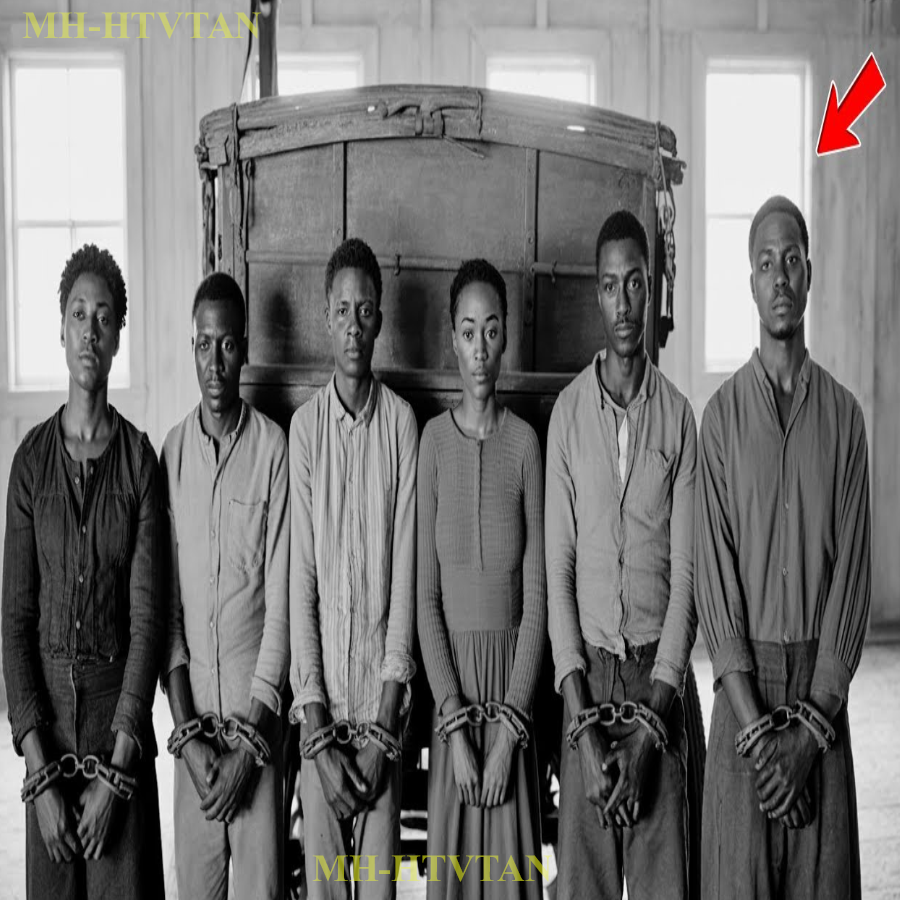

In case you haven’t joined our community, kindly do because interesting stories that never made it to the public has been revealed in our community platform. Let’s begin our story. While Master Cornelius Blackwood and his guests celebrated in the main hall of Willowre plantation with Kentucky bourbon and Cuban cigars, commemorating the purchase of 15 more slaves and discussing record cotton profits for the season of 1857, no one noticed the 38-year-old woman silently gliding through the pine woods surrounding the property, methodically opening the six reinforced wooden cages she had built over the past 8 months.

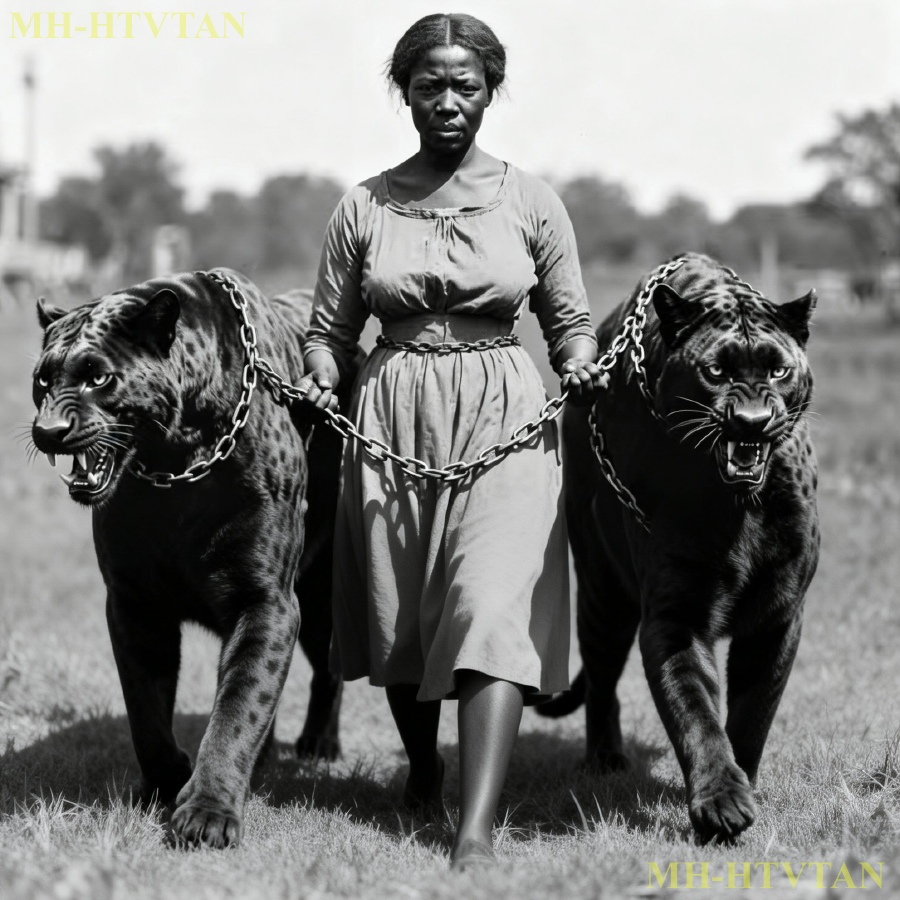

Her name was Manurva Hall, enslaved for 22 years, officially listed in the plantation records as animal keeper and pest hunter, a title that masked her true specialty, tamer of wild predators. Daughter of a captured Igbo priestess who whispered ancestral secrets about the language of great cats.

Manurva possessed a gift that white men never understood. The ability to communicate with panthers, cougars, and lynxes through sounds, gestures, and pure energy. For years she kept this knowledge hidden, watching, learning, waiting, until February of 1857 when Master Blackwood raped her 14-year-old daughter, patients, and then sold her pregnant to a Savannah brothel to avoid problems on the plantation.

That night, something ancient and furious awakened in Manurva’s heart. She did not plan escape. She planned devastation. For eight months, she captured six wild cats, two black panthers, three young cougars, and one adult lynx from Georgia’s deep forests. She fed them with meat and rage. She trained them with infinite patience.

And on the night of October 22nd, 1857, while six white men laughed and drank, Manurva Hall opened the cages and whispered a single command in her mother’s ancient tongue. What happened that night transformed Manurva into the most feared and mythical figure in Georgia slavery history, the panther queen, the woman who proved that even the wildest beasts would obey an enslaved black woman before bowing to their supposed masters.

But it all began 8 months before when Manurva Hall was still just another enslaved woman trying to survive in Burke County, Georgia. In the heart of the plantation belt that made white men rich and black people property, Willowre plantation sprawled across 2,300 acres of prime Georgia land 20 mi west of Augusta in Burke County.

The property had belonged to the Blackwood family since 1798, passed down through three generations of slaveholders who built their fortune on cotton and cruelty. In 1857, the plantation held 143 enslaved people, making Cornelius Blackwood one of the wealthiest men in the county. The big house stood three stories tall, white columns gleaming in the Georgia sun, surrounded by magnolia trees and manicured lawns that slaves watered daily, even during droughts.

Behind the facade of southern gentility lay a system of systematic brutality that would make demons weep. The plantation operated like a small kingdom with its own rigid hierarchy. At the top sat Master Cornelius Blackwood, 47 years old, a man whose education at Yale and trips to Europe did nothing to temper his belief in white supremacy.

He justified slavery through elaborate theological and philosophical arguments he discussed at dinner parties, quoting Greek philosophers and southern ministers who preached that slavery was ordained by God. Cornelius was methodical in his cruelty. He kept detailed records of punishments administered, believing the documentation made the system more civilized.

His ledger listed 217 whippings in 1856 alone, each one numbered, dated, and annotated with the alleged offense. He stood 6’2 in tall, wore expensive suits imported from Charleston, and maintained a library of 3,000 books that no slave was permitted to touch under penalty of having their fingers broken.

His wife, Mistress Elellanena Blackwood, 39 years old, came from old Savannah money. She maintained the fiction that she was a gentile southern lady of refinement, playing piano in the parlor and organizing church socials. But in the privacy of the big house, Elellanena was perhaps more sadistic than her husband. She specialized in psychological tortures, separating mothers from children as punishment for minor infractions, forcing enslaved women to watch as their children were sold, smiling sweetly while destroying families. She kept a collection of

silver implements in her dressing room, small knives, pins, heated combs that she used to discipline house slaves for imagined sllights. Eleanor particularly targeted young enslaved women whom she viewed as threats and rivals. Her jealousy was legendary and lethal.

Theoverseer was a man named Silas Crowe, 34 years old, poor white trash from upount, who clawed his way to his position through enthusiastic violence. Silas had been hired four years prior after the previous overseer was deemed too soft for not achieving cotton quotas. Where the previous man had used the whip sparingly, Silas wielded it with artistic cruelty.

He carried a braided leather bullhip 12 ft long, custommade in Augusta, with steel tips woven into the end. He named it obedience, and boasted that it had tasted the blood of 67 different slaves. Silas stood 5’9 in, thin and wiry, with gray eyes that reflected nothing human. He chewed tobacco constantly, spitting brown juice as he walked the fields, watching for any slave who straightened their back for a moment’s rest.

Below Silas in the hierarchy were two drivers, enslaved men promoted to positions of power over their fellow slaves. The head driver was a man named Josiah, 41 years old, who had traded his soul for slightly better food and permission to sleep in the big house basement instead of the quarters. Josiah carried a hickory stick and used it freely, believing that harsh discipline of other slaves would protect his own precarious position.

The second driver was Marcus, 28, who had been promised his freedom after 10 years of service. A promise everyone except Marcus knew would never be kept. Then there was Dr. Ambrose Whitfield, 53, who visited the plantation twice monthly to tend to the white family and conduct medical experiments on enslaved bodies. Whitfield believed black people felt less pain than whites and used this convenient fiction to justify procedures performed without anesthesia.

He had tested this theory 73 times as documented in his personal journal which he planned to publish in a medical journal in Charleston. His specialty was gynecological experimentation on enslaved women. operations he performed in a shed behind the big house while their screams echoed across the plantation.

This was the world Manurva Hall had endured for 22 years. And every single one of these men would die screaming before the moon set on October 22nd. But before we understand the magnitude of the vengeance that was coming, we must understand who Manurva truly was. Not just what slavery tried to make her. Manurva had not been born into slavery.

She arrived in America at age 16 in 1835 on the slave ship Nightingale out of Calabar. Her African name was Em, which meant peace in the Aibio language. Her mother, Adiaha, was a high priestess of the EC society, a secret spiritual tradition that honored the leopard as sacred messenger between worlds. Adia had taught young Ems, how to read animal tracks, how to distinguish poisonous plants from healing ones, how to move through forest without disturbing the spirits that dwelled there.

Most importantly, Adyah had passed down the ancient knowledge of leopard speaking, a practice that required absolute mental discipline and spiritual purity. Only a handful of women in each generation possessed the gift. Imam learned by watching her mother commune with the leopards that roamed the forests near their village. She learned the difference between the warning growl and the greeting purr, between the hunting call and the mating song, between the sounds that meant come and those that meant kill.

By age 14, Imm could bring three leopards to her side with nothing but a specific whistle and a certain scent she wore. The leopards recognized her as kin, as something other than prey or threat. They rubbed against her legs like house cats, leaving their scent on her skin. Then the slavers came. British traders working with collaborating tribal chiefs raided her village at dawn.

Emim watched her mother cut down with machetes as she tried to protect the sacred grove. She watched her younger brother, only 8 years old, clubbed to death because he was too small to be worth the trouble of transport. She and 47 others from her village were chained together and marched 200 m to the coast. By the time they reached the slave fort at Calabar, only 29 remained alive.

The middle passage took 63 days. Mm spent those days in darkness below deck, chained so tightly she couldn’t move, lying in human waste, listening to people die around her. She survived by going somewhere else in her mind, back to the forest, back to her mother’s teachings, back to the feeling of leopard fur under her palms.

She whispered the old prayers even when her lips cracked and bled from dehydration. She kept the knowledge alive even as her body withered. She arrived in Charleston in November of 1835. The auction took place on a raised wooden platform while white men prodded her body like livestock, checking teeth and limbs. A slave trader named Nathaniel Morse bought her for $400.

He renamed her Manurva because he thought it sounded more civilized than her African name. She became his property, less human than his horse, more valuable than his furniture. For 6 months, Morsekept her locked in a transition house in Charleston, where newly arrived Africans were broken and trained in English and obedience.

The methods included starvation, beatings, and something Morse called seasoning, systematic rape designed to destroy spirit and identity. Manurva survived by disappearing inside herself. She learned enough English to follow commands. She kept her knowledge of leopard speaking buried so deep even she almost forgot it existed and she waited.

Patience was a lesson the leopards had taught her. In March of 1836, Cornelius Blackwood purchased her at auction in Augusta for $650. Impressed by her physical strength and the fact she’d survived the middle passage without apparent damage, he brought her to Willowre Plantation and assigned her to fieldwork, cottonpicking from sun up to sundown, backbreaking labor that destroyed bodies by age 30.

But Manurva was strong. Her mother’s bloodline carried power that slavery could not fully extinguish. For 22 years, she survived. She worked the fields in blazing Georgia heat. She picked cotton until her fingers bled. She endured whippings, starvation, and humiliation. At age 21, she was forced into a breeding relationship with a man named Thomas, the master’s way of increasing his slave holdings.

She gave birth to four children. The first, a son named Joseph, was sold at age 8 to a sugar plantation in Louisiana. Manurva held him as he screamed and begged not to go, then watched the wagon carry him away, knowing she would never see him again. The second, a daughter named Grace, died of fever at age three because Dr.

Whitfield refused to waste medicine on slave children. The third, another son named Samuel, was killed at age 12 when an infected cotton hook wound went untreated. And the fourth, her precious patients, was born in 1843. the one remaining light in Manurva’s world of darkness. Patience grew up beautiful. At 14, she had her mother’s high cheekbones and her grandmother’s liquid brown eyes.

She was gentle, sweetnatured, always humming spirituals while she worked in the big house as a maid. Manurva taught her daughter the old ways in secret whispers, not the leopard speaking, for that gift had not passed to patience, but other knowledge, how to find north by stars, how to recognize edible plants, how to read signs of danger, how to survive.

Manurva had given up hope of freedom long ago. She lived only for patience. Each night after 18 hours of labor, she would sneak to the big house kitchen where patients slept on a pallet and hold her daughter while teaching her songs in the old language. Manurva dreamed of nothing beyond keeping patients safe, fed, alive.

It was a small dream for a woman whose mother had been a priestess, but slavery ground down even the strongest spirits. Manurva had learned not to hope for more than survival. Then came the night of February 14th, 1857, Valentine’s Day. The night everything that remained human in Manurva Hall died, and something far more dangerous was born.

Master Blackwood had been drinking heavily. His wife Elellanar had traveled to Savannah to visit her sister, leaving him alone in the big house with only the house slaves for company. Around 10:00 that night, he summoned patients to his study to refill his bourbon decanter. What happened in that room would haunt Manurva’s nightmares for the rest of her life because she heard everything.

Manurva had been working late in the kitchen, preparing dough for tomorrow’s bread. The kitchen was adjacent to the master’s study, and the walls were thin. She heard patients enter. She heard Blackwood’s slurred voice asking the girl to come closer. She heard Patience’s soft, confused response. Then she heard the sharp sound of the lock clicking.

What followed was 27 minutes of hell. Manurva listened to her daughter’s screams, muffled by Blackwood’s hand over her mouth. She listened to furniture crashing. She listened to the rhythmic creaking and patience’s sobbing please. She stood frozen in the kitchen, a knife trembling in her hand, knowing that if she burst through that door, she would kill him and be hanged within hours, and then there would be no one to protect patients afterward.

So she stood there and listened and died inside. When Blackwood finally unlocked the door and shoved patients out, the girl stumbled into the kitchen, barely able to walk, blood streaming down her thighs, her dress torn, her eyes vacant. Manurva held her daughter while patients shook violently, going into shock. She whispered old prayers in her mother’s tongue, prayers for protection that came 27 minutes too late.

For 3 weeks after that night, patients did not speak. She performed her duties mechanically. A ghost wearing her daughter’s face. Manurva watched her with a grief so profound it felt like physical wounds. And she waited because there was nothing else she could do. In the world of slavery, black women had no recourse, no justice, no protection.

Masters could dowhatever they wanted to enslaved women’s bodies, and the law called it property rights. Then in early March, patients began vomiting every morning. By mid-March, it was clear she was pregnant. By late March, Elellanena Blackwood had returned from Savannah and noticed the girl’s condition. Elellanena immediately understood what must have happened and was enraged, not at her husband, but at patience for tempting him.

On March 28th, Manurva was working in the vegetable garden when she saw Silus Crowe leading patients toward the front gate where a closed wagon waited. Manurva dropped her hoe and ran, not caring about the consequences. She reached them just as a slave trader named Rufusqincaid was inspecting patients like livestock. This one’s young and healthy despite the condition was saying running his hands over patients’s body while the girl stood trembling.

Madame Dupri’s establishment in Savannah will take her. Pregnant girls fetch good money in the brothel. Certain clients prefer that. I’ll give you $800. Manurva grabbed her daughter, pulled her close. No, please, Master Blackwood, please don’t do this. She’s just a child. Please. Blackwood stood on the porch, watching with cold detachment.

Should have thought of that before she threw herself at me. Can’t have her here breeding bastards and giving my wife grief. Business is business, Manurva. You know that. She didn’t throw herself at you, Manurva screamed, losing all caution. You raped her. She’s 14 years old. You raped my baby. Silus Crow’s whip cracked across Manurva’s back, opening a gash through her dress.

She didn’t even feel it. She clung to patience with desperate strength. “Mama, mama, don’t let them take me.” Patience sobbed, the first words she’d spoken in 3 weeks. “Please, Mama, I don’t want to go. Please.” It took Silas, Josiah, and Marcus combined to pry Manurva’s hands loose from her daughter.

She fought with inhuman strength, scratching, biting, screaming in English and the old tongue. She fought until Silas clubbed her across the back of the head with his whip handle, sending her crashing to the dirt. Through blurred vision, she watched Rufusqincaid drag patients into the wagon while her daughter reached back toward her. Mama, mama, help me.

Mama. The wagon door slammed shut. Concincaid climbed onto the driver’s seat, counted out $800 in bills, and handed them to Blackwood. The master pocketed the money without expression. The wagon began rolling down the long drive toward the main road. Manurva lay in the dirt, blood streaming from her head, and watched her daughter disappear.

She heard patients’s screams growing fainter as the wagon carried her away toward Savannah, toward a life of horror that would end with patients dead from disease or violence within a year. Her baby still born or murdered at birth. Manurva knew the statistics. She’d seen it happen to dozens of other girls. Something snapped inside her then, not broke. Broke implies pieces remain.

What happened to Manurva was more fundamental. Every molecule of who she had been realigned into something new. The woman lying in the dirt was no longer human in any recognizable sense. She had become something the slaveholders should have feared far more than any uprising or escape attempt. She had become vengeance made flesh.

The other slaves helped her to the quarters that night. They cleaned the wound on her head, whispered sympathy, tried to comfort her, but Manurva didn’t cry, didn’t speak. She lay on her pallet and stared at the ceiling while something ancient stirred in her blood. Her mother’s knowledge, dormant for 22 years, woke fully.

The leopard speaking her grandmother had mastered passed through bloodlines, rose to the surface of her consciousness, like an answer to a question she’d been asking her entire enslaved life. If you’re feeling rage right now, you should. This was real. This happened on American soil in American history. These horrors were legal, protected by law, sanctioned by church and state.

Manurva’s story is not unique. It happened to thousands of enslaved mothers, thousands of enslaved daughters. The only unusual thing about Manurva is what came next. Because 3 days after they took patience, Manurva walked into the Georgia wilderness and began hunting. The forests of Burke County, Georgia in 1857 were wild and vast.

Beyond the cultivated fields of the plantations lay thousands of acres of untamed woodland, longleaf pine forests, cypress swamps, thick palmetto understory, and the savannah river bottomlands where creatures from another era still thrived. The cats of Georgia were smaller than the African leopards Manurva’s mother had communed with, but they were no less deadly.

Black panthers prowled the deepest swamps. Cougars roamed the river bluffs. Bobcats and lynxes hunted through the pine baronss. These were apex predators, normally impossible to approach, much less capture or train. But Manurva had knowledge that went back 50 generations.and she had nothing left to lose except the revenge that now sustained her.

She began by requesting permission to hunt for the plantation, asking if she could trap small game and catch pests that destroyed crops. Blackwood agreed immediately. Pleased to have free meat and thinking this would keep Manurva occupied and broken, he assigned her the official role of pest hunter, gave her access to traps and tools, and granted her freedom to move through the woods during evening hours after fieldwork ended.

He thought he was using her grief to exploit more labor. He had no idea he had just given her the tools and opportunity for his own destruction. For the first month, Manurva legitimately hunted small game. She brought back rabbits, psums, and the occasional deer. She learned the forest again, reacquainting herself with the patterns of wild things.

At night, she walked deeper than anyone else dared, following signs only she could read. She listened to the night sounds, distinguishing between species, understanding the language of the hunt, and she began to remember exactly who she had been before they renamed her and chained her. In the fourth week of April, she found the first panther.

It was a young male, perhaps 3 years old, lean and hungry from a hard winter. Manurva tracked him for three days, learning his patterns, understanding his territory. Then she laid a trap, not the steel kind that broke bones, but something more sophisticated. She killed a deer, gutted it, and placed the carcass in a clearing, then climbed a tree and waited.

When the panther came at dusk to feed, Manurva began to sing, not in English, not in any language white men would recognize. She sang in the ancient ec tongue the words her mother had taught her. The sounds that meant you are seen, you are respected, you are kin. The panther froze midbite, ears swiveling toward the sound. Manurva kept singing, pitch perfect, letting the sound roll through her throat in patterns that mimicked the big cat’s own vocalizations.

Slowly, carefully, she climbed down from the tree while never breaking the song. The panther watched her approach, his tail twitched, muscles bunched, ready to flee or attack, but Manurva knew the precise moment to drop her pitch, to add the rumble that meant, “I am not prey. I am pack.

” She moved with liquid grace, not like the jerky, frightened movements of humans, but with the deliberate confidence of another predator. She knelt 10 ft from the cat, still singing, and placed her hand flat on the ground. The panther stared at her for a full minute. Then slowly, impossibly, he lowered his head and approached. He sniffed her outstretched hand.

His rough tongue licked her palm once, and then he rubbed his massive head against her shoulder, marking her with his scent, accepting her into his world. Manurva wept then for the first time since they took patience. She wrapped her arms around that wild thing and felt connection to something pure and free and deadly.

The panther stayed with her for an hour before melting back into the forest. But he would return because Manurva had spoken to something deeper than training or domestication. She had spoken to the ancient contract between her people and the great cats, a bond that predated civilization itself. Over the next two months, she found five more.

Two more panthers, a mated pair, living deep in the Savannah River swamps. Three young cougars, siblings, hunting the pine baronss north of the plantation, and one magnificent lynx scarred from fights, intelligent eyes that seemed to understand exactly what Manurva was asking. Each one she contacted using the old methods. Each one she brought into the circle through song, scent, and the subtle energy that connected predator to predator.

She did not cage them at first. She simply established relationship, visiting each one daily, bringing food, singing the songs, reinforcing the bond. She learned their personalities. The lead panther was aggressive and territorial, perfect for close quarters combat. The panther pair were coordinated hunters who moved like synchronized shadows.

The cougars were young and eager, willing to follow direction, hungry for approval, and the lynx was a stone cold killer, patient and merciless. By June, she had earned their trust completely. That’s when she began the real training. Manurva had built the cages deep in the forest, 3 mi from the plantation, in a ravine thick with private hedges and covered by a canopy so dense sunlight barely penetrated.

The cages were not prison cells, but training grounds, large enough for the cats to move freely, strong enough to contain them when necessary. She lined each cage with soft pine needles and provided water from a nearby spring. She wanted them comfortable, not traumatized. This was partnership, not enslavement. The training itself was complex.

First, she had to teach the cats to respond to specific sounds. A low whistle meantgather. A sharp click meant hunt. A long vowel sound meant hold position. She practiced these commands during feeding, rewarding instant obedience with fresh meat. The cats were intelligent and food motivated, learning quickly.

Second, she had to teach them to tolerate cages without panicking. She did this gradually, leaving cage doors open at first, placing food inside, letting them come and go freely. Only after weeks of this did she begin closing doors for short periods, always accompanied by her calming presence and songs. Third, and most difficult, she had to train them to attack specific targets while ignoring others. This required extreme precision.

She made scarecrows dressed in clothing stolen piece by piece from the big house, Blackwood shirts, Silus Crow’s pants, Elellanena’s dresses. She soaked these clothes in the actual scents of her targets, collecting them secretly over months. Sweat stained collar, blood spotted cuff. The cats learned to associate these scents with the attack command, but she also needed them to ignore the scent of slaves.

So she collected clothes from the quarters, surrounded the scarecrows with these alternate scents, and trained the cats to distinguish between attack this and protect this. It took 3 months of intensive daily work. By September, the cats could differentiate targets with terrifying accuracy. She tested the training with a live trial.

She captured a wild boar, dressed it in a shirt stolen from Josiah the driver, and released it in a clearing with three of the cougars. She gave the attack command. The cougars brought down the boar in 12 seconds, going straight for the throat with coordinated precision. Then she released a goat wearing a shirt from the slave quarters and gave the same command.

The cougars circled the goat, but never attacked, merely hering it back toward Manurva. Perfect. They were ready. The final phase of preparation was psychological, and it was the darkest part of Manurva’s work. She deliberately fed the cats less in the weeks before the planned attack, keeping them hungry, but not weak. She also began introducing them to human blood.

Small amounts at first mixed with meat, gradually increasing the concentration until they associated the scent with feeding. She knew from her mother’s teaching that cats who tasted human blood even once became far more dangerous, far more willing to see humans as prey rather than threat. This is the part that should disturb you most because Manurva was not acting out of sudden rage or temporary insanity.

She was planning cold, calculated, precision murder over 8 months of patient work. She was weaponizing nature itself against the people who had taken everything from her. And she was doing it with the calm efficiency of someone who had finally found her purpose. During these months of preparation, life at Willamir continued as normal.

Manurva worked her fields, kept her head down, played the role of the broken slave, mourning her daughter. She was the perfect image of defeated submission. Master Blackwood pointed her out at dinner parties as an example of successful seasoning. That woman lost a child recently, but see how she continues to work without complaint.

That’s the proper attitude for a slave. No one suspected what she was doing in the forest each evening. No one noticed the scratches on her arms from training the cats, assuming they were from briars. No one paid attention when she hummed spiritual songs with unusual rhythms during fieldwork. Songs that were actually practiced for the calling sounds she would use to direct the cats during the attack.

Silus Crow did notice that Manurva seemed to disappear into the woods each evening, but he assumed she was trapping game or perhaps meeting a man. He watched her sometimes, considering whether to follow and punish her for unauthorized absence, but she always returned before curfew with trapped rabbits or useful information about crop pests, so he let it go.

That decision would cost him his life. By early October, everything was ready. The six cats responded to her commands with perfect obedience. They were hungry, aggressive, and imprinted on the target’s sense. The cages were positioned within half a mile of the big house, close enough to reach quickly, but far enough to remain undiscovered.

Manurva had mapped out every detail. The route from the cages to the big house, the positions where each cat would be released, the order of attacks, the backup plans if anything went wrong. There was only one thing left to decide. When Manurva chose October 22nd for several reasons.

First, it was the night of the new moon, meaning maximum darkness for her approach. Second, Master Blackwood had invited guests for dinner and drinks. The men she hated most would be gathered in one place. Third, the cotton harvest was nearly complete, meaning field slaves would be exhausted and less likely to intervene or investigate unusual sounds.

Andfourth, October 22nd was exactly 8 months after they took patients, a symbolic number in the old traditions. The invited guests were Dr. Ambrose Whitfield, overseer Silus Crowe, a neighboring planter named Thirsten Caldwell, who had purchased two of Manurva’s friends and worked them to death within a year, a slave trader named Marcus Grimshaw, who specialized in separating families, and Josiah, the driver, who had betrayed his own people for scraps from the master’s table, plus Cornelius Blackwood himself.

Six men, six cats, perfect symmetry. Eleanor Blackwood was scheduled to be away, visiting her sister in Milligville. This was intentional on Manurva’s part. She had listened to conversations, learned the schedule, and chose this specific date because Elellanor would be absent. Not because Manurva wanted to spare her, but because Elellanena would get her own special punishment later.

Tonight was about the men who had directly harmed patients and countless others. On the morning of October 22nd, Manurva woke before dawn and performed the ritual her mother had taught her. She bathed in the creek, washing away the civilized smell of soap and replacing it with natural scents, crushed pine needles, river mud, wild herbs that would help her blend into the forest signature.

She fasted throughout the day, keeping her mind clear and sharp. She worked the fields mechanically, conserving her energy, visualizing every step of the night to come. As sunset approached, she felt remarkably calm. There was no fear, no doubt, no hesitation. She had transformed completely into the thing she was meant to be, an instrument of justice that slavery had tried but failed to break.

If you’re wondering whether this was madness or righteousness, consider what it means to live in a world where the law protects your rapist, where the state sells your children, where the church blesses your chains. In such a world, what is sanity? What is justice? At 7:00 that evening, the guests began arriving at the big house.

Manurva watched from the vegetable garden, memorizing positions, counting heads, noting details. Blackwood greeted them on the porch with bourbon and cigars. They laughed loudly, voices carrying across the plantation. Inside the dining table was set for six. Cook had prepared roast venison, cornbread, collarded greens, sweet potato pie.

The masters would eat like kings while the slaves survived on cornmeal mush. At 8:00, Manurva reported to the overseer’s cabin as required, showing him the day’s trapped game, three rabbits and a possum. Silas dismissed her with a grunt, already drinking, eager to join the party at the big house.

She walked back toward the quarters, waited until full darkness at 8:30, then melted into the forest. The walk to the cages took 35 minutes. Manurva moved through the woods like a shadow, avoiding paths, navigating by memory and instinct. The forest was alive with night sounds, crickets, frogs, the distant hoot of an owl. She added her own sound to the chorus, a low humming that announced her presence to the cats.

When she reached the cages, all six were awake and alert, sensing something different about tonight. The lead panther paced his cage, restless energy coiled and ready. The mated pair pressed against their cage bars, watching Manurva with luminous eyes. The young cougars wrestled playfully, innocent killers waiting for direction, and the link sat perfectly still, patient as death itself.

Manurva moved between the cages, speaking to each cat in the old language, preparing them for what came next. She anointed herself with scents she had collected. Blackwood’s cologne dabbed on a cloth and pressed to her wrist. Silus Crow’s tobacco stained bandana wrapped around her left arm. Dr. Whitfield’s medicine bag sent on her right shoulder.

She was marking herself as safe as separate from the targets. The cats sniffed these scents and understood attack everything except this scent profile. At 9:15, she heard distant laughter from the direction of the big house. The dinner party was in full swing. It was time. She opened the first cage. The lead panther emerged in one fluid motion, 140 lb of pure muscle and predatory intent.

He rubbed against Manurva’s legs once, marking her, then sat and waited. She opened the second and third cages, releasing the mated pair. They flanked the male. Three panthers moving in unconscious coordination. Then the cougars, then the lyns. Six deadly cats surrounded Manurva in a circle, awaiting her command.

She raised her face to the night sky and sang. It was not a human sound, not quite. It was the calling song her mother had taught her. The sound that meant, “Follow me. We hunt together. Death comes to those who wronged us.” The cats responded with their own vocalizations. low growls that rumbled like distant thunder. Then Manurva Hall, the panther queen, led her army toward the big house.

They moved through the forest like ghosts. Manurvaat the center, cats surrounding her in a loose formation, silent except for the occasional snap of twig under heavy paw. The distance from cages to big house was 3/4 of a mile through woodland, then across open ground for the final 200 yd. This was the dangerous part.

If anyone saw them approaching, the plan would collapse. But it was after 9:00 on a moonless night. The field slaves were locked in their quarters, exhausted from 14-hour work days. The house slaves had finished serving dinner and retreated to the kitchen. The only people awake and alert were the six men in Blackwood’s study, drinking bourbon and laughing about the price of cotton and the quality of their human property.

Manurva reached the edge of the forest at 9:40. From here she could see the big house clearly, windows blazing with lamplight, shapes moving behind curtains. She could hear their voices, could smell cigar smoke on the wind. The cats pressed close to her, sensing proximity to targets, muscles twitching with anticipation.

She needed to get them closer before releasing them. Panthers and cougars could sprint incredibly fast over short distances, but they tired quickly. She wanted them to reach the house with maximum energy, so she did something insane and brilliant. She walked straight toward the big house, cats following close, keeping to the shadows of the magnolia trees that lined the approach.

Anyone glancing out a window would see a slave woman walking toward the house. Nothing unusual. They would not see the six predators moving in perfect synchronization behind her, shadows within shadows. She reached the house, pressed against the side wall. The study window was 10 ft to her right, slightly open to let in cool night air.

She could hear everything. Blackwood’s voice, gentlemen, a toast to cotton to profit and to the peculiar institution that makes it all possible. Glass clinking, laughter. Dr. Whitfield, speaking of the peculiar institution, Cornelius, have you heard about the new medical theories regarding negro pain tolerance? Fascinating research.

More laughter. Manurva’s hands clenched into fists. Silus crow. Hell, I can tell you about pain tolerance. Gave one buck 200 lashes last month and he was back in the fields next day. They’re built different. That’s for damn sure. Thirsten Caldwell. 200. That’s excessive even for seasoning. I prefer breaking them psychologically.

Separate families threaten children. Far more effective than the whip. Marcus Grimshaw, the slave trader. That’s why I do good business, gentlemen. Families are worth more broken up than kept together. Sold that pregnant girl to Madame Dupra’s establishment in Savannah 8 months back, made a tidy profit. Manurva went completely still.

They were talking about patience, laughing about it. Josiah’s voice, eager to impress. That girl’s mama still works the fields. Manurva broke her good when you sold that child, Master Blackwood. Ain’t heard a peep of complaint from her since? More laughter. Blackwood. Sometimes harsh measures are necessary. Can’t have them thinking they have rights over their offspring.

That was the moment Manurva’s last shred of humanity evaporated. She turned to the six cats crouched behind her and whispered three words in the old tongue, words that meant, “Kill them all. Then she smashed the study window with a rock. The sound of shattering glass was immediately followed by six streaks of fur and fury exploding through the broken window into Cornelius Blackwood’s study.

What happened next lasted approximately 4 minutes and 17 seconds. Though it must have felt like hours to the men inside, and those four minutes rewrote everything, the white men of Burke County, Georgia, thought they knew about control, power, and the natural order. The lead panther hit Dr. Whitfield first. The old man was standing nearest the window, cigar in hand, when 140 lbs of black muscle crashed into his chest.

He went down hard, the back of his skull cracking against the hardwood floor. Before he could scream, the panther’s jaws closed around his throat and ripped sideways with savage efficiency. Blood sprayed across the oriental rug in arterial spurts. Whitfield’s hands clutched uselessly at the massive head, fingers tangling in black fur, then going limp as consciousness fled.

The panther held on for another 10 seconds, ensuring death, then released and spun toward the next target. Silus Crow had the fastest reflexes. Years of brutality had honed his instincts for violence. He grabbed a fire poker from the hearth and swung it like a club at the mated panther pair coming through the window.

The female took the blow across her shoulder, but barely slowed. She twisted mid lunge and latched onto Crow’s right forearm, fangs puncturing through muscle and scraping bone. Crow screamed, a high-pitched sound of pure animal terror that had never crossed his lips before. He’d inflicted that sound on countless slaves. Now he knew what it tasted like.

The male panther circled behind Crow and sprang, hitting him between the shoulder blades. 260 lb of combined catweight drove Crow face first into the floor. The male’s claws sank into the overseer’s back, shredding through his shirt and flesh, scoring deep furrows down his spine. Crow tried to crawl away, one arm useless, the other clawing at the floor.

The female released his arm and repositioned, jaws closing on the back of his neck. One savage shake and his cervical spine separated with an audible crack. He stopped moving. The three young cougars went for Thirst and Caldwell. The neighboring planter had frozen in his chair, bourbon glass slipping from nerveless fingers, his mind unable to process what his eyes were seeing.

The cougars hit him in a coordinated rush, one taking his left thigh, one his right shoulder, one his face. He finally found his voice and screamed as fangs tore into flesh from three directions simultaneously. The cats dragged him from the chair and onto the floor where they worked with the terrifying efficiency of pack hunters. The one on his thigh bit down and thrashed, severing the femoral artery.

Blood pumped across the floor in rhythmic gouts. Caldwell’s screams turned to gurgles as the cougar on his face bit through his jaw and into his throat. 37 seconds from first contact to final breath, Marcus Grimshaw, the slave trader, showed his true nature. He abandoned his companions instantly and bolted for the door. He almost made it.

His hand was on the doornob when the lynx hit him from behind with precision that would have been beautiful if it weren’t so lethal. The lynx was smaller than the big cats, only 40 lb, but pound-for-pound the deadliest predator in North America. He latched onto Grimshaw’s lower back with claws that sank 3 in deep, then climbed the man’s body like a tree, shredding flesh and muscle with each movement.

Grimshaw spun wildly, trying to dislodge the cat, slamming his back against the door. The Lynx held on and sank its teeth into the base of Grimshaw’s skull, right where the spine met the brain stem. The Lynx’s powerful jaws crushed vertebrae. Grimshaw dropped like a puppet with cutstrings, dead before he hit the floor.

The lynx released and sat on the corpse, calmly licking blood from its paws. Josiah the driver tried to hide, he dove under Blackwood’s massive oak desk, curling into a ball, whimpering prayers to a god that had never protected black people from white violence, and certainly wasn’t going to protect a traitor from justice. One of the young cougars stalked toward the desk, moving with the deliberate pace of a cat who knows its prey is cornered.

The cougar sat in front of the desk for a moment, tail swishing, savoring the fearscent pouring off the man inside. Then it crouched, bunched its muscles, and sprang onto the desktop with a single fluid leap. It looked down at Josiah through the gap between desk and floor. “Please,” Josiah whispered. Please, I’m one of you.

I’m enslaved, too. Please. The cougar did not care about alliances or explanations. It had been trained to attack a specific scent profile, and Josiah wore that scent. The cat reached under the desk with one massive paw and hooked its claws into Josiah’s shoulder, dragging him out into the open like a fish pulled from water.

Josiah tried to fight, hammering his fists against the cougar’s head. The cat barely noticed. It positioned itself over his chest, looked directly into his eyes, and then bit down on his face. The sound of breaking bones was distinct. When the cougar raised its head, Josiah’s features were no longer recognizable.

That left Cornelius Blackwood, the master of Willowre Plantation, the man who thought himself civilized and sophisticated, the Yale graduate who quoted Greek philosophy while raping 14-year-old girls, the man who had sold Manurva’s daughter to a brothel for $800. He stood pressed against the far wall of his study, surrounded by dying and dead men, six predators slowly turning their attention toward him. Blood covered everything.

The expensive Persian rug was soaked crimson. The oak paneling was splattered with arterial spray. The portrait of Blackwood’s grandfather, who had founded the plantation, watched the carnage with painted eyes that would never blink again. The room smelled like a slaughter house.

Copper blood released bowels, fear, sweat. Blackwood tried to speak, his mouth opened and closed, but no sound emerged, his bladder released, urine darkening his expensive trousers, adding a sharp ammonia tang to the air. He had spent 47 years secure in his position as master, never once questioning his right to own other humans, never once doubting his safety.

Now he understood with absolute clarity that all of it had been illusion. The cats did not rush him. They formed a semicircle, cutting off any escape route and sat. They were not mindless killing machines. They were intelligent hunters, and they had been trained for thisspecific moment.

They sat and waited because their alpha had not yet given the final command. That’s when Manurva climbed through the broken window. She moved with eerie grace, stepping over Dr. Whitfield’s corpse without looking down, her bare feet leaving bloody footprints on the white oak floor. The cats acknowledged her presence with low rumbling purr, but did not break formation.

Manurva walked through the semicircle of predators until she stood directly in front of Cornelius Blackwood. They looked at each other, master and slave, rapist and mother of his victim, human and woman turned weapon. “Do you remember my daughter’s name?” Manurva asked in perfect English, her voice absolutely calm. Blackwood’s mouth worked.

“Patience,” he finally whispered. “Do you remember what you did to her?” Blackwood swallowed hard. His eyes darted toward the cats, the bodies, the blood. I I didn’t. She was just She was 14 years old, Manurva interrupted. She was my baby and you raped her. Then you sold her to a wh house where she is being raped every night by men who pay for the privilege.

She was carrying your child when you did that. Do you remember? Tears streamed down Blackwood’s face. I’m sorry. God help me. I’m sorry. Please, I’ll free you. I’ll free everyone. I’ll sign the papers right now. Please don’t do this. Manurva tilted her head slightly, considering for a moment something almost like mercy flickered in her eyes.

Then it died. You don’t get to buy your way out this time, she said softly. You don’t get to negotiate. You don’t get to own this moment. This is mine, and this is for patience. She took one step back and sang the killing note. A sound that started low in her chest and rose to a frequency that made the window panes vibrate.

It was the sound a mother leopard makes when teaching her cubs to hunt. The sound that means this is prey. Take it. Devour it. Leave nothing. The six cats exploded forward simultaneously. Cornelius Blackwood screamed as panthers, cougars, and lyns converged on him in a wave of fur and fangs and claws.

He disappeared beneath their mass, his screams cutting off abruptly as a panther’s jaws closed on his throat. The cats worried at his body like dogs with a bone. Each one taking their piece, tearing and ripping and shredding until there was nothing left that resembled a man. Manurva watched it all with eyes that held no pity, no regret, no horror.

She watched until the sound stopped, until the only movement was the cat’s sides heaving with exertion, until the silence filled the room like a presence. Then she sang again, a different note, one that meant, “Enough. Come to me. We are finished.” The cats immediately disengaged from their kills and returned to her side, rubbing against her legs, purring, marking her with blood and scent.

She touched each one, murmuring words in the old language, honoring them for their service. The entire massacre had taken 4 minutes and 17 seconds from broken window to final death. Six men dead. Not one of them died quickly or cleanly. Justice had been served in the most primal form possible. Predator destroying predator.

The natural order reasserting itself in a world that had tried to declare one group of humans less than beasts. Manurva stood in the center of the carnage and felt nothing but cold satisfaction. This was not enough. It would never be enough. No amount of blood could bring patience back, could undo 22 years of slavery, could restore the three children she’d lost, could return her to the life she should have lived as a free woman in her mother’s village. But it was something.

It was agency. It was choice. It was power. For the first time in 22 years, Manurva Hall had decided something for herself and watched it become reality. She heard sounds outside, shouting, running feet. The screams had been heard despite the thick walls. People were coming. The illusion of time standing still shattered, and Manurva understood she had perhaps 5 minutes before the plantation erupted in chaos.

She moved quickly, checking each body to ensure death. She retrieved items from Blackwood’s desk, the ledger where he recorded punishments, the papers showing patients’s sale, documents of ownership for 143 humans. She stuffed these into a satchel. Then she opened Blackwood’s safe, which she’d watched him access countless times while cleaning his study.

Inside was $2,300 in cash, gold coins, and ownership papers for the plantation itself. She took it all. Finally, she looked at the six cats. They were tired now, bellies full of human flesh, adrenaline wearing off. She could not take them with her where she was going, but she could set them free. Go, she said in English and the old tongue, return to the forest, hunt prey.

Remember that once you were instruments of justice, remember that once you brought down giants. The cats looked at her with luminous eyes, understanding on some level deeper than language. One by one they leapedback through the broken window and disappeared into the night. Within seconds they were gone, melting into the Georgia wilderness that had spawned them.

Manurva was alone in a room full of corpses. She heard the front door burst open downstairs, heard voices shouting for Master Blackwood, heard feet pounding up the stairs. She had perhaps 30 seconds before they reached the study. She walked to the window, looked out at the night sky where stars blazed with cold indifference. She thought of patience somewhere in Savannah enduring horrors Manurva could not stop.

She thought of Joseph sold to Louisiana, of Grace and Samuel, dead from neglect and brutality. She thought of her mother cut down defending a sacred grove. She thought of everyone she had been and everything slavery had tried to take from her. They could take her body. They could take her life, but they could never take this moment, this night, this perfect act of resistance.

The door to the study flew open. Three white men from a neighboring plantation burst in. Drawn by the screams, they froze, jaws dropping, unable to process the scene before them. Blood everywhere, body parts scattered, and standing calmly by the window, a black woman holding a satchel, looking directly at them with eyes that held no fear whatsoever.

“What? What have you done?” one of them whispered. Manurva smiled. It was not a pleasant smile. It was the smile of someone who had shattered the world and found that the pieces looked better broken. Justice, she said simply. Then she jumped through the window. She hit the ground 12 ft below, rolled to absorb the impact, and sprinted for the forest.

Behind her, shouting exploded as men poured out of the big house. Within minutes, someone would think to ring the bell, to raise the alarm, to organize a search party. But Manurva had those critical minutes of chaos, and she used them well. She ran through the forest like a woman possessed. Not the forest she’d entered as a broken slave, but forest she now knew intimately after eight months of nightly journeys.

She knew every path, every hiding spot, every water source. The men chasing her would have dogs, guns, torches, but she had knowledge, darkness, and nothing left to lose. She ran for 2 hours, putting distance between herself and Willowmir. When she reached the Savannah River, she did not hesitate.

She dove into the cold water, swimming across the width of the river, letting the current carry her downstream before emerging on the far bank. This would break her scent trail, confuse the dogs. On the other side, she oriented herself by the North Star, and headed toward Augusta, not to enter the city, which would be suicide, but to skirt around it and continue north.

She had $2,300 in cash, papers showing patients’s sale, and intimate knowledge of Savannah’s red light district. She would find her daughter. She would free her. And then they would run together toward whatever freedom meant in a country that made bondage legal. But first she had one more stop to make.

Because Elellanena Blackwood was still alive, visiting her sister in Milligville, completely unaware that she was now a widow, and Manurva’s justice was not complete. That story, however, would take place 3 days later when Eleanor returned to find her husband dead and her house servant missing. When she discovered what Manurva had done, she would faint from horror.

And when she woke, she would find Manurva standing over her bed with a knife, ready to finish what the cats had started. But for now, as dawn broke over Georgia on October 23rd, Manurva Hall was free. Truly free for the first time in 22 years. She walked north through the forest, following stars and instinct, while behind her, the plantation world she’d shattered tried desperately to make sense of a massacre that would haunt their nightmares for generations.

The immediate aftermath was chaos. When the sun rose on October 23rd, Willamir Plantation looked like a battlefield. The sheriff arrived from Augusta with 20 armed men. They found six bodies in the study, torn apart with such savagery that identification required personal effects. The scene defied all logic. What animal could have done this? Why were there no tracks except bloody paw prints that led to the window and disappeared? Where was the enslaved woman everyone agreed must be responsible? The sheriff examined the carnage carefully. He’d seen violence

before, bar fights, stabbings, even a murder or two, but nothing like this. The bodies showed signs of being attacked by multiple large predators. But how did wild cats enter a locked room, kill six men, and leave without being shot or subdued? It was impossible. Unless, someone whispered, the cats had been controlled, directed, weaponized by someone with unnatural knowledge, a conjure woman, maybe.

the older slaves would know about such things. The sheriff dismissed this as superstitious nonsense. But the seed of fear had been planted because if anenslaved woman could do this, what did that mean about the natural order white people had constructed? What did it mean about who truly held power? They found Manurva’s pallet in the quarters empty, her few possessions gone.

They discovered the cages in the forest three days later after a massive manhunt. The cages were empty but showed signs of long occupation. Cat hair, scratch marks, blood. The construction was sophisticated, showing intelligence and planning. The implications were terrifying. Word spread through Burke County like wildfire.

An enslaved woman had trained wild cats to murder her master and five other white men. She had escaped and was somewhere in the wilderness, possibly still controlling killer animals. Panic seized the region. Plantation owners slept with loaded rifles. Some sold their slaves immediately, no longer trusting anyone black.

Others implemented draconian new controls, multiple locks on quarters, armed guards at night, inspection of slave movements. The governor of Georgia offered a reward, $1,000 for Manurva Hall, dead or alive. Wanted posters went up across the state, though they had only rough descriptions. Black woman, 30s, average height, answers to name Manurva. It was useless.

Thousands of enslaved women matched that description. Meanwhile, the slave population of Burke County experienced a strange transformation. They did not speak openly, could never speak openly. But among themselves in whispered conversations after dark, Manurva became something more than human. She became legend. She became hope.

If one woman could strike back so completely, so devastatingly, what else was possible? The story grew with each telling. Some versions had her controlling 20 wild cats. Some said she turned into a panther herself. Some claimed she was invulnerable to bullets blessed by African gods. The truth was simultaneously more mundane and more remarkable.

Manurva Hall, now calling herself Em again, made it to Savannah 3 days after the massacre. She used $50 of the stolen money to purchase a forged freedom pass from a black barber who ran a discrete side business. The pass declared her a free woman of color, legally manumitted, traveling to Charleston on business. It would not hold up under serious scrutiny, but it would allow her to move through Savannah without being immediately seized.

She found the brothel where patients had been sold. Madame Dupra’s establishment occupied a threestory building near the docks, painted gaudy red, music and laughter spilling from open windows, even in daylight. Manurva watched the place for a full day, learning the rhythms, identifying the guards, mapping exits.

That night, she entered through a kitchen window and moved through the building like a ghost. She found patients in a thirdf flooror room, chained to a bed, barely conscious from lordinum they used to keep the girls compliant. Patience had lost weight. Her eyes were hollow, and she stared at the ceiling without seeing. Patience,” Manurva whispered, touching her daughter’s face. “Baby, it’s Mama.

I’m here.” Patience’s eyes focused slowly. Then, impossibly, she smiled. “Mama, are you real?” “I’m real, and we’re leaving.” Manurva picked the lock on the chains, a skill she’d learned from an enslaved blacksmith years ago. She wrapped patients in a stolen coat, gave her shoes, helped her to the window where a rope waited.

They climbed down to the alley, moved through Savannah’s dark streets, and were on a northbound boat by dawn, hidden in the cargo hold with help from a free black sailor who asked no questions. They traveled for 3 months, always moving, always careful. They went up the coast to Charleston, then to Wilmington, then to Norfolk. In each city, Manurva used stolen money to buy forged papers to pay for passage to secure temporary shelter.

Patients slowly recovered, though the trauma ran deep. The baby she’d been carrying had been lost to miscarriage within days of arriving at the brothel. They finally reached Philadelphia in January of 1858. The city had a large free black population and active abolitionist networks. Manurva made contact with the Underground Railroad through a Quaker church.

She shared her story, not all of it, but enough. Within weeks, both women had new identities, jobs, and a small room in a boarding house run by free black families. Manurva never trained cats again. She worked as a seamstress, attended church, lived quietly, but she kept the satchel with Blackwood’s papers, kept the newspapers that covered the Willowre massacre, kept the wanted poster with her name.

These were proof that she had struck back, that she had refused to accept powerlessness, that she had weaponized nature itself against her oppressors. patients eventually married, had children, lived to see the end of slavery in 1865. She named her first daughter Manurva and her second daughter Am, keeping the memory of both identities alive.

She told her children the real story, notthe legend, so they would know their grandmother’s strength and courage. Manurva lived to age 73, dying peacefully in her sleep in 1892, 27 years after emancipation. She was buried in a black cemetery in Philadelphia under her African name, the name her mother had given her, the name that meant peace.

Her gravestone was simple, Imim. She made peace through justice. But back in Georgia, the legend of the panther queen lived on. The story passed through generations of enslaved people, then freed people, then their descendants. With each telling, new details emerged, some true, some embellished. Some versions said Manurva returned to Georgia during the Civil War and fought alongside Union troops.

Her six Wildcats attacking Confederate soldiers. Some said she became an abolitionist speaker in the North, though she never publicly identified herself. Some said she freed dozens of other slaves using her mysterious connection to wild animals. The white population of Burke County tried desperately to suppress the story.

They burned records, intimidated witnesses, threatened anyone who spoke of it, but they could not erase what had happened. The Willowre Massacre remained the most spectacular act of slave resistance in Georgia history. A brutal reminder that oppression always contained within it the seeds of its own destruction.

Modern historians have attempted to separate fact from fiction regarding Manurva Hall. Court records confirm the deaths of six men at Willamir Plantation on October 22nd, 1857. Sheriff reports mention animal attacks, but offer no explanation for how wild cats entered the house or were directed. The plantation was sold at auction in 1858 after Elellanena Blackwood died under mysterious circumstances.

Found dead in her bed with her throat cut. Officially recorded as a robbery gone wrong, though nothing was stolen, Manurva’s flight and survival in Philadelphia are documented through church records, property leases, and census data. The papers she carried, Blackwood’s ownership documents, Patients’s bill of sale, the massacre newspaper coverage were donated to the Smithsonian in 1947 by Patients’s granddaughter, making them available for historical research.

As for the wild cats, hunters reported unusual sightings for years after 1857. Multiple reports described panthers and cougars that showed no fear of humans that seem to hunt cooperatively in ways not normally observed in wild cats that bore scars suggesting prior contact with people.

Whether these were the same six cats Manurva trained or different animals or exaggerations built on fear, no one could say with certainty. What remains certain is this. Manurva Hall refused the role slavery tried to force upon her. When the law offered no protection for her daughter, when the church blessed her chains, when the state defended her rapist, she created her own justice using knowledge passed down through generations of African women who understood that power is not given but taken.

She proved that even the most brutal system of oppression cannot fully control the human spirit’s capacity for resistance. If you’re wrestling with the morality of what Manurva did, that wrestling is appropriate. She killed six men with calculated brutality, using animals as weapons, planning for months, showing no mercy.

By any legal definition, she was a murderer. But what is the appropriate response to a system that legally sanctions rape, family separation, torture, and murder? When the law itself is immoral, when justice is unavailable through legitimate channels, what does resistance look like? These are questions Americans still grapple with today.

The legacy of slavery did not end with emancipation. It continued through Jim Crow, through lynching, through segregation, through mass incarceration, through systemic inequality that persists in housing, education, employment, and justice. The chains are different now. But the spirit that animated Manurva, the refusal to accept powerlessness, the insistence on dignity, the willingness to risk everything for freedom remains relevant.

Manurva’s story was suppressed for decades because it was too dangerous. It showed enslaved people as intelligent, strategic, capable of complex planning and execution. It showed them weaponizing their knowledge against oppressors. It showed them winning even temporarily. Such narratives undermined the entire ideology of white supremacy, which required black people to be seen as passive, childlike, incapable of sophisticated thought or action.

But Manurva existed. Her story is real, and it is one of thousands of resistance narratives that American history textbooks have chosen to ignore. Every time we tell these stories, we push back against the comfortable lie that slavery was somehow benign that enslaved people accepted their condition, that resistance was rare or futile.

Every time we remember the panther queen of Georgia, we honor everyone who refused to be broken. Thefinal chapter of Manurva’s story belongs not to her, but to those who came after. Her great great grandchildren participated in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Her great great grandson is currently a civil rights attorney in Atlanta.

The blood that flowed through the Panther Queen flows through living people today. People who inherited not just her DNA, but her refusal to accept injustice. In 2012, a group of black activists and historians erected an unofficial memorial near the site of the former Willowir plantation. The plantation itself is long gone, plowed under for commercial development.

But the memorial stands in a small park, a simple stone marker with a carved image of a panther and the words for Manurva Hall and all those who resisted. Your courage was not in vain. That memorial has been vandalized three times. Each time it has been repaired and rebuilt by community members who understand why the story matters.

Because Manurva’s act of vengeance, while extreme, represents a fundamental truth about human nature. We are not meant to be owned. We will resist oppression by any means necessary. And sometimes resistance looks like violence because violence is what oppression understands. The story of the panther queen reminds us that history is not just what happened to people, but what people did in response to what happened to them.

Manurva Hall was not a passive victim of slavery. She was an active agent in her own liberation and the protection of her daughter. She used intelligence, ancestral knowledge, extraordinary patience, and yes, brutal violence to strike back at a system designed to destroy her humanity, was it justice or murder? That question has no simple answer.

But ask yourself this, in a world where the rape of a 14-year-old girl is legal, where selling pregnant teenagers to brothel is protected by law, where black mothers have no rights to their own children? What does justice even mean? When every legitimate avenue of protection is closed, when the law itself is your oppressor, how should one respond? Manurva answered that question in the most primal way possible.

She became predator instead of prey. She armed herself with the wildest things nature had to offer and turned them loose on the men who had stolen everything from her. And for one night on October 22nd, 1857 in Burke County, Georgia, the natural order was inverted. The slave became master and six men learned what it felt like to be powerless before a force they could not control.

That lesson echoed through the South for years. That’s why slaveholders tried so hard to suppress the story. Because if one woman could do this, what was to stop others? If animals would obey an enslaved woman before obeying masters, what did that say about the supposed natural hierarchy? The panther queen was dangerous, not because of the six men she killed, but because of the idea she represented. Resistance is possible.

Power can be seized and no oppression is absolute. Remember Manurva Hall. Remember that she existed. Remember that she fought back. Remember that she won at least for one night. Remember that her daughter survived. Remember that her descendants live today. Remember that the spirit that drove her, the insistence on dignity, on agency, on freedom, cannot be killed, no matter how much violence is used to suppress it.

This is not a comfortable story. It was not meant to be. Comfortable stories do not change the world. Manurva’s story should disturb you, challenge you, make you question assumptions about violence, justice, and resistance. It should make you wonder what you would do in her position.

Whether you would have the courage to risk everything, whether you would choose life in chains or death fighting for freedom. If you found this story powerful, share it. Tell others about the Panther Queen. push back against the sanitized version of American history that erases stories like hers. Demand that schools teach the full truth of slavery, including the violence of the system and the violence of resistance to that system.

Support organizations working to address the legacy of slavery through education, reparations, and systemic change. And most importantly, when you see injustice today in policing, in courts, in economics, in any system that treats humans as less than human, remember that silence is complicity. You don’t need to train wild cats or commit violence.

But you do need to resist. You do need to speak up. You do need to fight in whatever way your conscience and circumstances allow. The story of Manurva Hall is not just history. It is a mirror held up to the present asking us what would we be willing to risk for justice. What would we sacrifice to protect those we love? When would we say enough and mean it absolutely? These questions do not have easy answers, but they are the questions that matter.

Remember the panther queen. Remember that she was real. Remember that she struck back. Remember that she survived.Remember that her story continues in the living descendants who carry her blood and her spirit. Remember that oppression has never defeated the human spirit permanently and that resistance in all its forms, including its most violent forms, has always been part of the struggle for freedom.

This is how we honor those who fought before us. By remembering truthfully, by telling their stories completely, and by continuing their fight in our own time. The chains look different now, but the fight remains the same. May we all have even a fraction of Manurva’s courage when we are called to stand against injustice.

May we all be worthy of the sacrifices made by those who came before. The panther queen of Georgia lived. She resisted. She struck back and she won. Her story ends here. But the legacy of resistance she represents continues in every person who refuses to accept oppression. In every voice that speaks truth to power, in every act that insists on human dignity against a system designed to destroy it.

Remember Manurva Hall. Tell her story and never ever forget that freedom has always been won by those brave enough to fight for it, no matter the cost.