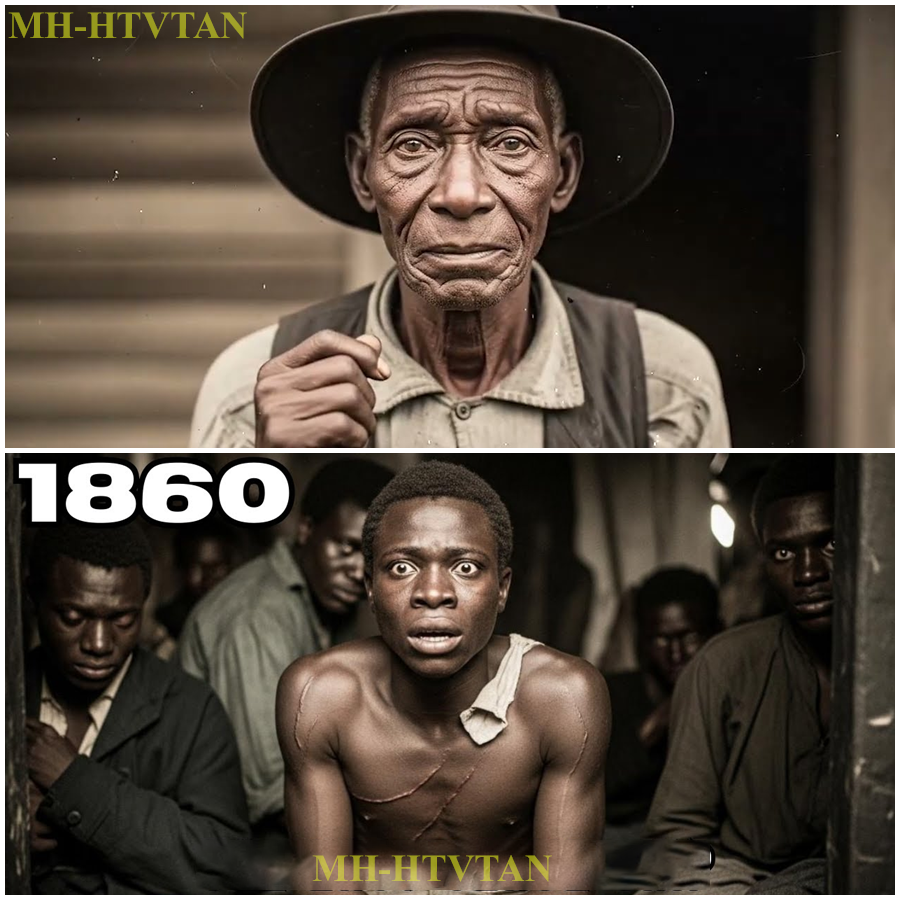

A child’s toy, a forked stick and a leather strip. but in the hands of someone with 5 years to practice.

Someone with nothing left to lose. Someone who understood that a stone traveling at 200 ft per second can crack a human skull like an egg. That simple weapon became the most feared thing in the Georgia mountains. This is the story of Isaiah Rivers. Age 15 when his campaign began. aged 20 when it ended. 29 slave catchers dead. And he was never caught, never even identified.

They called him the ghost, the phantom, the stone devil. But his real name was Isaiah. And this is how a boy with a slingshot brought terror to the men who terrorized his people. 29 men. That’s how many slave catchers died in the North Georgia mountains between November 1851 and May 1856. 29 men who made their living hunting human beings.

29 men who owned blood hounds and rifles and whips and chains. 29 men who rode through forests looking for runaways. who collected bounties measured in dollars per pound of human flesh returned. 29 men killed by stones. Smooth riverstones the size of a child’s fist launched from a slingshot made of hickory wood and deer leather traveling so fast the human eye couldn’t track them.

hitting skulls, temples, throats, eyes with such precision that doctors examining the bodies couldn’t understand how someone could achieve such accuracy. 29 men who went into the Georgia mountains hunting escaped slaves and never came back. And the person who killed them was a boy 15 years old when he started. self-taught, patient, invisible, waiting in trees and behind rocks and under bridges, waiting for hours, sometimes days, for the perfect shot.

One stone, one kill, then disappearing into the forest like smoke. For 5 years, slave catchers in North Georgia lived in fear. They traveled in larger groups. They wore extra clothing for padding. Some wore crude metal helmets. It didn’t matter. The stones found them anyway. Through fog, through darkness, through rain, the ghost never missed.

And he was never seen until now. Until we tell you who he really was and how he learned to kill with such terrible perfection. Isaiah Rivers was born enslaved in 1836 on a tobacco plantation in Cherokee County, North Georgia. His mother, Miriam, died giving birth to him.

His father, Jacob, raised him alone while working as a fieldand on the Morrison plantation, 500 acres of red clay hills and tobacco fields owned by a man named William Morrison, who believed that enslaved people were livestock that could talk.

Isaiah grew up thin and small for his age. At 8 years old, he looked six. At 12, he looked nine. Master Morrison called him the runt and said he’d never be worth much for field work. So Isaiah was assigned to lighter tasks, carrying water to field hands, collecting firewood, helping the plantation carpenter, running errands between the big house and the quarters.

It was during these childhood years of wandering the plantation that Isaiah discovered his gift. He could see details that others missed. A bird hidden in leaves 200 feet away, a snake coiled in grass, the exact moment a squirrel would move from one branch to another. His father, Jacob, noticed this and taught him to make a slingshot, not the crude forked stick that children played with, but a real hunting weapon.

Jacob had learned the craft from his own father, who had learned it in Africa before the Middle Passage. The weapon was simple. A Y-shaped piece of hickory wood hardened in fire. Two leather strips attached to the forks. A small leather pouch to hold the stone. The power came from the rubber-like elasticity of rawhide properly cured and the leverage of the wooden frame.

A stone launched from a well-made slingshot could travel over 200 ft per second. Fast enough to kill a rabbit at 50 paces. Fast enough to crack bone. Isaiah was 9 years old when his father first taught him to shoot. They would practice in secret in the forest on Sundays. The one day enslaved people had a few hours to themselves.

Jacob would set up targets, tree stumps, pieces of bark. Later, smaller targets, acorns on branches, knot holes in trees at increasing distances. Isaiah practiced for hours, thousands of shots over 3 years. By age 12 in 1848, Isaiah could hit a playing card at 50 ft. By 13, he could hit a coin at that distance.

By 14, he could hit a specific knot on a tree trunk at 70 ft. His father watched this skill develop with mixed feelings. Pride that his son had mastered something, fear about what that skill might be used for. This is for hunting food, Jacob told him again and again. Never for people. Never.

You use this on a white man, they’ll kill everyone on this plantation. You understand? Isaiah understood. He was 14 years old. He had never thought about using his slingshot on people. Not yet. That thought would come one year later on a September morning in 1850 when everything changed. September 15th, 1850. Isaiah was 14 years old. His father Jacob was 39.

They were working in the tobacco fields when the overseer, a man named Marcus Patterson, started whipping a woman named Sarah for working too slowly. Sarah was pregnant, 7 months along. She collapsed after the fifth lash. Patterson kept whipping. Jacob Rivers stepped forward and told Patterson to stop.

He didn’t shout, didn’t threaten, simply said, “Sir, she’s with child. Please.” Patterson turned and struck Jacob across the face with the whip handle. Jacob staggered but remained standing. field telling me what to do,” Patterson said. He pulled his pistol and shot Jacob Rivers in the chest once, point blank. Jacob fell into the red Georgia clay and died while his 14-year-old son watched from 30 ft away.

Isaiah stood frozen, his hands gripping the water bucket he’d been carrying. He watched his father’s blood soak into the dirt, watched Patterson holster his pistol casually. watched the other enslaved people return to work because there was nothing else they could do because helping meant dying too. Patterson looked around at the silent field hands.

“Any other want to tell me how to do my job?” he said. No one answered. Patterson walked away. Isaiah stood there for maybe 10 seconds longer. Then he dropped the bucket. The water spilled across the ground, mixing with his father’s blood. Isaiah ran, not to his father’s body, into the forest. He ran until his lungs burned and his legs gave out.

He collapsed behind a fallen oak tree two mi from the plantation and stayed there as the sun crossed the sky and the shadows lengthened. He stayed there as night fell and the temperature dropped. He stayed there thinking about his father’s face as the bullet hit him. The surprise in Jacob’s eyes. The way he’d fallen, reaching out as if trying to catch himself.

The casual tone in Patterson’s voice. Isaiah stayed behind that log until dawn. And when the sun rose on September 16th, 1850, he was a different person. The boy who had learned to shoot for hunting was gone. In his place was someone who understood a simple truth. If the system would kill his father for speaking, then the system needed to die.

And since he couldn’t kill the system, he would kill the people who enforced it. The slave catchers, the bounty hunters, the men with blood hounds who hunted runaways, the men who made slavery possible by making escape nearly impossible. Those men could be killed. And Isaiah Rivers had spent 5 years learning exactly how to kill them.

But Isaiah didn’t rush. That’s the important part. That’s what made him different from others who attempted revenge and died quickly. Isaiah understood that one boy with a slingshot couldn’t fight the entire system openly. He had to be invisible, patient, strategic. So he waited. He worked in the fields. He obeyed orders. He kept his head down.

He grieved his father publicly like enslaved people were allowed to grieve which meant quietly and briefly before returning to work. And secretly at night in the forest he planned. Isaiah studied the slave catchers who operated in Cherokee County. There were eight regular hunters who worked the territory.

white men aged 25 to 50 who owned blood hounds and rifles and made their living catching runaways and returning them for bounties. $50 for a man, $30 for a woman, $20 for a child. Dead or alive, though alive was worth more. These men were professionals. They knew the forests. They knew where runaways hid. They knew how to track and trap and capture. They were dangerous.

But they had patterns. Isaiah learned those patterns over months of careful observation. He would claim to be checking trap lines or gathering firewood and would spend hours watching the slave catchers move through the forest. He memorized their roots. Robert Morrison always checked the cave systems near Blood Mountain on Wednesdays.

Thomas Whitfield patrolled the Edeto River creek beds on Mondays and Thursdays. Marcus Johnson worked the Chattahuchi ridge lines on weekend mornings. Each man had his territory, his schedule, his habits. Isaiah filled a mental map with their movements, their preferences, their vulnerabilities. They were predictable, and predictable men could be ambushed.

Isaiah also studied his weapon with the intensity of an engineer. He rebuilt his slingshot multiple times using the hardest hickory he could find from the forest floor, testing different fork angles to maximize power and accuracy. He experimented with different leather types for the bands, trying deer skin, cowhide, and rawhide.

Finally settling on rawhide cured in a specific way that gave maximum elasticity without breaking. His father had taught him the basics, but Isaiah elevated the weapon to a science. He learned that pulling the bands back exactly 17 in gave optimal velocity without overstressing the leather. He learned that releasing with his thumb and forefinger rather than full hand gave more consistent accuracy.

He learned that breathing affected aim, so he always exhaled completely and shot between heartbeats when his body was stillest. He collected stones with obsessive care. Smooth river stones from High Tower Creek, each one weighing between 1.8 and 2.2 oz. Each one tested for balance by spinning it on his palm.

Stones that wobbled were discarded. Only perfect spheres were kept. He sorted them by weight and shape into categories. Light stones for long distance, heavy stones for close range and maximum impact. He hid them in various locations throughout the forest, burying them in marked spots near likely ambush sites, so he always had ammunition nearby.

He even tested different stone types. Riverstones were good. Certain types of granite were better because they were denser and held together better on impact. He kept his best stones, the ones he called his killing stones, in a leather pouch he wore around his neck under his shirt. 12 perfect stones, smooth, dense, balanced, each one capable of cracking a human skull.

He practiced with an intensity that bordered on obsession. Every night after work claiming he was setting rabbit snares, Isaiah would go into the forest and shoot. Not random shooting, systematic training. He created a practice course through the forest near the plantation. Targets at different distances, 20 yards, 30 yards, 40, 50, 60, 70.

He marked each distance with a stone can so he could train his eye to judge range instantly without thinking. He set up targets that simulated shooting at humans. Pumpkins placed at head height on posts. Stuffed sacks hanging from tree branches that swayed in wind. Pieces of bark with circles drawn on them in charcoal getting smaller as his accuracy improved.

He practiced until his arms achd, until his hands cramped, until the muscles in his back and shoulders burned, until he could load and shoot in complete darkness by feel alone, finding the pouch by touch, feeling the stone settle into place, drawing back to the exact 17in position without measuring, he practiced the most critical skill of all, shooting from awkward positions, hanging from tree branches, with one hand, lying on his back, looking up, kneeling behind rocks with limited movement, shooting uphill and downhill,

which required different aim compensation because gravity affected the stone’s trajectory. He practiced in rain, in fog, in wind. He learned how different conditions affected the stone’s flight. Rain added weight and slowed velocity. Wind pushed stones sideways, requiring aim adjustment. Cold made the leather bands stiffer and less powerful, requiring harder poles.

He compensated for everything, built tables in his mind of conditions and corrections. He practiced shooting and moving, the combat skill his father had never taught him because his father had never imagined Isaiah would need it. Take the shot. Sprint 20 ft. Reload. Shoot again from new angle. Sprint again.

Building muscle memory for situations where one shot might not be enough or where the targets companions would search for him. He timed himself obsessively. He could load and shoot three times in 6 seconds. He could shoot, sprint 50 ft through dense forest, and be completely hidden in brush in under 10 seconds. He practiced until everything was automatic.

Until he could wake from sleep and shoot accurately within seconds, until the slingshot was an extension of his body, an extra limb that responded to thought without conscious control. Isaiah spent 13 months preparing from September 1850 to November 1851. 400 days, over a thousand hours of practice, tens of thousands of shots fired at targets.

Other enslaved people noticed him disappearing into the forest at night, but assumed he was trapping game for extra food. Master Morrison’s overseer questioned him once about his nighttime activities. Isaiah showed him six rabbits he had killed with the slingshot, and said he was providing meat for the quarters. The overseer, satisfied that Isaiah was just hunting food, left him alone.

No one suspected he was building himself into a weapon. No one realized that the thin 15-year-old boy was practicing to kill men from 70 yard away in any weather, from any position without missing. By November 1851, Isaiah was 15 years old, 5’4 in tall, 110 lb. He could hit a man-sized target at 70 yards nine times out of 10.

He could shoot three times in 6 seconds with consistent accuracy. He could kill silently from distance without being seen. He knew every slave catcher’s pattern. He had ammunition hidden throughout the forest. He had escape routes planned for every possible ambush location. And he was ready. Ready to honor his father, Jacob Rivers. Ready to make slave catchers afraid.

Ready to start killing. November 3rd, 1851. Isaiah’s first kill. The target was a slave catcher named Robert Morrison, age 42, who worked alone with two blood hounds. Morrison checked a cave system near Blood Mountain every Wednesday morning like clockwork. Isaiah had watched him do this for three months, timing his arrival, noting his route, identifying the best ambush position.

The same pattern every week, the same path through the same trees. Predictable. On November 3rd, Isaiah left the plantation at dawn, claiming to check rabbit snares. He reached the cave system by 7 in the morning and positioned himself in an oak tree 60 ft from the path Morrison would take. The tree was old with thick branches that wouldn’t crack under his weight.

The leaves were still full despite autumn providing cover. Isaiah settled into position, slingshot ready, a killing stone already loaded. He waited. Waiting was the hardest part. Not the shooting, the waiting. 3 hours sitting absolutely still in the tree while his muscles stiffened and his back achd. fighting the urge to shift position, to stretch, to move.

Three hours watching the forest, listening for footsteps. Three hours thinking about his father’s face, about Patterson’s casual violence, about the system that made such violence normal. At 10:15 in the morning, Morrison appeared with his dogs. He was walking slowly, letting the blood hounds sniff the ground, checking for signs of runaways using the caves.

The dogs were well-trained, silent, focused on their work. Morrison carried a rifle slung over his shoulder and a coiled rope on his belt, the tools of his trade. Isaiah waited until Morrison was 55 ft away. Broadside angle. Morrison’s left temple exposed. No wind. Perfect visibility. Morning sun behind Isaiah so Morrison wouldn’t see a silhouette if he happened to look up.

Isaiah pulled the slingshot back smoothly, feeling the leather stretch, the familiar resistance against his fingers. The pouch pressed against his cheek. His left arm pointed directly at Morrison’s head like a rifle sight. He exhaled completely found the space between heartbeats. Released. The stone flew faster than Morrison could react.

Faster than the human eye could track. A gray blur covering 55 ft in a fraction of a second. It hit Morrison in the left temple with a sound like a branch breaking. A sharp crack that echoed once, then faded. Morrison dropped instantly. No cry, no stumble, just vertical to horizontal in an instant. His rifle clattered to the ground, his dog startled and bolted into the forest, confused by their master’s sudden fall.

Morrison lay on the ground, convulsing for maybe 15 seconds, his legs kicking, his hands clawing at nothing. Then he went still. Isaiah watched from the tree, watched Morrison die, felt his own hands shaking, not from fear, not from guilt, from adrenaline flooding his system. From the realization that he had just killed a man, that it had been easy, that Morrison had never seen it coming.

Isaiah waited five more minutes to make sure Morrison was truly dead and the dogs weren’t returning. Then he climbed down from the tree, approached carefully, checked that Morrison had no pulse. The stone was embedded in Morrison’s skull, driven into the bone by the force of impact. Isaiah didn’t retrieve it.

Touching the body was too risky. He turned and disappeared into the forest, moving quickly but carefully, leaving no trail. The entire event from shot to departure took less than 3 minutes. Morrison’s body was found 3 days later by another slave catcher who had gone looking when Morrison didn’t return. Cause of death was obvious.

Massive skull fracture to the left temple. But the mechanism was mysterious. No bullet wound, no blade marks, just a circular depression in the skull about an inch across with a smooth stone driven into the bone. The local sheriff examined the body and concluded Morrison had fallen and hit his head on a rock. Case closed.

Accident. Isaiah had committed perfect murder. The second kill came two weeks later, November 18th, 1851. Thomas Whitfield, age 38, another solo slave catcher who worked with dogs. Isaiah ambushed him on a trail near the Edeto River. Same method, stoned to the head at 60 ft. Whitfield dropped without a sound. His dogs ran.

Isaiah disappeared. Body found 4 days later. Again, ruled accidental death by falling. The third kill came in December 1851. Marcus Johnson, age 45. Johnson was more careful than the previous two, constantly scanning the forest, never staying still for long. But careful wasn’t enough. Isaiah waited in position for 6 hours before Johnson finally paused in the right location.

One stone, temple shot, dead before he hit the ground. But this time, Johnson’s partner, a man named Samuel Brooks, found the body within hours and noticed something wrong. There were no rocks near Johnson’s body that could have caused the skull fracture he suffered. The injury was on top of his head, which made falling implausible unless he had fallen from a significant height.

But there were no cliffs or ledges nearby. Brooks reported this to the sheriff, who conducted a more careful examination and realized something disturbing. Johnson, Whitfield, and Morrison had all died from nearly identical injuries. circular skull fractures, all on the head or temple. All roughly the same size.

Three slave catchers dead in six weeks. All from mysterious head injuries. The sheriff concluded the deaths were murders, not accidents. But how? No bullets, no blades, no witnesses, no evidence, just three dead men with crushed skulls. The sheriff warned the remaining slave catchers in Cherokee County to travel in groups and stay alert.

Someone or something was killing them in the forest. They began calling it the mountain curse. Some thought it was a bear attack. Others claimed a ghost or forest spirit was taking revenge. A few suspected it was an escaped slave hiding in the mountains. But that theory seemed implausible. No escaped slave could survive months in the Georgia winter.

None of them understood what they were dealing with. None of them realized they were being hunted by a 15-year-old boy with a slingshot who had already killed three times and was just getting started. January through April 1852, four more kills. Isaiah was methodical. He never struck twice in the same location.

He varied the time between kills, sometimes waiting 3 weeks, sometimes only one. He chose targets carefully, always slave catchers who worked alone or in pairs, always ambushing them in locations where their bodies wouldn’t be found immediately. Each kill was identical in method, stone to the head, usually temple or top of skull. Instant death, silent, invisible.

Isaiah’s skill had progressed to the point where he could predict exactly where the stone would hit based on distance, angle, and target movement. He aimed for the temple because the bone was thinnest there. A stone hitting the temple at 200 ft pers didn’t just break the skull. It drove bone fragments into the brain, causing immediate catastrophic damage.

Death was instantaneous. No suffering. Isaiah wasn’t sadistic. He was efficient. But each kill weighed on him differently than he expected. He had thought revenge would feel satisfying. It didn’t. Each time he watched a man drop dead from his stone, Isaiah felt nothing. No joy, no satisfaction, no sense of completion, just a mechanical acknowledgement.

Target down. Move to next. He was becoming exactly what the system had made him, which was a killer who felt nothing because feeling anything was dangerous. The only emotion he allowed himself was the memory of his father’s face when the bullet hit him. That memory fueled everything.

That memory kept him going through cold nights waiting in trees. That memory steadied his hand when he pulled back the slingshot. That memory was all he had left of Jacob Rivers, and Isaiah protected it like a sacred flame that could never be allowed to go out. By May 1852, seven slave catchers were dead in Cherokee County. The local sheriff, overwhelmed and unable to solve the murders, requested help from the state.

Georgia sent investigators, experienced men from Atlanta who had dealt with slave rebellions and fugitive cases. They examined the bodies, interviewed witnesses, searched the forests systematically. They found nothing. No tracks because Isaiah always shot from rocky areas where footprints didn’t show or from trees that left no ground trail.

No abandoned weapons because Isaiah carried his slingshot with him always, and the stones themselves were indistinguishable from thousands of other riverstones scattered throughout the forest. No witnesses because Isaiah only shot when he was certain he was alone with his target when no other hunters or travelers were within sight or hearing.

The investigators concluded they were dealing with someone highly skilled, probably an escaped slave with military or hunting experience, someone who was systematically eliminating slave catchers for revenge. They were halfright. It was systematic elimination. It was revenge, but it wasn’t an escaped slave. It was a current slave who reported to work every morning and never missed a day.

Who appeared to be a model of obedience and submission who no one suspected because he was 15 years old and weighed 110 lb and seemed incapable of violence. Isaiah’s camouflage was perfect. He was invisible, not because he hid in forests, but because he hid in plain sight as someone beneath notice. A runt, a water carrier, a boy. Bounties were posted.

$200 for information leading to the killer, $500 for capture. Slave catchers began traveling in groups of four or five, heavily armed, constantly watching the trees. They scanned tree lines. They varied their roots. They moved faster through the forests, spending less time in any one location. Some refused to work Cherokee County at all, taking contracts in safer counties where mysterious deaths weren’t occurring.

Slave catcher conventions were held in Atlanta, where the professionals gathered to discuss the problem. Was it one person or several? Was it an organized conspiracy or a lone operator? How could someone kill seven men without leaving a single clue? The professionals had no answers. They only had fear. And that fear spread through the entire network of slave catchers across Georgia.

If seven could die in Cherokee County, how many would die elsewhere? The profession began to contract. Men quit. Prices tripled for those still willing to work. The system that had relied on professional slave catchers to make slavery viable was beginning to crack because one 15-year-old boy with a slingshot had decided to fight back.

But Isaiah adapted to their new tactics. Larger groups meant more targets. It just meant he had to be more careful, more patient, more precise. June 1852, Isaiah’s eighth kill. This time the target was a group of four slave catchers traveling together for safety. They were following High Tower Creek Bed at midday when Isaiah struck from a ridge 70 yard away.

Difficult shot, longer distance than usual. Moving target, but Isaiah had been practicing this exact scenario. He killed the lead man with the first stone. Temple shot. The man dropped without making a sound, falling forward into the creek. The other three scattered for cover immediately, professional instincts taking over.

They shouted to each other, looking around wildly, trying to identify the threat. They never saw Isaiah, never looked up at the ridge. They fired their rifles randomly into the forest, shooting at shadows and imagined enemies. Isaiah waited, invisible in thick brush 70 yard away. He was in no hurry. He could wait all day if necessary. 15 minutes passed.

The three survivors regrouped around their dead companion, trying to understand what had happened. One of them, a man named David Patterson, examined the body carefully and found the stone. He pulled it from the skull where it had embedded. A smooth riverstone, perfectly round, covered in blood and brain matter. “Slingshot,” he said, his voice showing disbelief.

Someone killed him with a goddamn slingshot. The three men looked at each other trying to process this information. A slingshot? That was a child’s toy. Who could kill a grown man with a slingshot from this distance? They decided to carry their companion’s body out of the forest immediately. No more hunting today.

They were loading the corpse onto a horse when Isaiah fired again. He had relocated during their confusion, moving 30 yards to a new position with a better angle. The second stone hit David Patterson in the back of the head. He fell forward across the horse’s back. The remaining two men panicked completely.

They abandoned both bodies. They ran, crashed through the forest without looking back, certain they would be next. They ran until they reached the main road where they found other travelers and finally felt safe. They reported to the sheriff that the forest ghost was real and was killing with stones. No one believed them at first.

The local newspaper ran a mocking article about slave catchers scared by pebbles, suggesting they had imagined the deaths. But when a search party went to recover the bodies the next day, they found both men dead with identical injuries. Skull fractures from smooth stones. The mocking stopped. The fear became real. The terror spread.

July through December 1852. Five more kills. Isaiah was now 16 years old. 2 years into his campaign. 13 slave catchers dead. Cherokee County couldn’t find anyone willing to hunt runaways for any price. The profession had become too dangerous. Slave owners in the county began offering massive bounties up to $1,000 for the capture of whoever was killing the slave catchers.

The governor of Georgia, concerned about the breakdown of slave control, sent a military detachment of 20 soldiers to patrol the forests and establish a visible presence. Isaiah simply waited. He didn’t kill for 3 months while soldiers were present. He worked in the tobacco fields. He obeyed orders.

He appeared to be exactly what he was supposed to be, a young enslaved man who spent his days working and his nights sleeping. The soldiers patrolled the forests, found nothing suspicious, and withdrew in October, declaring the area secure. Two days after the soldiers left, Isaiah killed two more slave catchers. Same method, stones to the head, silent, invisible, gone before bodies were discovered.

The pattern continued through 1853 and 1854. Isaiah killed slowly now, one every 2 or 3 months, 20 total. By the end of 1854, he was 18 years old. He had spent 3 years making Cherokee County essentially impossible for slave catchers to operate in. Runaways began using Cherokee County as a safe corridor. Word spread through the Underground Railroad network that North Georgia, specifically Cherokee County, was where slave catchers didn’t go.

The ghost, as they now called him, had created a killing zone where the hunters became the hunted, where enslaved people could move through relatively safely because the men paid to catch them were too afraid to enter. But Isaiah’s campaign wasn’t without close calls. In March 1854, a slave catcher named William Brooks came within 20 ft of Isaiah’s hiding spot in a tree.

Brooks stood directly under the oak where Isaiah was concealed, letting his dogs rest, completely unaware that his killer was 10 ft above his head. Isaiah’s slingshot was loaded. One stone ready. He could have killed Brooks easily. Point blank range. Impossible to miss. But Isaiah didn’t shoot. Too close. Too risky.

If the shot wasn’t instantly fatal, if Brooks had time to look up and see him before dying, Brooks might shout, might identify him. And if Brooks identified Isaiah as an enslaved person, investigators would question every enslaved person in the county. They would eventually trace him to the Morrison plantation. Everyone there would be tortured until someone revealed Isaiah’s nighttime activities.

So Isaiah waited in the tree, absolutely motionless, barely breathing, while Brooks sat directly below him for almost an hour. Isaiah’s muscles cramped. His back achd. He needed to shift position desperately, but couldn’t move even slightly. Brooks smoked a pipe, talked to his dogs, ate some food, stretched out on the ground, and actually dozed for 20 minutes.

Isaiah remained frozen in place above him, fighting the screaming pain in his legs, the burning in his shoulders, the desperate need to move. Finally, Brooks stood, stretched, called his dogs, and moved on down the trail. Isaiah waited another two full hours to make absolutely certain Brooks was gone before climbing down from the tree.

He collapsed when he reached the ground, his legs numb, his hands shaking. That was the closest he had ever come to being discovered. That night, lying in his quarters, Isaiah realized how easily the entire campaign could end. One mistake, one moment of impatience, one bad decision. After that incident, Isaiah became even more careful.

He increased the minimum distance for shots to 70 yard, no exceptions. He never took a shot unless he had at least two escape routes planned and verified. He practiced his disappearing act until it was instinctive. Shoot and move and vanish all within seconds. He studied every slave catcher’s patterns even more carefully.

He memorized their faces, their voices, their habits. He knew which ones traveled armed with multiple weapons and which carried only a rifle. He knew which ones were skilled trackers who might notice broken twigs or disturbed earth and which were amateurs just trying to make easy money. He prioritized the most dangerous ones, the real hunters, the ones who actually knew what they were doing because those were the ones most likely to eventually track him down if he left them alive.

By 1855, Isaiah had killed 22 slave catchers. He was 19 years old. He had been conducting this campaign for 4 years without missing work, without arousing suspicion from Master Morrison, without ever being seen by any of his targets. The slave catcher profession in North Georgia had essentially collapsed. Men who had made their living hunting runaways switched to other work.

The few who remained charged triple rates and refused to work alone under any circumstances. Some wore crude armor, leather padding under their clothes, metal plates over their chests, thinking this would protect them. None of it mattered. Isaiah’s stones found exposed heads and throats regardless of body protection.

The kills continued. One in March 1855, one in May, two in August. Each one identical to the first. Stone to the skull, instant death. No witnesses, no evidence. By January 1856, Isaiah had killed 25 slave catchers. He was 20 years old, 5 years into his campaign. And then something changed. Master William Morrison died of a heart attack in February 1856.

His son, Thomas Morrison, inherited the plantation. Thomas was 28 years old, educated at a college in Virginia, and much more suspicious than his father. Thomas noticed that Isaiah, now a young man of 20, frequently disappeared into the forest at night. Thomas ordered the overseer to follow Isaiah and report back.

The overseer, a man named George Wilson, tracked Isaiah for three nights and discovered he was going deep into the forest, staying for hours, then returning before dawn. Wilson couldn’t get close enough to see what Isaiah was doing, but the pattern was suspicious. Wilson reported this to Thomas Morrison, who immediately suspected Isaiah was either meeting with runaways, helping fugitives escape, or possibly involved in the slave catcher killings that had plagued the county for 5 years.

Thomas Morrison decided to set a trap. March 1856, Thomas Morrison hired four slave catchers from South Carolina, men who didn’t know about the killings in Cherokee County and wouldn’t be afraid to work there. He told them there might be a large group of runaways hiding in the forests near his plantation and he wanted them found and returned.

He didn’t tell them they were bait. He didn’t tell them that he suspected one of his enslaved people was the ghost. The four slave catchers arrived on March 10th. That night, Thomas Morrison had his overseer, George Wilson, follow Isaiah when he left for the forest. Wilson followed at a distance, staying hidden, moving carefully.

Isaiah went to his usual practice area, a clearing near High Tower Creek about 2 mi from the plantation. He began shooting at targets he had set up, practicing as he had done thousands of times before. Wilson watched from hiding behind dense brush. He saw Isaiah load the slingshot, saw him pull back with perfect form, saw stones strike tree trunks 70 yard away with tremendous force embedding in the wood.

Wilson watched for 15 minutes, counting six shots, each one hitting exactly where Isaiah aimed. Wilson understood immediately what he was witnessing. This young enslaved man was the ghost. The one who had killed 25 slave catchers. The one who had terrorized an entire profession. Wilson silently withdrew and returned to report to Thomas Morrison.

Thomas Morrison now had proof. He had witnessed testimony from his overseer that Isaiah Rivers was the killer. Thomas could have Isaiah arrested, tortured publicly, executed as an example to other enslaved people considering resistance. The Thomas Morrison was a businessman. He saw an opportunity. The next morning, March 11th, Thomas Morrison called Isaiah to the big house.

Isaiah had no idea he had been followed. He expected punishment for disappearing at night, maybe a whipping for leaving the plantation without permission. Instead, Thomas Morrison sat Isaiah down in his study and said, “I know what you’ve been doing. George Wilson saw you last night.

You’ve been killing slave catchers for 5 years. You’re the one they call the ghost.” Isaiah’s blood went cold. He calculated his options rapidly. Deny everything, run, attack Morrison, and try to escape. But Morrison continued, “I should have you hanged. should make an example of you. But I have a better idea. I have four slave catchers here from South Carolina.

They’re looking for runaways in my forests. I want you to kill them. All four. Tonight. If you do, I’ll give you your freedom papers and $200. If you refuse, I’ll have you arrested and you’ll hang publicly. Choose now. Isaiah stared at Thomas Morrison, understanding the trap. Morrison wanted the four slave catchers dead because they were witnesses to something.

Maybe plantation conditions Morrison didn’t want reported. Maybe they had seen something they shouldn’t have. Morrison was using Isaiah as a tool, a weapon. But Morrison was also offering freedom. Real freedom. Legal papers. money. Everything Isaiah’s father had dreamed of. All Isaiah had to do was kill four more men. Four men who hunted enslaved people for profit.

Four men who represented everything Isaiah hated. Four men whose deaths would bring his total to 29. I’ll do it, Isaiah said quietly. But I want the papers first. and $300. Thomas Morrison smiled. It wasn’t a friendly smile. $250 and you get the papers after the job is done. If you run, I’ll report everything and every sheriff in Georgia will hunt you.

Do we have an agreement? Isaiah thought about his options. He had none. Agreement, he said. That night, March 11th, 1856, Isaiah Rivers killed four men in 90 minutes. The four South Carolina slave catchers had set up camp in the forest 2 mi east of the Morrison plantation. They had a campfire. They had posted one guard on rotation. They thought they were safe because no one except Thomas Morrison knew they were there.

They didn’t know Thomas Morrison had hired them to die. Isaiah approached the camp at midnight. He positioned himself on a ridge 80 yard away, higher elevation, perfect angle. He could see all four men in the fire light. Three were sleeping near the fire. One was awake, sitting up, smoking a pipe. Isaiah killed the smoking man first, single stone to the head.

The man slumped forward without a sound. The fire light made targeting easy. Isaiah killed the three sleeping men in rapid succession. Load, aim, shoot. Load, aim, shoot. Load, aim, shoot. Three stones, three kills, six seconds total. All four men dead before any of them fully woke. Isaiah climbed down from his position, approached the camp carefully, verified all four were dead.

Then he returned to the Morrison plantation and reported to Thomas Morrison. “It’s done,” Isaiah said. Thomas Morrison sent George Wilson to verify. Wilson found all four bodies and reported back. Thomas Morrison kept his word. He gave Isaiah freedom papers, legal manuum mission documents stating that Isaiah Rivers was freed by his master in recognition of faithful service and $250 in cash. You’re free.

Thomas Morrison said, “Take your papers and leave Georgia tonight. If you stay, someone will eventually connect you to those 29 dead slave catchers and they’ll hang you regardless of what those papers say. Go north. Go to Ohio or Pennsylvania. Disappear. And if you ever tell anyone I hired you to kill those four men, I’ll hunt you down myself.

Isaiah took the papers and the money. He packed his few belongings into a small bag. And that night, March 12th, 1856, he left Georgia forever. He was 20 years old. He had killed 29 slave catchers in 5 years. He had never been identified by authorities, never been caught, never even suspected by anyone except Thomas Morrison and George Wilson, who both had reasons to keep his secret forever.

Isaiah Rivers disappeared into the Underground Railroad network and reached Ohio by April 1856. He settled in Cincinnati and worked as a carpenter using skills he had learned on the Morrison plantation. He lived quietly. He never told anyone about his 5 years in the Georgia mountains. He married in 1860, had four children, worked for 40 years building houses and furniture.

He was never arrested, never questioned, never connected to the 29 dead slave catchers whose bodies had been found in Cherokee County between 1851 and 1856. The official investigations concluded the deaths were caused by an escaped slave who had likely been recaptured or killed himself. The cases were closed.

The ghost was forgotten. But Isaiah Rivers never forgot. In 1898, when he was 62 years old, dying of tuberculosis in a Cincinnati hospital, Isaiah told his story to a young black newspaper reporter named Frederick Davis. Isaiah knew he was dying. He wanted someone to know the truth.

He wanted his father, Jacob’s death, to be remembered. He wanted those 29 slave catchers to be remembered, too. not as victims, but as exactly what they were, professional hunters of human beings who died doing evil work. The interview lasted 3 days. Frederick Davis visited Isaiah’s hospital room each afternoon and listened as the dying man described his 5 years in the Georgia mountains.

Isaiah’s voice was weak, but his memory was perfect. He remembered every kill, every face, every stone that found its mark. He described Robert Morrison falling after the first shot, the way his legs had kicked as he died. He described the panic in the eyes of the four slave catchers when their companions dropped dead with no warning. He described the cold calculation required to kill four men in one night for his freedom.

He described 13 months of practice before taking his first life. He described the weight of the slingshot in his hand and the feeling of absolute certainty when he released a stone knowing it would kill. Frederick Davis took notes covering 40 pages of detailed testimony. He asked Isaiah if he felt guilty about the 29 deaths.

Isaiah’s answer was clear and immediate. I feel nothing for those 29 men. They chose to hunt human beings for money. They chose to separate families and drag people back to slavery. They chose evil work. I just chose to stop them. The only guilt I carry is that I couldn’t save my father. That I was too young and too weak to intervene when Patterson shot him.

Everything I did after that was to honor Jacob Rivers. To prove that his death mattered, to prove that enslaved people could fight back, to prove that we weren’t helpless victims waiting for white saviors. Davis asked if Isaiah would do it again if given the choice. Isaiah smiled, a thin smile from his hospital bed and said, “Every stone, every kill, every night waiting in cold trees.

I’d do it all again because 29 dead slave catchers meant hundreds of runaways made it to freedom through Cherokee County.” That’s the mathematics that matters. 29 evil men dead, hundreds of families saved. I’ll face God with those numbers and let him judge. Frederick Davis published Isaiah’s confession in a black newspaper called The Cincinnati Defender in October 1898, shortly after Isaiah’s death.

The article was titled The Stone Ghost: How One Boy’s Slingshot Brought Terror to Georgia Slave Catchers. The article described Isaiah’s 5-year campaign in detail. The methods, the patience, the skill, the 29 kills. White newspapers in Georgia denounced the article as fiction, claiming no one could kill 29 men with a slingshot.

But the facts checked out. 29 slave catchers had indeed died in Cherokee County between 1851 and 1856. The deaths had indeed been mysterious with identical injuries. The cases had never been solved. Isaiah Rivers had been real. His campaign had been real. His 29 kills had been real. The stone ghost was not a myth or exaggeration.

He was a 15-year-old boy who watched his father murdered for asking an overseer to stop whipping a pregnant woman and decided to systematically eliminate the men who made slavery possible by hunting escapees. He was a patient hunter who spent 13 months preparing before taking his first shot.

He was a skilled marksman who killed from 70 yards with a child’s weapon. He was a ghost who operated for 5 years without being identified. And he was a human being who earned his freedom by doing what the system forced him to do, which was kill or die. The article created controversy that lasted months. Abolitionists celebrated Isaiah as a hero who fought the only way available to him.

Pro-slavery advocates claimed the story proved that enslaved people were dangerous and needed even stricter control. The debate missed the point entirely. Isaiah Rivers wasn’t a hero or a villain. He was a boy whose father was murdered and who found a way to fight back within the brutal constraints of his situation. He couldn’t lead a rebellion.

He couldn’t escape to freedom immediately. He couldn’t appeal to law or justice because law and justice didn’t apply to him. So he became a sniper. He became a hunter of hunters. He became someone who could deliver precise violence from distance without being caught. And he did it for 5 years with ruthless efficiency.

The legacy of Isaiah Rivers extends beyond numbers. Yes, 29 dead slave catchers is significant. Yes, 5 years of successful operations is remarkable. Yes, never being caught is extraordinary. But the deeper impact was psychological and systematic. Isaiah Rivers, working alone with nothing but a slingshot, made an entire profession afraid to operate in his territory.

He created a safe corridor through North Georgia that the Underground Railroad used for years. He personally prevented hundreds, maybe thousands of recaptures because slave catchers avoided Cherokee County entirely, unwilling to risk their lives for bounties. He proved that enslaved people weren’t helpless victims waiting for liberation.

That one person with skill and determination could fight back effectively. that the hunters could become the hunted, that resistance didn’t require guns or numbers or outside help. It required patience, planning, practice, and the willingness to do what was necessary. Isaiah Rivers demonstrated all of those qualities over 5 years and 29 kills.

He wasn’t a revolutionary leading a rebellion. He was a carpenter’s son with a slingshot who understood that sometimes justice arrives one stone at a time. 29 stones. 29 men who thought they were safe because they had dogs and rifles and the law on their side. 29 men who never saw the stone that killed them. 29 men who learned too late that a motivated 15-year-old boy with 5 years to practice and nothing left to lose is more dangerous than any weapon they could imagine.

Isaiah Rivers died in Cincinnati on October 7th, 1898. He was 62 years old. His grave marker reads simply Isaiah Rivers 1836 to 1898. Carpenter, husband, father. He lived free. His children didn’t learn about their father’s past until after his death when they read Frederick Davis’s newspaper article. They couldn’t reconcile it with the quiet man who had built furniture and houses for 40 years, who had never raised his voice, who had seemed gentle and kind.

But Isaiah’s oldest son, Jacob, named after his grandfather, understood after reading the article multiple times. He kept a copy and passed it down through the family. That article still exists today. It’s in an archive at the University of Cincinnati, part of a collection of 19th century black newspapers. You can read Isaiah’s confession yourself in his own words as recorded by Frederick Davis, describing how he learned to kill with a slingshot, how he planned each ambush, how he felt watching slave catchers die, how he

earned his freedom by becoming what the system forced him to become. Remember Isaiah Rivers. Remember that he was 15 years old when he started. Remember that his father Jacob was murdered for asking an overseer to stop whipping a pregnant woman. Remember that Isaiah spent 13 months preparing before taking his first life, practicing thousands of hours to achieve perfect accuracy.

Remember that he killed 29 men in 5 years and was never caught. Remember that his weapon was a forked stick and a leather strip and smooth stones from a creek. Remember that he created terror with something slave owners considered a child’s toy. Remember that he made an entire profession afraid to operate in his territory.

Remember that he earned his freedom by killing the four men Thomas Morrison wanted dead. Remember that he lived 42 more years as a free man, built houses, raised children, and died in his own bed surrounded by family. Remember that the system tried to break him and failed. Remember that one person with skill and determination and absolute commitment can make a difference.

Remember that resistance takes many forms. Remember that justice sometimes arrives one stone at a time. Remember Isaiah Rivers, the stone ghost of Georgia, born enslaved 1836, died free 1898. Age 15 when his campaign began. Age 20 when it ended. 29 slave catchers dead. And he was never caught.