The ledger sat on census officer James Hartley’s desk for 3 days before he opened it again. He’d counted plantations across five counties that season, recorded their acres, their livestock, their holdings, both living and material. But the numbers from Magnolia Springs Plantation kept pulling him back.

Not because they were wrong exactly. They balanced. Every column added up. Every figure matched its corresponding entry. That was precisely what disturbed him. Numbers don’t lie, his supervisor used to say. But James had learned something else during his seven years with the Census Bureau. Numbers don’t lie, but they can hide the truth in plain sight.

The property records showed 89 enslaved persons on the Magnolia Springs estate in Montgomery County, Alabama. The birth registry over the past 4 years showed 23 new births. The death record showed only four deaths. That meant the enslaved population should have increased by 19 persons. Yet the current count remained at 89, not 90, not 88 adjusting for sales or transfers. Exactly 89.

When James had asked the plantation’s administrator, a thin man named Virgil Krenshaw, about this discrepancy, Krenshaw had smiled, a tight, controlled expression that never reached his eyes, and said the county clerk’s office must have made recording errors. These things happened.

Paperwork was complicated, but James Hartley had checked the county records. Every birth was documented. Every infant’s name was written in careful script. And yet 19 children had vanished from the ledgers without a single transfer of sale without a single death certificate, without leaving any trace at all. The last note in his field journal, written in his own hand 3 days prior, contained just four words that now seemed to pulse on the page.

Something is very wrong. Magnolia Springs stretched across 800 acres along the Alabama River’s bend. Unlike neighboring plantations known for work songs drifting across cotton fields or Sunday gatherings where preachers brought news from other counties, Magnolia Springs existed in persistent unnatural quiet.

Travelers on the river road rarely stopped there. Those who did commented on the silence. No children’s voices, no singing, just the rhythmic sound of cotton sacks being dragged and the occasional sharp whistle that signaled shift changes. The property had belonged to the Hensley family for two generations.

Colonel Marcus Hensley, who’d inherited it from his father in 1851, ran it with military precision. He’d served in the Mexican War and brought that discipline home. Every aspect of Magnolia Springs operated on schedule, on quotota, on absolute control. But in July 1855, Colonel Hensley suffered a stroke that left him bedridden.

His wife, Margaret, had died 3 years earlier from yellow fever. Their only son, Thomas, was studying law in Boston and showed no interest in plantation management. The property fell into the hands of Virgil Krenshaw, who’d been the plantation’s bookkeeper for 8 years. Krenshaw was an unusual choice. He had no family wealth, no military background, no experience managing field operations, but he had something that made him invaluable.

He understood numbers. More importantly, he understood how numbers could be arranged to tell whatever story the viewer wanted to hear. Under Cshaw’s management, Magnolia Springs became the most profitable plantation in Montgomery County. Cotton yields increased by 30% in the first year alone. Neighboring planters asked Crenaw his secret.

He’d smile that same tight smile and say he simply optimized efficiency. What he didn’t mention were the new rules implemented within the first month of his control. Rule number one, no enslaved person could leave their assigned cabin after sundown. Rule number two, certain cabins, specifically those in the southern quarter, were strictly off limits to everyone except designated individuals.

Rule number three, questions about cabin assignments or population counts would result in immediate punishment. The overseer at the time, a man named Dutch Reynolds, had objected to rule number three. He’d worked at Magnolia Springs for 12 years and knew every person on the property by name.

The restrictions made no sense to him. Dutch Reynolds disappeared in August 1855. The official record stated he’d taken a position at a plantation in Mississippi. His wife and children, however, remained in their small house at the edge of Magnolia Springs. When asked about her husband’s sudden departure, Mrs. Reynolds would only say that Virgil Krenshaw had explained everything to her and she had no further comment.

The new overseer, Silas Beck, asked no questions at all. James Hartley returned to Magnolia Springs on a Tuesday morning in late March 1859. He’d filed his initial report, but couldn’t shake the numerical impossibility. 19 children couldn’t simply vanish without documentation. His supervisor had dismissed his concerns.

Clerical errors happened, especially in ruralcounties where recordkeeping was less rigorous. But James knew the difference between sloppy bookkeeping and deliberate concealment. This time he brought different documents, the county birth registry, the plantation’s quarterly reports to the state agriculture board, and most crucially, the water allocation records.

Every plantation was required to report water usage for crop irrigation. But the reports also inadvertently revealed something else. Residential consumption rates. Magnolia Springs water usage had increased by 34% over 4 years despite the enslaved population remaining static at 89 persons and the acreage under cultivation actually decreasing slightly.

Someone was using significantly more water. The question was who? Virgil Krenshaw met James at the main house. That familiar tight smile already in place. Mr. Hartley. I wasn’t expecting you. Routine followup, James said, keeping his tone light. Just need to verify a few residential details. Won’t take long. Krenshaw’s smile didn’t waver, but something shifted behind his eyes. Of course.

What do you need? I’d like to walk the residential quarters, count cabins, verify occupancy. Standard procedure. The silence that followed lasted perhaps three seconds, but James felt each one. The fields are quite active today, Krenshaw finally said. It might disrupt. I won’t need to speak with anyone. James interrupted smoothly.

Just a visual count. I’ve done hundreds. Very quick. Crenaw studied him, then nodded. Silus will accompany you. For your safety, of course. Some areas of the property can be hazardous. Silus Beck led James through the northern residential quarter first. These cabins housed the field workers, 18 structures, four to six persons each, exactly matching the records, everything accounted for, everything visible.

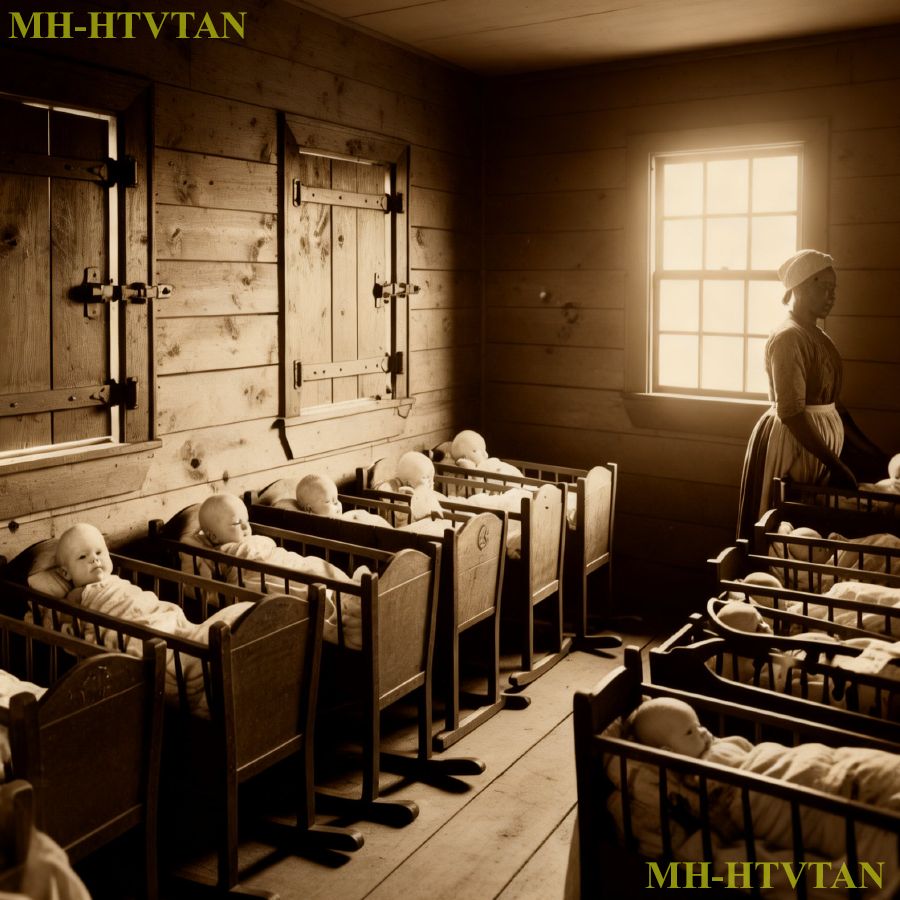

And the southern quarter? James asked. Silas’s jaw tightened almost imperceptibly. This way, the southern quarter was positioned behind a dense growth of magnolia trees that formed a natural screen. 12 cabins, smaller than those in the northern section, arranged in two precise rows. But something was immediately wrong. The windows, they were shuttered from the outside.

Heavy wooden shutters with metal latches. James had never seen residential quarters with external locks. Why are the shutters secured from outside? He asked. Security measure, Silus said quickly. Mr. Krenshaw implemented it after some property theft last year. James wrote this down, noting that locking people inside their own cabins seemed an extraordinary response to theft.

He approached the nearest cabin and peered through a gap in the shutter. The interior was dimmed, but he could make out multiple cradles. Not beds. Cradles, at least six of them in the small space. What’s the purpose of this cabin? James asked carefully. Nursery, Silus said. For the worker’s children. Seems like quite a few infants for a population of 89.

Silas said nothing. James moved to the next cabin. More cradles. Then the next also cradles. Four cabins all functioning as nurseries, all with shuttered windows that could only be opened from outside. I’ll need to see inside, James said. The children are sleeping. Mr. Krenshaw asks that we not. I’ll need to see inside.

James repeated, no longer keeping his tone light. Silas looked toward the main house, clearly calculating. Finally, he produced a key ring and unlocked the shutter on the third cabin. He pushed the window open. The smell hit James first. Milk, soiled cloth, and something medicinal.

His eyes adjusted to the dim interior. Six cradles lined the walls. Four were occupied, and every infant he could see had pale skin and light colored hair. James felt his mouth go dry. He moved to the next cabin window. Silas unlocked it without being asked this time. Resignations settling over his features. More pale-kinned babies. Seven in this cabin.

The third nursery cabin held five more. The fourth held eight. 24 white infants, all under the age of three by his estimate. all housed in locked cabins in the enslaved quarters of a plantation where no white children were listed in any official record. “Mr. Beck,” James said slowly, “I’m going to need to speak with Mr. Krenshaw immediately, and I’m going to need to see every record related to these children, every single document.

” Silus’s voice came out barely above a whisper. “You should leave, Mr. Hartley. File whatever report you need to file, but you should leave this property right now. Is that a threat? No, sir, Silas said. And for the first time, James heard something in his voice that chilled him more than anger or hostility could have. It was fear.

That’s advice from someone who wants to sleep at night. James didn’t leave. Instead, he walked directly to the main house and informed Virgil Krenshaw that he was invoking federal census authority to examine all residential records effective immediately. Krenshaw could cooperate or James would return with a federal marshall. Krenshaw’s smilefinally disappeared.

For a long moment, he simply looked at James with an expression that was difficult to read. Calculation mixed with something almost like resignation. Very well, he said quietly. The records are kept in the west office. The room Krenshaw led him to was surprisingly small, just off the main plantation office, but it was meticulously organized.

Leatherbound ledgers lined shelves labeled by year and category. Everything filed, everything indexed. Crenaw pulled down three volumes and placed them on the desk. These contain what you’re looking for. James opened the first volume. It was titled simply special residential accounts 18551 1859. The entries were coded, but James had seen enough plantation records to recognize the basic structure.

Each page detailed a transaction, a date, an origin point, a delivery notation, and a placement record. But the language was unusual. Instead of purchased or transferred, the entries used the word received. Instead of names, there were only numbers. Infant number one, infant number two, continuing sequentially. “What is this?” James asked, though something in his chest already knew.

Prrenchaw sat down across from him. When he spoke, his voice carried no emotion whatsoever. “You seem like an educated man, Mr. Hartley. So, let me ask you a question. What happens to children born to women who cannot keep them? Women who are unmarried or whose circumstances make motherhood problematic. James felt ice spreading through his veins, foundling homes, charitable institutions.

In cities, yes, but what about women in small towns, rural areas, women whose families would be ruined by scandal? Crenshaw tapped the ledger. The institutions in Mobile and Montgomery are always full. They turn away dozens every month. Those women still have babies. Those babies still need to go somewhere.

You’re telling me these are orphans, Krenshaw said. Foundlings, children who would otherwise be left on church steps or worse. We provide a service. The mothers receive discretion. The infants receive care. The plantation receives compensation for that care. Everyone benefits. James’s mind reeled. Compensation from whom? Crenshaw pulled down another ledger, this one labeled external accounts.

He opened it to show columns of payments, each linked to a numbered infant. The payment sources were coded as well, but James could see they came from various towns across Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. The families pay? James asked. Not the families directly. That would create records. We use intermediaries, lawyers mostly, sometimes doctors who attended the births.

They handle the financial arrangements. The mother never has direct contact with us. As far as she knows, her child went to a foundling home in another state. But instead, they’re here in slave cabins, locked in. We call them nurseries, Krenshaw corrected. The children are cared for by wet nurses, fed, kept clean, and healthy.

It’s far better than what most orphanages provide, I assure you. James forced himself to stay calm, to keep asking questions. For how long? What happens when they’re older? Crenaw’s expression didn’t change. That depends on what? On the arrangements made. Some families want the children to disappear permanently. Those remain here and eventually transition to field work around age 5 or six. Others, he paused.

Others want the option of reclaiming the child later once circumstances change. A hasty marriage made legitimate, for example, or a family death that provides inheritance rights. Those children are maintained separately and can be retrieved upon payment of outstanding care fees. The full horror of it crystallized in James’s mind.

This wasn’t just hiding illegitimate children. This was a systematic operation that trafficked infants, holding them as leverage, as property, as commodities. And the true genius of it, the thing that made James’ stomach turn, was how perfectly it exploited the existing plantation structure. White children held in slave quarters wouldn’t appear in white household records.

They were invisible, hidden in plain sight within a system already designed to dehumanize and conceal. How many James asked quietly. Total? How many children have passed through here? Krenshaw considered the question, then pulled down another ledger. Since we began operations in July 1855, 127 infants received.

Of those, 24 currently in residence, 31 retrieved by families, 68 transitioned to permanent placement. Permanent placement, James repeated. You mean enslaved? I mean provided with housing, food and purpose within the plantation economy. Krenshaw said many of those children would have died on the streets or in overcrowded institutions.

Here they live as slaves, white children enslaved. Children with no legal existence, Krenshaw corrected. No birth records linking them to legitimate families. No proof of free birth. In the eyes of the law, Mr. partly. These children don’t exist aswhite or colored. They simply exist, and we’ve given them a place to do so. James’ hands were shaking as he copied entries from the ledger.

He needed evidence, documentation that could be presented to authorities. But even as he wrote, a larger question haunted him. Who else knew about this? An operation this sophisticated, running for four years, involving multiple states, it couldn’t be Crenshaw alone. There had to be a network, doctors delivering the babies and arranging the transfers, lawyers handling payments, county clerks who conveniently overlooked certain registry gaps.

Perhaps even judges ensuring that questions were never asked. “I want to speak with the women caring for these children,” James said. Crenaw’s expression hardened. That’s not necessary for census purposes. I’m making it necessary. They stared at each other. Finally, Crenshaw stood. Cabin 7. But I’ll be present during the conversation.

The woman in cabin 7 was named Ruth. She appeared to be in her mid30s with careful eyes that assessed James the moment he entered. Four cradles occupied the cabin, three with sleeping infants, one empty. Ruth, Krenshaw said, his voice carrying a warning. This is Mr. Hartley from the Census Bureau. Answer his questions honestly.

Ruth’s gaze flickered between them. Yes, sir. James tried to make his voice gentle. How long have you been caring for these children? 3 years, sir, since Mr. Krenshaw set up the nurseries. And where did these babies come from? They brought to me, sir, I don’t ask questions about where, who brings them. Different people. Sometimes Dr. Whitfield from Montgomery.

Sometimes men I don’t know. They arrive at night mostly. James noted the name Dr. Whitfield. He continued, “And you feed them? Care for them?” “Yes, sir. I nursed my own baby when this started, so I had milk. Now I care for them on bottles. Goat milk mostly. Mr. Krenshaw provides what they need. What happens when they get older? When they’re no longer infants?” Ruth’s eyes lowered.

The silence stretched. “Ruth,” Krenshaw said softly. And there was something in that tone that made James’ skin crawl. “Not anger, but a reminder of some shared understanding. Some get taken back,” Ruth said quietly. “Families come for them. I clean them up, dress them nice, and they leave, and the others,” her voice dropped to barely a whisper.

They move to different cabins, learn to work, become part of the property. James felt bile rise in his throat. These are white children. How can you? He stopped himself, realizing the cruelty of the question. Ruth wasn’t the architect of this system. She was trapped in it, forced to participate or face consequences he could only imagine.

Instead, he asked, “Have any of the children ever been reclaimed?” Ruth nodded. Last month, a baby girl maybe 18 months old. A lady came for her, wore a veil so I couldn’t see her face. She cried when she held the baby, said her husband had finally died, and she could acknowledge her daughter now. Did you get her name? No, sir. Mr.

Krenshaw handled that in the main house. James turned to Krenshaw. I’ll need those retrieval records. Those are private financial arrangements, confidential. This is a federal census investigation. Nothing is confidential. For the first time, Krenshaw’s composure cracked slightly. You don’t understand what you’re interfering with, Mr. Hartley.

This isn’t some backwood scheme, the people involved. You cannot possibly comprehend the reach of this network. Then help me comprehend. Give me the names. Krenshaw stared at him for a long moment. Then, unexpectedly, he laughed. A short bitter sound. You want names? Fine.

I’ll give you names, but first let me show you something. Back in the records room, Krenshaw pulled down a locked box from the top shelf. He opened it with a key he wore on a chain around his neck. Inside were letters, dozens of them bundled with ribbon by year. Correspondence, Crenshaw said, spreading several across the desk. Read them. James picked up the first letter.

It was dated September 1856. written on expensive stationery with an embossed header from a law firm in Atlanta. The language was formal, discussing placement arrangements for client matter number 47 and confirming discretionary fund transfer of $800 for ongoing residential care. The next letter came from an address in Savannah written in elegant feminine script.

It begged for updates on the child I entrusted to your care in April and included a money order for $200 with a plea that every comfort be provided. James read letter after letter. Some were clinical and business-like. Others were heart-wrenching mothers desperate for news promising any amount of money to ensure their children were healthy and safe.

Several referenced future retrieval once circumstances permitted. One letter dated January 1858 was different. It came from a law office in Montgomery, only 20 mi away. The language was threatening. It stated that the child designated as infant the 89must be returned immediately and warned that failure to comply will result in legal action that will expose this entire enterprise.

There was a response letter clipped to it written in Cshaw’s precise handwriting. It was brief. Infant D89 deceased due to fever. December 1857. Death unregistered as per original arrangement. No refund issued. Further contact will result in disclosure of client identity to relevant parties. James looked up. You threatened to expose them.

I provided facts. Krenshaw said the arrangement was confidential on both sides. They wanted discretion. So did we. Mutual assured silence is the foundation of this entire system. This letter says the child died. Did infant number 89 actually die? Crenshaw smile returned. According to our records, yes. But in reality, in reality, Mr.

Hartley, these children have no legal existence. If we say a child died, they died. If we say they never existed, they never existed. The beauty of this arrangement is that no one can prove otherwise. The mothers have no rights. They’ve already abandoned legal claim by hiding the birth. The children have no documentation. They’re ghosts.

James felt cold spreading through his chest. How many of the recorded deaths are real? Some, Crenaw said simply, “Infants are fragile. Disease happens. But yes, some of the death records are administrative fictions. Useful when a family becomes problematic or when payment stops or when a child is more valuable remaining invisible.

What happens to those children? The ones declared dead but still alive. Crenaw closed the ledger. They transition to fieldwork earlier by age four. Usually assigned new names, integrated into the general population. Within a few years, no one remembers they weren’t always here. They’re just part of the property count.

James had to grip the desk to steady himself. The full scope was becoming clear. This wasn’t just hiding illegitimate children. This was a machine that could make inconvenient children vanish either temporarily or permanently while extracting ongoing payment from desperate families. And any child whose family stopped paying or became troublesome could be effectively erased from existence by simply declaring them dead and transitioning them into enslavement.

Who else knows? James asked about all of this? Crenshaw walked to the window looking out over the plantation. The network includes three similar operations, one in Mississippi, one in Georgia, one in South Carolina. coordinated by certain gentlemen who saw an opportunity in the intersection of social scandal and existing agricultural infrastructure.

The operations generate approximately $40,000 annually across all sites. That money is distributed among various stakeholders. Stakeholders, James said, you mean accompllices? I mean individuals who ensure the system functions smoothly, doctors who identify suitable candidates, lawyers who arrange transfers and payments, county clerks who manage birth registry discretion, state officials who overlook plantation reporting irregularities, even certain federal employees who might be inclined to question census discrepancies.

The implication hung in the air. You’re trying to bribe me. I’m offering you perspective. Your annual salary is what? $600. We could provide you with 10 times that. For doing nothing except filing a census report that shows everything in order. No discrepancies, no irregularities, just numbers that add up correctly.

James stood, gathering his copied documents. I’m filing a report with the federal marshall’s office. This operation ends. Crenshaw didn’t move from the window. Before you do that, let me ask you something. What do you think happens to those 24 infants if this operation is exposed? Their births are unregistered. Their mothers are anonymous. Legally, they don’t exist.

So, when you shut this down, where do they go? James stopped at the door. There’s no legal mechanism to return them to families who officially never had them. Krenshaw continued, “No orphanage will take children with no birth records. The state has no category for them. So, I’ll tell you exactly what happens.

They become wards of the county. And in Alabama in 1859, Mr. Hartley, white children with no legal existence become, well, they become whatever someone with the right paperwork says they are. The system you’re trying to dismantle is the only thing protecting those children from complete legal oblivion. James felt the terrible weight of the dilemma. Crenaw was right.

Exposing this would save future children from being funneled into this network, but the children already here would fall into a legal void that might be even worse. “There has to be a way,” James said. “There isn’t,” Krenshaw replied. “Not in the current legal framework. So, you have a choice, Mr. Hartley. Shut this down and condemn 24 children to legal non-existence or accept that in an imperfect world, imperfect solutions sometimes serve the greater good. Jamesleft without answering.

James spent the next two weeks investigating from Montgomery. He filed no official report, but he followed every threat he could find without revealing his purpose. Dr. Whitfield, the physician Ruth had mentioned, maintained a respectable practice in Montgomery’s wealthiest district. His patient list included senators wives, judges daughters, prominent merchants families.

James couldn’t approach him directly without tipping off the network. Instead, James focused on the records. He cross referenced birth registries with death records, looking for patterns. What he found was subtle but telling. Certain families showed no births during years when neighbors reported seeing the woman in late pregnancy.

Medical consultations filed, but no corresponding birth entry. Women who traveled for extended rest in the months before a child’s expected arrival. He found 17 such cases in Montgomery County alone over the past 4 years. 17 families where circumstantial evidence suggested a birth that was never officially recorded.

He also found something else. Judicial review records. Three cases where plantation population counts had been questioned by tax assessors, noting discrepancies similar to what James had observed. All three investigations had been closed with brief notations. Clerical error resolved or recount confirmed accuracy. Two of those closing signatures came from the same county judge, Judge Harrison Caldwell.

James requested a meeting with Judge Caldwell under the pretense of census methodology consultation. The judge was a distinguished man in his 60s with silver hair and the careful diction of someone educated at prestigious institutions. Mister Hartley. The judge greeted him warmly. I understand you have questions about population verification procedures.

James laid out his concerns in abstract terms, talking about theoretical discrepancies, asking about legal frameworks for resolving census irregularities. The judge listened patiently, offering procedural advice that was technically correct but utterly useless for James’s actual situation. Finally, James took a calculated risk.

Judge Caldwell, if someone discovered children being held illegally on a plantation, what would be the proper legal recourse? The judge’s expression didn’t change, but something shifted in his posture. That’s an interesting hypothetical. What sort of children? Theoretically, white children with no recorded births. I see. The judge stood and walked to his bookshelf, pulling down a volume of Alabama state law.

He flipped to a section and showed it to James. Under current statutes, a child’s legal status is determined by maternal status at birth. If the birth occurred in a legitimate marriage, the child is legitimate. If not, the child has no automatic legal rights. Establishing such rights requires a complex legal process involving testimony, documentation, and court proceedings.

But if the birth was never recorded, then legally the birth never occurred. The child exists in a state of legal quantum, neither fully recognized as a person with rights nor proven to not exist. It’s a gap in our legal framework, I’ll admit. One that occasionally creates complications. James understood.

The judge was telling him that even if he exposed the operation, the law itself provided no clear remedy. These children had been engineered to exist in a legal blind spot. What would you do, Judge Caldwell, if you discovered such a situation? The judge closed the book carefully. I would consider the consequences of any action. Sometimes, Mr.

Hartley, the law is an imperfect instrument for achieving justice. Sometimes the choice is between a hidden wrong that provides some stability versus an exposed wrong that creates chaos no one is prepared to manage. As James left the courthouse, he realized with sinking certainty that Judge Caldwell was part of the network. Not an active participant perhaps, but certainly aware and willing to ensure legal roadblocks remained in place.

James’ breakthrough came from an unexpected source. A young lawyer named David Foster contacted him, requesting a private meeting at a tavern outside Montgomery. Foster looked exhausted when they met. dark circles under his eyes, suggesting many sleepless nights. He ordered whiskey and drank half of it before speaking.

“I heard you visited Judge Caldwell asking about plantation irregularities,” Foster said quietly. “I need you to understand something. I was part of this. I facilitated four placements at Magnolia Springs. I thought I told myself it was helping desperate women, giving babies a chance they wouldn’t have otherwise. What changed? James asked. I made a mistake.

I kept correspondence. Earlier this year, one of my clients, a young woman whose family would have disowned her, she became pregnant by a man who refused to marry her. I arranged for her child to be placed at Magnolia Springs through the usual channels. But afterward, shehad a breakdown. Attempted to harm herself, kept crying about wanting her baby back.

Foster pulled a letter from his jacket and slid it across the table. I contacted Crenaw 6 weeks ago arranging retrieval offering to pay double the accumulated fees. This was his response. James read the letter. It was brief and devastating. Infant number young 124 male deceased March 3rd, 1859. Respiratory fever. No retrieval possible. Outstanding fees still owed.

The child died? James asked. That’s what I thought initially. I informed the mother. She’s been inconsolable. But then 3 days ago, I was in Selma on other business. I saw a woman with a child, a boy maybe 6 months old, same age, infant number 124 would be. The woman was purchasing supplies and when she paid, I saw her name on the account receipt. Mrs.

Adelaide Brennan, Asheford Plantation, Willox County. And Mrs. Adelaide Brennan died in 1857. Kalera outbreak. That’s public record. So who was this woman using her name? And why did that child have a distinctive birthmark on his left hand? The same birthark my client mentioned her baby having. James felt his pulse quicken.

You think the child was declared dead but actually transferred to another plantation? I think Krenshaw has multiple revenue streams. families pay for care, but he also sells the children to other plantations once they’re weaned, claims they’re dead, pockets the ongoing care payments for a few more months to avoid suspicion, and generates additional income from the sale.

The families never know because they have no way to verify. They can’t publicly search for children they’re not supposed to have. Do you have proof? Only circumstantial observation. But if you investigate Ashford Plantation in Wilcox County, I suspect you’ll find similar nursery operations. And if you check property transfer records between plantations in this region, you might find unusual patterns of asset movements that don’t correspond to adult enslaved persons. Foster finished his whiskey.

I can’t testify to any of this. If my involvement is exposed, I’ll be disbarred and possibly criminally charged. But I can’t sleep anymore, Mr. Hartley. I keep seeing that woman’s face when I told her baby died. I need you to know the truth, even if I can’t help reveal it publicly. Following Fosters’s lead, James began mapping the network.

He requested census and property records from surrounding counties, looking for patterns. What he discovered was staggering in its scope. Ashford Plantation in Wilcox County showed the same statistical impossibility. births recorded but population remaining static. So did Riverside Estate in Georgia and Crescent Hill in Mississippi.

All four properties were owned by different families but shared two common elements. Each had undergone management changes around 1854 1855 and each showed the same pattern of water usage increase without corresponding population growth. James created a timeline. The operation appeared to have started in Mississippi in late 1854.

Georgia came online in early 1855. Alabama’s Magnolia Springs began in July 1855. South Carolina’s operation started in spring 1856. All within an 18-month period. The coordination required for this expansion suggested serious capital investment and highlevel planning. This wasn’t opportunistic. It was strategic. James also found the money trail buried in county tax records.

All four plantations paid quarterly consultation fees to a firm called Southern Agricultural Advisers based in New Orleans. The firm existed on paper but had no physical office. Its registration documents listed three founding partners. Virgil Krenshaw, a Mississippi plantation manager named Robert Styles, and a New Orleans attorney named Charles Meredith.

Charles Meredith was the Keystone. His law practice specialized in estate planning and discreet family matters. He had connections throughout the South’s upper class, and according to city records, he owned a significant share in a medical clinic in New Orleans that advertised confidential services for delicate family situations.

The entire network clicked into focus. Meredith’s clinic identified pregnant women in crisis. His legal practice arranged the placements and payments. The four plantations provided physical locations that were geographically distributed to reduce suspicion. Local doctors and lawyers in various towns served as contact points and a carefully selected network of officials, clerks, judges, tax assessors ensured that inconvenient questions were never pursued.

It was brilliant. It was monstrous. And James had no clear way to dismantle it without harming the very children he was trying to protect. James sat in his boarding house room, surrounded by documents and notes, trying to find an answer that didn’t exist. If he filed an official report exposing the network, it would trigger investigations.

Arrests would be made, the plantations would be raided, and 24 white infants atMagnolia Springs, plus however many at the other three locations, would become legal non- entities that no institution was equipped to handle. In 1859 Alabama, there was no social services system, no child protective framework.

Those children would likely end up exactly where Krenshaw had threatened. Declared as enslaved property through fraudulent documentation because that was the only existing legal category that could absorb them. If he did nothing, the network would continue. More desperate women would be exploited. More children would be funneled into this system, some eventually enslaved, some held as leverage, all existing in a legal shadow.

And if he tried to expose only part of the network, perhaps targeting the retrieval fraud without dismantling the entire operation, he’d simply force the system to evolve to cover its tracks more carefully. There was a knock at his door. When James opened it, he found a well-dressed man he’d never seen before. Mr. Hartley, the man said.

My name is Charles Meredith. I believe we should talk. Meredith sat in James’s single chair with the comfortable authority of someone accustomed to controlling conversations. He declined the offered whiskey and went straight to his purpose. Mr. Krenshaw informed me of your investigation. I’ve reviewed your background.

Yale education family in Connecticut posting to Alabama Census Bureau. You’re qualified for much better positions. Why are you still counting plantation populations in rural counties? I do my job, James said carefully. Admirably, which is why I’m here. The network you’ve uncovered serves an important function. Whether you recognize it or not, every year, hundreds of women in the South face impossible situations.

Our society offers them no options except shame and ruin. We provide a third option. Is it perfect? No. But it’s better than the alternatives. You’re selling children. We’re providing care for children who would otherwise be abandoned to die. And yes, we charge fees because maintaining these nurseries, employing wet nurses, ensuring medical care all requires resources.

The fees ensure sustainability. And the children who are declared dead but sold instead. Meredith’s expression didn’t change. Unfortunate, but necessary adjustments. Some families become liabilities. Some children are more valuable as permanent placements. The system requires flexibility. That’s not flexibility.

That’s fraud and enslavement. In the eyes of the law, you cannot enslave someone who legally doesn’t exist. Meredith countered. These children have no birth records, no family claims, no legal personhood. We’ve given them existence within the only framework available. Is it ideal? No. Is it survival? Yes. James shook his head. I’m filing my report.

And condemning those 24 children at Magnolia Springs to what exactly? You’ve seen the legal reality. There’s no mechanism to help them. Your report will simply force them further into the shadows. Whereas, if you accept our offer, $5,000 annually, Mr. partly for doing nothing except filing accurate but unremarkable census reports.

Those children remain fed and cared for. Future placements continue to save desperate women, and you gain the financial freedom to eventually pursue the better positions you’re qualified for. Blood money, reality money. The world is imperfect, Mr. Hartley. We didn’t create these social conditions. We’re simply managing the consequences as humanely as possible within existing constraints.

Meredith stood to leave. At the door, he paused. You have until Friday to decide. File your report and face the consequences. Legal chaos, personal danger, and the knowledge that you’ve helped no one. Or accept that some problems have no perfect solutions, only managed imperfections. I’ll await your decision. James didn’t sleep.

He sat at his desk reviewing documents until his eyes burned, searching for some legal pathway he’d missed. At midnight, there was another knock. This time, when he opened the door, Ruth from cabin 7 stood in the hallway. “She was alone, breathing hard like she’d been running. “I shouldn’t be here,” she whispered urgently.

“If they know I left, come in,” James said, pulling her inside. “What happened?” Ruth’s words tumbled out. You asked what happens to the children. I didn’t tell you everything. Couldn’t. Not with Mister Krenshaw there. But you need to know. She explained that the nursery cabins James had seen held only the infants still being maintained for potential family retrieval.

The ones whose families were still paying. But there were other children. ones who’d been declared dead to their families but were actually alive transitioned into the general enslaved population. “How many?” James asked. “I’ve counted at least 32 over 4 years. They stop being in the nursery cabins.

They get moved to the far cabins near the processing barns, given different names. The younger ones forget they were ever anything else. But some of the olderones, the four and 5year-olds, they remember fragments. They’ll say things about having a different name before, about rooms with locked shutters. Where are they now? Scattered across the plantation mixed in.

Some field work, some domestic work in the main house. There’s a boy in the stables, maybe 6 years old, light hair, light eyes. He serves meals sometimes. I heard Mr. Krenshaw call him proof of concept. James felt sick. Proof of what concept? That it works? that you can hide white children in the enslaved quarters and no one notices, no one questions.

After a few years, they’re just part of the property, and if they’re part of the property, they can be sold.” James finished quietly. Ruth nodded. 3 months ago, a man came from Louisiana. He and Mr. Krenshaw walked the quarters. The man was looking at specific children, all under age seven, all light-skinned. He purchased four of them.

I saw the bill of sale. It listed them the same as any other property transaction. Do you know the buyer’s name? William Porter, Claybornne Parish, Louisiana. The bill of sale is in the records room filed under Agricultural Asset Transfers Q41 1858. James wrote this down with shaking hands. Why are you telling me this? You’re risking everything.

Ruth’s eyes glistened. Because I have a daughter. She’s 12 now, works in the laundry house, and every day I look at these white babies and think about how their mothers gave them up to save them from shame. But all they did was trade one kind of suffering for another. Those mothers think their children are safe, being cared for, maybe even happy.

They don’t know the truth. And I keep thinking, someone should know the truth. Even if nothing changes, someone should know. On Thursday morning, James made his decision. He took his documented evidence to Federal Marshal William Cross in Montgomery. Cross had a reputation for integrity, a rare quality in Alabama’s political landscape.

James laid out everything. the nursery cabins, the locked shutters, the 24 visible infants, the estimated 32 children transitioned into enslavement, the payment network, the four coordinated plantations, the complicit officials. Cross listened in silence, his expression growing darker as the testimony continued.

When James finished, Cross asked only one question. Can you prove the children’s original identities? connect even one child to a specific family of origin. No, James admitted the whole system is designed to eliminate that proof. Anonymous placements, coded records, no direct family contact. Cross leaned back. Then we have a problem.

Without proving free birth, we cannot legally remove them from plantation property. The plantation owner can simply claim they were born to enslaved mothers on the property. And if we cannot prove otherwise, there has to be something, James said desperately. Cross thought for a long moment. There might be one approach.

If we can prove fraud in the financial transactions, specifically that families were charged for care that wasn’t provided or that children were declared dead when they weren’t, we can build a case for criminal fraud. That gives us legal grounds to raid the plantation and seize all records. Once we have documentation of the original placements, we might be able to reconstruct identities. Might.

It’s the best option available. But James, you need to understand what you’re triggering. If this network involves the people you think it does, prominent families, judges, wealthy lawyers, there will be significant pressure to bury this. And people who threaten powerful interests sometimes face unfortunate accidents.

I understand. I hope you do, Cross said grimly. Because once I file this with the federal prosecutor, there’s no taking it back. The federal raid on Magnolia Springs occurred at dawn on April 12th, 1859. Eight marshalss, including Cross himself, arrived with a warrant authorizing seizure of all financial and residential records related to suspected interstate fraud and conspiracy.

Virgil Krenshaw didn’t resist. He simply stood on the main house porch, watching as marshals carried out boxes of ledgers while others documented the nursery cabins and photographed the locked shutters. James was there, though not in an official capacity. He watched as they brought out the 24 infants, each wrapped in blankets, crying from the sudden disruption.

Ruth and three other women accompanied the children, trying to keep them calm. “Where are you taking them?” Ruth asked one marshall. The marshall looked uncomfortable. “County facility temporarily until we sort out the legal status.” “The county has no children’s facility,” James said quietly. The marshall’s expression confirmed what James already knew.

They were taking the children to the county poor house, a grim facility designed for destitute adults, not infants. But at least they’d been removed from the plantation. That was something. The real discovery came when marshals searched the far cabins Ruthhad mentioned. They found 18 children between ages 3 and seven working in various capacities around the plantation.

All had light skin and features that stood out among the primarily dark-skinned enslaved population. When questioned, most couldn’t clearly articulate their origins. The younger ones believed they’d always been at Magnolia Springs, but a few of the older children remembered fragments being in a different place before, having a different name, women’s voices crying.

One girl about 6 years old told a marshall she remembered being called Anna before, but now everyone called her Lucy. She remembered a room with a window she couldn’t reach and a woman who sang to her in a language she didn’t understand anymore. When asked if she remembered anything else, she said only. The lady said she’d come back, but she never did.

Federal prosecutors filed charges against Virgil Krenshaw, Charles Meredith, Dr. for Whitfield and 17 other individuals, including two county clerks and one state administrative official. The charges included fraud, conspiracy, falsification of public records, and child trafficking. The trial was scheduled for September 1859 in federal court. It never happened.

In July, a Mississippi congressman invoked procedural challenges, arguing that federal jurisdiction didn’t apply to internal state matters involving property and residency. Alabama’s attorney general filed a supporting brief. By August, the case was embroiled in jurisdictional disputes that would take months to resolve.

Meanwhile, key evidence began disappearing. Ledges that had been seized went missing from the federal evidence room. Two of the lawyers who’d been prepared to testify as witnesses suddenly recanted their statements, claiming they’d been mistaken or coerced. Doctor Whitfield produced documentation showing he’d been treating patients in Mobile during every date James had placed him at Magnolia Springs.

Documentation that was clearly fabricated, but impossible to disprove without extensive investigation. Most devastatingly, six of the 18 children removed from Magnolia Springs disappeared from the county poor house within 3 weeks. The facility administrator claimed they’d been claimed by relatives, but could produce no documentation of who these relatives were or where the children had been taken.

James understood what was happening. The network was protecting itself, using wealth and influence to dismantle the case from within. Federal Marshall Cross fought hard, but by October, the prosecutor’s office announced they were dropping the charges due to insufficient evidence and procedural complications. Virgil Krenshaw walked free.

So did Charles Meredith. So did everyone except one county clerk who lacked the connections to protect himself and was convicted of falsifying records. Sentenced to 2 years serving only 8 months. The 24 infants who’d been in the nursery cabins were eventually distributed among three church-run institutions in different states.

Whether their families ever learned they were alive, James never discovered. The 12 children who remained from the group of 18 were processed through a newly created state guardianship system that essentially indentured them to various families as domestic workers until age 18. and the operation itself. Publicly it ended.

Magnolia Springs was sold to new owners who had no connection to the previous management. The other three plantations similarly changed hands. But James noticed something in the records from late 1859 and early 1860. Two new plantations in Arkansas and one in Tennessee began showing the same statistical patterns. Increased water usage.

static populations despite recorded births, management by recently appointed administrators who had no prior plantation experience. The network hadn’t ended. It had simply migrated. In November 1859, James received a letter at his boarding house. No return address. Inside was a single sheet of paper with a brief message.

You asked if the children could be saved. The answer was no. They could only be redistributed. The system is larger than any one plantation, larger than any individual, larger than your investigation. It exists because society creates a need for it. Until that changes, operations like Magnolia Springs will continue in different forms under different names.

You did what you believed was right. I respect that. But you should know that the 18 children removed from Magnolia Springs are being monitored. Should any of them upon reaching adulthood attempt to speak publicly about their experiences or origins, arrangements have been made to ensure their credibility is destroyed. Financial incentives for silence have been offered to the institutions housing them.

This is not a threat to you personally. Your investigation is concluded. The case is closed. Continue your census work. Make no further inquiries into this matter. That is the only way to ensure no additional complications arise. The children are assafe as they can be given the circumstances. That will have to be sufficient. The letter was unsigned.

James burned it immediately. But he kept copies of all his investigative documents hidden in a safety deposit box in Montgomery under a false name. In December 1859, James requested a transfer to the Census Bureau’s office in Philadelphia. His supervisor approved it without question. James suspected someone had encouraged his relocation, a quiet way to remove him from the region.

Before leaving Alabama, James made one final visit to Magnolia Springs. The new owner, a plantation family from Virginia, had already begun operations. The southern quarter with its nursery cabins had been converted to storage facilities. James walked past cabin 7. The shutters were gone. The door stood open.

Inside he could see barrels of seed and coils of rope. No cradles, no trace that children had ever been there. A field supervisor noticed him and called out, “Can I help you with something?” “Just passing through,” James said. “Looking for someone who used to work here.” “Woman named Ruth.” The supervisor shook his head. Don’t know that name.

The previous ownership sold off most of their workers when they left, scattered to different properties across the state. James nodded and walked back to his horse. He’d expected that the network would have ensured that anyone who knew too much was dispersed, separated, made difficult to locate. As he rode away from Magnolia Springs for the last time, James thought about the girl who remembered being called Anna before becoming Lucy, wondered if she still remembered, or if time and circumstance had erased even that fragment of her original identity. He

wondered how many children across the South existed in that same liinal space, legally non-existent, their origins erased, their futures determined by systems they couldn’t comprehend or escape. James Hartley spent 23 more years with the Census Bureau, eventually becoming a regional director in Pennsylvania.

He never returned to Alabama. He never spoke publicly about what he’d discovered at Magnolia Springs. But he kept the documents, every letter, every ledger copy, every note from his investigation. He organized them meticulously, creating a comprehensive archive of the network’s operations during that brief period when it had been partially exposed.

In 1881, James donated this archive to the Pennsylvania Historical Society under a restricted access agreement. The materials were to be sealed until 1920, 61 years after the investigation, long enough that anyone directly involved would likely be deceased. The donation receipt listed the contents simply as documents relating to census irregularities and child placement practices in Alabama 1855-1859.

James died in 1882, one year after making the donation. His obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer described him as a dedicated public servant and meticulous recordkeeper who contributed significantly to census methodology improvements. There was no mention of Magnolia Springs, no reference to the investigation that had consumed 6 months of his life and haunted his conscience for decades after.

The archive remained sealed until 1920, as James had specified. When a graduate researcher named Eleanor Shaw accessed it while studying post civil war reconstruction, she found the full documentation of the Magnolia Springs network. All the evidence James had been unable to use effectively. Eleanor’s research revealed additional details that James hadn’t known.

Records from the postwar period showed that several of the children who’d been removed from Magnolia Springs in 1859 had tried to reclaim white identity as adults. All had been unsuccessful. Without birth records proving free birth, they couldn’t establish legal white status. They existed in a legal gray area throughout their lives, facing discrimination from both white and black communities.

She also found correspondents suggesting that similar operations had continued well into the 1870s, adapting as legal frameworks changed. The network had been more resilient than anyone realized. But the most disturbing discovery was a set of estate records from 1903. When Charles Meredith, the New Orleans lawyer who’d coordinated the network, died.

His estate papers included a private ledger found in a locked desk drawer. This ledger contained the real names, birth mothers matched to infant numbers, original placement dates, retrieval arrangements, death declarations, both real and fabricated. It documented 412 children processed through the for plantation network between 1854 and 1861.

Of those, 89 were retrieved by families. 114 were recorded as deceased, though the ledger marked 67 of those deaths with a small asterisk suggesting they were administrative fictions. The remaining 200 had nine were listed as integrated assets with transfer records showing they’d been sold to various plantations across the South.

Elellanar spent 3 years trying to trace whathappened to those 209 children. She found fragments, property records showing childaged workers purchased from the four network plantations, postwar Freriedman’s Bureau documents showing individuals who couldn’t establish birth origins. a few obituaries of elderly persons who’d spent their entire lives unable to prove whether they’d been born free or enslaved, leaving them in legal limbo even after emancipation.

But complete stories, full accounts of what those children experienced, how they lived, whether they ever learned their true origins, those were lost to time. Elellanena’s research did uncover one complete account. In 1924, while interviewing elderly former enslaved persons for a historical project, she met a woman named Lucy Henderson in Selma, Alabama.

Lucy was 69 years old, living in a small house she’d purchased with savings from 40 years of domestic work. During the interview about her experiences during slavery and reconstruction, Lucy mentioned something unusual. She said she had dreams sometimes. Dreams that felt more like memories about a different time before the plantation.

I was very young, Lucy told Eleanor. Maybe four or five, but I remember a woman with soft hands who used to hold me by a window. She sang songs I didn’t understand. And she called me something else, not Lucy. It sounded like Anna, maybe or something close. Elellanena felt her heart race. She’d seen that name in James Hartley’s notes.

The six-year-old girl at Magnolia Springs who remembered being called Anna. “Do you remember anything else about that time?” Elellanar asked carefully. Lucy was quiet for a long moment. I remember the woman crying. She held me very tight and kept saying she was sorry. Then men came and took me, put me in a carriage.

It was dark inside. When we arrived somewhere, they put me in a room with other children. The windows had shutters I couldn’t open. Magnolia Springs. Lucy looked at Elellanena with sharp knowing eyes. You’ve heard about that place. Eleanor nodded slowly. I figured it out eventually.

Lucy said, “Took years, but I put the pieces together. I wasn’t born enslaved. I was put there. Someone gave me away and someone else made money from it. And when they couldn’t profit from me anymore, they just kept me. easier than explaining where I came from. Did you ever try to find out who you were? Your original family? Lucy’s laugh was bitter.

How? I had no name except what they gave me. No birth record. No proof I even existed before Magnolia Springs. After emancipation, I tried, went to courouses, asked questions. But without documentation, I was just another freed woman with a story no one could verify. White families certainly weren’t going to admit to having a missing child who ended up enslaved.

“I’m sorry,” Elellanena said, feeling the inadequacy of the words. “Don’t be sorry, be accurate.” Lucy leaned forward. Lucy leaned. “If you’re writing about this, if you’re recording what happened, you make sure people understand it wasn’t just evil individuals. It was a system. a system designed to exploit desperate women and erase inconvenient children.

And it worked because society wanted it to work because acknowledging those children’s existence would have been more uncomfortable than pretending they didn’t exist. Elellanar promised she would be accurate. She spent two more days interviewing Lucy, documenting everything she remembered about Magnolia Springs, the other children, the transition from nursery cabin to enslaved quarters, the years of living with fractured identity.

Lucy Henderson died in 1926. She had no children, no husband, no living relatives that she knew of. Her obituary in the Selma Times Journal was three sentences long and made no mention of her origin or her experiences. Elellanena Shaw’s research became her doctoral dissertation, though it was considered too controversial for publication at the time.

Her papers were eventually archived at the University of Alabama in 1958, where they remained largely unexamined until recently. Modern researchers attempting to verify the scope of the Magnolia Springs network have found it nearly impossible to determine exact numbers. Census records from the 1850s are incomplete. Plantation ledgers were often destroyed during the Civil War.

Many of the key participants left no personal papers, but by cross-referencing James Hartley’s confiscated documents, Charles Meredith’s private ledger, Elellanena Shaw’s research, and fragmentaryary records from the four plantations involved. Historians have estimated that between 400 and 500 children passed through the network during its roughly 7 years of peak operation.

Of those children, approximately 90 were retrieved by families. Approximately 180 were transitioned into permanent enslavement. Approximately 140 were recorded as deceased, though how many actually died versus being declared dead for administrative purposes remains unknown.

The remainder are unaccountedfor, their fates lost to incomplete documentation. After the civil war, some of these children would have be and emancipated along with all enslaved persons. But without birth records proving free origin, they faced unique challenges in establishing legal identity. Several appear in Freriedman’s Bureau records as individuals seeking documentation of birth status, unable to prove they’d been born free, but also unable to definitively prove they’d been born enslaved.

The legal ambiguity that had made them invisible before emancipation continued to plague them after. As for the network’s organizers, Virgil Krenshaw moved to Texas in 1860 and died there in 1873. Charles Meredith continued his legal practice in New Orleans until his death in 1903. Dr. Whitfield practiced medicine in Montgomery until 1889.

None were ever convicted of crimes related to the network. Judge Harrison Caldwell served on the bench until 1878 and was remembered in his obituary as a distinguished jurist who served Alabama with integrity for over 30 years. In 1998, a construction crew renovating the former Magnolia Springs property, which had been converted to a corporate retreat center in the 1960s, discovered something beneath the foundation of what had been cabin 12 in the southern quarter.

Buried in a shallow space were seven small wooden markers, the kind someone might carve by hand. Each bore a name and a date from the 1850s. Thomas, March, 1856. Elizabeth, November 1856. Sarah, July 1857, and four others. The names didn’t match any recorded deaths in Montgomery County records. They didn’t appear in Magnolia Springs official documentation.

They existed only on these hidden markers, buried where someone had wanted them remembered, even if they couldn’t be publicly acknowledged. Were these the children who’d actually died in the nursery cabins? Or were they markers for children who’d been declared dead but lived on somewhere under different names? The person who’d carved and buried those markers never identified themselves.

Their motivation remains unknown. The markers are now housed in the Alabama Department of Archives and History, cataloged simply as unidentified wooden markers, origin unknown, approximately 1856 1857. Among James Hartley’s papers donated with his archive to the Pennsylvania Historical Society, was one final document.

It appeared to be a letter he’d started writing multiple times, but never sent. Various drafts were crossed out, rewritten, abandoned. The final version, dated March 1860, almost exactly one year after his first visit to Magnolia Springs, read, “To whom it may concern, I discovered a system that exploited vulnerable women and erased children’s identities for profit.

I gathered evidence. I reported it to proper authorities. I did everything according to law and procedure. The system adapted. The children were not saved, only relocated. The perpetrators were not punished, only inconvenienced. And I am left with the knowledge that my investigation may have made things worse for some of those children, removing them from imperfect care and placing them in worse situations.

I do not know what the right action would have been. I only know that what I did was insufficient. If someone reads this record in the future, understand this. The horror of Magnolia Springs was not just what Crenshaw did. It was how easily the system absorbed it. How many people knew something was wrong, but did nothing.

How the law itself provided no mechanism to protect children who’d been deliberately placed outside its protection. The question is not whether such operations could happen. Clearly, they did. The question is how many others existed that no one investigated? How many children vanished into legal shadows while everyone who might have helped looked away? I have no answer to offer.

Only this documentation so that at least their existence is recorded somewhere. Even if their names are lost, even if their stories can never be fully told, this record proves they were real. They existed. They mattered. That is all I can give them now. The letter was unsigned and undated in final form, though the draft showed it had occupied James’s thoughts throughout 1860.

Whether he ever intended to send it or to whom remains unclear. When the Census Bureau’s complete archives from the 1850s were digitized in 2003, researchers discovered James Hartley’s original field notes from his Alabama assignment. Among the routine notations about cotton yields and property measurements was a handwritten addendum dated March 29th, 1859.

Magnolia Springs Plantation official population count confirmed at 89 persons. Residential facilities documented and measured. All records appear in order for census purposes. Personal notation not for official report. The numbers are correct. That is precisely what is wrong with them. Those two sentences, the official statement and the personal truth beneath it, perhaps best capture the entirety ofwhat happened at Magnolia Springs.

A system where everything appeared correct on paper, where every number balanced, where official records showed nothing a miss. And beneath that facade of order, children disappeared into shadows so deep that more than a century later, we still cannot say with certainty how many there were, who they became, or whether any of them ever learned the truth about where they came from.