Admiral Hail thought he was just kicking an intruder out of an elite military funeral. In his immaculate uniform, he looked down at the old man in the shabby suit and laughed in his face. He mocked the stranger’s appearance and even called his rusted dog tags trash, accusing him of stolen valor for the whole crowd to hear.

But the admiral made a fatal mistake. He didn’t know that the silent man he was humiliating wasn’t just some civilian. He was a black ops ghost legend known only as Payback. And when a four-star general arrived and walked right past the admiral to salute the old man, the shocking truth would leave everyone breathless.

Is this some kind of joke? Admiral Marcus Hail’s voice cut through the quiet reverence of Quantico National Cemetery like a blade through silk.

He stood with his arms crossed, his dress blues immaculate, the twin stars on his shoulders catching the late morning sun. His posture radiated authority, or at least the appearance of it, the kind of authority that came from connections and careful career management rather than earned respect.

Before him stood Frank Castaniano. At 74, his frame was lean and weathered, his shoulders slightly stooped by time, but not by spirit. He wore a simple dark suit, the fabric worn thin at the elbows, the cuffs frayed, but clean. It was the only suit he owned. He didn’t need another. His face was a road map of a life lived hard. Deep lines carved around his eyes, a scar running from his left ear to his jawline, the kind of mark that came from close quarters fighting.

His hands, calloused and spotted with age, hung relaxed at his sides. He said nothing, his pale blue eyes, clear despite his years, remained fixed on the rows of white headstones stretching across the green hills beyond the admiral. The funeral was for Major General Andrew Richards, USMC, retired. A man who’d commanded respect not through rank alone, but through the kind of leadership that made Marines willing to follow him into fire.

The gathering was small but distinguished. Colonels, a few generals, politicians with solemn faces, and family members dressed in black. The flag draped casket sat beneath a white tent, waiting for the final honors. Castellano had arrived quietly, parking his old Ford truck in the visitor lot and walking the quarter mile to the grave site. He hadn’t announced himself.

He never did. He’d simply come to pay his respects to a man who’d understood what it meant to bring your people home. no matter the cost. Admiral Hail had noticed him immediately. Not because of any uniform or insignia. Castiano wore none, but because the old man didn’t belong. At least that’s what Hail thought.

The admiral prided himself on knowing who mattered at these events. And this weathered stranger in a threadbear suit was definitely not on the guest list. “Sir, this is a private ceremony,” Hail continued, stepping closer. His voice carried that particular condescension reserved for people he considered beneath him. I’m going to need you to show me your invitation or I’m going to have to ask you to leave.

” Castellano’s gaze shifted from the headstones to the admiral. He studied the man for a moment, the perfectly pressed uniform, the chest heavy with ribbons that spoke more of desk assignments than combat, the soft hands that had never gripped a rifle in anger. When he spoke, his voice was quiet, a low rumble like distant thunder.

“I served with General Richards. Thought I’d pay my respects.” Hail let out a short, humorless laugh. A few of the younger officers standing nearby glanced over, curious about the confrontation unfolding at the edge of the ceremony. The admiral’s confidence swelled with the attention. “You served with General Richards,” Hail repeated, his tone dripping with skepticism.

“Really? And in what capacity would that be? Grounds keeper motorpool. He looked Castiano up and down, his lip curling slightly. You don’t look like officer material. Hell, you don’t even look like you could pass a PFT. The insult hung in the air. A few of the officers shifted uncomfortably. One, a young captain with a combat action ribbon felt something twist in his gut.

There was something wrong about this. something profoundly disrespectful in the way the admiral was treating this old man. The captain had seen enough combat to recognize a certain quality in veterans who’d been through the worst of it. A stillness, a weight, this old man had it in spades. Castano didn’t flinch. He’d been underestimated his entire life.

It was a role he’d learned to wear like camouflage. I wasn’t an officer, he said simply. Just did my job. Your job? Hail scoffed. He turned slightly, playing to his small audience. Now, “Let me guess. Supply clerk, admin.” Hepaused, his eyes lighting up with cruel amusement. “Oh, I know. You were one of those guys who tells war stories at the VFW.

Big tales about missions that never happened, right?” The captain felt his jaw tighten. This was crossing a line. But Hail was a rear admiral. You didn’t interrupt a rear admiral. Castellano remained silent, his expression unchanged. He’d learned long ago that some men needed to talk themselves into corners before they understood their mistake.

Hail took another step closer, invading the old man’s space with the casual arrogance of someone who’d never been truly challenged. You know what I think? I think you read General Richard’s obituary in the paper and decided to crash his funeral for the free coffee and cookies. His voice dropped to a mock confidential whisper, though still loud enough for others to hear. “It’s pathetic, really.

Stolen valor is a federal offense. Old-timer. Never claimed any valor,” Castellano said quietly. “Just wanted to say goodbye to a friend.” “A friend,” Hail repeated, his voice rising now. “General Richards was a twostar. He commanded me. He advised the joint chiefs. He didn’t have time for He waved his hand dismissively at Castayano’s worn suit.

Whatever you are. The captain couldn’t stay silent anymore. He stepped forward, his voice respectful but firm. Admiral, sir, perhaps we should, Captain. Hail snapped, not even looking at him. I don’t recall asking for your input. Return to your position. The captain’s mouth closed. He stepped back, but his eyes remained on the old man trying to place him.

Something nagged at the edge of his memory. A story his Gunny had told him years ago. About operators who didn’t exist on paper, about missions that never made the news. About men with call signs instead of ranks. Hail turned his full attention back to Castellano. You want to convince me you knew General Richards? Fine.

What unit did you serve in? Can’t say, Castellano replied. Hails eyebrows shot up. Can’t say. Oh, that’s convenient. Let me guess. Classified, right? Super secret squirrel stuff. He laughed again, louder this time. A few of the politicians near the tent glanced over, annoyed by the disturbance. You know what? I’ve dealt with enough wannabes to spot one a mile away.

You probably never even served. I served, Castiano said, his voice still level, still quiet. Then show me some proof. Where’s your DD214? your unit patch. Hell, do you even have a call sign or did you just drive a truck somewhere safe while real Marines did the fighting? The question hung in the air.

For a long moment, Castiano said nothing. Then, with the same quiet calm he’d maintained throughout the entire confrontation, he answered, “Payback.” The word was simple, one word. But something about the way he said it, the weight behind it, the history compressed into those three syllables, made the captain’s breath catch.

Hail stared at him, then burst out laughing. It was a loud, performative laugh, the kind designed to humiliate. Payback. Oh, that’s rich. That’s really rich. He turned to the other officers, gesturing at Castayano like he was a circus act. Gentlemen, we have a real badass here. Call sign a payback. What’s next? Rambo. Terminator.

Several of the younger officers chuckled nervously, more from obligation than genuine amusement. But the captain didn’t laugh. He was staring at Castiano now, his mind racing. Payback. He’d heard that name before. Where had he heard that name? Hail wasn’t done. He stepped even closer, his face inches from Castanos, his breath hot and coffee stale.

You want to know what I think? Payback? I think you’re a sad old man living in a fantasy. I think you’ve been telling these stories so long you actually believe them. He reached out suddenly, his hand brushing against something in Castiano’s suit pocket, his fingers closed around it, pulling it out. What’s this? Your good luck charm? It was a dog tag, but not a standard issue one.

It was bent, misshapen, the metal dark with age and something else. Rustcoled stains that could only be dried blood. The embossed letters were still barely visible. Kowalsski James M. Hail held it up to the light, his lip curling in disgust. This is trash. Literal garbage. He dangled it between two fingers like a dead rat.

You carry this junk around and expect people to take you seriously. The moment his thumb pressed against the bloodcrusted metal, everything changed. The manicured lawns of Quantico vanished. The white headstones, the flag draped casket, the dress blues and polished shoes. All of it melted away like smoke in a strong wind. The temperature surged from the cool Virginia spring to the suffocating dry heat of the Middle East.

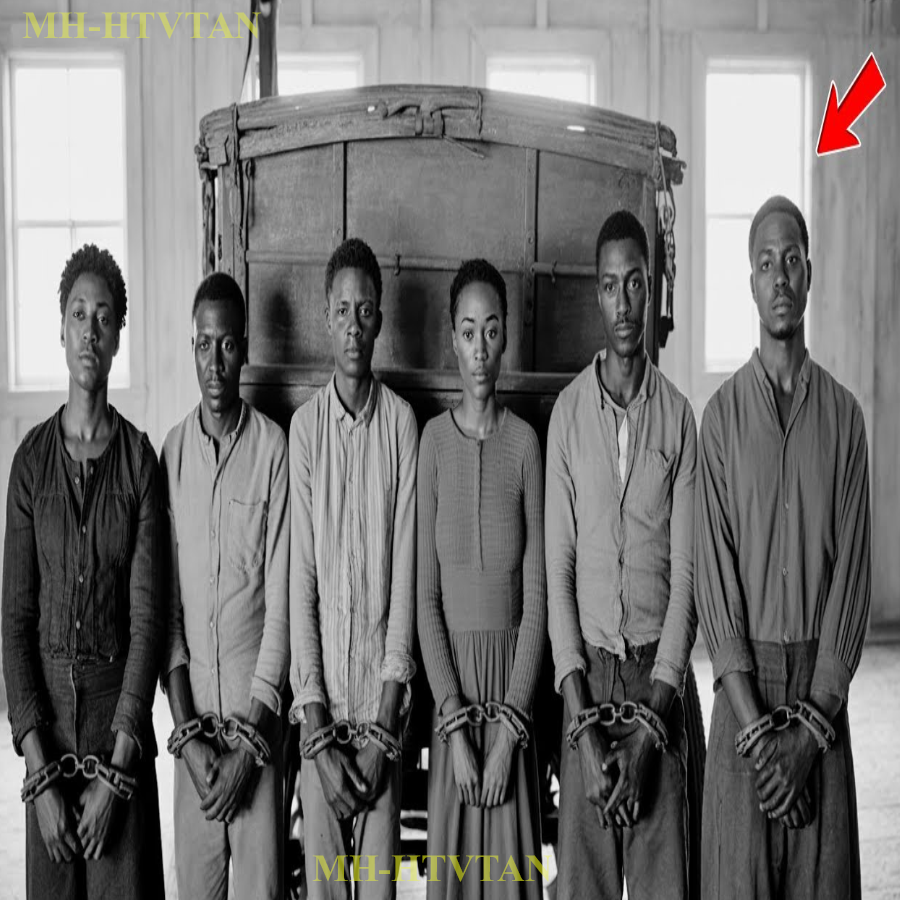

The scent of fresh cut grass was replaced by the acrid stench of burning rubber, cordite, and decay. Frank Castayano was 33 years old again. The suit was gone, replaced by black fatingsues and tactical gear stripped of any identifying marks. He stood in the shattered remains of aBayroot street. October 1983, 5 days after the barracks bombing that had killed 241 Marines.

This was October 12th there in 1983. 5 days since the truck bomb had torn through the Marine barracks at Beirut International Airport. 241 dead, the largest single day loss of Marine life since Ewima. The world was still reeling. Politicians were making speeches. Diplomats were scrambling. And six Marines who’d been on a reconnaissance patrol when the bomb went off had been captured by a Hezbollah splinter group looking to maximize the propaganda value of America’s grief.

The official position regrettable but rescue is not viable. Risk of international incident too high. Negotiations ongoing. Translation: They’re already dead. We just haven’t acknowledged it yet. Castellano had been in a safe house in Cyprus when the call came through. Not through official channels.

Those didn’t exist for men like him. It came from a colonel he’d worked with in El Salvador. A man who understood that sometimes the right thing to do and the legal thing to do were separated by an ocean of red tape and political cowardice. Six Marines Frank captured. Hezbollah fortress in Hyel Selum district. Triple reinforced. 12 guards minimum.

Civilian shields everywhere. State Department says no go. Pentagon says impossible. A pause. I say you’re the only man who could pull it off. When do I leave? Castano had asked. Not if. When? Now he was here. Dressed in black fatingsues with no tags, no insignia, nothing that could tie him back to the United States.

If this went sideways, his gear was clean. All serial numbers filed off. All traceable elements removed. If he died tonight, he’d be an unidentified mercenary, a criminal element, a regrettable footnote that would vanish into the chaos of a war torn city. The building ahead was a three-story structure that had once been apartments.

Now it was a fortress. Sandbags stacked at every window, barbed wire coiled across the rooftop, a single entrance facing the street, heavily guarded. But Castiano had spent two days surveilling the location, watching patterns, counting heads, timing guard rotations. He knew their schedule better than they did.

He also knew about the sewer access point. Beirut’s infrastructure was a mess. Ancient Roman tunnels mixed with Ottoman era construction, all of it crumbling and unmapped. But Castayano had found a local who’d been willing to talk for the right amount of cash. There was a drainage tunnel that ran beneath the building, flooded with sewage, cramped, pitch black, but it led to a maintenance access in the basement.

Castellano checked his watch. 0247 hours. Guard change in 13 minutes. That was his window. He moved through the shadows like smoke, crossing the debris strewn street in a low crouch. His boots made no sound. Years of training had taught him how to distribute his weight, how to read terrain, how to become part of the darkness.

He reached the sewer great, pried it open with a small crowbar, and descended into hell. The smell was overwhelming. Raw sewage, decomposition, chemicals. The tunnel was barely 4 ft high, forcing him to crouch walk through kneedeep filth. Water rats scattered as his NVGs illuminated the tunnel in shades of green. His rifle was slung across his back, waterproofed in a plastic bag.

In his hands, just the suppressed Beretta. 50 m. The tunnel seemed to stretch forever. His knees burned. His lungs protested the toxic air. But he kept moving, one step at a time. Because somewhere above him were six Marines who deserved better than a politician’s eulogy and a [clears throat] flag draped coffin. He reached the maintenance access.

a rusted ladder leading up to a hatch. He paused, listening, footsteps above. Two men moving slowly. Castiano waited, counting seconds. The footsteps faded. He pushed the hatch open slowly, wincing at the metal-on-metal scrape and hauled himself up into the basement. It was dark. Concrete floor, exposed pipes, crates of supplies stacked against the walls.

He unwrapped his rifle, checked the magazine, chambered around. The suppressor was already attached. Intel said the Marines were being held on the second floor. That meant navigating two floors of enemy territory without being detected. He moved to the stairwell, his back pressed to the wall, his breathing shallow.

He could hear them now, voices from above, speaking in Arabic. He ascended the stairs like a ghost. Each footfall placed with surgical precision. First floor empty, or at least the hallway was. Voices came from a room to his left. Cigarette smoke drifting under the door. He bypassed it, continued upward. Second floor. This was it. The hallway was dim, lit by a single bare bulb.

Two guards stood outside a door at the far end, smoking and talking in low voices. Their rifles were slung casually over their shoulders. They weren’t expecting trouble. Castayano raised his rifle. The first guard went down with a suppressed 556 round through the temple,his body crumpling silently. The second guard had just enough time to register his partner falling before the second round punched through his forehead.

Both bodies hit the floor with dull thuds. Castiano was moving before they finished falling. He grabbed the first guard’s body, dragged it into a nearby room, then repeated with the second. 10 seconds. That’s all he had before someone noticed the guards were missing. He reached the door. Locked. He pulled a set of picks from his vest.

Worked the mechanism. It clicked open. He pushed the door inward, rifle up, finger on the trigger. The room smelled like blood and fear. Six Marines. They were in bad shape. Two were unconscious, their faces swollen from beatings. One had a leg bent at an unnatural angle, broken. Another had burns on his arms. The remaining two were alert, their eyes widening as Castayano stepped into the room.

One of them, a young lieutenant with blood crusted in his hair, started to speak. Castano put a finger to his lips. Silence. He moved quickly, cutting their restraints with his knife. The lieutenant leaned close, whispering. Who the hell are you? Payback. Castiano replied. Can you walk? The lieutenant nodded. Three of us can.

The others, he glanced at the two unconscious Marines, the one with the broken leg. I’ll carry them, Castiano said. It wasn’t a question. That’s suicide, the lieutenant hissed. There’s 12 guards in this building. There’s 10 now, Castiano corrected. and we’re leaving now. The reality of extraction set in fast. Castellano made a tactical decision.

He’d carry two at once on his back in a fireman’s carry, using webbing to secure them. The third, the one with the broken leg, would have to be supported by the others. They moved into the hallway. Castellano took point. The two unconscious Marines lashed to his back, their combined weight nearly 200 lb.

His knees screamed, his spine compressed, but he kept moving. They made it to the stairwell. That’s when the alarm went up. Someone had found the dead guards. Shouts erupted from the third floor. Boots thundered on stairs. Castellaniano shoved the lieutenant forward. “Go. Basement sewers. I’ll cover. We’re not leaving you. That’s an order.

” Castellano barked. He turned, dropped to one knee, and opened fire. The stairwell became a killbox. Guards poured down from the third floor and ran straight into suppressed gunfire. Three went down immediately. The others scrambled for cover, returning fire wildly. Rounds sparked off concrete, punched through drywall.

Castellano took a round to his vest. Felt like getting hit by a sledgehammer. He kept firing. He burned through two magazines in 30 seconds. The stairwell was chaos. muzzle flashes, screaming, the wet smack of bullets hitting flesh. When there was a lull, he retreated, moving backward down the stairs while reloading. He hit the basement.

The Marines were already in the sewer tunnel, moving as fast as they could. Castellano followed, pulling the hatch shut behind him and jamming it with a steel rod. The tunnel was worse with seven men. They moved in a chaotic shuffle, wounded men groaning, everyone slipping in the filth, the sound of boots splashing echoing off the walls.

Above them, they could hear the guards trying to force the hatch. Gunfire punched through the metal, rounds ricocheting off stone. “Move! Move!” Castiano shouted. They reached the exit grate. He shoved it open, helped haul the Marines up one by one. The street was chaos now. Vehicles racing toward the building, spotlights sweeping.

Castiano keyed his radio. Blackbird, this is payback. Package secured. Need immediate extract. Grid delta 7. The response was crackling static. Then payback. Blackbird inbound. 30 seconds. Mark your position. Castellano pulled an IR strobe from his vest, activated it. He heard the helicopter before he saw it.

A blacked out UH60, no markings, flying nap of the earth. It flared over their position, the crew chief waving them aboard. They loaded the wounded first. The lieutenant was next. Castiano was last, providing cover fire as guards rounded the corner. He emptied his last magazine, dropped the rifle, and leaped for the helicopter’s skid.

Hands grabbed him, hauled him aboard. The helicopter banked hard, pulling away as tracers lit up the night sky. Inside the helicopter, the lieutenant collapsed against the bulkhead, breathing hard. He looked at Castano. This nameless, blood soaked operator who just walked into hell and dragged them out. “Who sent you?” “Nobody,” Castiano said.

“Officially, I was never here. Neither were you.” The lieutenant nodded slowly. Then he reached up, pulled his dog tags over his head. They were covered in his own blood from a gash on his scalp. He pressed them into Castellano’s hand. This is all I have, brother. I owe you my life. Castellano looked down at the dog tags.

Kowalsski James M. He met the lieutenant’s eyes, saw the gratitude, the debt that could never truly berepaid. He closed his fist around the metal. You don’t owe me anything. Just live a good life. That’s payment enough. The helicopter climbed into the night, leaving Beirut behind. In the building they just escaped, Hezbollah fighters found something painted on the basement wall in Arabic, written in the blood of their own men. Debts paid in full.

The memory shattered like glass. Frank Castiano blinked. The heat of Beirut dissolved. The roar of the helicopter faded into silence. He was 74 again, standing in Quanico National Cemetery, the dog tags pressed against his palm. Admiral Hail was still holding the tags, still sneering, oblivious to the war that had just played out in Castayano’s mind.

Seriously, you collect garbage like this. What’s next? a participation trophy from. He didn’t get to finish because through the quiet of the cemetery, cutting through the bird song and hushed conversations, came a sound that made every Marine in attendance straighten instinctively. The rumble of heavy engines, the crunch of tires on gravel, the unmistakable approach of a motorcade moving with purpose.

Four black Chevy Suburbans crested the hill, their windows tinted, their government plates gleaming in the sun. They screeched to a halt at the cemetery entrance, doors flying open before the vehicles had fully stopped. Men emerged, Marines in dress blues, their chests heavy with ribbons, their faces grim, and from the lead vehicle, stepping out with the deliberate authority of a man who’d commanded thousands, came a figure that made Admiral Hail’s breath catch in his throat.

General James Kowalsski, retired commandant of the Marine Corps, silver hair, ramrod straight posture, and eyes that had seen war and remembered every lesson. He scanned the crowd, his gaze sweeping past the politicians, the junior officers, the family members, until his eyes locked on Frank Castayano, and his entire expression changed.

The hard command presence softened into something else, something like reverence. Kowalsski began walking, his polished shoes marking a steady rhythm on the cemetery path. He walked past Admiral Hail without a glance, past the other officers, past everyone. His path led to one man and one man only. He stopped 3 ft in front of Castiano.

And then with the precision of a man who’d spent 50 years perfecting the movement, “General James Kowalsski rendered the sharpest, most perfect salute Frank Castayano had ever received.” “Mr. Castayano,” Kowalsski said, his voice carrying across the silent cemetery. “It’s been a long time. Payback.

” The silence that followed was absolute. It was the kind of silence that descends when the world realigns itself. When everything people thought they understood suddenly shifts into a new and humbling configuration. Admiral Hail stood frozen, the bloodstained dog tag still dangling from his fingers. His mouth hung slightly open, his face rapidly draining of color.

Around him, the other officers had gone rigid, their attention snapping to the scene unfolding before them. Frank Castaniano looked at the general at James Kowalsski, the young lieutenant he’d carried out of Beirut 41 years ago. The boy had become a man. The man had become a legend in his own right, but the eyes were the same.

“Grateful, haunted,” Castayano’s hand moved slowly, returning the salute with quiet dignity. “General,” he said simply. “Good to see you’re still breathing.” Kowalsski lowered his hand, but his gaze never wavered. Because of you, sir. Because of you. He turned then, his eyes sweeping across the assembled crowd. When he spoke again, his voice carried the full weight of command.

For those of you who don’t know, Kowalsski began, let me tell you who you’re looking at. You see an old man in a worn suit. I see a giant. This is Frank Castano. To the history books, that name means nothing. The operations he conducted don’t exist in any official record. But to six Marines who were left for dead in Beirut in October of 1983.

He is the reason we’re alive. A murmur rippled through the crowd. Kowalsski continued, his voice rising with controlled passion. After the barracks bombing in Beirut, six of us were on a patrol when we were ambushed and captured. Hezbollah militants. We were held in a fortified building in Hail Salum. We were beaten, tortured, and officially we were expendable.

The State Department said a rescue was diplomatically impossible. The Pentagon said it was tactically unfeasible. Our own government wrote us off. He paused, letting that sink in. But there are men in this world who don’t accept those answers. Men who understand that when you put on this uniform, you make a promise. Not to politicians, not to diplomats, but to the marine next to you.

Frank Castayano made that promise mean something. He gestured toward Castayano. This man calls sign payback infiltrated a heavily fortified Hezbollah stronghold. Alone, he went through a sewer system, breached the building, neutralized 12 hostilecombatants, and extracted all six of us. Two of us were unconscious, one had a broken leg.

He carried us out on his back while providing suppressive fire. And when he left that building, he painted a message on the wall in the blood of the men who’d tortured us. Debts paid in full. The crowd was completely still now. Every eye was on Castiano, seeing him not as a confused old man, but as something else entirely, a legend made flesh.

Kowalsski turned his attention to Admiral Hail, who looked like he wanted the earth to swallow him whole. The general’s expression was ice. Admiral, you asked about this man’s credentials. You mocked his call sign. You called his most precious possession garbage. Hail’s mouth opened, but no sound came out. Kowalsski took a step toward him.

Those dog tags you’re holding, those are mine. Covered in my blood from the night I was captured. Frank Castayano refused every medal the court tried to give him. He refused recognition. He refused promotion. The only thing he ever accepted was this, a bloodstained piece of metal from a 24-year-old lieutenant who owed him everything.

The general reached out, gently taking the dog tags from Hail’s nerveless fingers. He held them up to the light, and several people gasped. In the sunlight, the rust brown stains were clearly visible. Kowalsski handed them back to Castayano with reverence. “You demanded proof of service, Admiral,” Kowalsski said coldly. There’s your proof.

This man has done more for the Marine Corps in a single night than most of us will do in entire careers. Around the cemetery, something remarkable was happening. One by one, the Marines in attendance began raising their hands in salute. Not to Kowalsski, to Castayano. A colonel with a chest full of ribbons saluted.

A sergeant major who’d served in Desert Storm saluted. Even the young captain snapped to attention and rendered honors. Castellano stood quietly, accepting their respect with humble dignity. He didn’t smile. He didn’t grandstand. He simply nodded, acknowledging their gesture. Kowalsski turned back to Hail. Admiral, you have disgraced yourself today.

You stood in a place dedicated to honoring those who served, and you showed contempt for a man whose service puts us all to shame. You mistook humility for weakness. You confuse the absence of medals for the absence of merit. Hail finally found his voice, though it came out as a strangled whisper. General, I I didn’t know.

I had no idea. That’s precisely the problem. Kowalsski cut him off. You didn’t know and you didn’t care to find out. You saw an old man in a cheap suit and made assumptions. Before Kowalsski could continue, a weathered hand touched his arm. Castiano had stepped forward, his expression calm. Jim, he said quietly. Let it go. Kowalsski turned surprised.

“Frank, he disrespected you. He He didn’t know,” Castellano said simply. “He looked at Hail, and there was no anger in his eyes, just weary understanding.” “Admiral, you made a mistake. We all make them. The measure of a man isn’t whether he makes mistakes. It’s what he does.” After he stepped closer to Hail, “Those stars on your shoulders don’t automatically grant you respect.

They’re a responsibility, a promise that you’ll lead with wisdom, humility, and care for the people under your command. Respect isn’t taken. It’s earned every single day.” Hail’s eyes were glistening. He nodded slowly, unable to speak. Castano reached out and placed a hand on the admiral’s shoulder. You’re a good Marine, son. I can see it.

You just forgot for a moment what that means. Don’t let this define you. Let it teach you. The gesture broke something. Inhale. A tear tracked down his cheek. He stood at attention. Mr. Castayano, I I’m sorry. Truly, I know you are. Castano turned to Kowalsski. General, I think we’ve disrupted this funeral enough.

General Richards deserves better. Kowalsski nodded. You’re right. Please, Frank, join us. As Castiano walked toward the chairs, the crowd parted. People reached out to shake his hand, to touch his shoulder. The widow of General Richards took both his hands and hers. “Your payback,” she said. Andrew talked about you. He said you were the standard, the man every Marine should aspire to be.

Andrew was a good man. I’m sorry for your loss. Thank you for coming. It means more than you know. The funeral concluded with full military honors. A seven gun salute cracked across the cemetery. The honor guard folded the flag with mechanical precision. When the widow received the triangle of stars and stripes, she clutched it to her chest and wept quietly.

As the crowd began to disperse, Admiral Hail approached Castayano slowly. He came to attention. Mr. Castayano, I don’t expect forgiveness. What I did was inexcusable, but I want you to know that I will spend the rest of my career trying to be worthy of the uniform I wear. Castano stood and extended his hand. Hail took it. You’re a good man, Admiral.

Don’t let one mistake define you. Use it. Learn fromit. And when you see someone who doesn’t look like they belong, remember today. Hail saluted, not casually, but a salute that meant something. Castano returned it and Hail walked away, his shoulders straighter. In the weeks that followed, the story spread through the Marine Corps like wildfire.

Admiral Hail reported to HQMC, expecting relief of command. Instead, he was assigned to help develop a new training program, the Castayano Doctrine, a mandatory course for all officers being considered for flag rank, focused on leadership, humility, and ethical responsibilities of command. Hail threw himself into the program with the zeal of a convert.

He interviewed every surviving member of the Bayrooe extraction, traveled to Walter Reed to meet Marines rescued and other forgotten operations, and spent hours with retired sergeants major. He became obsessively dedicated to getting it right. 8 months later, on a cold Saturday morning in February, Hail found himself in a diner just outside Quantico.

The bell above the door chimed. Frank Castiano walked in, shaking rain from his jacket. Hail’s heart hammered. He stood, walked to the counter, and sat two stools away. Admiral Castayano nodded. Mr. Castayano. For a long moment, neither man spoke. Finally, Hail pulled out a $20 bill and placed it on the counter for the coffee and for the lesson.

How’s the doctrine coming along? It’s good. Really good. We’ve put over 200 officers through it. The feedback has been humbling. A lot of senior leaders are realizing they’ve made the same mistakes I did. He paused. We’re making a difference on sir because of you. Not because of me, son. Because you chose to learn instead of making excuses. That takes courage, too.

They sat in companionable silence. Eventually, Hail stood to leave. He extended his hand. If you ever need anything, sir, anything at all, you call me. I mean that. Castano shook his hand. I know you do. Stay safe, Admiral, and keep teaching. Frank Castaniano finished his coffee, paid his bill, and walked back out into the rain.

He climbed into his old Ford truck and headed home. He had groceries to buy, a lawn to mow, a quiet life to live. He was just an old man in a worn jacket. But to six Marines who’d walked out of Beirut alive. To hundreds of officers learning what true leadership meant. And to one admiral who’d been given a second chance, he was so much more. He was payback.