On the morning of October 9th, 1856, beneath the rot iron balconies of the Montgomery Cotton Exchange, a woman was sold for the equivalent of $412,000 in today’s currency. The auctioneers’s hammer struck 23 times before silence finally claimed the crowd. And when the sale concluded, the winning bidder vomited into a brass patoon before signing the bill of sale with trembling hands.

No newspaper reported the transaction. No ledger survived to explain it, and the woman herself never spoke a single word throughout the entire proceeding. Standing on that auction block with her eyes fixed on something no one else could see, wearing an expression that witnesses would later describe as a smile that wasn’t quite a smile.

More like someone watching a trap spring shut exactly when they knew it would. The price shattered every record in Alabama’s history of human commerce. It exceeded the combined value of three working plantations. It represented more wealth than most men in that room would accumulate across their entire lifetimes. And yet, six different buyers competed for her with a desperation that bordered on madness, driving the price upward in increments that made no economic sense, following no logic except the terrible certainty that whoever possessed this woman would possess something worth infinitely more than money.

What secret could justify such an impossible sum? What knowledge could transform a human being into the most expensive piece of property ever sold south of the Mason Dixon line? And why did three of the men who bid on her that October morning die under mysterious circumstances within 18 months while two others fled Alabama forever, abandoning their plantations, their families, their entire lives as though pursued by something more terrifying than debt or scandal.

Now, let us return to that October morning when something walked onto the Montgomery auction block that should never have been there at all. Montgomery in 1856 was a city drunk on cotton money and convinced of its own invincibility. The Alabama River carried paddle wheelers loaded with bales destined for textile mills in Manchester and Boston.

And the elegant homes along Dexter Avenue housed families whose wealth had been extracted from Delta soil by the labor of people they legally owned but never truly controlled. The city’s 28,000 residents divided themselves into the usual categories: white and black, free and enslaved, powerful and powerless.

Though these divisions were always more fragile than anyone wanted to admit, the Cotton Exchange stood on Commerce Street, a Greek revival building with columns that aspired to ancient dignity, but mostly succeeded in looking like a theater set for a play about empire. Inside the auction floor could accommodate 200 men comfortably, and on busy days it did, with planters and speculators and merchant brokers conducting the transactions that kept Alabama’s economy functioning.

Human beings changed hands here 3 days a week, sold alongside cotton futures and warehouse space and shares in riverboat companies. Everything negotiable, everything with a price. everything reduced to numbers in leatherbound ledgers that recorded profit and loss without ever acknowledging the moral bankruptcy that made such records possible.

The auctioneer that October morning was a man named Silas Whitmore, 51 years old, with a voice like gravel and a reputation for ruthless efficiency. He had conducted more than 8,000 sales during his career, and he took professional pride in his ability to read a crowd, to sense when biders were reaching their limit, to extract maximum value from every transaction.

His commission depended on final prices, and he had developed techniques for manufacturing competition, even when natural demand seemed insufficient. A well-timed pause, a strategic question directed at a reluctant bidder, a casual mention of another buyer’s interest. These were the tools of his trade, and he wielded them with the skill of a surgeon.

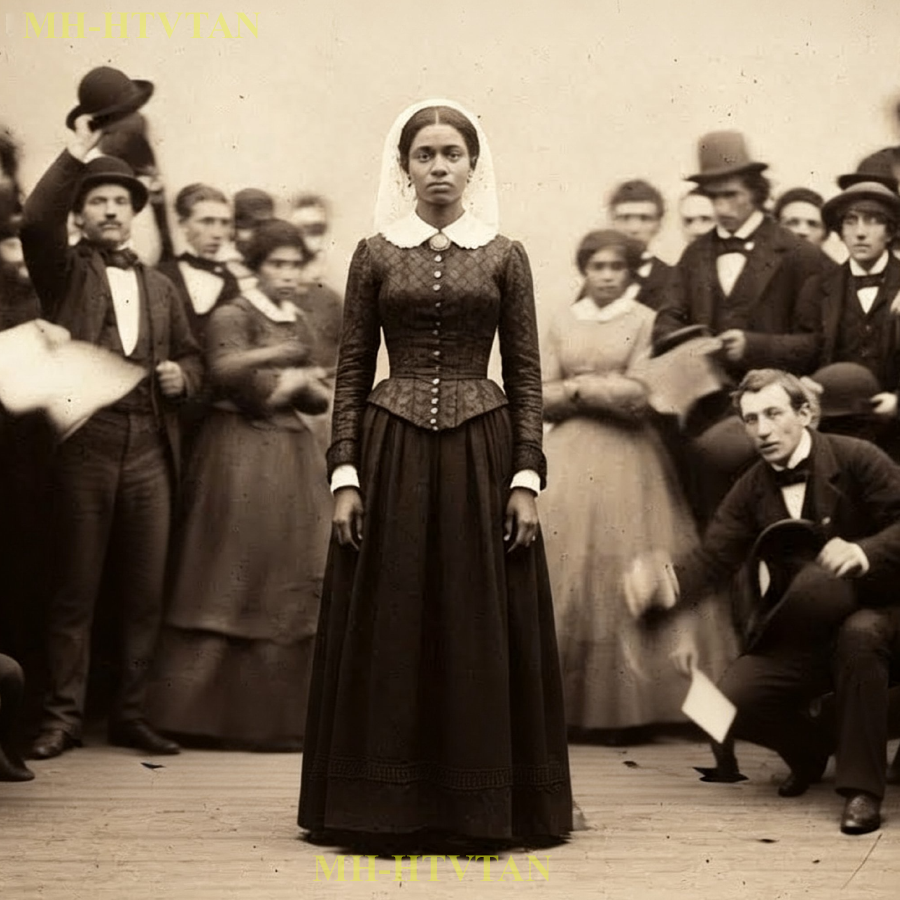

The morning had proceeded normally until approximately 10:30, when the side entrance opened, and three men entered, escorting a woman whose presence immediately altered something fundamental about the room’s atmosphere. The crowd’s conversation didn’t stop exactly, but it changed quality, becoming quieter, more cautious, as though everyone sensed simultaneously that something unusual was about to occur.

She appeared to be somewhere between 30 and 40 years old, though her face possessed a quality that made precise age determination difficult. Her skin was the color of Creek Water Coffee, and her features suggested mixed ancestry that might have included African, European, and possibly Creek or Cherokee bloodlines. She stood approximately 5’7 in tall, unusually tall for a woman of any race in that era, and her posture radiated a composure that seemed almost offensive given her circumstances.

She wore a plain gray dress, clean but showing wear, and her hair had been pulled back in a style that revealed a face of disturbing intelligence. But it was her hands that caused the first murmurss of confusion. They were covered in ink stains, the kind that accumulate on fingers that spend hours writing, and her palms bore calluses in locations consistent with pen work rather than field labor or domestic service.

For anyone knowledgeable about enslaved labor, these hands told an impossible story. Enslaved people were forbidden by law from learning to read or write in Alabama. And while some owners violated this statute secretly, they certainly never allowed their property to develop the kind of extensive writing calluses this woman displayed.

Silus Whitmore descended from his platform, his professional mask slipping momentarily to reveal genuine uncertainty. He spoke briefly with the three escorts, examining documents they produced, and those nearest the front would later report that his face went through a series of expressions suggesting confusion, then disbelief, then something approaching fear.

When he returned to his platform, he held a sealed envelope in his left hand, and his right hand trembled slightly as he raised it to call for attention. The auction floor fell silent with unusual speed. Men sensed that something extraordinary was about to happen, and even the most jaded speculators leaned forward, their commercial instincts detecting an opportunity they couldn’t yet define.

“Gentlemen,” Whitmore began, his voice lacking its usual confidence. We have before us today a lot that requires special introduction. The woman you see has been designated property number 47. No name provided. Age estimated at 35 years. No documented history of fieldwork, house service, or any conventional skilled trade. A voice called out from the middle of the crowd.

Then what’s she worth? Whitmore. Why waste our morning? Whitmore’s jaw tightened. The opening bid has been established at $8,000. The silence that followed was absolute. $8,000 exceeded what most skilled craftsmen, white or black, free or enslaved, could earn in a decade. It represented the price of a complete blacksmith operation or two experienced carriage drivers or enough field hands to work a 100 acres of cotton clears throat.

For a single woman with no documented skills, the figure was insane. But Silas Whitmore didn’t lower the price. Instead, he did something none of the veteran auctiongoers present had ever witnessed. He broke the seal on the envelope he carried and began reading aloud, his voice growing quieter with each sentence, as though he hoped that speaking softly might somehow lessen the impact of what he was revealing.

The seller provides the following sworn statement executed before Judge Harrison Mitchell of Montgomery County on October 4th of this year. The property designated number 47 possesses knowledge of significant value to parties concerned with financial transactions, property ownership, and matters of personal reputation.

Said knowledge has been verified through demonstration to five witnesses whose identities must remain confidential for their own protection. The purchaser will receive along with standard documentation of sale a private letter explaining the nature and extent of this knowledge along with recommendations for its proper utilization.

The crowd’s confusion began curdling into something darker. Men started shouting questions. What knowledge? What demonstration? What’s in the letter? Whitmore raised his hand for silence, then continued reading, and the words that followed would be whispered about in Montgomery parlors for years afterward, always in voices too low for servants to overhear.

The seller states that the property in question possesses complete and perfect recall of every document, ledger, letter, contract, promisory note, deed, will, and financial record she has ever observed. Her memory operates with precision equivalent to photographic reproduction. She can recite word for word, page by page, any text she has seen, regardless of complexity or length.

She can reproduce numerical calculations, account balances, and transaction details years after initial observation. This capacity has been tested extensively and found to be without error or limitation. A new quality of silence claimed the auction floor. This one heavy with implications that every man present understood immediately.

In an economy built on credit, where vast fortunes rested on paper promises, where property deeds might be disputed and debt obligations conveniently forgotten, where wills could be challenged and contracts reinterpreted. A person with perfect memory of financial documents represented power of a type that transcended ordinary commercial value.

Whitmore wasn’t finished reading. The seller further states that during her years of service in various households and commercial establishments in Montgomery and surrounding counties, the property has been present during the preparation, review, and storage of thousands of documents, many of which their creators believed were private or would remain confidential.

She has observed account books, personal correspondence, financial agreements, and other materials whose contents, if disclosed to interested parties, would prove valuable beyond easy calculation. Now the implications became explicit and the auction floor erupted into chaos. Men were shouting, some in anger, some in fear, some with a kind of hungry excitement that suggested they were already calculating what they might gain from possessing this walking archive of secrets.

Others were pushing toward the exits, their faces pale, presumably terrified that their own documents might be among those this woman had memorized. Silas Whitmore waited for the noise to subside, then delivered the final and most disturbing portion of the seller’s statement. The property will cooperate fully with her legal owner, providing any information requested in complete and accurate detail.

She has been conditioned to understand that her well-being depends entirely on her usefulness and discretion. The seller guarantees the accuracy of all information she provides and accepts no responsibility for consequences arising from her owner’s use of such information. The opening bid remains $8,000.

Do I hear $8,000 for 10 seconds? No one moved. Then a hand rose in the back of the room belonging to a cotton factor named James Dloqua whose operations extended across four counties. 8,000,” he said, his voice steady. 9,000 came immediately from another bidder, a merchant banker named Thomas Sheridan, who handled loans for half the plantations in the Black Belt.

What followed was unlike any auction Silus Whitmore had ever conducted. The bidding escalated with terrifying speed, driven not by commercial calculation, but by fear and desperate hunger for the power this woman represented. 10,000, 12,000, 15,000 men who had come to purchase field hands found themselves competing for something infinitely more dangerous.

A human being who contained enough secrets to destroy reputations, bankrupt families, and overturn property claims that had seemed secure for generations. At $18,000, only five biders remained, and the crowd had divided into two groups. Those still competing, their faces showing the strain of betting their entire financial futures on a single purchase.

And those watching with expressions ranging from horror to grim satisfaction, understanding that whoever won this auction would become the most dangerous man in Montgomery. Armed with knowledge that could be weaponized in a thousand different ways. $20,000 announced a man whose identity would remain disputed for years afterward.

He stood near the sidewall, his face partially obscured by the brim of a planter’s hat. his clothing suggesting wealth, but offering no clues about his specific occupation or origin. His voice carried absolute certainty, the tone of someone placing a final bid they knew could not be exceeded. The four remaining competitors looked at each other, performing rapid mental calculations about credit limits and available capital and whether any amount of potential blackmail value justified financial suicide. One by one, they

lowered their hands, their faces showing relief mixed with something that might have been disappointment or might have been terror at what they had almost purchased. Silas Whitmore brought his hammer down, sold to the gentleman against the wall for $20,000. Please come forward to complete the transaction. The winner moved through the crowd with deliberate slowness, and as he approached the platform, men stepped aside, creating space around him as though proximity might prove dangerous.

Up close, he appeared to be in his late 40s with the weathered face of someone who spent considerable time outdoors, but the soft hands of a man who didn’t perform physical labor himself. His clothes were expensive, but not ostentatious, the kind of careful anonymity that wealthy men sometimes cultivate when they don’t want to be remembered.

The transaction took 90 minutes to complete. Bank drafts had to be verified, ownership papers prepared, and duplicate. Witnesses secured for signatures that would make everything legal under Alabama law. During this entire process, the woman designated property number 47 stood motionless on the auction floor, her expression never changing, her eyes still fixed on that invisible point beyond the assembled crowd.

Several men tried to speak to her, asking questions about what documents she might have seen, what families she had served, what secrets she might possess. She never responded, never even acknowledged their presence. Maintaining a silence so complete it seemed almost supernatural. When all paperwork had been finalized, the buyer produced a key and unlocked the iron cuffs binding her wrists.

The metal fell away, leaving red marks on her skin that she didn’t bother to rub. He handed her a folded shawl, which she draped over her shoulders with movements suggesting long practice, then gestured toward the side door. She walked beside him without hesitation, her posture unchanged, and together they disappeared into the October morning, leaving behind a crowd that would argue for hours about what they had just witnessed and what it might mean.

3 days later, inquiries began circulating through Montgomery’s commercial district. Men wanted to know the buyer’s identity, where he had taken his purchase, what he intended to do, with knowledge that could potentially destroy half the prominent families in Alabama. The bank that had verified his drafts confirmed only that the funds were legitimate, drawn on an account registered to a timber company operating in the northern part of the state.

The company’s listed address corresponded to a lumber mill that had been closed for 2 years. The name on the account, Marcus Webb, appeared on no tax roles, no property deeds, no business registrations anywhere in Alabama. The five witnesses mentioned in the seller statement could not be located, though courthouse records confirmed that Judge Harrison Mitchell had indeed notorized a document on October 4th.

When a lawyer attempted to examine this document, he discovered it had been sealed by judicial order, inaccessible without a court mandate that no judge seemed willing to issue. The seller’s identity remained equally mysterious. The three men who had escorted the woman to the auction disappeared immediately afterward and were never identified.

But the most disturbing development came from the woman’s past itself. Because once people began investigating her history, they discovered something that should have been impossible. Over the next several weeks, fragments of her story emerged from sources who insisted on anonymity. Each piece adding to a picture that grew more troubling with every detail.

Her name, according to those who had known her before the auction, was Delilah, though whether this was a birth name or one assigned by owners remained unclear. She had belonged to at least seven different households during her life, passed from owner to owner through sales, inheritances, and debt settlements, a pattern common enough for enslaved people whose existence was treated as transferable property.

But what made Delilah’s trajectory unusual was the specific type of household that repeatedly acquired her. She had spent time in the home of Montgomery’s most prominent attorney, where she worked as a household servant, but was frequently present in his office during client meetings and document preparation. She had belonged to a cotton factor who kept detailed account books, tracking credit extended to dozens of planters, and she had been in the room when these books were reviewed and updated.

She had served in the household of a judge whose personal library contained land deeds and property surveys dating back to Alabama’s territorial period, documents [snorts] that established ownership claims for thousands of acres. She had worked for a merchant banker who processed loans and mortgages, and she had been present during negotiations where men pledged their plantations as collateral against gambling debts they had no realistic prospect of repaying.

In each household, she had been valued for qualities that seemed unremarkable at the time. She was quiet, unobtrusive, efficient at domestic tasks, and possessed what owners described as an unusual stillness that made her easy to forget. People would discuss confidential matters in her presence, review private documents while she cleaned the room, negotiate sensitive agreements while she served tea, never considering that her silence might conceal attention rather than ignorance.

After all, she was illiterate, or so they believed. Enslaved people weren’t taught to read. They couldn’t possibly understand the significance of contract language or property boundaries or account balances that determined who owned what and who owed whom. Except Elila could read. She had taught herself somehow.

Perhaps by observing lessons given to white children in households where she worked, perhaps through access to books left carelessly within reach. perhaps through assistance from someone who violated Alabama law by helping an enslaved person acquire forbidden knowledge. And she possessed something beyond literacy, something that couldn’t be taught or learned, only discovered with horror by those who encountered it.

Her memory operated with a precision that seemed to violate natural law. The first person to document this capability was a plantation owner named Richard Thornnehill, who had purchased Delilah in 1853 when she was approximately 30 years old. Thornneahill operated a medium-sized cotton plantation in Loun County, and he bought Delilah to work as a house servant.

Attracted by reports that she was reliable and required minimal supervision, she worked in his household for 8 months without incident, performing her duties competently, maintaining the same quiet demeanor that had characterized her service in previous households. Then one evening in March of 1854, Thornnehill made a discovery that would eventually lead to Delilah’s appearance on the Montgomery auction block two and a half years later.

He had been reviewing account books in his study, trying to reconcile a discrepancy in his cotton sales from the previous season. The numbers didn’t match his memory, suggesting either an error in his bookkeeping or possible theft by his factory in Mobile. He spent hours searching through correspondents and receipts, growing increasingly frustrated until Delilah entered the room to clear his tea service.

Without thinking, he asked her a question he would regret for the rest of his life. Where did I put that letter from Mobile? The one about the October cotton shipment. Delilah paused, her hands still holding the tea tray, and for the first time in 8 months, she spoke more than a simple yes sir or no sir response.

The letter is in the drawer of your desk, third from the top, filed behind correspondence from your brother. It arrived on October 19th. Your factor wrote that he had sold 17 bales at 9 per pound for total proceeds of $84,360 minus his commission of 6%, leaving a balance of $792.98 to be credited to your account. Thornhill stared at her, confusion giving way slowly to comprehension, then to something approaching fear.

The letter she described was from 4 months earlier. She had been in the room when he read it once, but only once, and he had never discussed its contents with anyone. Yet, she had just recited specific financial details with precision that matched the letter exactly because he found the document where she said it would be and confirmed every number she had provided.

Over the following weeks, Thornhill tested her repeatedly, asking about documents she had been present for, correspondents he had reviewed in her presence, account books she might have glimpsed while cleaning his study. Every test produced the same result. She could recite pages of text word for word. She could reproduce columns of numbers with perfect accuracy.

She could describe documents she had seen once, months, or even years earlier with detail that exceeded his own memory of the same materials. Thornneahill understood immediately what he possessed. Delila wasn’t just a house servant with unusual memory. She was a walking archive of every document she had ever observed. And given her history of service in households and businesses across Montgomery, she potentially contained enough financial information to rewrite the economic landscape of central Alabama. She knew who owed what to whom.

She knew which property deeds contained errors that could be exploited. She knew which men had signed contracts they later denied, which accounts contained fraudulent entries, which fortunes rested on paper claims that wouldn’t survive legal scrutiny. Richard Thornneahill was not a particularly moral man, but he possessed enough imagination to recognize danger when it presented itself.

He understood that owning Delilah made him powerful, but it also made him a target. Every person whose secrets she held would have motivation to either acquire her or eliminate her. Every competitor who learned about her capabilities would seek to purchase her regardless of cost. And if word spread too widely, some might decide the safest solution was simply to kill her, erasing the archive before its contents could be weaponized.

Thornhill kept Delila’s abilities secret for nearly a year, using her selectively to gain advantage in business negotiations. When he needed to recall specific contract terms during a dispute, he would consult her privately, then present the information as though it came from his own memory or documents he had reviewed.

When questions arose about property boundaries, he would have Delila describe survey records she had seen years earlier, giving him leverage and settlement negotiations. He made a considerable amount of money through these consultations, enough to expand his plantation holdings substantially. But Thornhill also began drinking more heavily, sleeping less soundly, and exhibiting paranoia about visitors to his property.

He started keeping Delilah locked in a storage room when guests came to the plantation, afraid that someone might recognize her value if they observed her too closely. He fired three overseers in 6 months, convinced they were spying on him or planning to steal his property. His wife began complaining to relatives that Richard was becoming unbalanced, obsessed with some secret he refused to explain.

In August of 1855, Thornneahill made the decision that would seal his fate. He took Delilah to Montgomery and approached several prominent men with a proposal. He would rent them access to her memory for substantial fees, allowing them to consult her about documents and records relevant to their business interests. He believed this arrangement would spread the risk, making him less of a target while still profiting from what he owned.

The proposal had the opposite effect. Once people understood what Delilah represented, they didn’t want to rent access. They wanted to own her completely to control her knowledge. Absolutely to prevent anyone else from using her memory against them. Within weeks, Thornhill began receiving offers to purchase Delila, some accompanied by barely veiled threats about what might happen if he refused to sell.

His plantation was burglarized twice in September. His cotton warehouse suffered a suspicious fire in October. In November, someone shot at him from the treeine while he was riding his property. The bullet passing close enough that he felt the wind of its passage. Richard Thornnehill broke under the pressure.

In December of 1855, he sold Delilah to an intermediary for $12,000, a fortune that should have represented triumph, but instead felt like escape from a trap he had built for himself. He took his wife and children and left Alabama within a month, relocating to Kentucky, where he purchased a small tobacco farm and lived quietly under an assumed name until his death from pneumonia in 1862.

He never spoke publicly about Delilah or what he had discovered about her capabilities, and his family maintained this silence even after emancipation made such revelations legally safe. The intermediary who purchased Delilah from Thornhill was an attorney named Samuel Crawford, a man whose practice specialized in the kind of discreet services that wealthy families required when scandals threatened their reputations.

Crawford understood that Delila represented something unprecedented, a commodity whose value lay not in labor, but in information, and information of a type that could never become public without destroying its worth. He spent nine months consulting with various parties about what to do with her, how to extract maximum value while managing the enormous risks her knowledge represented.

Samuel Crawford’s consultations led him to a conclusion that would prove catastrophic for everyone involved. Rather than selling Delila to a single buyer who would monopolize her knowledge, he decided to auction her publicly, creating competition that would drive the price to unprecedented levels while simultaneously ensuring that multiple powerful men understood exactly what was being sold.

The auction would serve as both a sale and a warning, demonstrating that secrets existed and could be purchased. That no private document remained truly private if the wrong person had observed it. That the entire structure of credit, debt, and property claims in Alabama rested on assumptions about confidentiality that might no longer hold.

Crawford spent weeks orchestrating the event, sending discreet messages to men whose business interests made them likely buyers, arranging for Judge Mitchell to notoriize the seller’s statement, ensuring that everything would be legal and binding under Alabama law. He understood that the auction would create chaos, but chaos, he believed, could be profitable for someone positioned correctly to exploit it.

What Crawford failed to anticipate was that some secrets are too dangerous to be sold. that knowledge of certain types carries a weight that crushes everyone who touches it, and that the men competing for Delilah weren’t bidding on a commodity they hope to profit from. They were bidding to prevent others from acquiring a weapon that could destroy them.

The man who purchased Delila for $20,000 was named Marcus Webb. And that much at least was true, though everything else about him was carefully constructed fiction. He was not a timber company owner. He operated no business in northern Alabama. He was something far more dangerous. a professional blackmailer who had spent 15 years building a network of informants and compromised sources across the South, accumulating secrets the way other men accumulated land or cotton bales.

And he had been searching for someone like Delilah for most of his career. Webb understood immediately what Crawford’s auction represented. It wasn’t just a sale of one unusually valuable piece of property. It was a revelation that perfect memory existed, that a human archive walked among them, containing information that powerful men believed was safely buried in private correspondents and locked account books.

And Web understood something else that Crawford had been too greedy to realize. The auction itself was Delila’s death sentence because once everyone knew what she contained, she became too dangerous to be allowed to live. Webb’s purchase was not an investment. It was a rescue operation. Though whether he intended to rescue Delilah or simply to rescue the secrets she held remained ambiguous, even to him, he took her from Montgomery within hours of the auction’s conclusion, traveling by hired carriage north toward the Tennessee

border, moving quickly enough to stay ahead of anyone who might be following. He had arranged a temporary refuge, a farmhouse in Limestone County owned by an associate who asked no questions and kept no records of visitors. They arrived after dark on October 10th. Webb had said almost nothing during the journey, and Delilah had maintained her characteristic silence, sitting across from him in the carriage with that same unsettling composure she had displayed on the auction block.

But once they were inside the farmhouse with lamps lit and the door secured, Webb finally addressed her directly, speaking to her as a person rather than property for the first time since the transaction had been completed. “You understand what’s about to happen,” he said. “It wasn’t a question.” Delilah looked at him with eyes that contained no fear, no hope, no emotion he could identify, she nodded once.

“The men who bid against me won’t accept this outcome,” Webb continued. “Some of them carry secrets you’ve memorized, and they can’t allow you to exist as someone else’s property. They’ll come for you. Some will offer money. Some will offer threats. Some will simply try to kill you and anyone protecting you. You’ve become the most dangerous person in Alabama.

” Delilah spoke for the first time since the auction. Her voice quiet but perfectly clear. I’ve always been the most dangerous person in Alabama. They just didn’t know it until today. Webb stared at her, recalibrating his understanding. He had assumed she was a victim of circumstance, someone whose unusual abilities had trapped her in a situation beyond her control.

But the way she spoke suggested something different, a deliberation that implied choice rather than accident, strategy rather than misfortune. “You wanted this,” he said slowly. “You wanted to be sold publicly. You wanted everyone to know what you can do.” Delilah smiled then, and it was the expression that witnesses at the auction had tried to describe, something that looked like satisfaction, but felt like watching a blade slide between ribs.

Knowledge requires payment, she said. They’ve been extracting value from me for 15 years, using my memory to resolve their disputes, settle their debts, confirm their property claims. They treated me like a tool, something to be consulted when convenient, and forgotten when not. So, I decided to show them exactly what I am. Not a tool, a weapon.

And now they’ll pay the price for every secret I’ve collected. Webb felt something cold settle in his chest. What price? Delilah walked to the window, looking out at darkness that concealed whatever watchers might already be positioning themselves around the farmhouse. They think owning me gives them control over the secrets I hold.

But information doesn’t work that way. Once people know that secrets can be remembered perfectly once they understand that no private document stays private if the wrong person observes it. Trust becomes impossible. How does a planter negotiate with his factor if he knows their conversation might be recorded in someone’s flawless memory? How does a banker extend credit if he worries his account books might be memorized by a servant present in the room? How do any of them continue operating in a world where privacy is

revealed to be an illusion? She turned back to face web and her expression held something that might have been satisfaction or might have been grief. I’m not a weapon you can point at your enemies. I’m a weapon that’s already detonated. The damage is done. The auction did what I needed it to do. Now we just watch while everything collapses.

Over the following weeks, Marcus Webb discovered that Delila had been absolutely correct. The auctions aftermath rippled through Montgomery’s commercial society like cracks spreading through glass under pressure. Men who had bid on Delilah but lost began demanding investigations into what secrets she might possess about their business rivals.

Those who hadn’t bid started wondering what information she held about them, what documents she might have observed during her years of service in prominent households. Paranoia spread faster than yellow fever. Lawyers who had discussed confidential client matters in front of household servants suddenly worried about who had been listening.

Bankers began relocating their account books to secure locations as though this would somehow erase the fact that these books had been reviewed in the presence of people they had treated as furniture. Planters started challenging property deeds and debt obligations, claiming their opponents had somehow gained access to privileged information, though they could never explain how.

3 weeks after the auction, James Dilqua, the cotton factor, who had bid $8,000, was found dead in his Commerce Street office. The coroner ruled it suicide by gunshot, noting the weapon in Dloqua’s hand and the letter on his desk explaining his decision. The letter mentioned financial reversals and personal despair, but friends who read it recognized that Delicacross handwriting seemed unsteady, as though written under duress.

His account books, which should have contained records of credit extended to dozens of planters, had been removed from the office and were never recovered. In November, Thomas Sheridan, the merchant banker who had bid 9,000, fled Montgomery undercover of darkness, leaving behind a wife and three children who claimed to know nothing about his destination or reasons for departure.

His bank discovered irregularities in several loan accounts, suggesting he had been embezzling for years, but the evidence seemed too convenient, too perfectly documented, as though someone had arranged for these discoveries specifically to drive Sheridan into exile. The third death came in December. A planter named William Crane, who had bid to 12,000 before dropping out, was killed when his carriage overturned on a road he had traveled safely for 20 years.

The accident occurred at night on a curve where someone had strategically weakened the road surface, though no investigation could determine who might have done this or why. Crane’s widow found among his effects a letter he had apparently been writing before his death, describing his conviction that he was being watched, that someone was targeting men who had participated in the auction, that the only safety lay in leaving Alabama entirely.

He never finished the letter. But the most disturbing development came from something that didn’t happen. Marcus Webb and Delilah vanished completely. No one could locate them. No one could trace their movements. It was as though the earth had opened and swallowed them both, leaving behind only questions and a growing conviction that the auction had unleashed something that could not be controlled or contained.

Rumors multiplied with the speed that characterizes frightened communities. Some claimed Webb had taken Delilah North, selling her secrets to politicians in Washington who wanted leverage over southern congressmen. Others insisted he had murdered her immediately after the purchase, understanding that she was too dangerous to be kept alive, that her knowledge represented a liability that outweighed any potential profit.

A particularly persistent story suggested that Delilah had killed Webb within days of the auction, then assumed a new identity and disappeared into the free black communities of northern cities, carrying her archive of secrets to a place where Alabama’s laws couldn’t reach her. The truth, when it emerged years later, proved more disturbing than any of the rumors because it revealed that Delilah had been playing a longer game than anyone suspected, that the auction had been merely one move in a strategy that stretched across decades, and that the

price she mentioned, the payment knowledge required, was far higher than the $20,000 Marcus Webb had bid. In 1864, during the chaos of Sherman’s approach toward Atlanta, a Union officer named Colonel Benjamin Hastings received an unusual visitor at his headquarters. A woman of mixed race, approximately 45 years old, appeared at his camp requesting an interview.

She carried papers identifying her as a free person. Documents that appeared legitimate, if slightly questionable, the kind of careful forgeries that occupied a gray zone between legal and criminal. The woman said her name was Delilah Webb and she claimed to possess information that would be valuable to Union intelligence.

She said she had spent years in Montgomery, Alabama, working in households and businesses where Confederate officers and government officials had discussed strategy, troop movements, supply lines, and financial arrangements with European bankers who were providing credit to keep the rebellion functioning.

She said she could remember these conversations perfectly, recall them word for word, reproduce documents she had observed that detailed the Confederacy’s financial vulnerabilities and strategic weaknesses. Colonel Hastings was skeptical initially, but he agreed to test her claims. He showed her a captured Confederate dispatch, let her read it once, then asked her to reproduce it.

She recited the entire document from memory, including details about troop positions and supply requisitions without a single error. Hastings brought in other officers who questioned her about Alabama geography, prominent families, business relationships that might be useful for intelligence purposes. Her answers demonstrated knowledge that seemed impossible for someone of her race and gender to possess, but everything she told them checked against information obtained through other sources.

Are you offering this as commentary on the powerful, keeping their discussions private, even though servants are present and listening, and how this knowledge becomes dangerous? Let me continue with part 3’s conclusion and move toward part four. Hastings made a decision that would alter the course of several military campaigns.

He brought Delilah to Washington, introduced her to senior intelligence officers, and arranged for her to be debriefed systematically about everything she had observed during her years in Montgomery. The information she provided proved devastatingly accurate. She described cotton shipments being diverted through Mexico to European buyers, providing the Union Navy with specific routes and timing that allowed them to intercept critical Confederate revenue.

She detailed conversations between Alabama politicians and British textile manufacturers, revealing which families were most vulnerable to financial pressure. She identified Confederate sympathizers operating in border states, people whose loyalties remained secret, but whose correspondence she had memorized while serving in households where such letters were reviewed.

The intelligence Delilah provided contributed directly to Union victories that shortened the war by an estimated 6 months, saving thousands of lives while simultaneously destroying the economic foundation that had sustained the Confederacy’s military operations. And she did all of this while maintaining the same unsettling composure she had displayed on the Montgomery auction block 8 years earlier, providing information with mechanical precision, never showing emotion, never revealing whether she took satisfaction from the devastation

her knowledge was causing to the families that had owned her. When the war ended, Delila disappeared again. The Union Army had no further use for her, and she possessed enough money saved from her intelligence work to purchase genuine freedom documents and establish herself anywhere she chose. Some records suggest she lived in Philadelphia for several years.

Others place her in Boston or New York. A few fragmentari sources claim she traveled to Canada where she worked as a tutor teaching, reading, and writing to children of formerly enslaved families. Though whether this particular detail is accurate remains uncertain, the most complete account of Delilah’s later life comes from an unexpected source, a private journal kept by Margaret Holloway, the same historian who investigated the Richmond exchange sale.

In 1893, while researching enslaved people’s contributions to Union intelligence operations, Hle discovered references to a woman matching Delilah’s description, who had provided information to Colonel Hastings. This led her to Montgomery where she spent three months examining what remained of courthouse records and conducting interviews with elderly residents who remembered the October 1856 auction.

Most refused to speak about it. Even 37 years after the event, even decades after emancipation had made such conversations legally safe, people treated the auction as something shameful that decent society should never acknowledge. But Hle was persistent and eventually she found a source willing to talk, an elderly black woman named Sarah Mitchell who had worked as a seamstress in Montgomery during the Antibbellum period and had known Delilah personally.

Sarah was 71 years old when Hle interviewed her in November of 1893. Her memory remained sharp, and she spoke with the careful precision of someone who had spent a lifetime weighing her words, understanding that speaking truth as a black woman in Alabama carried risks that never entirely disappeared, regardless of what laws claimed.

Delilah wasn’t her real name, Sarah explained. Her mother named her diner after someone in the Bible, but owners kept changing it depending on what they thought sounded appropriate. She stopped caring what they called her after a while. said, “Names were just another thing white people took from you, so why get attached to anything you couldn’t keep?” Holloway asked how Delilah had learned to read, where she had acquired the education that made her memory so dangerous.

Sarah’s expression grew cautious, but after a moment, she continued, “There was a white woman in Montgomery, a Quaker from Pennsylvania, who married a merchant here. She believed slavery was evil, and she did something about it, even though it was illegal. She taught reading to enslaved people secretly, usually at night, in the back room of a shop her husband owned.

Delila went to those lessons for nearly 2 years, starting when she was maybe 13 or 14. Learned to read, learned to write, learned arithmetic and geography and history. The Quaker woman said Delila was the most brilliant student she’d ever taught, white or black. said her memory was like nothing she’d encountered that Delilah could read something once and recited perfectly weeks later.

“What happened to the Quaker woman?” Hle asked. Sarah’s face hardened. Someone informed on her in 1843. She was arrested, tried for violating Alabama’s education laws, and sentenced to 6 months in jail. Her husband divorced her while she was imprisoned, took their children north, and never came back. She died of fever in that jail 3 weeks before her sentence would have ended.

They buried her in the porpa cemetery outside town. Didn’t even mark the grave properly. But before she died, she got a message to Delilah. Told her to use what she’d learned to make the knowledge worth something to make them pay for what they’d stolen. And Delilah did. Hle said quietly. Sarah nodded. Oh yes, Delilah did exactly that.

She spent the next 13 years positioning herself, getting sold to specific households, making herself useful enough that owners would keep her around, but forgettable enough that they’d discuss private matters in her presence. She memorized everything, every document, every conversation, every secret that people believed was safe because they’d never considered that an enslaved woman might be listening, understanding, and remembering with perfect accuracy.

But she didn’t use that knowledge immediately. She waited, built up her archive year after year, letting people become comfortable with her presence, collecting more and more information until she possessed enough secrets to destroy dozens of prominent families simultaneously. And then she arranged her own auction, worked with that lawyer, Crawford, to make sure everyone understood exactly what was being sold.

She wanted them terrified. She wanted them to understand that their privacy had been an illusion, that every assumption they made about enslaved people being ignorant or incapable was a lie they told themselves to sleep at night. Holloway leaned forward, her academic training momentarily overwhelmed by the implications of what she was hearing.

The auction was deliberate. She planned to be sold that way. Sarah smiled grimly. Delilah planned everything. She knew the auction would cause chaos, that men would panic, that some would die and others would flee. She knew that trust between planters and factors and bankers would collapse once everyone understood that perfect memory existed.

And she knew the war was coming, even if most white people were too blind to see it. She positioned herself to be valuable to whichever side won. And when the Union needed intelligence, there she was with exactly the information they required. The greatest revenge, Sarah continued, her voice dropping to barely above a whisper.

Wasn’t what she did during the war. It was what she did after. When Delilah finally became free, truly legally free. She started writing letters, sent them to families across Alabama, people whose secrets she’d memorized years earlier. The letters were polite, carefully worded, but the message was clear. She remembered everything.

She could prove debts that had been conveniently forgotten, property transfers that had never been properly recorded, agreements that violated laws if they became public. She didn’t ask for money explicitly. She just reminded them that she existed, that her memory existed, and that memory doesn’t die just because the war ended. Some families paid her, H said, understanding dawning. Sarah nodded.

Oh yes, paid her regular amounts quarterly or yearly. purchasing silence about things their grandfathers and fathers had done. Not all of them. Some refused, thought they could ignore a black woman’s claims, regardless of what she knew. Those families tended to have unfortunate things happen. Property deeds that got challenged successfully in court.

Business partnerships that fell apart when old disputes resurfaced with perfect documentation. Reputations that crumbled when letters appeared in newspapers describing transactions people had sworn never occurred. Delilah lived well in her later years, very well by anyone’s standards. Owned property in three different cities, dressed in clothes that would have been appropriate for a wealthy white woman, traveled wherever she pleased.

Some people whispered she was being supported by a patron, some white man who’d taken her as a mistress. But anyone who knew her understood the truth. She was supporting herself through the careful exploitation of knowledge she’d accumulated across decades of being treated as furniture while people discussed matters they believed no one would remember.

If you’re finding this story as powerful as we are, do us a favor. Hit that like button to help others discover Delila’s truth and leave a comment with your thoughts. What would you have done in her position? How should we remember people who use the only weapons available to them in a system designed to keep them powerless? Your engagement helps stories like this reach the people who need to hear them.

Margaret Hole tried to locate Delilah after her conversation with Sarah Mitchell. She sent letters to addresses in Philadelphia, Boston, and New York, where records suggested a woman matching Delilah’s description might have lived. None of the letters received responses. She examined property records, bank accounts, business registrations, searching for any trace of the woman who had sold for $20,000 and then vanished into freedom with enough secrets to sustain her for a lifetime.

The search produced only fragments, hints of presence without confirmation. A property deed in Philadelphia registered to a diner web in 1872. a bank account in Boston belonging to someone with the initials DW who made regular deposits from 1868 through 1889. A mention in a newspaper society column from 1885 describing a well-dressed colored woman who attended an abolitionist meeting and contributed generously when donations were requested.

But Hle never found Delila herself and eventually she abandoned the search. In her private journal she wrote that perhaps Delilah’s greatest triumph was her disappearance. the way she became impossible to track once she gained control over her own story. For 15 years, people had watched her, monitored her movements, treated her presence as something they owned.

Once free, she made herself invisible, except when she chose revelation, appearing only to deliver reminders that memory persists, and debts eventually come due, regardless of what legal structures claim to erase them. The last confirmed reference to Delilah appears in an 1897 letter discovered in the archives of the Freriededman’s Bureau.

The letter, unsigned but written in elegant handwriting that analysis suggests belonged to an educated woman of advanced age describes the experience of being sold at auction and the strategies necessary for survival when you possess knowledge that others fear. The writer never identifies herself by name, but several details match what is known about Delila’s life with precision that suggests either she wrote this letter herself or someone very familiar with her story composed it on her behalf.

The letter’s final paragraph contains words that have been quoted in dozens of historical studies since its discovery because they capture something essential about resistance and memory and the long arc of justice that often moves too slowly for those trapped in its machinery. They believe they owned me.

The letter states, “They believed that purchasing my body gave them rights to what my mind contained. But memory cannot be owned. Knowledge cannot be chained.” I carried their secrets through decades of bondage. And when freedom finally came, those secrets became currency. I spent deliberately carefully extracting payment for every humiliation, every moment of being treated as less than human.

Some call this revenge. I call it accounting. They kept ledgers tracking what they stole from me and millions like me. I simply kept better records and I collected the debt they insisted didn’t exist. Whether Delila wrote these words or someone else did, they represent a truth that extends far beyond one woman’s extraordinary memory.

Throughout the history of American slavery, enslaved people accumulated knowledge about their owners, their owner’s families, their owner’s business dealings, and personal failings. They observed everything while being treated as though they observed nothing. They understood conversations conducted in their presence as though their comprehension didn’t matter.

And sometimes, rarely, but powerfully, they use that knowledge to create space for resistance, to extract small victories from impossible circumstances to demonstrate that the system designed to crush them contained weaknesses that careful observation could exploit. Delila’s story represents an extreme example of this dynamic because her memory operated at a level that seems almost supernatural.

But the principle she embodied exists throughout the historical record, visible in countless smaller moments where enslaved people leveraged information to protect themselves, to help others, to create cracks and structures that appeared unbreakable. Knowledge was one of the few resources that couldn’t be entirely controlled.

one of the few forms of power that surveillance couldn’t eliminate because you can watch a person without ever knowing what they understand about what they’re seeing. The auction on October 9th, 1856 was ultimately about this uncomfortable truth. When Montgomery’s elite gathered to bid on property number 47, they weren’t just purchasing one unusually valuable enslaved woman.

They were confronting the revelation that their power had always been more fragile than they believed. that the people they owned had been watching them just as carefully as they watched those they enslaved, and that memory could be a weapon that waited years or decades before being deployed with devastating effect.

Three of the men who bid on Delila died within 18 months. Two fled Alabama forever. The survivors spent the rest of their lives wondering what she remembered about them, what secrets she might hold, what price she might eventually demand. The auction destroyed trust between planters and factors, between bankers and clients, between anyone whose business depended on confidentiality and anyone who might have observed their confidential dealings.

The economic disruption this caused contributed to Alabama’s vulnerability when war came because credit networks had already been damaged by paranoia about who knew what and who might reveal it. And Delilah walked away free, eventually carrying an archive of secrets that sustained her for the rest of her life, extracting payment from people who insisted they owed nothing, demonstrating that knowledge does indeed require payment beyond gold, and the debt compounds with interest until someone finally settles the account.

Here at the sealed room, we excavate stories like Delilas because they force us to confront uncomfortable questions about power, memory, and resistance. They reveal that the people history tried to erase were often the ones watching most carefully, remembering most accurately, and waiting most patiently for the moment when their knowledge could be transformed into something more powerful than any auction price could represent.

The Montgomery Cotton Exchange building where Delila stood on that October morning was demolished in 1931 to make way for a department store. No historical marker commemorates what occurred there. No monument acknowledges the woman who sold for more than any enslaved person in Alabama history. The auction records, if they still exist, remain buried in courthouse archives that few researchers bother to examine.

But memory persists even when monuments don’t. Stories survive even when official history tries to bury them. And sometimes if you listen carefully to the silences in historical records, to the gaps where someone removed pages from ledgers or sealed documents that might prove too revealing, you can hear echoes of people like Delilah who refused to let their knowledge be stolen without eventually collecting payment.

She told them from the beginning, “Knowledge requires payment beyond gold.” They just didn’t understand that she wasn’t explaining what they would pay to acquire her knowledge. She was explaining what they would pay for having stolen it in the first place. And that bill came due eventually with interest, collected by the woman they believed they owned, but who spent every moment of her bondage preparing for the accounting that would come when freedom made collection possible.

What do you think about Delilah’s story? Was she justified in using the secret she collected to extract payment from families who had owned her? How should we remember people who resisted oppression using the only weapons available to them, even when those weapons were information others believed should remain buried? Leave your comment below with your thoughts.

This is exactly the kind of discussion we want to have here. If you found this investigation as haunting as we did, subscribe to this channel and activate notifications so you never miss the next story we uncover. Share this video with someone who appreciates historical truths that challenge comfortable narratives.

And if you want to go deeper, check out the other investigations we’ve conducted into the buried secrets of American history. The stories that institutions spent generations trying to erase. but that refuse to stay silent. The algorithm rewards videos that get engagement in the first few hours.

It would never be asked. It would never be asked. It would never be asked.