Can we stay overnight, please? My baby sister is really cold. A seven-year-old boy stood in the doorway of a biker clubhouse, snow caked in his brown hair, tears frozen on his cheeks. Behind him, a young woman collapsed to her knees on the icy steps, clutching a newborn wrapped in a soaked blanket.

The baby wasn’t crying anymore. That was the part that terrified everyone inside. 40 Hell’s Angels stared at that doorway and not one of them moved. Not yet.

The boy’s name was Ethan, 7 years old. Brown hair that fell across his forehead in wet clumps, a jacket two sizes too big that used to belong to his father, boots that were soaked through because the snow had been up past his ankles for the last mile and a half.

He was holding his mother’s hand when her legs gave out. Sarah Mitchell went down hard on the steps of the Iron Wolves’s den. And the sound she made wasn’t a scream. It was worse. It was quiet. The kind of sound a person makes when they’ve used up everything they have and there’s nothing left. The baby in her arms shifted.

Lily, 6 days old, born by C-section at St. Mary’s Hospital in Granton. Sarah’s stitches had torn open somewhere around mile 2. She could feel the warmth of her own blood soaking through her shirt beneath her coat. But she didn’t say anything because Ethan was watching. And Ethan had already seen too much for a boy his age.

“Mom!” Ethan pulled at her sleeve. “Mom, get up.” She couldn’t. “Mom, please.” Sarah looked up at the door. The neon sign above it buzzed and flickered. She could read the words through the falling snow. “Hell’s Angels.” Chapter 47. Everything she’d ever heard about men like this told her to keep walking.

Every news story, every warning from her mother, every whispered thing at the grocery store back in Granton. But Lily had stopped crying 10 minutes ago. And Sarah knew. She knew deep in her bones that a silent newborn in a blizzard was a newborn running out of time. “Ethan,” she whispered. “Knock on the door.” He looked at her. His eyes were wide. The biker place.

Knock on the door, baby, hard as you can. He turned, lifted his small fist, and he knocked. Today is a very multiple type of the challenges with her brig. Inside the Iron Wolves’s den, the music cut out like someone had pulled the cord. The room was full, maybe 40 men, some standing around the pool tables, some sitting near the bar, a few by the fireplace playing cards.

The air was thick with cigarette smoke and the smell of leather and engine grease. A country song had been playing on the jukebox. Now there was nothing but the wind outside in the sound of knocking. Small knocking. Not the kind that comes from a fist looking for trouble. The kind that comes from a child.

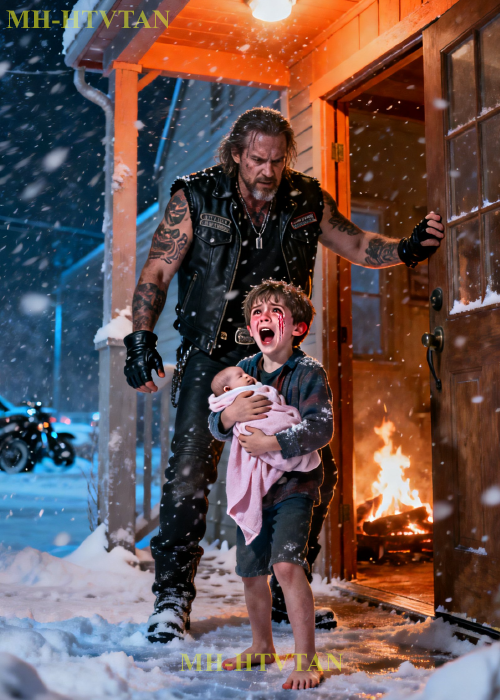

Colt was the one who opened it. He was 6’3, 240 lb, neck tattoos crawling up past his collar. Hands that could crush a beer can without thinking about it. He pulled the door open and looked down. And what he saw made him take a full step backward. A boy shaking, lips blue, snow in his eyelashes. And behind the boy, a woman on her knees holding something small and still against her chest.

“Can we stay overnight?” Ethan said. His voice cracked on the last word. “Please, my baby sister is really cold.” Colt didn’t move. Nobody in the room moved. It was the kind of silence that doesn’t just happen. It’s the kind of silence that falls like a weight dropping through the floor when every person in a room realizes at the same time that something is very, very wrong.

Then a voice came from the back, deep, rough, the kind of voice that had given orders for 20 years and never once had to repeat itself. Move. Gunner Hayes stood up from his chair by the fire. He was the chapter president. 58 years old, gray streaked, brown beard, hands scarred from decades of road and work and things he didn’t talk about.

He wore his leather cut like it was part of his skin. The patches across his back read, “Hell’s Angels, cedar hollow in letters that had faded and been reststitched more times than anyone could count.” He crossed the room in four strides. And when he reached the door, he didn’t ask questions. He didn’t hesitate.

He crouched down, looked at the boy, and said, “How long you been out there?” Ethan’s teeth were chattering too hard to answer. Gunner looked past him, saw Sarah, saw the baby, saw the blood staining through her coat at the hip. His expression changed. “Get them by the fire,” he said. “Now cold, blankets, ace, hot water, bones. Where’s bones here, President?” A lean man with a shaved head and military tattoos on both forearms pushed through the crowd.

Bones real name David Keller, former Army combat medic, two tours in Iraq. He’d pulled shrapnel out of soldiers in the back of a Humvey doing 60 on a dirt road. He delivered a baby in a bombed out building in Fallujah. He wasn’t easily shaken, but when he saw the newborn, he moved fast. Give me the baby, he said to Sarah. She shook her head. Her arms tightened around Lily.

She’s cold. She’s so cold. She stopped crying. She stopped. Ma’am, bones knelt in front of her. His voice was calm, steady, the voice he’d used a hundred times in the field when everything around him was chaos. I was a combat medic, 8 years army. I need to check her temperature and her breathing. I’m not going to hurt her, but I need you to let me hold her right now.

Sarah looked at him. She looked at his face, searching for something. Trust, safety, anything she could hold on to. Bones held her gaze. He didn’t flinch. She let go. She took the baby carefully, unwrapping the wet blanket, and the room went still again. Lily was small, so small. Her skin had a grayish blue tint that made Bones’s jaw tighten.

He pressed two fingers gently against her chest. “She’s breathing,” he said. “Shallow. She’s hypothermic. Core temperatures dropped. We need skin-to-skin contact. And we need it now.” He looked up at Gunner. Warm blankets from the dryer, not the ones on the shelf, the ones that are hot. “And I need someone to hold her against bare skin. Direct body heat.

” “I’ll do it,” Gunner said. Nobody argued. Gunner Hayes, president of the Hell’s Angel Cedar Hollow chapter, a man who had been arrested 11 times, who had ridden through thunderstorms and bar fights and territory wars that would make most men quit, unzipped his leather jacket, pulled off his shirt, and took a six-day old baby girl against his bare chest.

He wrapped his jacket around both of them and sat down by the fire. “Come on, little one,” he murmured. “You stay with us now.” Ethan watched all of it. He stood near the fireplace, a blanket wrapped around his shoulders, a mug of hot cocoa in his hands that a biker named Duke had pressed into his palms. He hadn’t drunk any of it. He was watching the big man hold his sister, and he was trying to understand.

Duke crouched beside him. Duke was 34, built like a refrigerator, arms covered in ink from his wrist to his shoulders. He had a daughter back in Reno he hadn’t seen in 2 years. And that fact burned in his chest every single day. “Hey buddy,” Duke said. “You doing okay?” Ethan didn’t look at him.

“Is Lily going to die?” Duke felt something crack inside his ribs. “Not bone, something deeper.” “No,” he said. “She’s not. That man holding her, that’s our president. He’s the toughest person I’ve ever met. And right now, he’s keeping her warm. She’s going to be just fine. Ethan’s lip trembled.

Promise? Duke put his hand on the boy’s shoulder. I promise. Ethan took a sip of the cocoa. Then he said quietly. My dad used to say the same thing. He used to say, I promise. When he meant it for real. Duke swallowed hard. Your dad sounds like a good man. He was a soldier. Ethan’s voice was so matterof fact that it hit harder than tears.

He died in Afghanistan 8 months ago. Mom says he’s watching us from somewhere. I don’t know if that’s true, but I talk to him sometimes anyway. Duke turned his face away so the boy wouldn’t see his eyes. He stared at the fire for a long moment. Then he said, “I think he can hear you, kid. I really do.” On the other side of the room, Bones was working on Sarah.

He’d gotten her onto a bench near the wall, away from the crowd. Her coat was off. The left side of her shirt was dark with blood. He lifted it carefully and saw what he’d feared. The C-section incision had partially reopened. “Not catastrophically, but enough.” “When was the surgery?” he asked. “And you were driving in this in a blizzard? 6 days posttop?” Sarah’s eyes filled with tears and she looked away.

I didn’t have a choice. Bones opened his kit, an old military field bag he kept at the clubhouse for emergencies. Gauze, antiseptic, butterfly strips. He cleaned the wound carefully. This needs stitches, real ones. But I can close it enough to hold for now. It’s going to sting. I don’t care about the sting.

She grabbed his wrist. My baby, how bad is it? Bones looked at her straight. She’s hypothermic. That means her body temperature dropped below what’s safe. Gunner’s doing skin-to-skin right now. That’s the best thing for her. It’s what they taught us to do in the field with infants and trauma patients.

Body heat transfers faster than any blanket. She’s breathing. Her heart rate is there. She’s fighting. She’s only 6 days old. She doesn’t know how to fight. UD surprised. Bones applied the butterfly strips with steady hands. Newborns are tougher than people think. She made it this far. That tells me she’s got her mother in her. Sarah broke.

Not loudly, not dramatically. She just put her hand over her face and her shoulders shook. And the sound that came out of her was the kind of crying that has no breath behind it because it’s been held in too long. Bones didn’t try to stop her. He just kept working. Sometimes the best thing a medic can do is let someone fall apart while you hold them together.

20 minutes passed. Lily made a sound. Small, a whimper, then a faint, thin cry. The entire room heard it. Gunner looked down at the baby against his chest. Her color was changing. The grayish blue was fading, replaced by pink. Her tiny fists clenched and unclenched. Her mouth opened and closed, searching. “She’s hungry,” Gunnar said.

There was something in his voice that nobody in that room had ever heard before. Not the president. Not the shot caller. Not the man who’d stare down rival clubs without blinking. Something softer. Something raw. She’s okay. She’s hungry. Bones cross the room. Checked her pulse, her breathing, the color of her nail beds. He exhaled slowly.

Temperature is coming up. She’s stabilizing. He looked at Gunner. You just saved this baby’s life. Press. Gunner didn’t say anything. He just held Lily a little tighter and nodded once. Sarah was at his side in seconds, reaching for her daughter. Gunner transferred the baby gently, carefully like she was made of something more precious than glass.

Sarah pulled Lily to her chest and pressed her face against the baby’s head and breathed in. And for a long moment, the world stopped turning for her. Everything stopped. There was just this. her daughter alive, warm, crying. Crying was good. Crying meant alive. Thank you, she whispered to Gunner. Thank you.

I don’t don’t, he said gently. You don’t need to thank me for that. Not ever. Ethan appeared at his mother’s side, pressing close against her. He reached out and touched Lily’s hand. The baby’s fingers curled around his index finger, and Ethan laughed. the first laugh any of them had heard from him. She’s strong, Mom. Feel that grip? Sarah smiled through her tears. She gets that from your dad.

The room was different now. Something had shifted. The bikers who had been standing back watching, uncertain, they moved closer. Not crowding, just present. Ace brought Sarah a plate of food. Colt refilled Ethan’s cocoa without being asked. A biker they called wrench dragged a mattress out of the back room and set it up near the fire.

“For you and the kids,” he said gruffly, not looking at her. “It ain’t much. It’s everything,” Sarah said. Gunner pulled his shirt back on, zipped his jacket, and walked to the window. “The blizzard was worse now. He couldn’t see the parking lot, couldn’t see the road. He could barely see the neon sign 10 ft from the glass. Colt came up beside him.

Hell of a night, press. Yeah. Where’d they come from? I don’t know yet. Gunner turned from the window, but I intend to find out. He pulled up a chair across from Sarah. She was sitting on the mattress now, Lily nursing under a blanket. Ethan curled up beside her with his eyes half closed. Gunner sat down slowly, elbows on his knees.

“Ma’am, I’m Gunner. I’m the president of this chapter. You’re safe here tonight and tomorrow and as long as you need. Nobody in this room is going to hurt you or your children. You have my word on that and my word is the only currency I deal in. Sarah studied him. Sarah, she said, Sarah Mitchell.

Sarah, can you tell me what happened? How’d you end up on foot in the worst storm this county seen in 15 years? She exhaled slowly. The story came out in pieces. She’d been living in Granton, a small apartment. Jake, her husband, had been Staff Sergeant Jake Mitchell, Third Infantry Division, killed by an IED outside Kandahar 8 months ago.

She’d had the notification at the door, two officers, a folded flag. Ethan had been standing behind her in his pajamas. After Jake died, everything collapsed. The military benefits took months to process. She couldn’t work because of the pregnancy. The landlord in Granton raised the rent. She sold everything she could. Jake’s tools, the TV, his guitar.

When Lily was born, Sarah knew she couldn’t do it alone anymore. Her mother, Donna, lived in Pine Ridge, 90 mi north. Donna didn’t know about the baby. Sarah had wanted to surprise her. Wanted to show up at her mother’s door with Ethan and a newborn grandchild and say, “We’re home, mama. We need you. She left Granton at noon.

The forecast said light snow. By 3:00, it was a blizzard. By 4:00, she couldn’t see the road. The car, an old Honda Civic with bad tires, hit a patch of ice on Route 9 and slid off the highway into a drainage ditch. The axle snapped. The engine died. No cell signal. No other cars. Temperature dropped.

She waited 30 minutes hoping someone would pass. Nobody did. Lily started crying. Then Lily stopped crying and Sarah knew that staying in that car meant dying in that car. So she got out, strapped Lily to her chest, took Ethan’s hand, and started walking. “How far did you walk?” Gunner asked. His voice was quiet. “I don’t know, 2 miles, maybe three.

” Ethan didn’t complain once, her voice cracked. He carried the diaper bag the whole way. Didn’t drop it. He kept saying, “I got it, Mom. I’m the man of the house now. Dad said so.” Gunner was quiet for a long time. He looked at Ethan, who had fallen asleep against his mother’s arm, his small chest rising and falling peacefully.

Then he looked back at Sarah. “Your husband, what was his name?” “Jake. Staff Sergeant Jake Mitchell.” Gunner nodded slowly. “Ma’am, I want you to know something. Three of the men in this room served. Bones did two tours in Iraq. Colt was Marines. I did four years Army, 82nd Airborne before I found the club. Your husband’s sacrifice means something to us.

It means a lot. Sarah’s chin trembled. He would have walked through that blizzard himself if he had to. He never would have quit. No, Gunner said. And neither did you, and neither did that boy, he stood up. You get some sleep. Bones is going to check on the baby every hour and in the morning we’ll figure out how to get you to your mother’s.

He started to walk away. Sarah’s voice caught him. Gunnar. He turned. The people in Granton, they told me to stay away from places like this. They said men like you were dangerous. Gunner looked at her for a long beat. Then the faintest smile crossed his face. We are, ma’am, just not to you. The fire crackled low.

The bikers settled in for the night, but nobody left. Not one. 40 men stayed in that clubhouse through the worst blizzard Cedar Hollow had seen in a decade, and they stayed because there was a mother and two children sleeping by their fire. Bones checked Lily at midnight. Her temperature was normal. Her breathing was strong.

He told Gunner, who was standing by the window again, watching the storm. She’s good. President baby’s stable. And the mother wounds holding. She needs a real doctor when this clears, but she’ll make it. Gunner nodded. Good. Bones hesitated. Pres, you know Pineriidge is 90 mi from here. I know.

Roads are going to be a disaster. You’re thinking about taking them yourself, aren’t you? Gunner didn’t answer right away. He pulled out his phone and checked the weather. The storm was supposed to break by dawn. Clear skies by morning, but the roads would be buried. I’m not thinking about it, Gunner said. I’m doing it.

Bone stared at him. 90 miles in the dead of winter on cleared roads that won’t be cleared. Then we’ll clear them ourselves. That’s insane, Gunner. Probably. He looked back at the sleeping family by the fire. The boy’s arm was draped protectively over his baby sister, even in sleep. But that kid walked through a blizzard carrying a diaper bag because his dead father told him he was the man of the house.

And you’re going to tell me we can’t ride 90 m to get him home? Bones was quiet for a long moment. Then he shook his head. Not in disagreement, in something else. Respect, maybe, or resignation, or both. When do we ride? Gunner looked at the window. The snow was still falling, but lighter now. The wind had dropped. First light.

At 4 in the morning, Gunner walked through the clubhouse and started waking people up. Not all of them, the ones he trusted most, the ones who could ride in conditions that would kill most men on two wheels. Colt, Ace, Duke, Bones, Wrench, Diesel, Hawk, 12 others. He stood in the middle of the room, voice low so he wouldn’t wake the family.

Listen up. That woman’s got a mother in Pine Ridge who doesn’t know she has a granddaughter. She’s got a boy who just lost his father and walked through a blizzard because he thinks he’s the man of the house. She’s got a 6-day old baby who almost died tonight on our doorstep. He paused, looked at every face in the room. We’re taking them home 90 miles.

Roads are going to be bad. I’m not ordering anyone. This is volunteer only. Nobody spoke for about 3 seconds. Then Colt stood up. I’m in Ace in Duke in Bones. You already know. Wrench, Diesel, Hawk, every single one of them. 15 men on their feet, ready. Gunner felt something tighten in his chest. He’d led this chapter for 12 years.

He’d seen them fight. He’d seen them bleed. He’d seen them do things that the world judged them for and things the world would never know about. But this right now, this was the best of them. “Saddle up,” he said. “We ride at sunrise.” Ethan woke up first. The gray light of dawn was filtering through the clubhouse windows.

The fire had burned down to embers. Lily was asleep on his mother’s chest, warm and pink and perfect. Ethan sat up, rubbed his eyes, and looked around. Through the window, he saw them. Men in leather jackets, breath steaming in the cold air, loading saddle bags onto motorcycles. Thermoses, blankets, a first aid kit, a box of baby formula, extra fuel cans strapped to a support truck that someone had pulled around from behind the building.

Ethan got up quietly, padded to the window in his socked feet, and pressed his face against the glass. Scunner was out there checking the bikes one by one. Colt was running the truck engine to warm it up. Bones was packing medical supplies into a bag. They were preparing for something. Something big. Ethan didn’t know what it was yet, but he watched them.

And for the first time since his father died, he felt something he’d almost forgotten. Safe. He pressed his small hand against the cold glass and whispered, “Dad, are you seeing this?” The wind outside had stopped. The snow had stopped. And the first light of morning was breaking through the clouds, turning the ice on the motorcycles into something that looked like it was made of gold.

Gunner looked up from the bikes and saw the boy watching from the window. Their eyes met through the glass. Gunner gave him a single nod. Ethan nodded back. And somewhere inside that boy, something shifted. Something that had been broken for eight months began very slowly to mend. Sarah woke to the sound of engines. Not one, not two, a wall of sound that vibrated through the floorboards and rattled the windows in their frames.

She sat up fast and the pain in her side hit her like a fist. She gasped, pressed her hand against the bandage bones had taped over her incision, and looked around. Ethan was already standing at the window. He turned to her and his face was something she hadn’t seen in 8 months. Bright, alive. Mom, they’re all outside.

All of them on their motorcycles. Sarah pulled Lily close and got to her feet. Every muscle screamed. She shuffled to the window and looked out, and what she saw made her breath catch in her throat. 15 Harley-Davidsons lined up in a row, engines running, exhaust curling into the frozen morning air. The bikers sat on their machines in full leather, helmets on, saddle bags packed.

Behind them, a black support truck idled with its headlights cutting through the early gray. The snow had stopped, but the world was buried. the road, the parking lot, the rooftops, everything was white and still and impossibly cold. Gunner stood by his bike at the front of the line.

He saw her at the window and walked toward the door. When he came inside, cold air rushed in with him. He pulled off his gloves and looked at Sarah. “Morning. What’s happening?” she asked. “We’re taking you to Pine Ridge.” Sarah stared at him. “What?” Your mother, Donna, Pine Ridge, 90 mi north. He said it like he was telling her the weather.

We’ve got the truck heated up for you and the kids. Bones is riding with you in the back. We loaded formula, blankets, water, food, and a medical kit. We’ll have you there by evening. Sarah shook her head. No, no, you can’t do that. It’s 90 miles. The roads are bad. I know. We’ll handle it. You don’t even know us. I know enough.

Gunner, I can’t ask you to. You’re not asking. He held her gaze, steady, unblinking. I’m telling you, we’re taking you home. Sarah’s mouth opened, but nothing came out. She looked past him at the line of bikes outside, the men sitting on them in the freezing cold, waiting, waiting for her.

For Ethan, for a 6-day old baby they’d met 12 hours ago. Why? She whispered. Gunner was quiet for a moment. Then he said, “Because your boy knocked on our door last night and asked for help. And where I come from, when a child asks you for help, you don’t say no. You don’t say maybe.” You say yes and then you move heaven and earth to make it happen.

Sarah felt the tears come. She didn’t fight them this time. Ethan was already pulling on his boots. Mom, let’s go. Let’s go see grandma. She laughed through the tears. That impossible, beautiful sound of a mother breaking and healing at the same time. Okay, baby. Okay. Gunner nodded once. Trucks warm. Let’s move.

They loaded up fast. Bones climbed into the back of the truck with Sarah, Lily, and Ethan. He had his field kit open, a thermos of warm formula, and three extra blankets. The truck cab was heated, and Wrench was driving, his massive hands steady on the wheel. Ethan pressed his face against the rear window of the cab, watching the bikers mount their machines behind them.

One by one, engines roared to life. The sound built like a wave, growing louder, deeper until it became something more than noise. It became a pulse, a heartbeat. Mom, Ethan breed, it’s like an army. Sarah put her arm around him. It is, baby. Gunner kicked his bike to life, rolled to the front of the convoy, and raised his left fist. The signal.

Every biker behind him revved once in unison. A single thunderclap that echoed off the mountains. Then he dropped his hand and rolled forward. The convoy moved out. 15 Harley’s, one truck, one mother, one baby, one boy. 90 miles of frozen mountain road between them and the only family they had left.

And the Hell’s Angels of Cedar Hollow rode like they’d been born for exactly this moment. The first 10 miles were slow. The road was a sheet of white and the bike struggled for traction on the packed snow. Colt’s rear wheel slid out on a curve and he caught it with a boot on the asphalt, grinding his heel to stay upright.

Ace hit a patch of black ice and fishtailed hard, but he corrected without slowing, jaw clenched, eyes locked on the road. Inside the truck, Ethan watched everything. He kept up a running commentary that nobody asked for, but nobody wanted to stop. That one almost fell, but he didn’t. He’s good. Mom, did you see that? He used his foot like a kickstand. Dad would have loved this.

Dad loved motorcycles. He always said he was going to get one when he came home. A Harley, a black one. Sarah listened and every word was a knife and a gift at the same time. The way Ethan talked about Jake, present tense, then past tense, then present again, like he couldn’t decide which world his father belonged to.

That was grief at 7 years old. Not a straight line, a maze. And her boy was walking it every single day without a map. Bones noticed Sarah staring at nothing. Her hand frozen on Lily’s back. She okay? Sarah blinked. Yeah. Yeah. She’s warm, breathing good. I wasn’t asking about the baby. I was asking about you. She looked at him.

His face was serious but kind. I’m fine. Your stitches are holding, but you’re running on adrenaline. When that drops, it’s going to hit you hard. I need you to eat something. I’m not hungry. I didn’t ask if you were hungry. He handed her a granola bar and a bottle of water. Eat. Your baby needs you functioning.

She took them, ate mechanically without tasting. Then she said, “You’re very bossy for a medic.” Bones almost smiled. You should have seen me in Fallujah. I once made a sergeant eat a protein bar while he was getting his legs stitched. He tried to outrank me. Didn’t work. Sarah let out a small laugh. It surprised her.

She hadn’t laughed, really laughed, in months. Thank you for last night for Lily if you hadn’t been there. But I was. Bones looked at her straight. That’s the thing about this life, Sarah. People think the club is about patches and bikes and looking tough. And yeah, some of it is. But the real thing, the thing nobody sees is that when something happens, we’re there. We show up.

That’s what family means. She didn’t respond. She just held Lily a little tighter and watched the mountains roll past through the truck’s rear window. 30 mi in, the convoy stopped. Wrench hit the brakes and the truck skidded slightly before coming to rest. Ahead, the road was gone. Not blocked, gone. A massive avalanche of rock, ice, and broken timber had swept across the highway, burying it under a wall of debris that stretched from the cliff face on one side to the drop off on the other.

Gunner killed his engine and dismounted. He walked to the edge of the debris field and stood there, hands on his hips, staring at it. Diesel pulled up beside him, whistled low. “That ain’t a rock slide, Pres. That’s the whole damn mountain. I can see that nearest detour is 40 mi back and adds another 60 to the route. We’d be looking at nightfall.

Maybe later.” Gunner didn’t respond. He was calculating. 40 m back meant 4 hours wasted. 60 extra meant five more on bad roads after dark. The baby needed to be indoors. Sarah needed a doctor. And the temperature was going to drop below zero by sunset. No detour, he said. Diesel stared at him.

Press, you can’t ride through a rock slide. We’re not riding through it. We’re moving it. That’s 30 tons of rock. Then we better start now. Gunner turned to the convoy and raised his voice. Not a shout. He never shouted. He just spoke and men listened. We’ve got a mother and two kids in that truck who need to get home. The road says no.

I say we change the road’s mind. Gloves on. Let’s work. Nobody hesitated. Not for a second. 15 men dismounted, pulled on work gloves, and walked into that wall of debris like they were walking into a bar fight they intended to win. They hauled boulders with their bare hands. Colt and Ace worked together on a slab of rock that must have weighed 300 lb, straining, grunting, feet slipping on ice until they got it to the edge of the road and over the side.

Diesel used a chain from his saddle bag to lasso a fallen tree trunk and hooked it to the truck’s trailer hitch. Wrench gunned the engine and dragged it clear. Duke found a gap in the debris and started digging with a tire iron, clearing loose rock and gravel, widening the path inch by inch. Hawk worked beside him, his jacket torn at the shoulder, his knuckles split and bleeding, and he didn’t stop.

Ethan watched from the truck window. He pressed his hand against the glass and said, “Mom, they’re digging through the mountain.” Sarah watched them. These men she’d been afraid of 12 hours ago, tearing a road open with their hands for her children. She put her hand over her mouth and couldn’t speak.

An hour passed two. The cold was brutal. Ace’s hands were so numb he couldn’t grip anymore. So, he switched to kicking rocks loose with his boots. Diesel’s nose was bleeding from the cold, and he wiped it on his sleeve without breaking stride. Colt’s back seized up, and he bent over, cursing, then straightened and went right back to work.

Gunner worked in the center of it all. He didn’t delegate. He didn’t stand back and supervise. He lifted. He hauled. He bled alongside every one of his men. His gloves shredded through in the first hour. And after that, it was bare skin on frozen rock. and he didn’t flinch. Bones came out of the truck periodically to check hands for frostbite.

He pulled Ace aside at one point. Your fingers are white. You need to warm up. Ace shook his head. I’ll warm up when the road’s clear. Ace, you’re going to lose fingers. Then I’ll learn to ride with 8. Move. Bones looked at Gunner, who had heard the exchange. Gunner met his eyes and gave a small shake of his head. let him work.

3 hours in, something happened that changed everything. A pickup truck appeared from the other direction. A local rancher, an older man named Bill, had been trying to get through from the Pine Ridge side. He’d seen the rock slide and was about to turn back when he saw something impossible.

A line of bikers, leather jackets and all, hauling rocks off the highway with their hands. He pulled over, got out, walked up to Gunner, who was dragging a chunk of concrete off the road. The hell are you boys doing? Gunner didn’t stop working, clearing the road. I can see that. Why? Got a family in that truck.

Mother, newborn baby, 7-year-old kid. They need to get to Pine Ridge. Bill looked at the truck, looked back at the bikers. He was the kind of man who’d been raised to avoid guys like this. Cross the street, lock the doors, don’t make eye contact. He walked back to his pickup, opened the bed, and pulled out a shovel and a pickaxe.

“Well,” he said, walking back. “You boys are doing it wrong. Let me show you how we move rock in this county.” Gunner looked at him. A slow grin spread across his face. “Yes, sir.” They worked together, the rancher and the bikers. And within 40 minutes, the gap was wide enough for the truck.

Bill stood back, wiping his forehead, and watched the convoy prepare to roll through. “Where you boys from?” he asked Gunner. “Cedar Hollow, Hell’s Angels.” Bill blinked, looked at the patches, looked at the men with bleeding hands and torn jackets, looked at the truck with the young mother and children inside. Well, he said slowly, “I guess I’ve been wrong about a few things.

” Gunner shook his hand. “You and the rest of the world, sir.” The convoy pushed through the gap. The road beyond was rough, but passable. They rode on. 50 mi in. 60. The sun was past its peak and dropping toward the mountains. Inside the truck, Lily slept against Sarah’s chest, warm and steady. Ethan had fallen asleep, too.

His head against the window, his breath fogging the glass in slow, even rhythms. Sarah was awake. She couldn’t sleep. She watched the bikers through the window, these men riding in formation around the truck like a shield. And she thought about Jake. She thought about the last thing he’d said to her before his final deployment. If anything happens to me, you take those kids and you go home to your mama.

Promise me, Sarah. she’d promised. And then she’d spent eight months breaking that promise because she was too proud, too scared, too stubborn to admit she couldn’t do it alone. It took a blizzard in a broken down car and a 7-year-old’s bravery to finally make her keep her word.

“I’m sorry, Jake,” she whispered to the window. “I’m sorry it took so long.” At the 70 m mark, the convoy stopped for fuel at a crossroad station. The gas station was small, just two pumps, and a convenience store with a blinking open sign. The attendant, a teenager, came out and froze when he saw 15 Harley-Davidsons pulling in. His hand went to his pocket, probably his phone, probably ready to call someone.

Then the truck door opened and Ethan jumped out, stretching his arms above his head. “Mom, can I get a snack, please?” The teenager stared, looked at the boy, looked at the bikers, looked at Sarah climbing out carefully with a newborn. Duke walked up to the pump and started fueling his bike. He nodded at the kid. Afternoon.

Are you Is everything okay? Better than okay. Duke jerked his thumb toward the truck. We’re taking that family home. The teenager looked at Sarah, who smiled at him. looked at Ethan, who was already inside picking out chips. Looked at Gunner, who was fueling up at the next pump, face weathered, eyes tired, hands wrapped in rags that were spotted with blood.

“Can I can I help?” the teenager asked. Gunner looked at him. “You got coffee in there?” “Yeah, fresh pot. Then you’ve already helped.” The teenager went inside and came back with a tray of coffee cups. He handed them out to every biker one by one. And when he got to Gunner, he said, “This one’s on the house. All of them.

” Gunner studied the kid’s face. 18, maybe 19. Trying to do something good and not sure how. Gunner took the cup. “Thank you, son. Thank you,” that the teenager said, “for whatever you’re doing out there.” When the convoy pulled out, the teenager stood at the edge of the parking lot and watched them go. He’d remember this for the rest of his life.

And 20 years later, he’d tell his own children about the day 15 Hell’s Angels stopped for gas on their way to bring a stranger home. And how he gave them coffee, and how the biggest one had bloody hands and the kindest eyes he’d ever seen. 80 miles. The road climbed, then dropped. They were close now. Sarah could feel it.

That pull in her chest. The one she’d been ignoring for eight months. The one that said, “Go home. Go home. Go home.” Bones checked Lily one final time. She’s perfect, Sarah. Strong vitals, good color. This kid’s a fighter. She gets that from her dad. Bones nodded. Yeah, she does. Ethan was awake now, face pressed against the window again.

Mom, I can see a town. Is that it? Is that Pine Ridge? Sarah leaned forward. Below them, in the valley, a small town glowed in the late afternoon light. She recognized the church steeple, the water tower, the elementary school where she’d learned to ride a bike in the parking lot on summer evenings while her mother watched from a lawn chair. “That’s it, baby.

” Her voice broke completely. “That’s home.” Gunner’s voice crackled over the truck’s CB radio. Wrench picked it up. Press says we’re 10 minutes out. He wants to know the address. Sarah wiped her eyes. 417 Elm Street. Yellow house. White shutters. There’s a maple tree in the front yard that my dad planted when I was born. Wrench related.

The convoy tightened formation. Bikes pulling closer together. Engines dropping to a low steady rumble. Not aggressive, not loud, respectful, like a procession, like an escort, like men who understood that what they were delivering wasn’t just a family. It was a promise, a dead soldier’s last wish, a mother’s prayer, a little boy’s hope, and they were going to deliver it right to the front door.

The convoy rolled into Pine Ridge at 4:47 in the afternoon and every single person on Main Street stopped what they were doing and stared. 15 Harley’s rolled down Main Street at walking speed and Pine Ridge held its breath. A woman outside the pharmacy grabbed her husband’s arm. A man loading groceries into his truck stopped with a bag in midair, mouth open.

Two kids on the sidewalk pointed and whispered. The barber stepped out of his shop with scissors still in his hand. Nobody knew what to make of it. 15 Hell’s Angels in full leather, patches blazing, riding in tight formation through a town that had never seen more than two motorcycles at a time. And in the middle of them, a black truck with a young woman visible through the window, holding a baby, a small boy’s face pressed against the glass beside her.

Gunner kept his speed low, steady. He wasn’t here to make a statement. He was here to finish what he started. Wrench’s voice came through the CB. Pres. Elm Streets. The next left. Copy. The convoy turned. The engines echoed between the houses. A deep rumble that shook mailboxes and rattled storm doors.

Dogs barked. Curtains pulled back. An old man on his porch stood up from his rocking chair and took off his hat, watching like he was seeing a parade he didn’t understand but knew was important. And then Wrench said, “There it is. 417 yellow house.” Gunner saw it. Small, well-kept, white shutters just like Sarah said.

A maple tree in the front yard, bare and skeletal in the winter, but standing tall. A porch light was on even though it was still afternoon. Like someone inside always kept it burning. Like someone was always waiting. He raised his fist. The convoy stopped. One by one, engines died. The silence that followed was enormous.

It pressed against the cold air like a held breath. Gunner dismounted, took off his helmet. His hair was matted with sweat, his face raw from the wind, his hands still wrapped in blood spotted rags. He walked to the truck and opened the door. Ethan was already unbuckled. The boy’s eyes were locked on the yellow house, and his whole body was vibrating with something too big for his small frame to contain.

“Is grandma in there?” he whispered. “Only one way to find out,” Gunner said. Ethan looked up at him. Then the boy did something nobody expected. He reached out and grabbed Gunner’s hand. Not his mother’s Gunner’s. And he held on tight. Gunner felt it like a bullet. That small hand in his massive ruined one.

He looked down at Ethan and for a moment the president of the Hell’s Angels Cedar Hollow chapter couldn’t speak. He squeezed the boy’s hand. Let’s go, soldier. They walked up the path together. Ethan and Gunner. Behind them, Sarah climbed out of the truck with Bones’s help. Lily cradled against her chest.

The bikers stayed by their machines, watching. Nobody moved. Nobody spoke. Ethan climbed the porch steps. His boots were still damp. His jacket was still too big. His brown hair stuck up at odd angles from sleeping against the truck window. He stood at the front door of his grandmother’s house and he knocked the same knock. Small, desperate, full of everything a seven-year-old doesn’t know how to say with words.

Footsteps inside, slow, the sound of a lock turning, the door open. Donna Mitchell stood in the doorway. 62 years old, silver blonde hair pulled back, reading glasses pushed up on her forehead. She was wearing an apron dusted with flour and her hands were white with it because she’d been baking the way she always baked when she was worried.

The way she’d been baking every day for 8 months because her daughter had stopped returning calls. And her grandson’s voice on the phone had gotten quieter each time, and she didn’t know why, and it was killing her. She looked down, saw Ethan. Her hand went to her chest. The flower left a white print over her heart. Ethan. Hi, Grandma.

She dropped to her knees right there in the doorway, knees hitting the hardwood, and she grabbed that boy and pulled him into her arms so hard that his feet left the ground. She held him like the world was ending, like he was the last solid thing left. Oh my god. Oh my god, baby. Oh my god. Ethan buried his face in her neck.

We came home, Grandma. Mom said we could come home. Donna was sobbing. The kind of sobbing that has no dignity and no restraint because it’s been building for 8 months across a thousand unanswered prayers. She rocked him. Flower handprints on his jacket, tears dropping into his hair. Then she looked up and she saw Sarah.

Her daughter was standing at the bottom of the porch steps, thin, pale, dark circles under her eyes, a bandage visible under her shirt, and in her arms, a baby, a tiny, bundled, sleeping baby that Donna had never seen, had never known about. Donna’s mouth opened. No sound came out. “Mama,” Sarah said, her voice cracked down the middle.

“This is Lily. She’s 6 days old. I should have called. I should have come sooner. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I just I didn’t know how to tell you. I didn’t know how to ask for. Donna was already down the steps. She crossed the distance in three strides and wrapped her arms around her daughter, around the baby, around everything she’d been missing.

And the sound she made wasn’t a word. It was a sound older than language. The sound a mother makes when her child comes back from somewhere she was afraid she’d never return from. They stood there, three generations, holding each other on the front walk of a yellow house on Elm Street while 15 Hell’s Angels stood at the curb and watched.

Colt turned his head away. His jaw was working. Duke was staring at the sky, blinking hard. Diesel had his hand over his mouth. Hawk was gripping his handlebars so tight his knuckles were white and his shoulders were shaking. Bones stood by the truck, arms folded, and let the tears roll down his face without wiping them.

He’d seen men die in the desert. He’d held soldiers while they bled out on dirt roads 10,000 m from home. But this this was the other side of that. This was what the dying ones were always talking about, the people they wanted to get back to. the door they wanted to walk through one more time and he was watching it happen and it broke him open in the best possible way.

Gunner stood at the gate, helmet under his arm. He didn’t cry, but his eyes were bright and his throat was tight. And when Donna finally lifted her head from her daughter’s shoulder and looked past them toward the street, Gunner had to take a breath before he could hold her gaze. Who? Donna’s voice was shattered.

Who are these men? Ethan pulled back from his grandmother and pointed at Gunnar. That’s Gunner, Grandma. He’s the president. He held Lily on his chest when she was too cold. He saved her. And those are his guys. They rode us all the way here, through the snow and everything. They moved a whole mountain to get us through. Donna stared at the bikers.

She saw the leather, the patches, the words, “Hell’s angels stitched across their backs.” She saw the blood on their hands, and the exhaustion on their faces, and the way they stood by their machines like they were ready to leave now that the job was done. “You brought my family home,” she said. Gunner nodded. “Yes, ma’am.

” “From where?” “Cedar Hollow, 90 mi south. They walked into our clubhouse last night in the middle of the blizzard. Your grandson knocked on our door and asked if they could stay the night. Donna put her hand over her mouth. She looked at Ethan, then at Sarah, then at the baby, then back at Gunnar. 90 miles, she repeated. You rode 90 m in this.

Yes, ma’am. Why? Gunner looked at the boy, looked at the baby, looked at the young mother who had walked through a blizzard six days after surgery because she’d made a promise to a dead man. Then he looked back at Donna. Because your son-in-law gave his life for this country, and the least we could do was make sure his family got home.

Donna broke. She walked straight to Gunner and put her arms around him. This 62year-old woman, four inches shorter than his shoulder, flower on her apron, tears on her face, hugged the president of the Hell’s Angels like he was her own son. Gunner didn’t move for a moment. His arms hung at his sides.

Then slowly, carefully, he put them around her and held on. “Thank you,” she whispered into his jacket. “Thank you for bringing them back to me. I thought I’d lost them. I thought I’d lost all of them. You didn’t lose them, ma’am. His voice was rough. They were just taking the long way home. She pulled back, wiped her eyes, and looked at the row of bikers.

15 men, frozen, exhausted, bleeding, and not one of them had asked for anything in return. “Every single one of you,” she said, her voice rising, steadying. “Every single one of you is coming inside my house right now. I have stew on the stove and bread in the oven and I will not hear one word of argument. You hear me? Rex? Gunner started to shake his head.

Ma’am, we don’t want to impose. Impose? Donna’s eyes flashed. You just brought my daughter and my grandchildren 90 m through a blizzard. You saved my granddaughter’s life. You moved rocks with your bare hands. She pointed at the front door. Get in that house, all of you, now. Duke grinned. Press, I think she outranks you. A ripple of laughter went through the group. Tired laughter. The best kind.

The kind that comes after you’ve been through hell and someone offers you a seat at the table. Gunner looked at Donna. Then he looked at his men. Then he smiled. The kind of smile that takes years off a man’s face. You heard the lady, “Move out.” One by one, the Hell’s Angels walked up the front path of 417 Elm Street and into Donna Mitchell’s house.

Boots on hardwood, leather in a living room filled with family photos and knitted afghans, and the smell of beef stew and fresh bread. They filled the small space like an army filling a church, big and awkward and out of place, and exactly where they were supposed to be. Donna moved through them like a general. She took jackets. She poured coffee.

She pointed at chairs and said, “Sit.” And they sat. She saw Diesel’s cracked, bleeding hands and disappeared into the bathroom, coming back with peroxide and bandages. “Give me those hands,” she ordered. Diesel looked at Gunnar. Gunner shrugged. Diesel held out his hands. Donna cleaned them carefully, gently, wrapping each finger with the kind of attention that only a mother knows how to give.

Diesel watched her work and his lower lip trembled once before he clamped down on it. “You remind me of my mom,” he said quietly. Donna looked up at him. “Where’s your mother, honey?” “Tan, haven’t seen her in 4 years.” “You call her tonight. You hear me? You call her tonight and you tell her you love her.” “Yes, ma’am.

” She moved to Ace next, then Hawk. She cleaned every pair of bloody hands in that house. And by the time she was done, the roll of gauze was empty, and there wasn’t a dry eye in the room, though every man there would deny it later. Ethan had claimed the center of the living room. He sat on the floor with Lily in his lap, supported by pillows, and he was introducing her to every biker who walked past.

This is my sister, Lily. She’s 6 days old. She almost died last night, but Gunner saved her. She likes being warm. She doesn’t really do anything yet, but mom says she’ll be fun later. The bikers took turns crouching down to meet her. Duke let Lily grab his finger and held still for three full minutes, afraid to move, afraid to breathe, like he was holding a grenade with the pin pulled.

Hawk made a face at her, and she stared at him with wide, dark eyes that seemed to look straight through him. “Kids got her mama’s eyes,” Hawk said. Sarah was sitting at the kitchen table with Donna. They were holding hands across the table. Donna hadn’t let go of her daughter since they’d come inside. She kept touching Sarah’s face, her hair, her shoulder, like she was checking to make sure she was real.

“Why didn’t you call me?” Donna asked. “8 months. Why didn’t you tell me about the baby? Why didn’t you tell me how bad things were?” Sarah’s eyes dropped to the table. Because Jake was the strong one, mama. He was always the strong one. And when he died, I thought I had to be strong, too.

I thought asking for help meant I was failing. Donna shook her head. Coming home isn’t failing, Sarah. Coming home is the bravest thing you could have done. I know that now. Sarah looked toward the living room where Ethan was laughing as Diesel made silly faces at Lily. Ethan carried the diaper bag through the blizzard. Mama 2 miles. He never dropped it.

He told me he was the man of the house. He’s 7 years old and he thinks he has to carry everything because his father’s gone. Donna’s face twisted with pain. That boy. He knocked on the door of a biker clubhouse because I was too weak to stand up. He saved us, mama. A seven-year-old saved his mother and his baby sister because nobody else was there to do it. Somebody was there.

Donna looked toward the living room, toward Gunner, who was standing by the window with a cup of coffee, watching the street. They were there. Sarah followed her gaze. Yeah, they were. Gunner felt their eyes on him. He turned from the window and caught Sarah looking at him. She mouthed two words. Thank you. He nodded once.

Then he turned back to the window and took a long sip of coffee. And if his hand shook slightly, nobody mentioned it. Outside, the town was buzzing. Word had spread through Pine Ridge like a brush fire. The Hell’s Angels brought a family home, rode 90 m in the dead of winter, saved a newborn baby, cleared a rock slide with their bare hands.

The story grew with every telling, the way stories do in small towns. But this time, the story didn’t need to grow. The truth was already bigger than anything anyone could have invented. Sheriff Tom Miller drove by the house twice before he finally parked. He sat in his cruiser for a full minute watching the row of Harley’s lined up along the curb like chrome soldiers standing at attention.

Then he got out, adjusted his belt, and walked up the front path. Donna opened the door before he knocked. Tom. Donna. He looked past her into the house, saw the bikers, saw the patches. His hand moved instinctively toward his hip, then stopped. “Everything all right here? Everything is perfect, Tom. My daughter’s home.

My grandchildren are home, and these men are the reason why.” The sheriff looked at Gunner, who had stepped into the hallway. Their eyes met. Two men on opposite sides of a line that had been drawn long before either of them was born. Sheriff Gunner said, “You the one in charge of this group?” “I am. You rode here from Cedar Hollow.

” “We did.” The sheriff studied him for a long moment. Then he looked at Ethan, who had appeared in the living room doorway, holding Lily with the careful concentration of a boy who understood that some things are more important than being afraid. That’s your boy? The sheriff asked Sarah. Yes, sir. He okay? He is now.

The sheriff looked at Gunnar one more time. Then he reached out his hand. Gunner looked at it. Then he took it. They shook once firm. Drive safe going home, the sheriff said. And thank you. He turned and walked back to his cruiser. He sat inside for a moment, staring at the steering wheel. Then he picked up his radio.

Dispatch, this is Miller. Go ahead, Sheriff. You can cancel that alert about a biker convoy heading into town. They’re friendlies. He hung up the radio, looked at the yellow house one more time, shook his head slowly. I’ll be damned, he muttered, and he drove away. Inside the house, Donna was ladling stew into every bowl she owned.

She’d run out of bowls and switched to mugs. And when those ran out, she used measuring cups. Nobody cared. They ate standing up, sitting on the floor, leaning against walls. They ate like men who had earned every bite. And Donna kept the pot going, adding water and vegetables and whatever she could find, stretching the stew the way mothers have always stretched meals when the table is suddenly full of people who need feeding.

Ethan sat on the floor between Duke and Diesel, eating bread and stew and talking non-stop. He told them about his school, about his friend Marcus who had a dog named Rocket, about how his dad used to build model airplanes with him on Saturday mornings, about how he was going to teach Lily to throw a football when she was big enough. Duke listened to every word.

And somewhere in the middle of that little boy’s endless, beautiful monologue about his dead father’s model airplanes, Duke made a decision. He was going to call his daughter in Reno tomorrow. He was going to stop making excuses. He was going to say, “I’m sorry and I love you and I’m coming home because life was too short and too fragile and too full of blizzards to waste another day being afraid.

” He didn’t tell anyone about this decision. He didn’t need to. Some things you just carry with you and act on later. And the acting is what matters. Gunner finished his stew, set down his mug, and walked to the window again. The sun was dropping fast. Long shadows stretched across Elm Street. His men were tired.

The road home was 90 mi of cold and dark. It was time to go. He found Sarah in the kitchen. She was washing dishes, moving slowly, favoring her left side. Donna was beside her, drying. Sarah, we need to head out. She turned, set down the dish, dried her hands on a towel. Then she walked up to him, and she did something that caught him completely offguard.

She put her arms around him and held on. Gunner stood still. His arms hung at his sides for a moment, the same way they had with Donna, then he wrapped them around her lightly, carefully. The way you hold something you’re afraid to break. I don’t have anything to give you, she said into his jacket. I don’t have money. I don’t have anything.

I didn’t do this for money. I know. That’s why I don’t know what to give you. Gunner pulled back and looked at her. You already gave it, Sarah. You gave us a reason to be who we always wanted to be, and nobody ever let us. She wiped her eyes, nodded. Then she called for Ethan. The boy came running. He skidded to a stop in front of Gunner and looked up at him with those serious brown eyes.

Then he reached into his pocket and pulled something out. It was a small green plastic army man, scuffed, worn, one arm slightly bent from years of play. The paint was rubbed off in places down to bare plastic. “This was my dad’s,” Ethan said. “He had it since he was my age. He carried it everywhere, even to Afghanistan.

It was in his pocket when the boy stopped, swallowed. When they sent his stuff home, “Mom gave it to me.” Gunner crouched down so he was eye level with the boy. “I want you to have it,” Ethan said. “For good luck, so you get home safe.” Gunner looked at the small figure in the boy’s outstretched hand.

a toy soldier carried by a real soldier who never came home. Given by that soldier’s son to a man the world called an outlaw. He took it, held it in his palm, felt the weight of it, which was almost nothing and everything at the same time. I’ll carry it every mile, soldier. His voice was barely above a whisper. You have my word. Ethan nodded.

Then he stepped forward and wrapped his arms around Gunner’s neck. The boy held on tight and Gunner held him back, one hand on the boy’s head and he closed his eyes. And in that moment, every wrong thing anyone had ever said about him didn’t matter. Every arrest, every headline, every cross street and locked door, none of it mattered because a 7-year-old boy who had lost his father trusted him.

And that was worth more than the world’s approval would ever be. Gunner set the boy down, stood up, tucked the army man into his vest pocket right over his heart. He looked at Sarah, at Donna, at Lily asleep in her grandmother’s arms, at Ethan standing tall in his two big jacket. You take care of each other, he said. You take care of yourself, Sarah replied.

He turned and walked out the front door. His men were already by their bikes, helmets on, ready. The cold hit him like a wall, but he barely felt it. He swung his leg over his Harley, settled into the seat, and gripped the handlebars. Donna came out onto the porch with the baby. Sarah stood beside her. Ethan stood at the railing, one hand raised.

Gunner looked at them, burned the image into his memory. The yellow house, the porch light, the family. He kicked the engine to life. One by one, the others followed. 15 Harleys roared awake on that quiet street, and this time the sound wasn’t thunder. It was a promise kept. Ethan waved. Gunner nodded, and the Hell’s Angels of Cedar Hollow pulled away from 417 Elm Street, headlights blazing through the gathering dark, chrome catching the last light of the dying sun, and they rode.

The convoy hit darkness 20 minutes out of Pine Ridge. Not twilight, not dusk, full dark, the kind that swallows headlights and makes the road disappear 3 seconds ahead of your front tire. The temperature had dropped 15° since they left Elm Street. And the cold came through leather like it wasn’t there. Gunner Road Point.

His hands achd inside his gloves, the torn skin on his knuckles burning against the frozen leather. The army man in his vest pocket pressed against his chest with every bump in the road. And he could feel it there, small and solid, like a second heartbeat. Nobody talked. The CB was silent.

Just engines in wind in the hiss of tires on frozen asphalt. 15 men riding through the dark on a road they’d already conquered once today. heading back the way they came with nothing in their saddle bags but empty thermoses and bloody rags. Colt pulled up beside Gunner at a straightaway and matched his speed.

He didn’t say anything for a mile. Then his voice came through the cold, barely audible over the engines. Press. Yeah. You good? Gunner didn’t answer right away. He was thinking about the boy’s face. The way Ethan had looked at him when he handed over the army man. The trust in those brown eyes, total, complete.

The kind of trust that a child gives you once and you either earn or destroy and there is no middle ground. Yeah, he said finally. I’m good. That kid got to you. That kid got to all of us. Colt nodded, fell back into formation. They rode on. 40 mi from Cedar Hollow, Ace’s bike started coughing. The engine sputtered, caught, sputtered again.

He’d been running low on fuel since the gas station stopped, and the cold was eating into what was left. He signaled with his left hand, dropping back, and Diesel moved in beside him. “How bad?” Diesel asked. “Bad? I’ve got maybe 5 miles. There’s nothing for 20.” Ace looked at his gauge, then at the road, then at Diesel. I’ll ride till she dies and then I’ll figure it out. Like hell you will.

Diesel reached into a saddle bag one-handed, still riding, and pulled out a length of rubber hose. Next wide spot, we siphon. I’ve got enough to split. D, that’ll leave you short. Then we’ll both limp home. Better than one of us not making it. Ace stared at him. Diesel stared back. Neither of them slowed down. You’re an idiot, Ace said.

You’re welcome. They found a pulloff 3 mi later. The convoy stopped. Diesel siphoned a gallon and a half from his tank into Aces, working by the light of Hawk’s headlamp, hands shaking from the cold. Fuel splashed on his boots and the fumes burned his eyes, but he got it done in 4 minutes flat. Gunner watched from his bike.

He didn’t offer to help because Diesel didn’t need help. He just needed someone to witness what brotherhood looked like at 11:00 at night on a frozen highway with no audience but the men who lived it. We good? Gunner called. We’re good, Pres. Then let’s move. Engines fired. The convoy rolled. 50 mi 60. The mountains closed in around them and the road narrowed to a two-lane ribbon of black cutting through white.

Hawk’s headlight flickered once, twice, then held. Wrench’s truck hit a pothole so deep the chassis bottomed out, and the sound was like a gunshot in the dark. Every biker’s head turned. Wrench gave a thumbs up through the window. They kept going. It was around the 65m mark that Duke dropped back to the rear of the convoy and keyed his CB.

Press, you copy? Go ahead, Duke. I need to say something, then say it. Duke was quiet for a moment, just the sound of his engine. Then he said, I’m calling my daughter tomorrow. Gunner didn’t respond. I haven’t seen her in 2 years, president. 2 years. She turned 8 last month and I wasn’t there. Her mother sends me pictures sometimes and I look at them and I put my phone away and I tell myself, “Next week.

Always next week.” And then that boy today. Duke’s voice cracked. He cleared his throat hard. That boy carried a diaper bag through a blizzard because his dad told him to take care of his family. His dad’s dead, Gunnar. His dad’s dead and he’s still doing what his father asked. And I’m alive. I’m alive and I can’t even pick up the phone.

The CB was silent. Every man in the convoy had heard it. Nobody interrupted. I’m calling her tomorrow, Duke said again. And I’m going to Reno. I don’t care what her mother says. I don’t care if she slams the door. I’m going. Gunner let the silence sit for another moment. Then he keyed his mic. About damn time, brother. Duke laughed.

It was wet and broken and real. Yeah. Yeah, it is. Colt’s voice came over the CB next. Duke, when you go to Reno, you’re not going alone. I’ll ride with you. Then Hawk. I’m in too. Then Diesel. Count me. Then Bones. Same. Duke couldn’t talk anymore. He just rode and the tears froze on his face before they reached his jaw. And he let them.

Gunner listened to his brothers volunteering one by one to ride across state lines to help a man they’d fight and die for knock on a door he was afraid to knock on alone. and he thought about what Bones had said to Sarah in the truck that morning. The real thing, the thing nobody sees, is that when something happens, we show up.

That’s what family means. He’d never heard it said better. They crossed the county line at midnight. The sign read Cedar Hollow, population 2,847. And Gunner felt something in his chest release. Not relief exactly, something deeper. The feeling of having gone out into the world and done something that mattered and coming back changed by it.

The convoy crested the final ridge, and below them the town lay quiet and dark, a few street lights, the gas station, the blinking neon of the iron wolves den. And standing outside the den, arms crossed, coat pulled tight against the cold, was Maria. She’d been waiting. Of course she’d been waiting.

Maria Santos had run the diner next to the clubhouse for 19 years. She’d fed these men through hangovers and heartbreaks and holidays. She’d bandaged their hands after fights, yelled at them for tracking mud on her floors, and kept a pot of coffee going every night until the last bike pulled in. She was not a member of the Hell’s Angels.

She was something more important. She was the person who stayed. The convoy rolled into the parking lot. Engines died one by one. The silence that followed was heavy with exhaustion and something else that none of them would name out loud, but all of them felt. Maria walked up to Gunner as he dismounted.

She looked at his face, at his hands, at the rags wrapped around his knuckles, dark with dried blood. She looked at the line of men behind him getting off their bikes like they were climbing out of trenches. 18 hours, she said. You’ve been gone 18 hours. Sounds about right. I called you six times. Phone died around hour 10.

I thought you were dead in a ditch somewhere. Not tonight. She stared at him. Her eyes were hard, the way they got when she was trying not to cry. Did you get them there? Gunner reached into his vest pocket and pulled out the green army man. He held it up so she could see it in the neon light.

Small, worn, one arm bent, paint rubbed to bare plastic. A 7-year-old boy gave me this, he said. It was his father’s. His father was a soldier. Carried it since he was a kid. Took it to Afghanistan. Died there. He looked at the figure. His boy gave it to me for good luck. Said he wanted me to get home safe.

Maria’s hand went to her mouth. Yeah, Maria, we got them there. She nodded, blinked hard, turned around, and walked into the diner without another word. She came back 90 seconds later with a tray of coffee cups and a plate of sandwiches she’d made 3 hours ago and kept warm in the oven because she knew. She always knew. The bikers ate standing in the parking lot, leaning against their bikes, too tired to go inside. Nobody said much.

They chewed and sipped and stared at the stars, which were out now, bright and cold and impossibly clear. Bones sat on the curb, eating a sandwich, and Gunner lowered himself down beside him. They sat in silence for a while. Two men who had served their country and then served their club and today had served a family they’d never met. Pres.

Bone said, “Yeah, that baby was in trouble. Real trouble. Another 30 minutes in that cold and we’d be having a different conversation right now. Gunner nodded slowly. He knew he’d known it when he took Lily against his chest and felt how cold she was. He’d felt death in that coldness. Not a metaphor, the actual thing.

The absence of warmth that comes right before the absence of everything else. But she made it, Gunner said, because you held her. Because we all held her, every one of us. From the moment that boy knocked on our door. Bones finished his sandwich, crumpled the wrapper. I’ve saved lives before in the field under fire, and every time it stayed with me, but different, clinical, like I was doing a job.

This one, he paused, this one felt like something else. What atonement maybe? I don’t know. like the universe gave us a chance to balance something out. Gunner thought about that for a long time. He thought about every wrong turn he’d taken, every bad decision, every night he’d spent wondering if the life he’d chosen was worth anything at all.

And then he thought about a 7-year-old boy standing in his doorway, shaking, brave, asking for help. “Maybe you’re right,” he said. “Maybe that’s exactly what it was.” They sat there a while longer. Then Gunner stood, groaned as his knees protested, and walked inside the clubhouse. The fire had gone out. The room was cold.

He knelt by the hearth, stacked kindling, and lit it. The flames caught slowly, then grew, filling the room with warmth and the smell of burning pine. He pulled up a chair and sat down. One by one, the others came in. Colt sat at the bar. Diesel took the couch. Hawk pulled a chair up to the fire.

Duke sat on the floor, back against the wall, legs stretched out. Ace, Wrench, and the rest found their spots. The places they always sat, the positions they’d earned over years of riding together. Nobody turned on music. Nobody reached for a bottle. They just sat. And the fire crackled. And the room filled with the kind of silence that isn’t empty.

The kind that’s full of everything you just went through settling into your bones like heat after cold. Diesel spoke first. You think they’re okay? The family? They’re home. Gunner said they’re okay. The boy, Ethan, Diesel shook his head. 7 years old, walked through a blizzard, knocked on our door, carried a diaper bag the whole way because his dead father told him he was the man of the house.

He stared at the fire. I wasn’t half that brave at 30. None of us were, Colt said quietly. His dad, Hawk leaned forward in his chair. Staff Sergeant IED in Kandahar, 29 years old, left behind a wife, a son, and a baby he never met. He rubbed his face. “Man, that’s heavy. That’s the cost,” Bone said from the corner.

That’s the cost of the freedom everybody takes for granted. A 29-year-old man in the dirt 10,000 mi from his family. And the people back home don’t even know his name. We know it, Gunner said. Jake Mitchell. Staff Sergeant Jake Mitchell, Third Infantry Division. We know his name. The room was quiet. And his son knows ours. Duke added.

Gunner reached into his pocket and took out the army man. He turned it over in his fingers, studying it in the fire light. The tiny rifle, the tiny helmet, the bent arm. He set it on the mantle next to the chapter’s founding photo. It looked small up there, but it belonged. That stays, he said. Nobody moves it. Nobody would dare press, Diesel said.

Gunner stared at the figure on the mantle. a toy soldier standing guard over a room full of men the world called outlaws. There was something about that image that felt right. Felt true, like the universe had a sense of humor and a sense of justice at the same time. I’ve been thinking, Gunner said. He didn’t turn from the mantle.

We’ve been a lot of things to a lot of people. Some of it earned, some of it not. But tonight, for one family, we were exactly what our name says. Angels. Hell’s Angels, Hawk corrected with a grin. Same thing, Gunner said, just with better bikes. Laughter. Real laughter. The kind that fills a room and pushes the dark back and reminds you that no matter what the world thinks of you, the people in this room know the truth.

Colt raise his coffee mug. to Jake Mitchell. Soldier, father, the reason we rode today. Every man in the room raised what they had. Coffee, water, an empty cup. It didn’t matter. To Jake Mitchell, they said together. The fire popped. Sparks spiraled upward. And in the silence that followed, Gunner could almost hear it. Not Marjgery’s voice like in the story he’d carry for the rest of his life, but a different voice, smaller, braver.

“Can we stay overnight, please? My baby sister is really cold,” he closed his eyes. “Yeah, kid,” he whispered. “You can stay.” The fire burned on. The men sat in its warmth, not sleeping, not talking, just being together, the way they’d always been, the way they always would be. Outside, the wind had stopped. The stars pressed close to the earth, and Cedar Hollow slept, not knowing that the men it feared had just done something that would change the way this town saw them forever.

But that was tomorrow’s story. Tonight, they rested. Tonight, the soldiers and the outlaws and the brothers and the angels sat by the fire and let the world spin without them for a few hours. They had earned that. They had earned it with frozen hands and split knuckles and 90 m of road and a promise made to a 7-year-old boy who had the courage to knock on a stranger’s door.

Gunner opened his eyes one more time, looked at the army man on the mantle, looked at his brothers around the fire. Nobody ever asks us why we ride, he said quietly. Colt looked up. What’s that, Pres? People ask what we ride, where we ride, how fast, how loud, but nobody ever asks why. So what’s the answer? Gunner leaned back in his chair.

The fire light caught the scars on his hands, the patches on his vest, the lines on his face that told a story no newspaper would ever print. Because the road’s full of people trying to get home. And sometimes they can’t make it alone. And when they can’t, we show up. That’s why we ride. That’s why we’ve always ridden. Nobody argued.

Nobody added anything. It didn’t need anything added. Duke stood up, stretched, and walked toward the back room. He stopped in the doorway. Hey, press. Yeah, I’m calling my daughter first thing in the morning. Gunner smiled. I know you are. Duke disappeared down the hall. One by one, the others followed, finding bunks, couches, floor space, settling in, letting the day go.

Gunner was the last one awake. He sat by the fire until the flames burned down to embers, and then he sat with the embers until they were just coals, glowing orange in the dark. He pulled out his phone, dead battery. He’d charge it in the morning. But there was something he wanted to do.

So he found a pen and a scrap of paper on the bar and he wrote two words, Jake Mitchell. He folded the paper and tucked it behind the army man on the mantle. A name, a monument so small that nobody would notice it unless they looked, but it was there and it would stay there. And every man who walked into this clubhouse would eventually ask about the little green soldier on the mantle.

And every man who asked would hear the story. And the story would keep Jake Mitchell alive in a way that metals and flags and folded letters never could. In the mouths of men who never knew him but honored him anyway. In a clubhouse that had seen a hundred stories but would remember this one longest.

Gunner touched the figure one last time. “Rest easy, Sergeant,” he said. “Your family’s home.” Then he turned off the light and walked down the hall to his room. He didn’t take off his boots. He didn’t take off his jacket. He lay down on the bed and closed his eyes and was asleep in 30 seconds. The way soldiers and bikers and men who have carried heavy things learned to sleep fast, deep, dreamless.

The iron wolves den was silent. The fire died to ash. The neon sign outside flickered and buzzed, casting red light through the windows in slow, steady pulses. And on the mantle, a small green army man stood guard over sleeping angels. Gunner woke to the sound of someone pounding on the clubhouse door. He was on his feet before his eyes were fully open.

Old habit, the kind that comes from years of expecting trouble at every knock. He pulled on his boots, walked down the hall, and opened the front door. Maria stood there holding a newspaper. Her face was doing something he’d never seen before. She was smiling and crying at the same time. “You need to see this,” she said.

She handed him the paper. “The Cedar Hollow Gazette, Morning Edition, front page.” The headline read, “Hell’s Angels ride 90 miles through Blizzard to bring stranded military family home.” Below it, a photo. Somebody in Pine Ridge had taken it from across the street. The shot showed the convoy parked outside Donna’s yellow house.

15 Harley’s lined up at the curb and on the porch, barely visible, but unmistakable, a small boy waving. Gunner stared at it. “Where’d they get this?” he asked. “It’s everywhere, Gunner. Not just the gazette. I’ve been getting calls since 5 in the morning. The AP picked it up. There’s a TV station in Denver that wants to talk to you.

A radio show in Dallas called The Diner asking for your number. Gunner folded the paper. No interviews. Gunner. No interviews, Maria. We didn’t do it for cameras. She studied his face, then she nodded slowly. I know you didn’t, but the world wants to know who you are. The people who matter already know. He turned and walked back inside and Maria watched him go with a kind of expression that lives somewhere between frustration and deep aching pride.

The clubhouse came alive slowly that morning. Men emerged from back rooms, from couches, from the floor where they dropped the night before. Bones was first to the coffee pot. Diesel was second. They didn’t talk. They just poured and drank and let the caffeine do its work. Then Colt walked in from outside holding his phone. “Press, you’re going to want to hear this.

If it’s a reporter, I already told Maria.” “It’s not a reporter,” Colt held up the phone. “It’s from the VFW post in Pine Ridge. The Veterans of Foreign Wars commander named Patterson.” He left a voicemail. Gunner looked at the phone. “Play it.” Colt hit speaker. The voice that came through was older, steady, military.

This message is for the president of the Hell’s Angels, Cedar Hollow chapter. My name is Colonel Frank Patterson, retired United States Army. I’m the commander of VFW Post 1,187 in Pineriidge. I heard what you and your men did for Staff Sergeant Mitchell’s family. I’ve been in this town 40 years, and I’ve never seen anything like it.

I’d like to invite you and your chapter to our Memorial Day ceremony this spring. We’d be honored to have you. You showed this community what service looks like when it doesn’t wear a uniform. God bless you, son, and God bless your brothers. The room was dead quiet. Diesel sat down his coffee mug. Did a colonel just call us brothers? Bones exhaled through his nose.

Yeah, D, he did. Gunner looked at the phone for a long moment, then at his men, then at the mantle where the green army man stood in the firelight. Colt, call him back. Tell him we’ll be there. You serious, Pres? We rode 90 m for Jake Mitchell’s family. We can ride 90 more to stand at his memorial. He paused. It’s what he would have wanted.

It’s what his boy would want. Nobody argued. Nobody ever argued when Gunner’s voice got that quiet, that certain. The morning passed. The news spread through Cedar Hollow the way news spreads in small towns. Fast, messy, and irreversible. By noon, the story had changed the texture of the town. Not loudly, not dramatically, in small ways that you’d only notice if you were paying attention.

The woman at the hardware store who had always crossed the street when bikers walked past stopped crossing. She stood at her counter when Diesel came in for duct tape and she said, “I read what you boys did. That was something.” Diesel didn’t know what to say. He’d never been thanked by a stranger for anything in his life. Just doing what needed doing, ma’am.

Well, she said, “The world could use more of that.” The barber gave Hawk a free haircut. wouldn’t take his money, just said, “This one’s on me, son.” And went back to sweeping. The gas station owner, a man named Phil, who had called the sheriff on the club twice in the last 5 years, walked into the Iron Wolves’s den at lunchtime, carrying two cases of beer.

He set them on the bar, looked at Gunner, and said, “For the road. Next time you boys need fuel, it’s on my tab.” Gunner shook his hand. Didn’t say much. didn’t need to. But the moment that hit hardest came at 3:00 in the afternoon when a delivery truck pulled up outside the clubhouse. The driver carried in a box. No return address, just a label that read for the Angels.

Gunner opened it at the bar. Inside was a folded American flag, crisp, perfect triangle fold, the kind that gets presented to a family when a soldier doesn’t come home. Under it was a letter handwritten. The handwriting was shaky. The letters formed slowly by hands that were old but steady enough.