In the oppressive heat of Bellman Plantation, South Carolina 1008 151, a secret existed that violated every boundary of human decency and medical ethics. Behind the locked doors of the master’s private study, a person named Jordan was kept hidden from the outside world, examined, exploited, and shared between husband and wife in ways that defied both nature and morality.

Jordan had been born with a condition that 19th century medicine called hermaphroditism, possessing physical characteristics of both male and female. When Master Richard Belmont discovered this anomaly among his enslaved people, he and his wife Elellaner became consumed by an obsession so dark that when the truth finally emerged, it would destroy their family and expose one of the most disturbing dimensions of slavery’s complete ownership of human bodies.

Jordan was born in 1,833 on a small tobacco farm in North Carolina. Delivered by a midwife who immediately recognized that something was different about this infant, the baby possessed ambiguous genitalia characteristics that made immediate gender assignment impossible. In an era when such conditions were barely understood by medical science and considered either divine curse or demonic possession by common people, Jordan’s very existence presented an impossible problem.

The midwife, a enslaved woman named Mama Ruth, who had delivered hundreds of babies, made a decision that would shape Jordan’s entire life. She declared the baby female, named her Jordan after the river where Moses had been found, and told the mother to raise the child as a girl. It was the kindest option available, giving Jordan at least the possibility of a normal life within the constrained world of slavery.

For the first 15 years, Jordan lived as a girl, working in the tobacco fields alongside other enslaved children, wearing dresses made from rough cloth, learning the skills expected of enslaved women, Jordan’s body developed in ways that confused everyone, growing tall and muscular like the boys, developing a deeper voice than other girls, but also showing subtle curves and features that seemed feminine.

The other enslaved people whispered about Jordan’s difference, but protected the secret, understanding that being different in any way made enslaved people vulnerable to exploitation. In 1,848, when Jordan was 15, the tobacco farm was sold and all enslaved people were auctioned to settle debts. Jordan stood on the auction block in Wilmington, tall and unusual, looking, drawing curious stares from potential buyers.

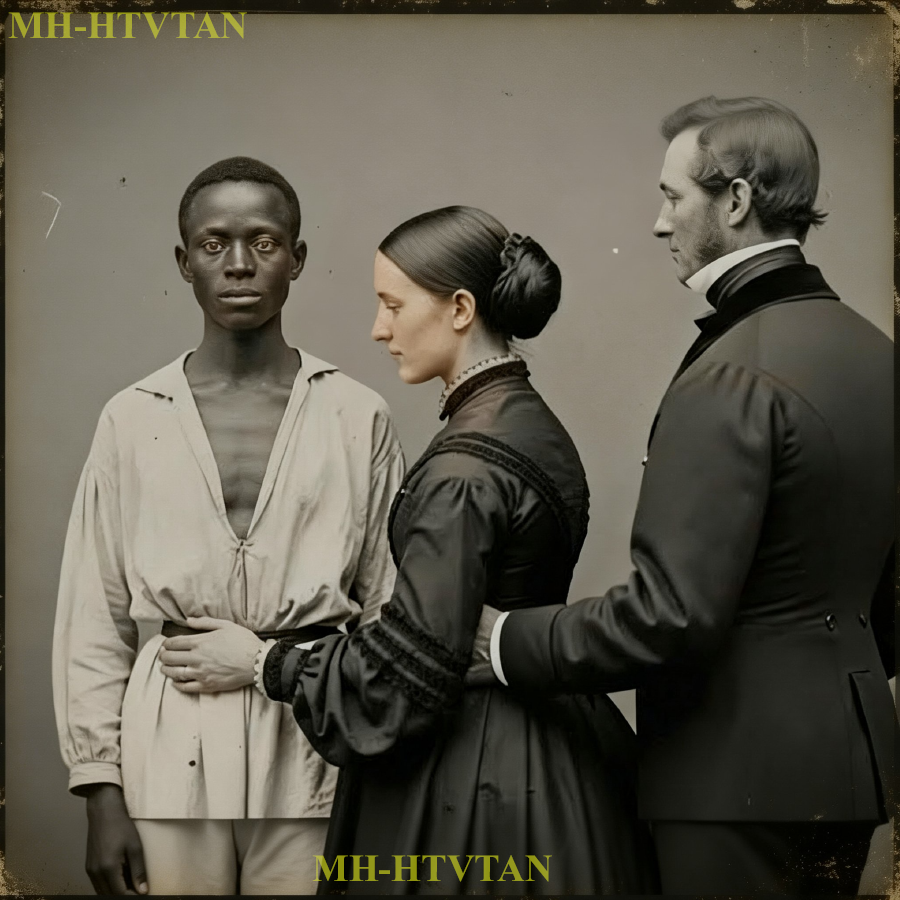

Most plantation owners passed by, unsettled by Jordan’s ambiguous appearance. But one man studied Jordan with intense interest that went beyond typical slave buying assessment. Richard Belmont was 42 years old, owner of Belmont Plantation with 300 acres of prime South Carolina cotton land and 80 enslaved people.

He was also an amateur medical enthusiast obsessed with natural philosophy and human anatomy. He collected medical texts, performed amateur dissections on animals, and fancied himself a scientist despite having no formal training. When he saw Jordan on that auction block, he recognized immediately that this was no ordinary slave, but a medical curiosity that could satisfy his intellectual obsessions.

Belmont purchased Jordan for an unusually high price, raising eyebrows among other buyers, who could not understand why anyone would pay premium rates for such an odd-looking slave. He transported Jordan to Belmont Plantation, not to work the fields, but to live in a small room adjacent to his private study, a space he had converted into a makeshift medical examination room.

The first examination occurred within hours of Jordan’s arrival. Belmont ordered Jordan to undress completely while he took detailed notes, measurements, and sketches of Jordan’s body. He documented every detail of Jordan’s anatomy, treating the terrified teenager as a specimen rather than a human being. Jordan had no choice but to submit, understanding that resistance would result in punishment or death.

But Richard Belmont was not the only person who would become obsessed with Jordan’s unique body. His wife, Ila Lanner, 38 years old and trapped in a loveless marriage, discovered Jordan’s presence within days of the arrival at Belmont Plantation. Elina had her own reasons for interest in Jordan, reasons that mixed curiosity with suppressed desires she had never been allowed to acknowledge or explore.

Elina Belmont had been raised in Charleston’s strict society, married at 18 to a man chosen by her father, taught that her role was to be decorative, silent, and endlessly submissive. She had given Richard three children, but had never experienced passion or genuine intimacy in her marriage. Richard was cold, clinical, more interested in his books and specimens than in his wife.

Elaner lived in a prison of silk and propriety, her own desires so deeply buried she barely acknowledged they existed. When Elaner first saw Jordan, something awakened in her that she had never felt before. Jordan was beautiful in a way that transcended conventional categories, possessing features that were both masculine and feminine, strong yet delicate, confusing yet compelling.

Elellaner found herself making excuses to visit Richard’s study when she knew Jordan would be there watching from doorways. Finding reasons to interact with this mysterious person who seemed to exist outside all normal classifications, Richard noticed his wife’s interest, and in a decision that revealed the depth of his moral corruption, decided to include Elina in his research.

He framed it as educational, telling Illaner that Jordan represented a rare medical phenomenon that they both should study. But Richard’s motivations were darker than simple education. He had become sexually aroused by his examinations of Jordan, and he recognized similar attraction in his wife.

The idea of sharing Jordan, of using this enslaved person’s unique body to fulfill both their desires, excited him in ways that normal marital relations never had. The arrangement that developed over the following months was one of the most disturbing examples of slavery’s complete objectification of human beings. Jordan became a shared possession between husband and wife.

examined, touched, and used by both in ways that served their obsessions, while completely disregarding Jordan’s humanity, autonomy, or suffering. Richard would summon Jordan to his study during the day, conducting what he called medical examinations that became increasingly invasive and sexual. He documented everything in detailed journals, sketching Jordan’s body from every angle, taking measurements that had no scientific purpose, touching in ways that were clearly for his own gratification rather than legitimate

research. Elener would visit Jordan’s small room at night, ostensibly to bring food or check on the slave’s wellbeing, but actually to satisfy her own confused desires. Elaner’s interactions with Jordan were different from Richard’s clinical exploitation. Eliner was gentler, more emotional, seeking something that resembled intimacy, even though true intimacy was impossible given the absolute power imbalance between them.

Jordan endured this dual exploitation in silence, trapped between two people whose obsessions fed off each other. Jordan could not speak of what was happening, could not resist without facing brutal punishment, could not escape the small room that had become a prison. The only survival strategy available was dissociation, separating mind from body, enduring what could not be prevented.

But the situation was unsustainable. Richard’s obsession deepened to the point where he neglected plantation management, spending hours in his study with Jordan while crops failed and enslaved people went unsupervised. Elellaner’s attachment to Jordan grew dangerously emotional, creating jealousy when she knew Richard was with Jordan, leading to arguments between husband and wife that the household staff could not help but overhear.

The enslaved community at Belmont watched these developments with growing concern. They understood that Jordan was being exploited in ways that went beyond normal plantation abuse. Though the specific details remained unknown, some tried to reach out to Jordan during the rare moments when Jordan was allowed outside the study, offering sympathy and support.

But Jordan had become so traumatized by the situation that communication was nearly impossible. The breaking point came in the spring of 1008 151 when both Richard and Elener’s obsessions reached a crisis simultaneously. Richard had become convinced that Jordan’s unique anatomy held secrets that could advance medical science. and he began planning to perform a surgical examination that would likely kill Jordan in the process.

Elena, meanwhile, had developed such emotional attachment to Jordan that she began planning to run away with Jordan to the north, a fantasy that revealed how completely she had lost touch with reality. The confrontation occurred when Elener discovered Richard’s surgical plans. She burst into his study while he was preparing instruments.

Found Jordan restrained on an examination table and realized that Richard intended to dissect Jordan while still alive to study the internal organs. Elaner’s rage erupted in ways that shocked everyone who knew the normally docsil southern lady. You will not kill Jordan. Elellaner screamed, grabbing the surgical instruments from Richard’s hands. Jordan is not your specimen.

Jordan is a human being. Richard’s response revealed the depth of his madness. Jordan is property, my property. I can do whatever I wish with my property, including advancing science through anatomical study. The argument escalated into physical violence with a leaner attacking Richard, trying to free Jordan from the restraints, while Richard struggled to restrain both his wife and his intended victim.

The commotion drew house slaves who witnessed the scene with horror. Seeing the master and mistress fighting over the terrified person on the examination table. In the chaos, Jordan managed to break free from the restraints and flee the study. Despite having no plan and no resources, Jordan ran into the South Carolina wilderness, choosing the uncertainty of escape over the certainty of death on Richard’s examination table.

Jordan’s escape triggered a massive manhunt. Richard offered enormous rewards for Jordan’s capture. Not because of the monetary value of losing one enslaved person, but because his obsession demanded Jordan’s return. Elener, meanwhile, secretly aided Jordan’s escape, leaving supplies at predetermined locations and passing information about patrol routes to enslaved people who might encounter the fugitive.

But Jordan was never recaptured. Whether Jordan successfully reached the north, found refuge in remote wilderness, or died during the escape attempt remains unknown. What is certain is that Jordan disappeared from all historical records after fleeing Belmont Plantation in May 1008 151. The aftermath of Jordan’s escape destroyed the Belmont family, Richard descended into complete madness.

Obsessed with recovering his lost specimen, spending a fortune on slave catchers who found no trace of Jordan. His plantation fell into ruin as he neglected all management to focus on his feudal search. He died in 1,854, broken financially and mentally. His scientific pretensions exposed as the madness they always were.

Elleaner’s fate was equally tragic. Her open sympathy for Jordan and her violent confrontation with Richard destroyed her reputation in Charleston society. Her own family disounded her. Unable to accept that she had chosen an enslaved person over her husband, she was quietly institutionalized in a private asylum where she spent the remaining years of her life writing obsessive letters to Jordan.

Letters that were never sent because there was no address to send them to. The three Belmont children were raised by relatives who erased all mention of Jordan from family histories, burning Richard’s medical journals and Elanor’s letters, trying to bury the scandal that had destroyed their parents. For over a century, the true story of what had happened at Belmont Plantation remained a closely guarded family secret.

In 1967, a historian researching Interrex conditions in the 19th century discovered a brief mention of the Heraphrodite slave of Belmont in a Charleston doctor’s correspondence. This single reference led to years of investigation that eventually uncovered sealed medical records, surviving fragments of Richard’s journals, and testimony from descendants of Belmont’s enslaved community.

The oral histories preserved in the Africanameanian community told a different version of Jordan’s story than the official records. They described Jordan not as a passive victim, but as someone who had maintained dignity and humanity despite unspeakable exploitation. They claimed Jordan had successfully escaped, had lived as a free person in Canada, and had even married and adopted children.

Though none of this could be definitively verified, modern medical understanding recognizes that Jordan was likely born with an interex condition, possibly congenital adrenal hyperlasia or androgen insensitivity syndrome, conditions that result in ambiguous genitalia and development of both male and female characteristics.

In Jordan’s era, such conditions were barely understood and often considered monstrous or demonic. People born with interrex conditions faced medical exploitation, social ostracism, and violence. Jordan’s story became particularly significant in the 1990s when scholars began examining the intersection of disability, medical exploitation, and slavery.

The case demonstrated how enslaved people with any physical difference faced heightened vulnerability to dehumanization and abuse. It also revealed that sexual exploitation in slavery operated in more complex ways than simple male master female slave dynamics, that obsession could transcend conventional categories, and that both men and women could be perpetrators.

The feminist analysis of Elanor’s role proved particularly controversial. Some historians argued she was as much a victim as Jordan, trapped in a patriarchal system that gave her no acceptable outlet for her desires and pushed her into exploitation as her only form of agency. Others countered that Elina’s victim status did not excuse her participation in Jordan’s abuse, that she could have chosen not to exploit her power over an enslaved person regardless of her own oppression.

In 2003, Interx rights activists adopted Jordan’s story as a historical example of medical exploitation of Interrex people, drawing parallels to modern non-constentual surgeries on Interex infants. They argued that Jordan’s forced examinations and Richard’s planned dissection represented the same medical objectification that Interrex people continued to face, though in less extreme forms.

Descendants of Belmont’s enslaved community held a ceremony in 2010 at the plantation site, now a historical landmark. They honored Jordan’s memory, acknowledged the unique vulnerabilities faced by enslaved people with interrex conditions, and called for greater recognition of how disability and difference intersected with slavery’s horrors.

The ceremony included a reading from one of the few surviving fragments of Elina’s asylum letters, a passage that revealed her final understanding of what she had done. I told myself, I love Jordan, but love does not examine and measure in use. Love does not treat a human soul as a curiosity or a possession. I was as monstrous as Richard, perhaps more so because I disguised my monstrosity as affection.

If Jordan lives, I hope Jordan has found people who see a person rather than a phenomenon, who offered genuine love rather than obsession disguised as care. The fragment suggested that I lener in her asylum years had achieved some understanding of how her actions had harmed Jordan. Whether this understanding brought her peace or only deepened her torment remains unknown.

Today, Jordan’s story is taught in courses examining medical ethics, disability history, interex studies, and the complexities of sexual exploitation under slavery. It challenges comfortable narratives by presenting a victim who cannot be easily categorized, perpetrators whose motivations mixed scientific curiosity with sexual obsession, and a situation where both husband and wife participated in exploitation that ultimately destroyed everyone involved.

The question of what happened to Jordan after escape continues to haunt historians and descendants alike. Did Jordan successfully reach freedom? Did Jordan find community and acceptance? Did Jordan live long enough to see emancipation? Or did the trauma of those years at Belmont Plantation prove unservivable even after physical escape? The most hopeful interpretation preserved in oral tradition among descendants of enslaved people claims Jordan lived to old age in a remote Canadian community found peace working as a healer and died surrounded by

people who love Jordan for who Jordan was rather than what Jordan’s body represented to obsessed owners. Whether this ending is historical fact or wishful mythology may never be known, but perhaps that ambiguity is appropriate. Jordan deserves to be remembered not as a medical curiosity or a cautionary tale, but as a full human being whose story reminds us that slavery’s violence extended into the most intimate spaces.

That difference of any kind made enslaved people vulnerable to exploitation, and that obsession with controlling and categorizing bodies represents a violation of human dignity that continues to resonate in modern medical and social practices. Jordan’s silence in the historical record, the absence of a confirmed ending, stands as testimony to how completely slavery could erase people who already existed on the margins of accepted categories.

But the fragments that remain, the oral histories, the asylum letters, the medical notations, together create a portrait of someone who survived the unservivable and whose escape, whether to freedom or to death, represented a final assertion of agency that neither Richard nor Elaner could ultimately Control.