On August 14th, 1827, in the rice plantation surrounding Charleston, South Carolina, a plantation owner named Josiah Crane was found dead in his library. His skull crushed so completely that physicians examining the body reported bone fragments embedded in the mahogany desk 6 ft away.

The coroner’s report, still preserved in Charleston County archives, described injuries consistent with compression by hands of extraordinary size and strength, exceeding normal human capacity.

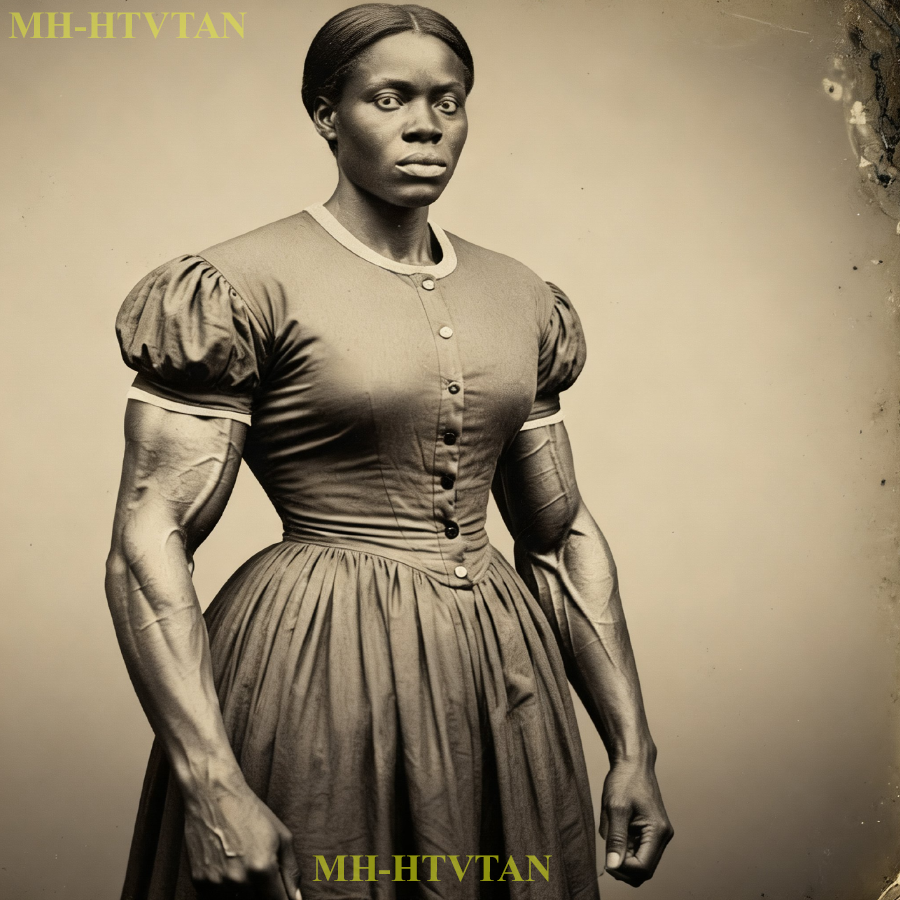

The only suspect was a woman who stood 6’8 in tall, weighed over 240 lb of solid muscle, and had vanished into the August night without a trace. For nearly two centuries, local historians have debated whether Sarah Drummond really existed or if she was merely a legend born from guilt and fear.

But the medical records, sale documents, and eyewitness testimonies suggest something far more disturbing. That she was absolutely real and that what happened in that library was the inevitable conclusion of a horror that had been building for years.

The story of Sarah Drummond does not start with violence. It starts with money. In the spring of 1823, the port of Charleston was experiencing one of its busiest trading seasons in decades. Ships arrived weekly from the Caribbean, from West Africa, from the tobacco regions of Virginia, all carrying human cargo to be sold at the markets on Charmer Street and Gadsden’s Wararf.

Charleston was not just a port city. It was the beating heart of the domestic slave trade in the American South, a place where fortunes were made through the buying and selling of human beings with the same casual efficiency as cotton bales or rice barrels. The rice plantations that surrounded Charleston were particularly brutal operations.

Unlike the cotton fields further inland, rice cultivation required workers to stand in water for hours at a time in swamps teeming with malaria carrying mosquitoes, venomous snakes, and alligators. The death rate among enslaved workers on rice plantations was staggering. Some historical estimates suggest that nearly 30% of enslaved people working in the rice fields died within their first year.

The work was so dangerous, so exhausting, so deadly that plantation owners constantly needed to purchase new workers to replace those who had perished. This created a perverse economy. Slave traders scoured the southern states looking for strong, healthy workers who could withstand the brutality of the rice swamps.

And occasionally they found something unusual, something that would fetch an extraordinary price. In March of 1823, a slave trader named Caleb Rutherford arrived in Charleston with a coff of 37 people he had purchased in Virginia and North Carolina. Among them was a young woman, perhaps 19 or 20 years old, who immediately drew attention for one unmistakable reason. She was enormous.

Contemporary accounts from the auction house records describe her as standing near 7 ft in height with a frame of unusual breadth and musculature. Witnesses at the auction reported that she had to duck to enter doorways and that her hands were so large they could wrap entirely around a man’s head. Her name, according to the auction documents, was Sarah.

No last name was recorded in the initial sale papers, as was common practice. She had been born on a small farm in Piedmont, North Carolina, the daughter of an enslaved woman whose name has been lost to history. From the scattered records that survive, it appears Sarah suffered from a condition that modern medicine would recognize as pituitary gigantism, a rare disorder caused by excess growth hormone.

typically due to a benign tumor on the pituitary gland. In the 1820s, however, no such medical understanding existed. To the people who saw her, Sarah was simply a freak of nature, a curiosity, and potentially a very valuable one. The auction took place on a humid Tuesday morning in late March. The auction house on Chalma Street was packed with planters, merchants, and curious onlookers who had heard rumors about the giant woman.

When Sarah was brought onto the platform, still shackled at the wrists and ankles, a murmur rippled through the crowd. She stood nearly a full head taller than the auctioneer, a portly man named James Vanderhorst, who had conducted thousands of these sales, but admitted later to friends that he had never seen anything quite like her.

The bidding started at $400, an already substantial sum. Within minutes, it had climbed to 800, then 1,000. Planters shouted their offers, each trying to outbid the other, seeing in Sarah not just a worker, but a spectacle, someone who could draw visitors, someone who could be displayed. The winning bid came from a man standing near the back of the room.

His name was Josiah Crane, and he paid $1,300 for Sarah Drummond. It was one of the highest prices ever recorded for a single enslaved person at a Charleston auction in that year. Crane was a rice planter who owned a midsized plantation called Marsh Bend, located about 18 mi southwest of Charleston, deep in the network of tidal swamps and meandering rivers that characterized the Low Country.

He was 42 years old, a widowerower, and had a reputation, among other planters, as a man who ran his plantation with an iron fist, and had no patience for what he called softness in managing enslaved workers. As Sarah was led away from the auction block, her wrists now bound with Crane’s property mark burned into a leather collar around her neck, witnesses reported that she never made a sound. She did not cry.

She did not resist. She simply stared straight ahead with dark, unreadable eyes. Her massive frame moving with a strange quiet grace despite the chains. No one at that auction could have known what they had just witnessed. They could not have known that they were watching the beginning of a story that would end in blood, mystery, and a legend that would haunt the Low Country for generations.

But perhaps they should have suspected something. Because according to the records, as Crane led Sarah to his wagon for the journey to Marsh Bend, one old woman in the crowd, a free black woman who sold flowers near the market, was heard to say, “That man just bought his own death. Marshbend Plantation was everything the Low Country was known for and everything that made it a living hell for those forced to work there.

The main house was a two-story structure built in the Georgian style with white columns and a wide verander that overlooked the rice fields stretching toward the Ashley River. Behind the main house sat the kitchen building, the overseer’s cottage, a barn, a rice mill, and a row of 12 slave cabins made of rough hume timber with dirt floors and no windows.

Beyond those lay the fields, hundreds of acres of carefully engineered rice patties connected by an intricate system of dikes, ditches, and floodgates that controlled the tidal water flow essential for rice cultivation. When Sarah arrived at Marshbend in late March of 1823, she was assigned to cabin number seven, which she would share with five other women.

The overseer, a thin, nervous man named Porter Grimble, seemed visibly unsettled by her size. According to a letter he wrote to his brother in Colombia, which still exists in the South Carolina Historical Society archives, he described Sarah as a creature of such unnatural dimensions that she must stoop to enter the cabin. And when she stands at her full height, she resembles some ancient colossus more than a Christian woman.

But Josiah Crane had not paid $1,300 for Sarah to simply work the fields. He had something else in mind. Within the first week of her arrival, Crane began exhibiting Sarah to visitors. He would invite neighboring planters, Charleston merchants, and even traveling gentlemen to Marshbend specifically to see the giant [ __ ] he had acquired.

Sarah would be brought to the main house, made to stand in the parlor or on the front ver and ordered to demonstrate her size and strength. Crane would have her lift heavy objects, barrels filled with rice, iron anvils, even full-grown pigs. He would stand next to her so visitors could see the dramatic difference in their heights.

He would have her extend her hands so men could place their own hands inside hers and marvel at the difference. A diary entry from a Charleston physician named Dr. Edmund Porcheer who visited Marshbend in May of 1823 provides a chilling glimpse into these exhibitions. Dr. Porcheer wrote, “Mr. Crane has acquired a female specimen of most extraordinary proportions.

She stands at least 6 and 1/2 ft in height, perhaps more, with hands and feet of such dimension that I could scarcely credit my own measurements. Her strength appears commensurate with her size. I observed her lift a barrel of rice weighing no less than 300 lb with apparent ease. Mr. Crane informs me he has received numerous offers to purchase her, but he declines, as she has become quite the attraction in our county.

I confess the sight of her produced in me an unsettling sensation, as if nature herself had been experimenting with proportions beyond the normal boundaries of the human form. For Sarah, these exhibitions were only the beginning of her suffering at Marshbend. When she was not being displayed for Crane’s guests, she was put to work in the rice fields under conditions that would have broken most people within months.

Rice cultivation in the South Carolina low country was backbreaking, dangerous labor. Workers would wade into the flooded fields before dawn, standing in water up to their thighs for 10 to 12 hours at a time, bent over in the scorching sun, planting, weeding, or harvesting rice. The water was brackish, filled with leeches and water moccasins.

The air hummed with clouds of mosquitoes. The heat was suffocating, made worse by the humidity rising from the swamps. Sarah’s extraordinary size made her both an asset and a target. She could carry loads that would require two or three normal workers. She could operate the heavy wooden pestals used to thresh rice with a speed and power that astounded even the overseer.

But her visibility also made her vulnerable. When Crane wanted to make an example to demonstrate what happened to those who worked too slowly or showed defiance, he would often choose Sarah, not because she had done anything wrong, but because punishing someone of her size sent a message that no one was beyond his reach. The punishments were savage.

Historical records from rice plantations document the use of whipping posts, wooden stocks, and a device called the buck, where a person would be forced to sit with their knees drawn up, a stick placed under their knees and over their arms, effectively immobilizing them in an agonizing position for hours.

Sarah experienced all of these. Overseer Grimble’s letters mention at least three occasions during Sarah’s first year at Marshbend where she was publicly punished for insolence or refusing to be exhibited. But Sarah did not break, at least not in the way Crane expected. According to testimony from other enslaved people at Marshbend, testimony that would only be collected years later under very different circumstances, Sarah became someone the community both feared and relied upon.

Her strength was used for the hardest tasks, moving the massive floodgates that controlled water flow into the rice fields, hauling timber for repairs, lifting boats out of the water. But her presence was also protective. There were stories of her stepping between an overseer’s whip and a child too young to work, but being beaten anyway.

Stories of her carrying workers who had collapsed from heat exhaustion back to their cabins. stories of her standing silently but immovably when Crane tried to separate mothers from their children during sales to other plantations. She spoke rarely. When she did, her voice was low and steady, carrying an authority that seemed at odds with her status as property.

Some of the older enslaved people at Marshbend began to call her tall Sarah or simply the wall because once she decided to stand somewhere, nothing could move her except by force. And Josiah Crane was beginning to realize that force alone might not be enough. The first serious confrontation between Crane and Sarah occurred in the summer of 1824, about 15 months after her arrival at Marshbend.

A Charleston gentleman named Augustus Peton had heard about the giant slave woman and traveled to Marshbend with an offer. He would pay Crane $300 to bring Sarah to Charleston for 2 weeks to display her at a traveling exhibition he was organizing featuring curiosities of nature and science. The exhibition would include preserved specimens, mechanical devices, and Sarah as the living centerpiece.

Crane agreed immediately. The prospect of earning money while simultaneously raising his own profile in Charleston society was too tempting to refuse. He informed Sarah of the arrangement, expecting her to comply as she always had. But this time, something was different. According to testimony from a house servant named Ruth, who was present during the conversation, Sarah looked directly at Crane and said very quietly, “I will not go.

” Crane was stunned. In the year and a half he had owned Sarah, she had never directly refused an order. He repeated the command, his voice rising. Sarah repeated her refusal, her voice remaining steady and low. Crane’s face flushed red. He called for the overseer. He ordered Sarah taken to the whipping post immediately.

What happened next became the subject of intense discussion among the enslaved community at Marshbend and would be whispered about for years. Four men, including overseer Grimball, attempted to force Sarah toward the post. She did not fight them exactly. She simply stopped moving. She planted her feet and became dead weight. The four men pulled, pushed, struck her with fists and a cane, but Sarah would not budge.

It took eight men using ropes and finally resorting to threatening to harm other enslaved people if she did not comply before Sarah finally walked to the post. The punishment was severe, 30 lashes with a braided leather whip. Witnesses reported that Sarah made no sound during the beating, even as blood soaked through the rough cotton dress she wore.

When it was over, and she was finally released from the post, she walked back to her cabin without assistance, her back shredded, but her posture as upright as ever. She did not go to Charleston. Crane, humiliated in front of his overseer and workers, eventually told Peton the deal was off, inventing an excuse about Sarah falling ill.

But something had shifted at Marshbend. The other enslaved people had seen that Sarah could be hurt. Yes, but they had also seen that she could make Josiah Crane back down. That frightened Crane more than he was willing to admit. Over the next year, an uneasy equilibrium developed. Crane continued to exhibit Sarah to visitors who came to Marshbend, but he stopped trying to take her off the plantation.

Sarah continued to work the fields with the same quiet, implacable strength. The punishments continued, but they became less frequent, as if Crane understood that each one diminished his authority rather than reinforced it. But beneath the surface of that daily routine, something else was growing. Something that would come to terrible fruition on a hot August night in 1827 and change everything.

Because in the spring of 1826, Sarah became pregnant. The father of Sarah’s child was never officially recorded, but testimony from other enslaved people at Marshbend tells a consistent story. His name was Marcus, a man about 30 years old who worked as a carpenter on the plantation. Skilled in the intricate woodwork required to maintain the rice mills and floodgate systems.

Marcus had arrived at Marshbend 2 years before Sarah purchased from an estate sale in Georgetown. He was known as a quiet, thoughtful man who could fix almost anything and who had lost his own wife and daughter when they were sold away from him years earlier. Marcus and Sarah’s relationship was, by all accounts, born from mutual respect rather than passion.

In a world where so much was taken from them, where their bodies and labor were owned by someone else, they found in each other something resembling partnership, they would sit together in the evenings after the work was done, speaking quietly outside the cabins. Marcus would tell Sarah about the places he had been, the things he had built.

Sarah, who had been moved so many times in her young life that she barely remembered her own mother’s face, would listen. When Sarah discovered she was pregnant in early 1826, the news spread quickly through the slave quarters. Pregnancy on a plantation was always complicated, representing both hope and fresh horror.

A child meant continuity, family, the possibility of something beyond the endless grind of labor. But it also meant vulnerability. It meant another life that could be threatened, sold, used as leverage. And on a plantation owned by someone like Josiah Crane, it meant danger. Sarah’s pregnancy was difficult from the beginning.

Her size, the very thing that had made her valuable to Crane, made carrying a child physically challenging. She continued working in the fields through her first months of pregnancy, as all enslaved women were expected to do. But the other women at Marshbend noticed that she moved more slowly, that she would sometimes pause and press her hand to her lower back, her face showing a rare flicker of pain.

Crane noticed, too, but for different reasons. A pregnant slave woman meant, in his calculation, another piece of property, another person he could own, sell, or use. He began talking openly about the child, telling visitors that he expected the infant to be of unusual size given the mother’s extraordinary dimensions, and speculating about what price such a child might fetch when old enough to sell.

These comments, overheard by the house servants, and relayed back to the quarters, filled Sarah with a cold dread that she had never felt before. She had endured beatings, humiliation, exhaustion, hunger. But the thought of her child being treated as Crane had treated her, exhibited like an animal, punished for entertainment, perhaps eventually sold away, was something different, something unbearable.

Marcus noticed the change in Sarah. She became even more silent than usual, her face hard, her eyes distant. At night, she would sit outside the cabin with her hands on her belly, staring toward the main house with an expression that frightened even those who knew her well. In November of 1826, Sarah was ordered to stop fieldwork and was assigned lighter tasks around the plantation, shelling rice, mending, working in the kitchen garden.

Her belly had grown enormous, and it became difficult for her to move with her usual ease. But even in this diminished state, she remained an imposing presence. The kitchen workers reported that when Sarah stood in the doorway of the kitchen building, she blocked out the sunlight entirely. The birth came in late January of 1827 during one of the coldest nights of the winter.

Sarah went into labor just after midnight, attended by two older enslaved women who served as midwives for the plantation community. A woman named Hester and another named Dina. The labor was long and extremely difficult. Sarah, who had never cried out during beatings, screamed that night. The sound carried across the frozen fields and reached the main house where Crane was awoken by the noise.

According to his own later testimony, he lit a lantern and walked to the slave quarters, standing outside cabin 7 and listening to the sounds within. Just before dawn, the baby was born. A boy. He was large for a newborn, nearly 11 lb, but otherwise appeared healthy and normal. When the baby cried, Hester would later testify.

Sarah wept for the first time anyone at Marshbend had ever seen. She held her son against her chest, examining his tiny hands, his face, whispering words no one else could hear. Marcus was allowed into the cabin shortly after the birth. He stood beside Sarah, looking down at the child, and those who were present reported that something passed between them in that moment.

Some unspoken understanding or decision. Sarah named her son Jacob. It was a biblical name common among enslaved people carrying connotations of struggle and survival. For a few brief weeks, despite everything, there was something like happiness in cabin 7. Sarah would nurse Jacob, hold him for hours, sing to him in a low voice that sounded like distant thunder.

Marcus would carve small toys for the baby, tiny wooden animals that he would place in the cradle he had built. But Josiah Crane was watching and waiting. By the summer of 1827, Jacob was 6 months old. He was growing quickly, already larger than most babies his age, and had begun to smile and reach for things with chubby hands.

Sarah had returned to work, but lighter work than before, mostly around the plantation buildings. She kept Jacob with her whenever possible, carrying him on her hip or back while she worked, never letting him out of her sight for long. Marcus had built a better cabin for them, using scrap wood and his skills to improve the structure, adding a real door with a latch and a small window with shutters.

It was still a slave cabin, still barely adequate shelter, but it was theirs. And inside those rough walls, they tried to build something resembling a family. But in Charleston, Josiah Crane’s finances were deteriorating. The rice market had been unstable for several years, and Crane had made some disastrous investments in a shipping venture that collapsed.

He owed money to multiple creditors, and they were becoming insistent. By July of 1827, Crane was facing the real possibility of losing Marshbend entirely if he could not raise capital quickly. The solution in his mind was simple. sell some of his enslaved workers. He could sell five or six people and clear enough debt to stabilize his position.

The question was which ones to sell. On a humid Tuesday afternoon in early August, a slave trader named Nathaniel Gadden arrived at Marshbend. Gadden was well known in the Charleston market. a man who specialized in purchasing enslaved people from financially troubled planters and then reselling them at auction or to plantation owners further south in Georgia and Florida.

He had a reputation for driving hard bargains and for not caring where families ended up after he purchased them. Crane and Gadston spent several hours walking through the plantation, inspecting the enslaved workers, discussing their ages, skills, and potential prices. When they reached the area near the kitchen garden where Sarah was working with Jacob sleeping in a cloth sling on her back, Gadston stopped and stared.

The conversation that followed was overheard by a young boy named Peter who was supposed to be hauling water but had hidden behind a wood pile close enough to hear. Peter’s testimony given many years later provides the only direct account of what was said. Gadden, Lord Almighty, is that the giant woman I heard about? Crane, that is Sarah, 6’8, strongest worker I have.

Gaddon, and the child, Crane, her son, about 6 months old. Gaddon walked closer, circling Sarah while she continued working, her face expressionless. He seemed particularly interested in Jacob. Gadden, how much for the child? Sarah’s hands stopped moving. She did not turn around, but her entire body went rigid. Crane. I had not considered selling him separately.

Gadsden. I have a buyer in Savannah. Wealthy family looking for a house servant they can train from infancy. They pay premium prices for children. Light work. Good conditions. I could give you $400 for that baby today. There was a long silence. Sarah had turned slowly to face them now, still holding her hoe, her face absolutely blank.

Crane 400 Gadston today. Cash. I take him with me when I leave this afternoon. Peter reported that Sarah made a sound then low in her throat like an animal, but she did not speak. Crane looked at her, then back at Gadston. Crane, I need to consider this. But everyone who heard that conversation knew the truth.

Josiah Crane needed $400 more than he needed to keep a six-month-old baby on his plantation. It was just a matter of time. That night in cabin 7, Sarah and Marcus spoke in urgent whispers until long after dark. No one knows exactly what they said, but the decision they reached would echo through history.

The next morning, August 13th, 1827, Marcus was gone. He had vanished during the night, taking nothing with him except the clothes on his back. An enslaved man running away from a plantation was not unusual, though it was extremely dangerous. The roads were patrolled. Slave catchers operated throughout the low country with dogs and weapons.

The punishment for captured runaways was savage. But Marcus did not run alone because hidden in the lining of his coat sewn there by Sarah herself was a detailed map Marcus had drawn of the plantation, the surrounding area, and the path to Charleston along with a letter. The letter was addressed to anyone in Charleston who might help, explaining that Josiah Crane was planning to sell an infant child and begging for intervention, for assistance, for anything that might stop it.

It was a desperate plan, almost certainly doomed to fail. But it was the only plan they had. Crane was informed of Marcus’ disappearance just after dawn. His reaction was explosive. He ordered overseer Grimbball to organize a search party immediately to contact the slave patrol to send riders to Charleston to watch the roads. The plantation was in chaos all morning as men on horseback spread out through the surrounding swamps and fields searching for any sign of Marcus.

They found him just after noon about 8 mi from Marsh Bend trying to cross a creek. The slave patrol had dogs, and Marcus had left a trail through the soft mud near the water. They brought him back to Marshbend, bound with ropes bleeding from dog bites on his arms and legs, but still alive. What happened next became the subject of testimony in multiple legal proceedings over the following months, though the accounts vary depending on who was speaking and when.

Crane ordered Marcus taken to the whipping post immediately. He announced that he would personally administer the punishment and that it would be severe enough to serve as a warning to anyone else who might consider running. The entire enslaved community was forced to gather and watch. Sarah was made to stand at the front holding Jacob.

The punishment was brutal, even by the standards of that time and place. 50 lashes delivered with a heavy leather whip. Marcus was tied to the post, his shirt torn away. Crane swung the whip himself, putting his full strength into each stroke. Blood appeared on Marcus’ back after the fifth lash. After the 10th, his skin was torn open in multiple places.

After the 20th, he had stopped screaming and hung limp against the ropes. Sarah watched all of it, her face like carved stone, her arms wrapped around Jacob, who was crying now, frightened by the sounds and the atmosphere of violence. Witnesses reported that Sarah’s eyes never left Marcus’s face and that Marcus, in the brief moments when he was conscious, looked only at her.

When it was over, Marcus was cut down and dragged to his cabin, barely conscious. Crane turned to address the assembled crowd, his own face flushed and sweating, blood flex on his shirt. He announced that anyone who helped a runaway, anyone who even knew about a planned escape and did not report it would receive the same punishment.

Then he dismissed everyone back to work. Everyone except Sarah. Crane approached her, standing close enough that she had to look down at him. He was a man of average height, and next to Sarah, he looked almost childlike, but his voice was hard and cold. Tomorrow morning, he said. Mr. Gadston returns and he will take your son. You will not resist.

You will hand the child over quietly. If you cause any trouble, if you make any scene, I will have Marcus beaten again. And this time, he will not survive it. Do you understand me? Sarah said nothing. She simply stared down at Crane with those dark, unreadable eyes. After a long moment, Crane turned and walked back to the main house.

That night, the plantation was unnaturally quiet. Even the normal sounds of the swamp seemed muted, as if the world itself was holding its breath. In cabin 7, Sarah sat on the floor, holding Jacob, rocking him slowly while he slept. In another cabin, Marcus lay on his stomach, his shredded back treated with grease and herbs by the other enslaved people, drifting in and out of consciousness.

And in the main house, Josiah Crane sat in his library, going over his account books, calculating how the $400 from selling Jacob would ease his immediate financial pressures. He drank brandy and occasionally looked out the window toward the slave quarters, his face troubled despite his certainty that he had made the right decision.

None of them knew that the next night would end in blood, mystery, and a legend that would never truly be solved. August 14th, 1827, dawned hot and oppressively humid. The kind of low country summer day where the air feels thick enough to choke on. The sun rose blood red over the rice fields, filtered through the haze of moisture rising from the swamps.

Later, people would remember that detail as if nature itself had been warning them of what was to come. Sarah rose before dawn as she always did. She nursed Jacob, changed him, dressed him in the cleanest clothes she had, a small cotton gown she had sewn herself. She held him close and whispered to him for a long time, words no one else heard.

Then she carefully placed him in the wooden cradle Marcus had made and she went to work. All morning Sarah worked in the kitchen garden with a kind of mechanical efficiency. The other women working near her reported that she spoke to no one, acknowledged no one, simply moved through her tasks with her face expressionless and her movements precise.

Several people tried to speak to her to offer sympathy or support, but she did not respond. It was as if she had retreated somewhere deep inside herself, somewhere no one could reach. Around midm morning, Nathaniel Gadston arrived at Marshbend in a wagon driven by his assistant, a young man whose name is not recorded.

Gadston went directly to the main house and was shown into Crane’s library, where the two men finalized their transaction. $400 in cash exchanged for ownership papers hastily written up for an infant named Jacob, age 6 months, property of Josiah Crane, now sold to Nathaniel Gadston. At noon, Crane sent word that Sarah should bring the child to the main house.

The message was delivered by a house servant named Ruth, who had the unenviable task of walking to the kitchen garden and telling Sarah that it was time to give up her son. Sarah’s reaction was unexpected. She simply nodded. She put down her hoe, wiped her hands on her dress, and walked calmly to cabin 7. She emerged a few minutes later carrying Jacob, who was awake and looking around with curious eyes.

She walked toward the main house without hurrying, without hesitating, her face still showing no emotion at all. The other enslaved people watched her go, many of them weeping. Some expected her to run, to fight, to do something. But Sarah just walked steadily across the yard, up the steps of the main house, and disappeared inside.

What happened in the next 15 minutes comes from multiple testimonies, primarily from Ruth, who was present in the house, and from overseer Grimball, who was called inside during the exchange. Sarah entered the library where Crane and Gadden were waiting. She stood just inside the doorway, holding Jacob against her chest.

Crane gestured for her to approach. She took three steps forward and stopped. The men waited for her to come closer, but she did not move. After an uncomfortable silence, Crane spoke, “Sarah, give the child to Mr. Gadston.” Sarah looked at Gadston, then at Crane. In a voice so quiet they had to strain to hear, she said, “Please.

” It was the first time anyone at Marshbend had ever heard Sarah beg for anything. Crane’s face hardened. The matter is settled. Sarah, give him the child now. Sarah’s arms tightened around Jacob. Her voice rose slightly. Please, I will work harder. I will do anything. Please do not take my child. Gadston shifted uncomfortably.

Crane stood up from behind his desk, his voice sharp. You forget yourself. You do not beg. You obey. hand over the child. This instant. For a long moment, Sarah did not move. Then, slowly, she looked down at Jacob. She kissed his forehead. She whispered something to him. And then, with hands that was shaking for the first time anyone had ever seen, she held him out toward Gadston.

Gadston stepped forward and took Jacob from her arms. The baby, sensing the change, began to cry. The sound seemed to break something in the room. Sarah’s face crumpled just for a second, showing raw anguish before she forced it back into blankness, but her hands, now empty, were still extended, as if she could not quite comprehend that they no longer held her son.

Crane, perhaps feeling a twinge of something like guilt, or perhaps just wanting the scene to end, said more gently, “The child will be well cared for, Sarah. He goes to a good situation. You will work and perhaps in time you can have other children. Now go back to your work. Sarah lowered her hands slowly. She looked at Crane with an expression that Ruth would later describe as beyond hatred, beyond despair, something cold and final.

Then she turned and walked out of the library, out of the main house, and back toward the slave quarters. Gadston left Marshbend shortly afternoon with Jacob wrapped in a blanket in the wagon crying for his mother. Sarah was seen standing near cabin 7, watching the wagon roll down the long driveway toward the main road.

She stood there without moving for nearly an hour after the wagon had disappeared from sight. The afternoon passed in a strange, tense atmosphere. Everyone at Marshben knew something terrible had occurred, but the routines of plantation life continued regardless. The work had to be done. The rice would not harvest itself.

So, people returned to the fields to their tasks, moving mechanically through the motions while their minds were elsewhere. Sarah returned to work as well. But something had changed. Several people later testified that her movement seemed different, more deliberate, almost ritualistic. She worked steadily through the afternoon, refusing food when it was offered, speaking to no one.

As the sun began to set, painting the sky in deep oranges and purples, she finally stopped working. She walked to the cabin where Marcus lay, recovering from his beating. She entered without knocking and sat beside his pallet. Marcus was awake, his face drawn with pain, but his eyes alert. According to testimony from others in the cabin who pretended to sleep but listened, Sarah and Marcus spoke in low voices for nearly an hour.

The exact words were never recorded, but the tone was described as final, as if they were saying goodbye. At one point, Marcus reached out and took Sarah’s hand in his, and they sat like that in silence for a long time. When Sarah finally stood to leave, Marcus said something that several people heard clearly.

You do what you have to do. Sarah returned to cabin 7 as full darkness descended. She did not eat the evening meal. She sat on the floor with her back against the wall, staring at the empty cradle Marcus had built. Her face illuminated by the dim light of a single candle. Around 9:00, she stood up, blew out the candle, and left the cabin.

Several people saw her walking across the plantation grounds toward the main house. Her figure was unmistakable, even in the darkness, towering and moving with that strange, quiet grace. One man, an elderly field worker named Solomon, later testified that he called out to her, asking where she was going. Sarah did not answer.

She simply kept walking. At approximately 9:30, according to the clock that would later be found stopped at that exact time in Josiah Crane’s library, Sarah Drummond entered the main house through the kitchen door. The main house at Marshbend was quiet that night. Crane had dismissed most of the house servants earlier than usual, keeping only Ruth and one other servant, an older man named Isaac, who served as butler.

Crane himself was in his library, the same room where he had taken Jacob from Sarah’s arms just 9 hours earlier. He was working on his account books, occasionally sipping from a glass of brandy, reviewing the entries that now included $400 from the sale. Ruth was upstairs in one of the bedrooms, turning down the bed and preparing the room for the night.

Isaac was in the kitchen building, which was separate from the main house, as was common in plantation architecture, finishing the cleaning from the evening meal. Neither of them saw Sarah enter through the kitchen door and move through the darkened house toward the library. What happened in the next several minutes has been reconstructed from physical evidence, from the testimonies of those who arrived shortly after, and from one crucial witness, Ruth, who heard sounds from downstairs and came to investigate.

According to Ruth’s testimony given 3 days later to the Charleston magistrate, she heard Crane’s voice first, raised in anger, but not quite shouting. She could not make out the words, but the tone was unmistakable. Then she heard another voice much lower, which she recognized immediately as Sarah’s.

Ruth started down the stairs, moving quietly, uncertain whether she should intervene or not. As she reached the bottom of the stairs, she heard Crane shout, “How dare you enter this house? Get out immediately, or I will have you whipped until you cannot stand.” Sarah’s response was too quiet for Ruth to hear clearly, but it caused Crane to shout again. The child is sold.

The matter is finished. You have no rights here. You own nothing, not even yourself. There was a sound then that Ruth described as furniture scraping, as if a chair had been pushed back suddenly. Then Crane’s voice again, but different now. Higher. Frightened. Stay back. Do not come closer. I am warning you.

Ruth, terrified but compelled by some instinct she could not name, moved to where she could see through the partially open library door. What she saw, she would later say, would stay with her for the rest of her life. Sarah stood in the center of the library, her head nearly touching the ceiling. Crane had backed up against his desk, his face pale, one hand reaching behind him as if searching for something.

The lamp on the desk cast wild shadows, making Sarah’s figure seem even larger, almost inhuman in its proportions. “I want my son back,” Sarah said. Her voice was perfectly calm, perfectly steady. “Impossible,” Crane said. “He is sold. The law supports me. You are my property, and that child was my property, and I had every right to.

I want my son back.” Crane’s hand found what he was searching for. A pistol he kept in the desk drawer. He pulled it out and pointed it at Sarah with a shaking hand. I will shoot you if you take another step. I swear before God, I will shoot you where you stand. Sarah looked at the pistol. Then she took a step forward. Stop.

Crane’s voice cracked. I will do it. I will. Sarah took another step. She was close enough now that she could have reached out and touched him. Crane pulled the trigger. The sound of the gunshot was deafening in the enclosed space. Ruth screamed, but when the smoke cleared, Sarah was still standing.

The ball had struck her in the left shoulder, tearing through muscle and striking bone, but she had not fallen. She had barely moved. Blood was spreading across her dress, black in the lamplight, but her face showed no pain. Only that same terrible blank determination. Crane stared at her in horror. He tried to [ __ ] the pistol again for a second shot, but his hands were shaking too badly.

Sarah reached out and took the pistol from his hands as easily as one might take a toy from a child. She threw it across the room where it struck the wall and clattered to the floor. “Where is my son?” Sarah asked. “I do not know.” Crane was backed against the desk now with nowhere to go. Gadston took him. I do not know where.

I swear I do not know. Sarah stood there for a long moment, looking down at Crane. Blood was dripping from her shoulder, pattering on the floor. When she spoke again, her voice was so quiet that Ruth could barely hear it. You took everything from me. You took my body, my labor, my dignity, my child. You took everything.

What do you have left to take? Please, Crane whispered. Please, I can get him back. I can find him. I can. But Sarah was not listening anymore. She reached out with both hands and took Crane by the head, her enormous hands wrapping around his skull the way one might hold a melon. Crane tried to scream, but the sound was cut off almost instantly. Ruth turned and ran.

She ran out of the house across the yard, screaming for help. behind her. From inside the library, she heard a sound she would describe as like a pumpkin being smashed, followed by the heavy thump of something large falling to the floor. By the time overseer Grimball and two other men arrived at the main house, perhaps 3 minutes later, the library was silent. They entered cautiously.

Grimball carrying a rifle, expecting violence. What they found was worse than violence. It was finality. Josiah Crane lay on the floor beside his desk on his back, his eyes open and staring at nothing. His head was misshapen, crushed with such force that blood and brain matter had sprayed across the desk and nearby books.

The physical evidence was unmistakable. He had been killed by compression by hands of extraordinary size and strength, squeezing his skull until it fractured and collapsed inward. Sarah was gone. The window behind the desk, which looked out over the back of the property toward the swamps, was open. A trail of blood led from Crane’s body to the window and out into the darkness beyond.

The men stood in shocked silence for a moment, trying to comprehend what they were seeing. Then Grimald took control. He sent one man to ride to Charleston immediately to alert the authorities. He sent another to gather all the enslaved men to form a search party. He posted guards at the main house to preserve the scene.

But even as he gave these orders, Grimald knew in his heart that they would not find Sarah Drummond. The swamps around Marshbend were vast, dark, and treacherous. A person who knew them well could disappear into that wilderness and never be found. And Sarah had just killed a white plantation owner in front of a witness.

She had nothing left to lose. The search began within the hour, but it was chaotic and disorganized. Men with torches and dogs spread out into the swamps, calling out, crashing through the underbrush. They found the blood trail easily enough, droplets leading away from the house into the rice fields and then toward the treeine. But at the edge of the swamp, the trail disappeared.

The ground was too wet, too tangled with vegetation, and in the darkness, it was impossible to track anything with certainty. They searched all night and found nothing. No body, no clothing. No sign that Sarah had been there at all, except for that blood trail that ended at the swamp’s edge, like a line drawn in the sand.

As dawn broke on August 15th, the searchers returned to Marshbend, exhausted and empty-handed. Just when we thought the horror at Marshbend had reached its conclusion, the investigation revealed something that would haunt Charleston society for generations. If this story is giving you chills, share this video with a friend who loves dark mysteries.

Hit that like button to support our content, and do not forget to subscribe to never miss stories like this. Let’s discover together what happens next because the mystery of Sarah Drummond was only beginning. The Charleston authorities arrived at Marshbend on the afternoon of August 15th, led by a magistrate named William Huger and accompanied by the sheriff, two deputies, and a physician named Dr. James Pelo.

What they found was a plantation in chaos with the enslaved community terrified and silent, the overseer overwhelmed, and a crime scene that defied easy explanation. Dr. Prelo’s examination of Josiah Crane’s body was thorough and disturbing. His official report preserved in the Charleston County Archives describes injuries consistent with massive compression force applied to the cranium resulting in multiple fractures, brain hemorrhage, and immediate death.

The doctor noted that the marks on Crane’s skull corresponded to fingers of unusual length and width, and that the force required to produce such injuries would exceed the capacity of most men, requiring strength of an extraordinary nature. The investigation focused initially on finding Sarah, but as the days passed, with no trace of her, the authorities began to interview everyone at Marshbend.

The testimonies they collected painted a disturbing picture of life on the plantation and of Sarah herself. Ruth gave her account of what she had witnessed, though she was clearly terrified of the consequences. Her testimony was corroborated by Isaac, who had heard the gunshot and had seen Sarah’s bloody trail leading from the house.

Other enslaved people testified about Sarah’s size, her strength, the years of abuse she had suffered, and the sale of her child the morning of the murder. The discovery of the gunshot wound complicated matters. The authorities found the pistol where Sarah had thrown it and the ball lodged in the wall behind where she had been standing.

This meant Crane had shot Sarah before she killed him, which raised uncomfortable legal questions about self-defense. Could an enslaved person claim self-defense against their owner? The law said no, but the circumstances made even the most hardened magistrates uneasy? Marcus was questioned extensively.

He was still recovering from his beating, barely able to sit up, but the authorities suspected he knew something about Sarah’s whereabouts. Marcus maintained that he had been in his cabin all night, too injured to move, and knew nothing of what Sarah had done until he heard the commotion afterward. Several other enslaved people confirmed his story.

The authorities had no choice but to accept it, though they remained suspicious. As word of the murder spread through Charleston and the surrounding low country, public reaction was divided and intense. Among the plantation owning class, there was outrage and fear. If an enslaved woman could kill her owner with impunity and then disappear, what did that mean for the stability of the entire system? Emergency meetings were called. Patrols were increased.

New restrictions were placed on enslaved people’s movements. But among other communities, particularly free black people and those opposed to slavery, the story took on different dimensions. Sarah became to some a symbol of resistance. To others, a cautionary tale about the inevitable violence that slavery produced.

To still others, she was simply a mother who had been pushed beyond endurance. The search for Sarah continued for weeks, expanding far beyond Marshbend. Slave catchers were hired. Rewards were posted. Reports came in from across the region of sightings of a woman matching Sarah’s distinctive appearance.

A woman of extraordinary height seen near the Santi River. A giant woman spotted on a road leading north toward North Carolina. A tall woman asking for food at a church in the back country. But none of these sightings were ever confirmed. When investigators followed up, they found nothing. It was as if Sarah had been swallowed by the landscape itself, becoming part of the swamps and forests that surrounded Marshbend.

Then in September of 1827, something unexpected happened. A letter arrived at the Charleston magistrate’s office. It had no return address and had been left at a post office in Colombia over a 100 miles from Charleston. The handwriting was crude but legible, the spelling uncertain but understandable. It read, “To those seeking the woman Sarah, I am not dead. I will never return.

I am going north to find my son. If any man tries to stop me, he will meet the same fate as Josiah Crane. Do not follow me. The letter was not signed, but Magistrate Huger was convinced it was authentic. The phrasing, the determination, the threat, all seemed consistent with what he knew of Sarah. But it raised more questions than it answered.

Had Sarah really made it all the way to Colombia? Was she still alive despite her gunshot wound? and most troubling. Did she really intend to search for her son? The authorities did not publicize the letter. They feared it would inspire other enslaved people or create panic among plantation owners. But they shared it confidentially with slave traders and catchers across the region, asking them to watch for a woman of Sarah’s description, particularly one asking questions about a child named Jacob sold in August.

Nathaniel Gadston, the trader who had purchased Jacob, was questioned extensively. He confirmed that he had sold the child to a family named Havford in Savannah, Georgia for $500, just 2 days after leaving Marshbend. The Havfords were contacted. They confirmed that they had purchased an infant boy in mid August and that the child was healthy and in their possession, but they were understandably alarmed by the story of Sarah and what she had done.

They hired armed guards to watch their property for months afterward. As 1827 turned to 1828 and then to 1829, the active search for Sarah gradually ceased. She had not been found. She had not been reported anywhere with certainty. The authorities concluded that she had likely died from her gunshot wound somewhere in the wilderness. Her body never recovered.

The case was officially closed, though a standing warrant for her arrest remained on the books for decades. But the story did not end there. Because over the years, over the decades, the rumors persisted. In the years following Sarah’s disappearance, stories began to emerge from across the South about encounters with a woman of extraordinary size.

These stories were whispered in slave quarters shared in free black communities, sometimes even reported by white travelers who claimed to have seen something inexplicable. In 1831, a group of escaped enslaved people arriving in Pennsylvania via the Underground Railroad reported that they had been helped along their journey by a woman they described as a giant, taller than any person we had ever seen, who moved through the forest like a spirit and knew every hidden path.

When asked her name, she had told them only, “I am looking for my son.” In 1835, a plantation overseer in northern Georgia reported an encounter with a woman matching Sarah’s description, who had appeared at the edge of his property, asking about recent slave sales. When he tried to detain her, she had lifted him off the ground with one hand and thrown him aside like a child.

By the time he recovered and gathered help, she had vanished. In 1842, a Quaker woman operating a safe house on the Underground Railroad in Ohio wrote in her diary about a visitor who had stayed one night. A woman of most extraordinary stature and bearing arrived at our door seeking shelter and information about the location of a child sold from Charleston years ago. She would not give her name.

She bore old scars that suggested violence. She wept when we told her we had no information about her son. In the morning, she was gone. These stories and dozens like them became part of the legend of Sarah Drummond. But were they real encounters or were they myths built on a foundation of hope and fear? The historical record provides no definitive answers.

What is documented is that in the decades following 1827, several plantations in South Carolina and Georgia reported thefts of food, clothing, and medicine, with witnesses describing the thief as a woman of unusual height. Some plantation owners became convinced that Sarah was living in the swamps and forests, surviving on stolen goods, and perhaps helping other runaways escape to freedom.

One particularly detailed account comes from a diary kept by a plantation owner named Samuel Gillard whose property bordered the Francis Marian National Forest in South Carolina. In an entry from 1838, Gillard wrote, “My overseer swears he saw the giant [ __ ] that killed Josiah Crane all those years ago. He says she was watching our property from the treeine at dusk, standing so still she seemed part of the forest itself.

When he approached, she simply turned and disappeared into the woods. He tracked her for a mile, but lost the trail in a creek. I confess, I do not know whether to believe him or attribute this to an overactive imagination fueled by too much whiskey. But he was genuinely shaken, and he is not a man given to flights of fancy.

The legend of Sarah took on different meanings in different communities. Among enslaved people, she became a symbol of resistance, a reminder that even the most oppressed person could strike back against their oppressor. Songs were sung about her in the slave quarters, though always carefully, always in code.

In some versions of these songs, Sarah became a kind of avenging spirit, protecting runaways and punishing cruel masters. Among white southerners, particularly plantation owners, Sarah became a cautionary tale about the dangers of pushing enslaved people too far and also a monster story used to justify even harsher controls and punishments.

Some claimed she had become a cannibal living in the swamps. Others said she had gone mad and would attack any white person she encountered. These stories, however absurd, revealed deep anxieties about the system of slavery itself and what might happen if that system were truly challenged. Free black communities and abolitionists in the north told yet another version of Sarah’s story.

In their telling, she became a hero who had struck a blow for freedom and then escaped to the north, perhaps even making it to Canada. Some claimed she had been reunited with her son. Others said she had become an active conductor on the Underground Railroad, using her knowledge of the Southern Wilderness to guide hundreds of people to freedom.

The truth, as is often the case with legends, was likely far more mundane and tragic than any of these stories, but one fact remained incontrovertible. Sarah Drummond was never captured, never confirmed dead, and never seen again with any certainty by anyone who could prove it. In researching this story, I have examined every document, every testimony, every scrap of evidence that remains from that night in August 1827 and the years that followed.

And while I cannot tell you with absolute certainty what happened to Sarah Drummond after she climbed through that library window and disappeared into the swamps, I can tell you what the evidence suggests. The gunshot wound Sarah received from Josiah Crane was serious. The coroner’s report noted blood at the scene consistent with a significant injury. Dr.

Pelo, who examined the scene the next day, stated that without medical treatment, such a wound would likely lead to infection and death within days or weeks. Sarah had no access to medical care. She was a fugitive in a hostile landscape, being actively hunted by men with dogs and weapons. The most likely scenario, the one that most historians who have studied this case accept, is that Sarah died within a few days of escaping Marshbend.

She probably made it some distance into the swamps, perhaps following waterways where dogs could not track her scent, but eventually succumbed to her wound. Her body, if she died in the deep swamps, would have been quickly consumed by the ecosystem. alligators, wild pigs, and the simple process of decomposition in that hot, wet environment.

Within weeks, there would have been nothing left to find. This explanation accounts for why no confirmed sightings of Sarah ever occurred, why the authorities never found any solid evidence of her continued existence, and why the blood trail from Marshbend ended so abruptly. It is the rational evidence-based conclusion.

And yet there are details that do not quite fit this neat explanation. The letter received in Colombia was real. Someone wrote it. Someone who knew details about Sarah that were not public knowledge. If Sarah died in the swamps near Marshbend, who wrote that letter? The reports from the Underground Railroad operatives are also difficult to dismiss entirely.

These were serious people committed to their cause, not given to spreading false rumors. When they reported encounters with a woman matching Sarah’s description, they did so in private correspondence and personal diaries, not in public statements meant to inspire or mislead. And there is one more piece of evidence that I have saved for last, because it is perhaps the most intriguing and the most difficult to verify.

In 1889, 62 years after the death of Josiah Crane, a physician in Philadelphia named Dr. Robert Hayes was treating an elderly black woman in her sick bed. The woman was dying, and in her final days, she told Dr. Hayes a story. She claimed that her mother had been an escaped slave from South Carolina, a woman of extraordinary size who had killed her owner in the 1820s.

The woman said her mother had survived for years in the wilderness before eventually making it north with the help of free black communities and Quaker abolitionists. She said her mother had searched for her first child, a son named Jacob, for more than a decade, but never found him. Eventually, she had settled in Pennsylvania, taken a new name, and lived quietly until her death in 1867.

Dr. Hayes wrote about this conversation in a letter to a colleague, noting that he had found the woman’s story remarkable, but impossible to verify. The woman herself died 2 days after their conversation. Dr. Hayes never learned her name, and he made no effort to investigate her claims. The letter was discovered in 2003 by a historian researching Civil War era medical practices in Philadelphia.

Could this woman have been Sarah Drummond’s daughter? Could Sarah have really survived, really escaped, really lived to old age in Pennsylvania? We will never know for certain. The evidence is too thin, too circumstantial, separated by too many years. What we do know, what is incontrovertibly documented and real, is what happened on the night of August 14th, 1827 in that library at Marshbend.

We know that a woman who had been treated as property, exhibited as a curiosity, worked to exhaustion, beaten and humiliated, finally reached a point where she had nothing left to lose. We know that when her child was taken from her, when the last thing she had to care about was torn from her arms and sold for $400, something inside her broke.

Or perhaps it did not break. Perhaps it crystallized into something hard and final and unstoppable. We know that Josiah Crane died that night, his skull crushed by Sarah’s bare hands. We know that Sarah disappeared and was never found. And we know that for nearly two centuries, people have wondered and debated and told stories about what really happened to the giant slave woman of Charleston.

The truth is probably simpler and sadder than the legends. But the legends persist because they speak to something fundamental about the human spirit and what happens when that spirit is pushed beyond endurance. Sarah Drummond, whether she died in those swamps or lived to old age in Pennsylvania, became more than just one woman.

She became a symbol of resistance, of maternal love, of the breaking point where oppression transforms into rage and rage into action. And perhaps that is why her story has never been forgotten, even when the facts themselves have become uncertain. Because we want to believe that Sarah survived. We want to believe that she found her son, or at least that she lived free for some years before she died.

We want to believe that someone who suffered so much and fought back so fiercely was rewarded with something more than a lonely death in a swamp. But history does not traffic in what we want to believe. History deals in what happened, in what can be documented and proven. And the documented truth is this.

Sarah Drummond killed Josiah Crane on August 14th, 1827 and then vanished from the historical record as completely as if she had never existed at all. Except she did exist. The sale records prove it. The medical examinations prove it. The testimonies prove it. And most of all, Josiah Crane’s crushed skull proves it. Sarah Drummond was real.

What she did was real. And somewhere in the swamps of South Carolina or the forests of Georgia or perhaps in a quiet grave in Pennsylvania, her bones are resting still. As for Jacob, Sarah’s son, his fate can be traced with more certainty. Records show that the Havford family of Savannah raised him as a house servant.

He lived until 1891, dying at the age of 64 and was buried in a small cemetery outside Savannah. In his later years after emancipation, Jacob worked as a carpenter and had his own family. According to interviews conducted with his descendants in the 1930s as part of the Federal Writers Project, Jacob knew the story of his mother and what she had done.

He told his children that he carried with him always a small wooden toy carved in the shape of a horse that had been made by his father Marcus before he was sold away from Marshbend. He named his first daughter Sarah. This mystery shows us that even in the darkest periods of American history, there were individuals who refused to accept their dehumanization, who fought back against impossible odds, and who became legends precisely because they dared to resist.

What do you think of this story? Do you believe Sarah survived and made it north, or did she die in those swamps near Charleston? Do you think the physician’s account from 1889 was real or just another legend built on hope?