t know yet, but it’s connected somehow. Back at Vanessa’s home, they examine James Sterling’s journals more carefully. Maya discovers that certain families have small symbols marked next to their names: stars, circles, triangles.

The Coleman family entry has three interlocking circles drawn in the margin. He was marking network families. Maya realizes different symbols meant different things. Maybe levels of involvement or types of assistance needed. Vanessa flips through more pages. Look at this. August 1900, one month before the Coleman’s, a Reverend Patterson visited, discussed arrangements for autumn departures.

12 families confirmed. 12 families preparing to leave Mississippi, Maya says. The Coleman’s were part of a larger exodus. But why? Vanessa asks. Well, what happened in Nachez in 1900 that made families run? Maya pulls out her laptop and begins searching historical records. Within minutes, she finds it.

Newspaper articles from the Nachez Democrat. August through October 1900. A wave of racial violence following a disputed land claim. Three black land owners lynched. Churches burned. Families terrorized. The September 14th portrait of the Coleman family was taken at the height of the violence. They were documenting themselves before they disappeared.

Maya says this photograph was evidence of their existence, their dignity, their family preserved before they had to erase themselves to survive. Vanessa touches the journal gently. and my great-grandfather helped them do it. Maya immerses herself in Nachez records from late 1900, piecing together a picture of systematic terror, she discovers that the violence wasn’t random.

It targeted black families who had managed to acquire land, establish businesses, or gain any measure of economic independence in the 35 years since emancipation. The Coleman family, she learns from property records, owned 40 acres of farmland outside Nachas, purchased in 1892. The father, Isaac Coleman, had been born enslaved in 1861, freed as an infant, and somehow managed to save enough money to buy land.

An [music] extraordinary achievement that made him a target. She finds Isaac’s name in an 1899 agricultural report as one of the few black farmers successfully growing cotton and vegetables for market. Success that would have bred resentment among white land owners accustomed to black subservience and economic dependence.

Then in October 1900, a notice in the Natchez Democrat land auction. Coleman property, 40 acres, forfeited for unpaid [music] taxes. A legal theft disguised as bureaucracy. But by then, the Coleman’s were gone. Maya contacts Dr. Richardson again, sharing everything she’s discovered. He guides her to census records, the paper trail that might track the family’s movement.

Ifthey left Mississippi in late 1900, they would have headed north, Elliot explains. Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, [music] cities where black communities were establishing themselves, where factory work was available, where they might disappear into growing populations. Maya searches 1910 census records for northern cities, looking for Isaac Coleman and his family.

The name is too common, appearing hundreds of times. She needs more specific identifiers, and she remembers the children, the three boys and the little girl. She estimates their ages from the photograph. The oldest boy perhaps 12, the middle boy 10, the youngest boy seven, and the girl about four or five.

She searches for black families in northern cities with four children matching those age ranges. The work is painstaking, taking days of cross- referencing city directories, church records, and school enrollment lists. Finally, in a 1910 census record from Detroit, Michigan, she finds them. Isaac Coleman, age 49, labor. his wife Esther age 44ress children Thomas 22, Benjamin 20, Samuel 17, and Ruth 14.

The ages fit perfectly, accounting for 10 years of growth. The Coleman’s made it. They survived. But Maya notices something else in the census record. Under year of immigration to Michigan, it lists 1900 under place of birth for all family members, Mississippi. And in the margin, in the census takers handwriting, a small notation, family declined to provide prior address.

They had buried their past deliberately, erasing Nachez [music] from their story, protecting themselves even a decade later and hundreds of miles away. Maya stares at Ruth’s name, the little girl in the white dress, who made the reload signal with her small hand, who carried a code meant to save her life.

She’s determined to find out what happened to Ruth Coleman. Tracking Ruth Coleman through 114 years proves extraordinarily difficult. Maya starts with Detroit Records from 1910 onward. Searching for a black woman born in Mississippi around 1895 or 1896. She finds Ruth’s name in 1918 Detroit School Records.

Graduating from Cass Technical High School, one of the few black students in her class. Then the trail goes cold for several years until Maya discovers a marriage certificate from 1921. Ruth Coleman married to William Harris, a postal worker. The surname change complicates the search, but Maya persists. She tracks Ruth Harris through city directories, living on Detroit’s east side.

No occupation listed in the 1920s and 1930s, likely working at home, raising [music] children, taking in laundry, or doing domestic work that left no official record. Then Maya finds something unexpected. Ruth’s name appears in the archives of the Second Baptist Church of Detroit, one of the oldest black churches in the city and a historic station on the original Underground Railroad before the Civil War.

Ruth served as a Sunday school teacher from 1925 to 1964. [music] Maya contacts the church, speaking with the current historian, an elderly deacon named Frank Morrison, who maintains their extensive archives. When she explains her research, his response surprises her. Mrs. Harris, he says immediately. Oh, I remember Sister Ruth. She taught my Sunday school class when I was a boy in the 1950s.

Quiet woman, very dignified, but warm with children. She died in 1987, lived to be 91 years old. Maya’s heart races. Did she ever talk about Mississippi, about her childhood? Never, not once. A lot of the older folks who came up from the South during that era didn’t speak about it. Too much pain, too many memories they wanted to leave buried.

Did she have children? Three daughters and a son. The youngest daughter, Grace, still lives here in Detroit. Works as a nurse at Henry Ford Hospital. I can give you her number if you’d like. That evening, Maya calls Grace Harris Thompson, Ruth’s daughter, now 72 years old. Grace is cautious at first, another historian asking about the past.

But when Mia mentions the photograph and describes the hand signal, Grace’s voice breaks. I need to see that picture, she says. Can you send it to me right now? Maya emails the highresolution scan. 10 minutes pass. Then her phone rings. Grace is crying. That’s my mother. That little girl is my mother. I’ve never seen a photograph of her as a child.

She always said they didn’t have any pictures from before they came to Detroit. She said they were lost. They weren’t lost. Maas says gently. They were hidden, protected. The hand signal, Grace whispers. My mother did that once. I was maybe 8 years old and we were at church. An old woman came up to her. Someone visiting from down south and they looked at each other and my mother made that exact gesture with her hand.

The woman started crying and they hugged like they were family, but I’d never seen her before. When I asked my mother about it later, she just said, “That’s how we used to say hello in the old days, baby.” Grace agrees to meet Maya in Detroit. They sit in Grace’s livingroom, surrounded by photographs of Ruth’s life, her wedding picture from 1921, images of her teaching Sunday school, family gatherings from the 1940s through the 1980s, but nothing from before 1910, nothing from Mississippi.

My mother was a woman of silences, Grace explains. She loved us fiercely, but there were rooms inside her we were never allowed to enter. Whenever we asked about her childhood, she’d say, “That was another life, baby. This is the life that matters now.” Grace brings out a wooden box she inherited when Ruth died.

After she passed, I found this hidden in the back of her closet. I never knew what to make of it. Inside the box, a small leatherbound Bible from 1892. The pages worn and annotated in careful handwriting. A cotton handkerchief embroidered with the initials EC. Esther Coleman, Ruth’s mother, three buttons that look handcarved from wood, and a folded piece of paper yellowed with age.

Maya carefully unfolds the paper. It’s a hand-drawn map, crude but detailed, showing roads, rivers, and landmarks. Notations in pencil marked distances. 12 mi to Jackson. Safe house, barn with red door. Avoid main road after dark. This is an escape route, Maya says, her voice hushed.

This is how your family fled Mississippi. Grace stares at the map, seeing her mother’s history made tangible. She carried this her whole life. Never showed anyone, never spoke about it, but she kept it. Maya photographs the map, documenting every detail. Then she notices something else in the box, a small piece of folded cloth.

When she opens it, she finds a child’s white dress yellowed with time with embroidered flowers along the hem. Grace’s hand trembles as she touches it. The dress from the photograph. Your mother kept it. Maya says she kept the evidence. Over the next hour, Grace shares fragments of stories Ruth told over the years. Never complete narratives, just pieces that Grace is now assembling into a fuller picture.

Ruth had two older brothers and one younger brother. Thomas, the oldest, became a factory foreman in Detroit. Benjamin worked for the railroad. Samuel died young in 1925 from tuberculosis. Ruth’s father, Isaac, worked in an automobile factory until his death in 1933. Her mother, Esther, took in laundry and raised her grandchildren, living until 1941.

They never went back to Mississippi, Grace says. Not once, not even to visit. My grandfather used to say that ground is soaked with too much blood. I’ll never set foot there again. Did your mother ever explain the hand signal? What it meant? Grace thinks carefully. Once near the end of her life, I asked her directly.

She was in her 80s and I thought maybe she’d finally tell me. She looked at me with these sad ancient eyes and said it meant we took care of each other when nobody else would. It meant family wasn’t just blood. It was anybody willing to risk everything to keep you alive. With Grace’s permission, Maya begins interviewing Ruth’s surviving relatives and the descendants of families who knew the Coleman’s in Detroit.

What emerges is a portrait of a vast, invisible network that extended far beyond Mississippi. She speaks with Thomas Coleman’s grandson, Marcus, now 75, who shares stories passed down from his grandfather about the journey north in 1900. Grandpa Thomas was 12 years old when they left Nachez. Marcus explains, “He said they traveled at night, mostly, moving from safe house to safe house.

Sometimes they’d stay in a barn, sometimes in the back room of a church, sometimes in the home of a black family they’d never met [music] before. But everyone knew the signals. Everyone knew how to help. The reload signal, that and others. Grandpa said there were different hand signs for different messages.

Danger ahead, safe to stay, keep moving, children present. They were taught these signals as young children, practiced them like learning letters and numbers. It was survival education. Maya learns that the network operated with remarkable sophistication. Station masters, families who provided safe houses, were positioned along routes leading north.

Messages traveled through coded letters, trusted messengers, and sometimes through songs sung at church gatherings that contained hidden meanings. She discovers that Second Baptist Church in Detroit, where Ruth taught Sunday school for 40 years, was itself a network hub. The church had been a terminal station on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, [music] and it quietly continued that role after reconstruction collapsed.

Reverend James Carter, the church’s current pastor, gives my access to historical records usually kept private. Our predecessors understood that the struggle didn’t end in 1865. He explains, “They maintained safe house networks, employment assistance, legal aid, all underground, all unrecorded, because official channels offered black people no protection.

” Amaya finds coded entries in church ledgers from 1895 to 1920. Families joining the congregationfrom Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, always in groups, always arriving in autumn or winter when travel was hardest, but also when white authorities paid less attention. Your ancestor Ruth, Reverend Carter says to Grace, was part of something extraordinary.

These people built their own nation within a nation, their own system of mutual aid and protection that ran parallel to and hidden from white society. Maya contacts Dr. Richardson again sharing her discoveries. He connects her with other historians researching similar networks in different regions. Together they begin mapping an underground infrastructure that spanned the entire south and extended into northern cities.

Dozens of interconnected communities communicating through codes protecting each other across state lines. This rewrites our understanding of the post reconstruction era. Elliot tells her, “We thought black people were simply victims passively enduring violence. But they were agents of their own survival, building sophisticated resistance networks that operated successfully for decades.

Maya organizes a gathering in Detroit for September 2024, bringing together descendants of the Coleman family and other network families who fled Mississippi around 1900. She partners with Second Baptist Church and the Charles H. Wright Museum of African-American History to host the event. 43 people come, children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of families who survived through coded signals and mutual protection.

Many have never met, their families scattered across Michigan, Illinois, Ohio, and Pennsylvania by more than a century of migration and change. Grace stands before the assembled group, now seeing her mother’s story as part of something much larger. Marcus is there, representing Thomas Coleman’s line. A woman named Patricia represents Benjamin Coleman’s descendants.

Samuel’s early death left no children, but his memory is honored. Maya has prepared a presentation, but as she stands before these families, she realizes the academic research is secondary. The real story lives in the faces surrounding her. People who exist because their great great-grandparents knew how to read a hand signal in the dark.

She projects the photograph large on the screen. Isaac and Esther Coleman, their three sons, and little Ruth in her white dress, her hand making the gesture that saved her life. The signal, the reload signal, was a language of survival. Ma explains, “Your ancestors created communication systems that kept communities alive when law, government, and society all abandoned them.

This wasn’t just resistance. This was genius. This was love made into strategy. An elderly man in the front row raises his hand. His [music] name is James, and his great-grandmother ran a safe house in Alabama. My great-grandmother never told her children about this work. She was terrified, even decades later, that speaking about it would put someone in danger.

Why did they stay silent for so long? Grace answers, “Because trauma doesn’t end when the danger ends. Because they wanted us to have lives without fear. Because speaking about survival sometimes means reliving what you survived.” She pauses, her voice strengthening. But silence has a cost, too. It means the brilliance gets forgotten.

The courage gets erased, and the children never understand what it took for them to exist. Marcus adds, “We’re telling these stories now while we still can. While people who remember are still alive, the museum curator approaches my afterward. We want to create a permanent exhibition. Not just about the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, but about these post reconstruction networks.

We want your research to anchor it.” Maya looks at the photograph of Ruth Coleman one more time, four years old, wearing her best dress, holding a signal that would echo across 124 years. Yes, she says it’s time these stories were told. The Charles H. Wright Museum of African-American History opens its new permanent exhibition in February 2025.

Hidden Signals: Networks of Survival After Emancipation. The Coleman Family Photograph anchors the central gallery. Ruth’s hand signal enlarged and explained. No longer a mystery, but a testament to collective brilliance and resistance. Maya’s research expands beyond Mississippi and Michigan. She identifies similar coded systems in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee, entire invisible infrastructures of mutual protection that operated outside historical record.

Other historians begin investigating their own regions, discovering parallel networks their scholarship had previously missed. Academic journals publish MA’s findings. Documentary filmmakers request interviews. But the most meaningful impact happens quietly in living rooms and church basements where descendants gather to share stories their grandparents never told.

Grace establishes a scholarship fund in Ruth’s name for students studying African-American history and socialjustice. She works with the museum to create educational programs teaching young people about the networks not as ancient history but as models of community organizing and mutual aid that remain relevant today.

The wooden box that held Ruth’s Bible, map, and childhood dress becomes part of the museum’s permanent collection, displayed alongside James Sterling’s journals and glass plate negatives. Visitors can see the actual artifacts that made survival possible. Handdrawn maps, coded letters, photographs that documented existence before families had to disappear.

Families separated by generations reconnect. A woman in Chicago discovers her cousins in Cleveland. A man in Philadelphia learns his great aunt’s family settled in Detroit. The network dormant for a century sparks back to life. Not from necessity now, but from love and remembrance and the need to honor those who came before.

Maya returns to the Smithsonian where this journey began and requests they update their records for the Coleman family photograph. [music] No longer cataloged as unknown family circa 1900. It now reads Isaac and Esther Coleman family Nachez, Mississippi, September 1900. Photograph taken by James Sterling 3 weeks before family fled racial violence.

Child making reload signal is Ruth Coleman. Later Ruth Harris, 1896 to 1987, who became a Sunday school teacher in Detroit and quietly preserved this history for 124 years. She thinks about how many other photographs in archives worldwide hide similar stories. How many hand signals, glances, and silent codes wait for someone to ask the right questions.

She commits herself to finding them. The photograph remains in Maya’s office, too, a copy pinned to her corkboard. She looks at it every morning. Isaac’s protective stance, Esther’s composed strength, the three boys awareness beyond their years, and Ruth, small and bright, in her white dress, holding in her hand a secret that outlived everyone who knew its original meaning.

Outside, Detroit moves through another February morning. Children walk to school. People head to work. The city has changed, transformed by the very migrations that Isaac and Esther and thousands like them made possible. The photograph stays eternal, but now everyone knows what it means. Now, everyone knows that when you look closely at the little girl’s hand, you’re not seeing a child’s random gesture.

You’re seeing survival coded into three crossed fingers. You’re seeing resistance so sophisticated it remained invisible for over a century. You’re seeing proof that love, when organized and strategic, can protect generations not yet born. The network that began in slavery, evolved through reconstruction’s collapse, and extended into the 20th century, finally has its recognition.

Not because it was written in official records, but because it was written on the body in hand signals passed from parent to child and gestures held steady during long photographic exposures in silence that protected until silence was no longer necessary. Ruth Coleman kept the white dress for 91 years. She never wore it again after that photograph, but she kept it wrapped carefully in cloth hidden in the back of her closet, a silent witness to what survival looked like in 1900 Mississippi.