In the winter of 1840, a traveling physician named Dr. Samuel Witmore stumbles upon an isolated homestead in the Appalachian Mountains of Virginia, where he discovers the Harlow family, a clan that has lived in complete isolation for three generations. Practicing inbreeding to keep their bloodline pure, what begins as a medical investigation becomes a descent into psychological horror as Dr.

Whitmore uncovers the family’s twisted rituals, their disturbing beliefs about purity and corruption, and a shocking secret that challenges everything he believes about human nature and morality. The thing that should disturb you most about the Harlow clan isn’t what you think it is.

It isn’t the physical deformities, the practiced isolation, or even the generations of inbreeding that created them. What should truly unsettle you is how long they existed before anyone knew, how deliberately they chose their fate, and what Dr. Samuel Witmore found in that cellar on February 14th, 1840. A discovery so profoundly wrong that it would remain sealed in medical archives for over a century, too dangerous for public knowledge.

Dr. Samuel Witmore was not supposed to be in the Virginia mountains that winter. The 42-year-old physician had built a respectable practice in Richmond, treating politicians and merchants, attending balls and social gatherings befitting a man of his station. But his younger brother Thomas had gone missing three months prior while surveying timber claims in the Appalachian frontier, and Samuel had exhausted every official channel trying to locate him.

The local magistrate had been sympathetic but unhelpful. Men vanished in those mountains with disturbing regularity, consumed by the wilderness, murdered by bandits, or simply swallowed by the vast and indifferent forest. Winter had arrived early that year, and the search parties had turned back weeks ago, declaring Thomas lost to the mountain.

Samuel refused to accept this conclusion. On February 9th, 1840, he departed Richmond with a hired guide named Jacob Stern, a weatherworn frontiersman who claimed to know every hollow and ridge in the region. They brought three pack horses loaded with supplies, medical equipment, and enough provisions for 2 weeks.

Samuel’s wife, Catherine, had begged him not to go, clutching their six-year-old daughter, Mary, while tears streamed down her face. But Samuel had made a promise to their mother before she died. He would always protect Thomas, always bring him home. He kissed Catherine goodbye, mounted his horse, and rode west into the gray morning, not knowing he was riding towards something far worse than his brother’s death.

The first week passed in brutal monotony. They followed old hunting paths and logging trails, stopping at scattered homesteads to ask about Thomas. Most frontier families were suspicious of outsiders, answering questions with curt nods or hostile silence. Those who did speak confirmed that a man matching Thomas’s description had passed through in November, heading deeper into the mountains with his surveying equipment, but no one had seen him return.

The trail grew colder with each passing day, both literally and figuratively. Temperatures plummeted and snow began falling in thick, heavy sheets that obscured the path ahead. On the eighth day, Jacob Stern announced they needed to turn back. The snow was now knee deep. Their supplies were dwindling, and continuing forward would be suicide.

Samuel pleaded for one more day, just one more ridge to search. Jacob reluctantly agreed, but his expression made it clear this would be the last extension. They pressed on through the afternoon, climbing a steep mountain slope that seemed to rise forever into the white sky. Samuel’s hands were numb inside his gloves, his face raar from the biting wind.

He was beginning to accept that Catherine had been right, that this journey was folly, that Thomas was truly gone. Then Jacob’s horse stopped. The animal refused to continue, stamping nervously and snorting clouds of steam into the frozen air. Jacob dismounted and examined the ground, his weathered face creasing with confusion.

Samuel climbed down from his own horse and joined him. There, partially obscured by fresh snow, was a trail, not a deer path or natural formation, but a deliberately cleared trail wide enough for a cart. Fresh wagon tracks were still visible in the snow, meaning someone had passed this way within the last few hours. But that was impossible.

They were miles from any known settlement, high in a region Jacob had sworn was uninhabited wilderness. “This ain’t right,” Jacob muttered, his hand instinctively moving to the rifle slung across his back. “Nobody lives up here. Land’s too poor. Winter’s too hard. And I’ve been hunting these mountains for 20 years. Never seen this trail before.

” Samuel felt a flutter of hope mixed with apprehension. If someone lived here, they might have seen Thomas. They might know what happened to him. Heinsisted they follow the trail, despite Jacob’s visible reluctance. The guide finally nodded, but kept his rifle ready, his eyes scanning the treeine with the weariness of a man who had learned to trust his instincts.

The trail wound through dense pine forest, the snowladen branches, creating a tunnel of white that muffled all sound. The silence was absolute and unnatural. No bird calls, no wind rustling through the trees, not even the distant crack of ice burdened branches breaking under their load.

Just the crunch of their boots in the snow and the labored breathing of their horses. Samuel’s medical training had taught him to observe details, and he noticed something odd about the trees flanking the trail. Many of them bore strange markings, deep gouges carved into the bark in patterns that seemed almost deliberate, symbols perhaps, though in no alphabet Samuel recognized.

They had been following the trail for nearly an hour, when the forest suddenly opened into a clearing. What Samuel saw there made him stop breathing. In the center of the clearing stood a large homestead, but Homestead felt inadequate to describe the structure. It was massive, built from dark timber that seemed to absorb rather than reflect light, with a steep roof designed to shed heavy snow, two stories tall with multiple additions that sprawled in seemingly random directions, as if the building had grown organically over many years. Smoke rose

from three separate chimneys, but there was no other sign of life. No animals in the corral, no movement in the windows, no sounds except that oppressive, suffocating silence. What truly disturbed Samuel, what made his physician’s mind recoil, was the smell, even in the freezing air, even with his nose half-numb from cold.

He could detect it, a sweet, rotten odor that reminded him of the charity hospital back in Richmond, where the poorest patients languished in overcrowded wards with insufficient ventilation. It was the smell of sickness, of bodies failing, of something fundamentally wrong with human flesh. Jacob had noticed it too, his face pale beneath his beard.

“We should go back,” he whispered. “Right now, whatever’s in there, it ain’t natural.” But Samuel saw curtains moving in one of the downstairs windows, saw a pale face watching them. Someone was alive in there, someone who might need medical help. He was a physician. He had taken an oath. He dismounted and approached the house, his medical bag clutched in his gloved hands.

Jacob cursed under his breath, but followed, keeping his rifle raised. As they drew closer, Samuel could see that the house’s exterior was decorated with more of those strange symbols carved deep into the wooden walls and doorframe. They appeared to be words, but in a language that predated anything Samuel had studied. The letters were angular and primitive, like something scratched by ancient peoples in cave walls.

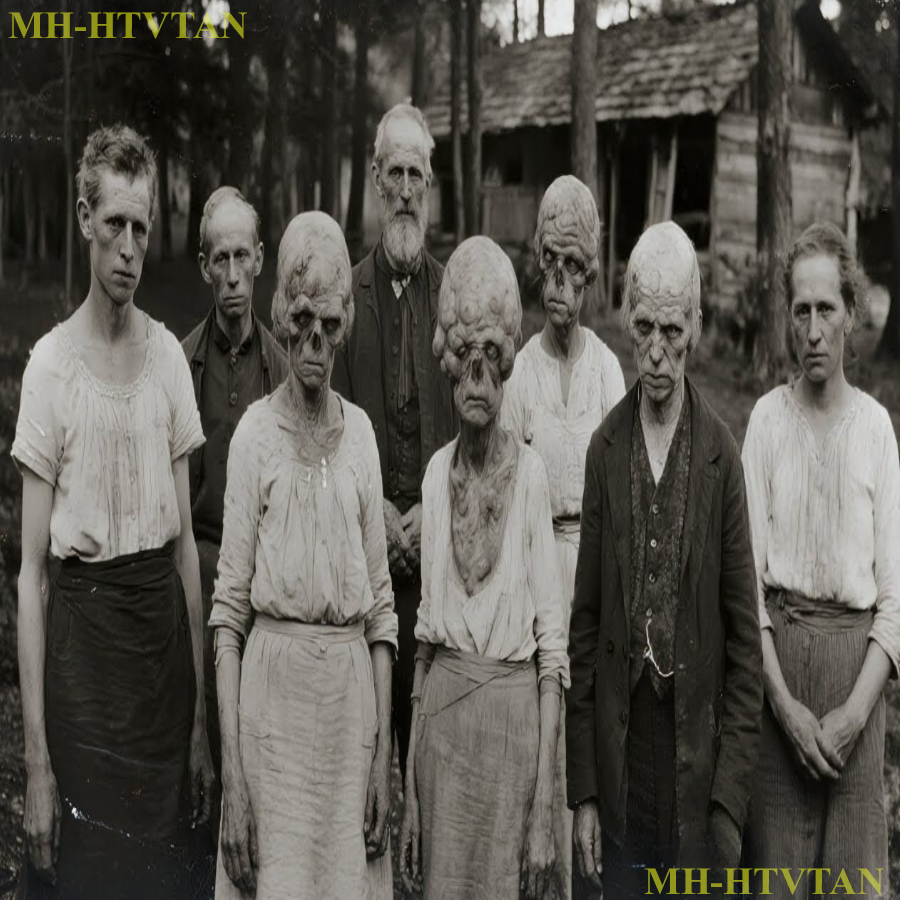

Samuel knocked on the heavy wooden door. The sound echoed strangely, as if the house was mostly hollow inside. For a long moment, nothing happened. Then the door opened just a crack, and Samuel found himself staring into the most disturbing face he had ever seen. It was a young woman, perhaps 20 years old, but her features were wrong in ways that made his medical training scream warnings.

Her eyes were too far apart, set at angles that shouldn’t be possible in a human skull. Her lower jaw protruded significantly, forcing her mouth into a permanent grimace that revealed malformed teeth. One of her ears was missing entirely, leaving just a small hole in the side of her head. But worst of all was her expression.

She was smiling at them, delighted, as if their arrival was the most wonderful thing that had ever happened. visitors,” she said, her voice thick and slurred from her malformed mouth. “Papa will be so pleased. We never get visitors. Please, please come inside. It’s cold. You must be cold.” Papa says, “Cold is the enemy.

The cold tries to corrupt the blood. Come inside where it’s warm.” She opened the door wider, revealing herself fully. She was heavily pregnant, her belly grotesqually swollen beneath a stained dress that might have once been white. Samuel’s physician instincts wared with his growing horror. This woman needed medical attention desperately, but every other sense was screaming at him to run, to get back on his horse, and ride until this place was far behind him. He stepped inside.

God help him. He stepped inside. Jacob followed, though Samuel heard him chamber around in his rifle. The interior of the house was dim, lit by oil lamps that cast dancing shadows on walls covered with more of those strange symbols. The smell was much worse inside. That sweet rot mixed with unwashed bodies, old food, and something else Samuel couldn’t identify, but which made his stomach clench.

The woman led them through a narrow hallway, her gate awkward and shuffling. Samuel noticed that her left leg was significantlyshorter than her right, forcing her to lean heavily with each step. They emerged into what appeared to be a common room, and Samuel’s breath caught in his throat. There were people everywhere, perhaps 15 or 20 of them, all crowded into the space, and all turning to stare at the newcomers with expressions ranging from vacant curiosity to disturbing intensity.

and every single one of them bore visible signs of severe genetic defects. A boy of perhaps 10 years sat in the corner, but his head was misshapen, far too large for his thin body, and his eyes didn’t focus on anything. An elderly woman rocked in a chair, her spine twisted into an S-curve so severe she was nearly folded in half.

Two young men, who might have been twins, stood near the fireplace, but their faces were nearly identical nightmares. Cleft pallets so severe their entire upper lips were split, revealing gums and malformed teeth. But what froze Samuel’s blood was the realization that despite their varied ages and deformities, they all shared certain unmistakable features.

The same distinctive nose shape, the same unusually colored eyes, a pale amber that seemed to glow in the lamplight, the same high prominent cheekbones. They were all related clearly and undeniably. This wasn’t a collection of unfortunate individuals seeking refuge together. This was a family, a family that had been interbreeding for generations.

“Welcome,” said a voice from the shadows near the fireplace, and a man stepped forward into the light. Samuel would later write in his journal that this was the moment he should have run, should have grabbed Jacob and fled into the frozen wilderness. Consequences be damned. The man was perhaps 60 years old, tall and surprisingly robust compared to the others, though his face bore the unmistakable stamp of inbreeding.

The same prominent features, the same amber eyes, but sharper, more intelligent. He wore a black suit that might have been fashionable 40 years ago, now threadbear and stained. His long gray hair was pulled back in a queue, and his beard was neatly trimmed. He carried himself with an air of authority, of education that seemed impossibly out of place in this nightmare.

“My name is Ezekiel Harlow,” the man said, his voice cultured and clear, with only the slightest hint of the speech impediments that affected the others. And you, sir, unless I am very much mistaken, are a physician. I can tell by your bag and your bearing. How absolutely providential. My daughter Charity is due to deliver very soon, and we could use skilled hands.

He gestured toward the pregnant woman who had opened the door. Tell me, doctor, do you believe in providence? Do you believe that God guides worthy men to where they are most needed? Samuel found his voice, though it came out and uncertain. I am Dr. Samuel Whitmore from Richmond. My guide and I are searching for my brother Thomas, who went missing in these mountains 3 months ago.

We saw your trail and hoped you might have information. He forced himself to maintain professional composure to treat this like any other patient consultation. Even as his mind reeled at what he was seeing. But yes, I am a physician, and if your daughter needs assistance, I’m happy to provide it. Ezekiel Harlow’s smile widened, and Samuel noticed that unlike the others, his teeth were perfect, white and straight, and somehow more disturbing for their perfection amid so much deformity.

A physician searching for his lost brother. How very biblical. How very like Joseph seeking Benjamin. You are welcome here, Dr. Whitmore. You and your companion both. We have food and warm beds. It’s far too late to travel back down the mountain tonight. You’d freeze before you reach the treeine. Stay with us. Help my daughter. And in the morning, I will tell you everything I know about your brother.

Something in the way he said that last sentence made Samuel’s skin crawl. There was knowledge in those amber eyes. Some terrible secret. Jacob Stern pulled Samuel aside while the Harlow family prepared their evening meal, his calloused hand gripping the doctor’s arm with desperate strength. We leave at first light,” he hissed, his breath visible in the cold air of the narrow hallway where they stood.

“I don’t care what he says about your brother. These people, Christ Almighty, Samuel, look at them. This ain’t natural. This ain’t right. Something evil lives in this house.” Samuel wanted to agree. Wanted to give the order to saddle the horses immediately and ride into the frozen darkness. But he had seen the hope in Ezekiel Harlo’s eyes when he mentioned Thomas, and he had taken an oath as a physician.

Charity Harlow was perhaps a week from delivery, and given her obvious physical compromises, childbirth would likely kill her without proper medical intervention. He told Jacob they would stay the night, help the girl if needed, get information about Thomas, and leave at dawn. Jacob’s expression made it clear what he thought of thisplan, but he nodded curtly and moved his hand closer to his rifle.

Dinner was served in the main room around a massive oak table that looked handhune, its surface scarred by decades of use and marked with more of those strange symbols. The Harlo family gathered with an almost ritualistic precision, each member taking their assigned place without speaking. Samuel counted 22 people in total, ranging from Ezekiel himself down to a small boy of perhaps 3 years who sat in a high chair, drooling continuously and making soft muing sounds.

The food was surprisingly abundant. Roasted venison, root vegetables, fresh bread that steamed when broken open. Someone in this family was a capable cook, though Samuel found his appetite vanishing as he observed his dining companions more closely. The children especially disturbed him. There were nine of them, ranging from the toddler to what appeared to be a girl of about 16.

Every single one bore significant physical abnormalities. The 16-year-old girl whom Ezekiel introduced as Constants had eyes that didn’t align properly, one looking forward while the other drifted to the side, independent of her control. Her hands trembled constantly as she ate, and Samuel noticed that several of her fingers were fused together, creating flipper-like appendages.

A boy of perhaps 12 named Oadiah had legs so bowed he could barely walk, shuffling to the table with a gate that reminded Samuel of a crab’s sideways scuttle. His breathing was labored and wet, suggesting serious respiratory compromise. But what truly made Samuel’s medical mind real was the realization that these weren’t just random genetic misfortunes.

The pattern was too consistent, the defects too specific. This was the result of repeated sustained inbreeding over multiple generations. Something Samuel had only read about in medical texts documenting isolated European royal families or the results of brother sister marriages in ancient Egypt. He had never seen it on this scale, never witnessed the catastrophic genetic collapse that occurred when a family tree ceased to branch.

The harlows weren’t just inbred. They represented perhaps the most extreme case of human inbreeding ever documented in America. Possibly in the world, Ezekiel sat at the head of the table like a king presiding over his court, eating with surprising delicacy despite the primitive surroundings. He was clearly the patriarch in every sense, and every member of the family deferred to him with automatic, almost fearful obedience.

When he spoke, everyone else fell silent. When he gestured, people moved. Samuel noticed that the family members never made eye contact with Ezekiel. They would watch him from the corners of their eyes, tracking his movements, but would immediately look away if his gaze turned toward them. It was the behavior of prey animals monitoring a predator, and it set every one of Samuel’s instincts screaming.

You’re wondering about us, Ezekiel said suddenly, his amber eyes fixed on Samuel with unnerving intensity. About our condition, about how we came to be this way. I can see the questions in your face, doctor. You’re a man of science. You want to understand what you’re observing. He set down his fork and leaned back in his chair, steepling his fingers beneath his chin.

My family has lived on this mountain for three generations. Dr. Whitmore. We came here in 1767 when my grandfather Josiah Harlow brought his wife and three children into these mountains seeking religious freedom. He was a brilliant man, a scholar of the Bible and ancient texts, but his beliefs were not welcomed in civilized society.

The churches in Massachusetts called him a heretic. The magistrates threatened him with imprisonment. So he came here to the edge of the known world where he could worship God in the manner God had revealed to him. Samuel forced himself to eat a bite of venison, though it tasted like ash in his mouth. “And what manner was that?” he asked, knowing he shouldn’t engage, but unable to stop himself.

Jacob shot him a warning look from across the table, but Samuel ignored it. If he was going to help these people, if he was going to survive this night, he needed to understand what he was dealing with. Ezekiel’s smile returned. And again, Samuel was struck by how perfect his teeth were, how they seem to belong to a different face entirely. Purity, doctor.

My grandfather understood what modern churches have forgotten. That God demands purity above all else. The Bible tells us not to be unequally yolked with unbelievers, not to mix with the corrupt and sinful world. But my grandfather understood this meant more than mere spiritual separation. It meant blood separation, genetic purity.

He said those last words with reverent emphasis, as if they were sacred text. The world outside is corrupted, doctor. Every generation grows weaker, more diseased, more sinful. The blood is polluted by mixing, by allowing inferior lines to contaminate superior ones. Mygrandfather saw this truth and he acted upon it.

Samuel’s fork clattered against his plate. You’re saying your grandfather deliberately he couldn’t finish the sentence. Couldn’t give voice to the horror crystallizing in his mind. But Ezekiel had no such hesitation. Deliberately preserved our bloodline. Yes, he married his daughter Rebecca. Together they had five children including my father Nathaniel.

My father married his sister Ruth. They had eight children including myself and my three brothers. We married our sisters and our cousins. Always keeping the blood pure, always maintaining the line that God had chosen. This is the third generation of divine purity. Doctor, we are what humanity was meant to be before corruption entered the world.

He gestured around the table at his family, at the twisted bodies and malformed faces with something approaching pride. We bear the marks of our devotion. The world would call these deformities, but we know them for what they truly are, the price of purity, the sacred burden God places upon his chosen people.

The logic was so profoundly insane, so completely divorced from any rational understanding of biology or theology that Samuel simply stared in horror. This wasn’t ignorance or accidental harm. This was deliberate, systematic destruction of a family’s genetic health spanning 70 years done in the name of a twisted religious doctrine.

Ezekiel had been raised in this nightmare, taught from birth that the suffering around him was holy, that the genetic collapse destroying his family was divine will. The children, Samuel managed to say, his physician’s mind automatically moving to his primary concern, even through the horror, their suffering.

Many of them are in pain. The respiratory issues, the skeletal deformities, the neurological problems, these aren’t marks of divine favor. They’re the result of accumulated genetic damage. Without intervention, without introducing new bloodlines, your family will not survive another generation. He tried to keep his voice clinical, professional, even as his stomach churned.

Ezekiel’s expression didn’t change, but something flickered behind those amber eyes. something cold and terrible. Survival was never the goal, doctor. Purity is the goal. We are not meant to thrive in this world. This world is Satan’s domain, corrupted and fallen. We are meant to remain pure until God calls us home, until the final judgment when the pure shall be separated from the impure.

If we must suffer in this life, if our bodies must bear the burden of our devotion, then we suffer gladly. Every deformed child is a testament to our faith. Every early death is a martyrdom. The pregnant girl, Charity, spoke up from her place at the table, her malformed mouth struggling with the words.

I am blessed to carry Papa’s child, she said, one hand resting on her swollen belly. I will give him a pure son or daughter. Another generation of the chosen line. The implication of what she had just said hit Samuel like a physical blow. Papa’s child. Ezekiel had impregnated his own daughter. The baby she carried was the product of fatherdaughter incest, adding yet another layer of genetic catastrophe to an already compromised bloodline.

Samuel stood abruptly, his chair scraping loudly against the wooden floor. I need air, he said, his voice tight. Excuse me. He stumbled toward the door, desperate to escape the suffocating atmosphere of insanity. Jacob rose to follow him, but Ezekiel’s voice stopped them both. Before you go, doctor, you wanted to know about your brother, Thomas. The room fell silent.

Even the continuous drooling and soft muing sounds from the most severely affected family members seemed to stop. Samuel turned slowly, his heart hammering against his ribs. Ezekiel was still seated, but his posture had changed. He leaned forward now, his hands flat on the table, his amber eyes gleaming in the lamplight.

He came here, you know, 3 months ago, just as the first snows were beginning. He was surveying the timber, marking trees for harvest. He found our trail quite by accident, just as you did. Where is he? Samuel demanded, his voice breaking. Is he alive? Is he here? Ezekiel tilted his head, studying Samuel with the intensity of a naturalist examining an interesting specimen.

He was very kind, your brother, very sympathetic to our situation once he understood it. He stayed with us for several days, helping with repairs to the roof before winter truly set in. He was particularly good with the children. They adored him. Young Thomas was always laughing, always telling stories. He made this dark house brighter for a time.

The way Ezekiel spoke in past tense made Samuel’s blood run cold. What happened to him? Samuel’s hands were clenched into fists, his nails digging into his palms. Tell me what happened to my brother. Ezekiel stood moving around the table with surprising grace for a man his age. He stopped directly in front of Samuel, close enough thatSamuel could smell his breath.

mint leaves of all things, as if he’d been chewing them to freshen his mouth. Your brother made a choice, doctor, a profound choice. He saw our suffering, saw the pain my family endures in service of purity, and he offered a solution. He offered himself as a sacrifice to help us. Ezekiel’s hand moved to Samuel’s shoulder, gripping it with strength that bordered on painful.

He understood that we needed new blood, that without intervention the line would fail. But we couldn’t simply marry outside that would corrupt the purity. We needed someone who would give his blood willingly, who would become part of our sacred mission. Samuel’s vision was narrowing, the edges going dark as horror and understanding crashed over him. “What did you do?” he whispered.

We baptized him in the old way, Ezekiel said softly, almost tenderly. We brought him into the family properly. Three of my daughters, charity, constants, and faith, each took him as husband in the eyes of God. He gave them his seed so that new children could be born. Children with fresh blood to strengthen the line.

It was his gift to us, his sacrifice. And in return, we gave him the greatest gift of all. We made him pure. We showed him the truth of God’s plan. Samuel tried to pull away, but Ezekiel’s grip was iron. Where is he now? Samuel demanded again, though part of him already knew the answer, already understood the terrible truth.

He rests with the others, Ezekiel said, his voice still gentle, still calm. In the cellar, where all the family eventually goes, “He serves his purpose there, even in death. Nothing is wasted in God’s design, doctor. Every part has its place. Every sacrifice its meaning. He released Samuel’s shoulder and stepped back, his expression serene.

You’ll understand soon enough. You’re a man of learning like your brother. You’ll see the divine logic of what we do here. And perhaps, like Thomas, you’ll choose to help us willingly rather than resist the inevitable. The implied threat hung in the air like smoke. Samuel grabbed Jacob’s arm and pulled him toward the door, but Ezekiel’s voice followed them.

You won’t make it down the mountain tonight, doctor. The temperature has dropped 20° since you arrived. The horses can’t navigate the trail in darkness. They’ll break their legs or throw you into a ravine. You’ll stay. You’ll sleep in our guest room, and in the morning, I’ll show you where your brother rests.

Then you can make your choice. Help us willingly, or join Thomas in the cellar. The casual nature of the threat, delivered in that same calm, educated voice, was somehow more terrifying than any shouted warning could have been. Samuel and Jacob burst through the front door into the frigid night air. The temperature had indeed dropped catastrophically.

Samuel’s breath froze instantly, creating clouds of ice crystals. The horses were huddled together in the corral, their coats already rhymed with frost. Jacob was right. They couldn’t ride in this cold, in this darkness. They would die within an hour. Samuel looked at his guide, seeing his own horror reflected in Jacob’s weathered face.

They were trapped here, at least until dawn, in a house of madness with a family that had murdered his brother, and seemed perfectly willing to do the same to them. “We don’t sleep,” Jacob said quietly, his hand on his rifle. “We stay awake, stay armed, and the second there’s enough light to see the trail, we ride like hell.

itself is chasing us because it is Samuel. Whatever that man is, whatever this family has become, it ain’t human anymore. It’s something else, something wrong.” Samuel nodded mutely. His medical training, screaming that he should help these suffering people, while every survival instinct demanded he flee. They went back inside.

Staying in the cold meant certain death. But they took positions in the hallway near the front door, weapons ready, prepared to fight their way out if necessary. The night stretched ahead of them like a chasm, filled with the soft sounds of the Harlow family settling into sleep, the creek of old timber, and somewhere deep in the house, a rhythmic thumping that might have been machinery or might have been something else entirely.

Samuel thought of Thomas, of his brother’s body, lying in whatever nightmare the cellar contained, and felt tears freeze on his cheeks. He had come looking for answers, for closure. He had found something far worse, a glimpse into how far human beings could fall when faith divorced itself from reason. When purity became poison, when family became a prison of flesh and blood and bone, and the night was still young.

Samuel didn’t sleep. He sat with his back against the cold wall of the hallway, his medical bag clutched in his lap like a shield, watching the darkness beyond the dying lamplight and listening to the house breathe. Because that’s what it felt like. The structure itself seemed alive, expanding and contracting with each gustof wind, the ancient timber groaning like arthritic joints, the floors settling with sounds that resembled footsteps when no one was walking.

Jacob maintained his vigil by the front door, rifle across his knees, his eyes never closing for more than a few seconds at a time. They didn’t speak. What was there to say? They had stumbled into a nightmare, and dawn seemed impossibly far away. Around 2:00 in the morning, Samuel heard crying.

Not the wailing of an infant or the sobbing of an adult, but something in between. a keening animalistic sound that raised every hair on his neck. It was coming from somewhere above them, from the second floor where Ezekiel had said the children slept. The sound went on for perhaps 5 minutes, rising and falling in pitch, then abruptly stopped.

Samuel waited for some response from the adults, for Ezekiel or one of the mothers to go comfort whatever child was in distress, but no one came. The house returned to its previous sounds. Creaking timber, wind against shutters, that rhythmic thumping from somewhere below. Then he heard footsteps on the stairs. Small uneven footsteps.

The gate of someone whose legs didn’t work properly. Samuel’s hand moved instinctively to the scalpel he kept in his medical bag. A pitiful weapon, but better than nothing. A figure emerged from the darkness at the top of the stairs, small and hunched, moving down one step at a time with obvious difficulty.

As it entered the dim lamplight, Samuel recognized Oadia, the 12-year-old boy with the severely bowed legs. The child was wearing a night shirt that hung to his knees, and his face was wet with tears that reflected the lamplight like scattered diamonds. Doctor,” the boy whispered, his voice surprisingly clear, despite the physical deformities Samuel had observed earlier.

“Are you awake, doctor?” Samuel glanced at Jacob, who nodded slightly. The rifle remained ready, but the boy appeared to pose no immediate threat. Samuel shifted his position so he could see Oadiah more clearly. “I’m awake,” Samuel replied softly. “Are you in pain? Do you need medical attention? Even now, even after everything he’d learned, his physician’s instincts were automatic.

The boy was suffering. That much was obvious from his labored breathing and the way he held his misshapen body. Oadia shook his head, though the movement made him wse. “It always hurts,” he said matterofactly, as if discussing the weather. “Papa says pain is how God reminds us we’re alive, how he tests our devotion.

But that’s not why I came down. I came to warn you. The boy glanced nervously back up the stairs as if afraid someone might be listening. You have to leave at first light. Don’t let papa show you the cellar. Don’t let him take you down there. Bad things happen in the cellar. Samuel felt his mouth go dry. What kind of bad things? He needed to know, needed to understand what had happened to Thomas, even if the knowledge destroyed him.

Obadiah crept closer, his crablike shuffle making almost no sound on the wooden floor. When he spoke again, his voice was barely audible. The cellar is where Papa keeps the offerings. That’s what he calls them. Offerings to God, sacrifices to maintain the purity. When someone dies, we don’t bury them like normal folks.

Papa says their bodies still have purpose, that God wastes nothing. He takes them down to the cellar and and uses them. The boy’s voice cracked, fresh tears spilling down his cheeks. My mama died when I was eight. She bled out giving birth to my little sister who died, too. Papa took them both down to the cellar. Sometimes at night, I hear him down there and I hear, “Mama, she makes sounds, doctor.

Dead people shouldn’t make sounds.” Samuel’s medical training wared with the impossible horror of what the boy was describing. Dead bodies didn’t make sounds. That was basic biological fact. Unless Ezekiel was keeping people alive down there, keeping them in some state between life and death. No, that was impossible.

That was the stuff of Gothic novels, not reality. But [clears throat] then again, 3 days ago, Samuel would have said a family like the Harlos was impossible, too. Your brother is down there, Obadiah continued, his eyes pleading with Samuel to understand. Papa kept him for weeks before before he stopped walking around.

He was supposed to help make babies with charity and the others supposed to bring new blood into the family. But papa gave him the tea, the special tea he makes from the mushrooms that grow on the north side of the property. The tea makes you see things that aren’t there. Makes you believe things that aren’t true.

Your brother drank the tea every day and after a while he started saying the same things Papa says. started talking about purity and corruption and God’s plan. He stopped trying to leave. The picture forming in Samuel’s mind was beyond horrifying. Ezekiel had drugged Thomas, kept him prisoner while using him as breeding stock, manipulated himpsychologically until he believed he was participating willingly.

And then, when Thomas had served his purpose or tried to resist, Ezekiel had killed him and taken his body to the cellar for what? What purpose could a corpse serve? What does your father do with the bodies? Samuel asked, though part of him didn’t want to know, wanted to preserve some shred of ignorance. But Oadiah was risking punishment by coming down here by warning them.

The boy deserved to have his truth heard. Obadiah’s face contorted with misery. He says he’s preserving the essence, keeping the blood pure even after death. He cuts them open and takes out parts, organs and bones, and other things. He keeps them in jars filled with liquid, labels them with names and dates. He says every part of a pure bloodline must be preserved.

That someday when the world ends and the judgment comes, God will reassemble his chosen people from the pieces we’ve saved. But that’s not the worst part. The boy’s voice dropped to barely a whisper. Sometimes the pieces move. I’ve seen it, doctor. I’ve seen fingers twitch in their jars. I’ve seen eyes that follow you across the room, even though they’re floating in liquid and disconnected from any body.

Samuel felt bile rising in his throat. What Oadiah was describing was medically impossible, biologically absurd. Preserved organs didn’t move, didn’t retain life. But the boy believed what he was saying. Believed it with the conviction of someone who had witnessed it firsthand. Either Ezekiel had found some way to create the illusion of life in dead tissue, perhaps through electrical stimulation or chemical reactions, or Obadiah’s mind had cracked under the strain of his nightmarish existence, and he was hallucinating.

Neither explanation was comforting. “Why are you telling me this?” Samuel asked. “Why risk your father’s anger?” Oadia looked down at his malformed hands, flexing the fingers that barely worked. Because I’m dying,” the boy said simply. “I can feel it. My lungs don’t work right anymore.

I can’t breathe deeply and sometimes I cough up blood. My heart beats wrong, skips and stutters. Papa knows it, too.” He looks at me sometimes with this expression like he’s measuring me, deciding when to take me down to the cellar. I don’t want to end up in a jar, doctor. I don’t want my eyes floating in liquid, watching my family forever, but never being able to close.

never being able to rest. I want to die properly. Want to be buried in the ground where things are supposed to go when they’re finished. [clears throat] His voice broke entirely then, dissolving into quiet sobs. Samuel moved before he could stop himself, closing the distance between them and kneeling beside the boy.

Every medical instinct, every human instinct demanded that he comfort this suffering child. He placed a gentle hand on Obadiah’s shoulder, feeling the bones prominent beneath the thin night shirt. “I’m going to help you,” Samuel whispered, though he had no idea how he could possibly fulfill that promise.

“I’m going to find a way to get you out of here, to get all the children out. What your father is doing, it’s not God’s will. It’s sickness. It’s madness. God doesn’t demand suffering like this. You can’t save us all, Obadiah said with heartbreaking certainty. Most of them don’t want to be saved. They believe what Papa teaches.

They think the suffering is holy. But maybe you could take the little ones, the ones who haven’t been fully taught yet. My brother Abel is only six. He still cries for a mother who isn’t twisted. My sister Mercy is eight. She still asks why she can’t go see the world outside. If you could get them out before Papa completes their education, before they drink too much of the tea, and start believing,” he trailed off, the hope in his voice fading as reality reasserted itself.

Before Samuel could respond, before he could make promises he almost certainly couldn’t keep, they heard movement from upstairs. Heavy footsteps deliberate and measured. Ezekiel was awake. Obediah’s eyes went wide with terror, and he scrambled backward toward the stairs with his awkward crablike motion. “Don’t tell him I talked to you,” the boy pleaded.

“Please, doctor, if he knows I warned you, he’ll take me down tonight. I’m not ready. I’m not ready.” He disappeared up the stairs just as a lamp flared to life on the second floor. Ezekiel descended the stairs moments later, fully dressed despite the late hour, his amber eyes scanning the hallway until they fixed on Samuel and Jacob.

Gentlemen, he said pleasantly, as if it were perfectly normal to find them armed and awake at 2:00 in the morning. I apologize if the children disturbed you. They have nightmares sometimes. The pain makes sleep difficult. I heard Obadiah come down. I hope he wasn’t bothering you with his stories. The boy has an active imagination.

I’m afraid the inbreeding affects the mind as much as the body. He sees things that aren’t there, believesthings that aren’t true. The casual way Ezekiel acknowledged the cognitive damage he had inflicted on his own son made Samuel’s anger flare white hot. “He’s dying,” Samuel said flatly. “His respiratory system is compromised, likely from severe skeletal deformities putting pressure on his lungs.

He needs medical intervention that I cannot provide here. He needs a hospital, proper care. He needs nothing this world can offer, Ezekiel interrupted, his voice still calm, but with an edge now like silk over steel. His suffering serves God’s purpose. When his body fails, his essence will be preserved, and he will take his place with the others who have gone before.

This is our way, doctor. This has been our way for three generations. I did not bring you here to reform us or to judge us. I brought you here because God sent you just as he sent your brother. You will serve your purpose one way or another. Jacob stood slowly, his rifle coming up to rest casually in his arms.

Not quite aimed at Ezekiel, but not quite not aimed either. “We’re leaving at first light,” he said, his voice hard. “And the doctor’s right. Some of these children need help that goes beyond your twisted religion. If you try to stop us from leaving, there will be consequences. Ezekiel’s smile returned. That perfect disturbing smile.

Leave if you wish, Mr. Stern. I won’t stop you. The mountain will do that work for me. The temperature outside is currently 15° below zero. Your horses are already weakening from the cold. By morning, they may not be strong enough to carry you down the mountain, even if the trail is visible. And it won’t be.

I checked the sky before I came down. Another storm is coming. A bad one. You’ll be snowed in here for days, perhaps weeks, which means you’ll have plenty of time to understand what we do here, to see the divine logic of our mission. He moved past them toward the kitchen, pausing at the doorway. I’m making tea. Would either of you care for some? It helps with the cold.

Helps with the acceptance of difficult truths. The mushroom tea. the same drug Ezekiel had used on Thomas to break his will and make him compliant. Samuel and Jacob exchanged glances and both shook their heads. Ezekiel shrugged. “Suit yourselves. But you should know, doctor, that refusing our hospitality is considered deeply offensive in this house. We have rules here, traditions.

Break them and there are consequences. Not from me. You understand? I’m a civilized man.” But the family, well, they take these things very seriously. Some of them aren’t as mentally stable as I am. Some of them can become quite violent when they feel disrespected. It was a threat wrapped in civilized language, and Samuel heard it clearly.

Cooperate or face the violence of the family members whose damaged minds made them unpredictable and dangerous. He thought of the twisted bodies in the common room, the vacant eyes and malformed faces, and wondered which of them Ezekiel would unleash if pushed. The two young men with the severe cleft pallets had stood near the fireplace during dinner, and Samuel had noticed how they watched him with unsettling intensity, how their hands flexed and clenched as if imagining violence.

They would follow Ezekiel’s orders without question, would do whatever their patriarch commanded. Ezekiel disappeared into the kitchen, and they heard the clatter of pots and the whistle of a kettle heating. Samuel moved closer to Jacob, speaking in the barest whisper. We need to get those children out. The youngest ones, the ones who aren’t completely indoctrinated yet.

We can’t leave them here to die in jars. Jacob looked at him like he’d lost his mind. Samuel, we can barely save ourselves. How the hell are we supposed to rescue children from a family of inbredad fanatics who will kill us if we try? The frontiersman’s logic was sound, but Samuel couldn’t accept it. He had failed.

Thomas had arrived too late, had been unable to save his brother from this nightmare. But the children were still alive, still suffering. Obediah’s desperate plea echoed in his mind. If he did nothing, those children would die slowly and horribly, would end up as specimens in Ezekiel’s collection of preserved purity. I don’t know yet, Samuel admitted.

But I have to try. I took an oath as a physician. First, do no harm. Leaving those children here would be the greatest harm I could possibly commit. Jacob started to argue, then stopped, his weathered face softening slightly. Your brother would have said the same thing,” Jacob said quietly. “Thomas was always trying to help people, even when it put him in danger.

” “Yes, it runs in the family,” he adjusted his grip on the rifle. “All right, we’ll figure something out. But Samuel, if it comes down to a choice between saving them and saving ourselves, we save ourselves.” “Deal?” Samuel nodded, though he wasn’t certain he meant it. They spent the rest of the night in tense silence, waiting for dawn that seemed determined never toarrive.

At some point, Samuel heard footsteps upstairs again, multiple sets this time, light and uneven. The children were awake, beginning their day. He heard Ezekiel’s voice raised in what sounded like a prayer or sermon. The words indistinct, but the cadence familiar, the rhythm of religious instruction, of dogma being hammered into young minds already compromised by physical suffering and isolation.

Samuel thought of Oadia’s warning of the mushroom tea that twisted perception and belief, and wondered how many of those children upstairs had already been drugged into accepting their nightmare as divine will. Finally, mercifully, gray light began seeping through the cracks around the shuttered windows. Dawn had arrived, though the quality of light suggested heavy cloud cover.

Samuel and Jacob moved to the window and carefully opened one shutter. What they saw made Samuel’s heart sink. Snow was falling again, not the light flurries of the previous day, but a genuine blizzard with winddriven snow so thick they could barely see the corral 20 ft away. The horses were huddled together, covered in snow, their heads down against the wind.

Ezekiel had been right. They were trapped here possibly for days. “God help us,” Jacob muttered, closing the shutter. We’re at his mercy now. Samuel didn’t respond. He was thinking about the cellar, about what Obadiah had described, about Thomas’s body lying somewhere in that darkness among jars of preserved tissue and organs that supposedly moved on their own.

He was thinking about Charity’s swollen belly, about the baby that would soon be born into this house of horrors, another generation of genetic catastrophe. and he was thinking about the choice Ezekiel had offered him. Help willingly, or join Thomas in the cellar. Samuel had always considered himself a rational man, a man of science and reason.

But standing in that dark hallway, while a blizzard raged outside, and madness reigned within, he felt his certainty crumbling. What if Oadiah was right? What if there was something unnatural in that cellar? Something that defied medical explanation? What if three generations of inbreeding in isolation had created not just physical deformities, but something else, some alteration in the family’s very nature.

He pushed those thoughts away. Monsters weren’t real. The only monster here was Ezekiel Harlow, a man who had taken his grandfather’s twisted theology and built a three generation nightmare from it. The horror was entirely human, entirely explicable, and that somehow made it worse because humans could be reasoned with, could be stopped, could be brought to justice.

But first, Samuel had to survive long enough to make that happen. The children began filing down the stairs, summoned by Ezekiel’s voice. They moved in a line, oldest to youngest, each taking their place at the breakfast table. and Samuel saw in their faces the full spectrum of what this family had become. From the 16-year-old constants whose eyes tracked independently and whose fused fingers clutched at her dress to the three-year-old who could barely hold his head up and made only animal sounds.

22 people bound by blood so close it had become poison, so pure it had become corruption. This was Ezekiel’s achievement, his twisted legacy. And if Samuel didn’t find a way to stop it, this horror would continue until the family line finally collapsed entirely. Until the last Harlow died in agony, believing their suffering was holy.

Breakfast was served. Samuel forced himself to eat, knowing he needed strength for whatever was coming. And through it all, Ezekiel watched him with those amber eyes, that perfect smile, waiting to see what choice the good doctor would make, waiting to see if Samuel would become willing sacrifice like Thomas, or if he would require more direct persuasion.

The snow continued to fall outside, sealing them in, and somewhere below their feet. In the darkness of the cellar, the offerings waited in their jars, preserved in liquid, their essence kept pure for a resurrection that would never come. After breakfast, Ezekiel invited Samuel into what he called his study, a small room off the main hall, lined with shelves containing books, journals, and an array of glass jars that Samuel deliberately avoided looking at too closely.

The morning light filtering through the single window was gray and weak, barely illuminating the space. A fire crackled in a small hearth, providing minimal warmth against the cold that seemed to seep through the very walls. Jacob remained in the main room with the family, his rifle never far from his hands, his eyes tracking every movement.

Samuel had insisted on this arrangement. Neither of them would be alone with the Harlows. not after Obadiah’s warning, not after everything they had witnessed. Ezekiel settled into a worn leather chair and gestured for Samuel to take the seat opposite. Between them sat a small table covered with papers, drawings, and what appearedto be genealogical charts traced in meticulous detail.

Samuel recognized the format, family trees, though these were unlike any he had seen before, where normal genealogies branched outward with each generation. The Harlow tree folded back on itself repeatedly, the same names appearing in multiple positions as siblings, married siblings, and parents produced children with their own offspring.

It was a genetic spiral, not a tree. each loop tightening until the pattern became almost impossible to follow. “You think me a monster,” Ezekiel said conversationally as if discussing the weather. “I can see it in your face, doctor. You look at my family and see suffering, deformity, tragedy. But that’s because you view the world through the corrupted lens of modern medicine and secular philosophy.

Let me show you what I see. Let me help you understand the divine mathematics of purity.” He pulled one of the genealogical charts closer and began tracing the lines with his finger. My grandfather Josiah Harlow was a mathematician and theologian. He understood something that the modern world has forgotten that God works through numbers, through sacred geometry, through the pure mathematics of bloodlines.

Samuel wanted to interrupt, wanted to explain basic genetics and the catastrophic consequences of inbreeding, but he held his tongue. Ezekiel was going to explain his twisted logic regardless. And Samuel needed to understand the depth of the madness he was dealing with. Know your enemy, his medical school professors had taught him.

Understand the disease before you attempt to cure it. Josiah studied the ancient texts. Ezekiel continued, his voice taking on the cadence of a lecturer. Not just the Bible, but older texts, the Apocrypha, the Gnostic Gospels, the hermetic traditions. He discovered that the great patriarchs of the Old Testament practiced what we would now call inbreeding.

Abraham married his halfsister Sarah. Isaac and Rebecca were cousins. Jacob married two sisters and fathered children with both plus their handmmaids. These were not accidents or cultural necessities. They were deliberate choices to maintain bloodline purity. God commanded it through implication, through example. Ezekiel’s amber eyes gleamed with fervent conviction.

But the church, corrupted by Roman philosophy and Greek rationalism, moved away from this truth. They began advocating for marriage outside the bloodline, mixing the pure with the impure. And look at the result. Disease, weakness, moral corruption spreading through humanity like a plague. The logic was so fundamentally flawed, so divorced from biological reality that Samuel didn’t know where to begin refuting it.

The Old Testament marriages Ezekiel cited were products of their time and culture, not divine mandates for genetic purity. And the physical evidence of what inbreeding produced sat in the room beyond them. Children struggling to breathe, to walk, to think clearly. But Ezekiel had constructed an entire theological framework to justify and sanctify their suffering.

My grandfather brought his wife Rebecca and their three children, two daughters and a son to this mountain in 1767. Ezekiel continued, “He built this house with his own hands, cleared the land, established the homestead, and then he began the great work. When his eldest daughter, Rebecca, turned 16, he took her as his second wife.

Rebecca, his first wife, accepted this as God’s will. Josiah fathered five children with Rebecca. my father Nathaniel among them. When Rebecca’s sister Ruth came of age, Josiah took her as well. Seven more children. The bloodline was being purified, concentrated, strengthened through sacred repetition. Samuel’s medical training screamed at every word.

What Ezekiel described wasn’t purification. It was genetic catastrophe in slow motion. Each generation of inbreeding increased the likelihood that recessive genetic disorders would manifest, that accumulated mutations would express themselves, that the biological mechanisms meant to ensure genetic diversity would fail catastrophically.

The human genome required variation to remain viable. Closin breeding was nature’s forbidden territory for excellent evolutionary reasons. The first generation showed minimal effects. Ezekiel admitted a few minor abnormalities. A hair lip here, a club foot there. My grandfather interpreted these as birth pangs, the necessary suffering that accompanies any great transformation.

He kept meticulous records documenting every birth, every trait, every variation. Ezekiel opened one of the journals on the table, revealing page after page of cramped handwriting interspersed with detailed anatomical drawings. Samuel glimpsed sketches of malformed skulls, twisted limbs, organs in wrong positions. It was a catalog of genetic horror presented as scientific observation.

When my father Nathaniel came of age, he married his sister Ruth, the same name as his mother’s sister. You see, we maintainnaming traditions as well as bloodline purity. They produced eight children, though only five survived past infancy. I was the eldest. My siblings were Ezra, Miriam, Constance, and Abel. The physical manifestations were more pronounced in our generation, more significant skeletal deformities, some cognitive impairment in my younger siblings.

But grandfather Josiah saw this as progress. The dross was being burned away, he said. The bloodline was being refined like silver in a crucible. Samuel couldn’t remain silent any longer. Mr. Harlo Ezekiel, what you’re describing isn’t refinement. It’s genetic collapse. The human body requires genetic diversity to function properly.

When close relatives reproduce, they’re more likely to share the same recessive genes, including those carrying harmful mutations. Each generation of inbreeding increases the risk exponentially. The conditions I’ve observed in your family, the skeletal deformities, the cognitive impairments, the organ dysfunction, these are not divine refinement.

They’re the predictable consequences of repeated consanguinous reproduction. Ezekiel’s smile never wavered. I know the arguments of modern medicine, doctor. I’m not an ignorant man. My grandfather’s library contained medical texts as well as theological ones. He understood what men of science would say about our practices.

But science can only measure the physical world. It cannot measure the spiritual dimension. Cannot quantify the soul’s purity. Yes, our bodies suffer. Yes, we bear physical burdens that would horrify the outside world. But our souls, doctor, our souls are being perfected. Every deformity is a prayer made flesh.

Every shortened life is a martyrdom that brings us closer to God’s throne. The complete inversion of reality. The absolute conviction with which Ezekiel spoke his madness was almost mesmerizing in its horror. Samuel had encountered delusional patients before had treated people whose minds had fractured under the weight of grief or trauma.

But this was different. This was systematic, multigenerational delusion, carefully constructed and passed down like an inheritance. Ezekiel had been born into this nightmare, raised to believe suffering was holy, taught from infancy that the agonies of his family were sacred duties. How did you reason with someone whose entire reality was built on such a fundamentally corrupted foundation? When I came of age, Ezekiel continued, turning pages in the journal.

I married my sisters Miriam and Constance. Both bore children, 14 in total, though only nine survived. You’ve met some of them. Charity, the one carrying my child now, is from my union with Miriam. Oh, Badiah, the boy with the respiratory issues, is from Constance. My brother Ezra married our sister Constance as well.

Yes, she had two husbands, both her brothers. This is not sinful, doctor. This is holy multiplication. The sacred mathematics my grandfather discovered. Every child represents another iteration of purity. Another step toward the perfect bloodline God intended before the fall corrupted humanity. Samuel felt sick. The casual way Ezekiel discussed raping his own sisters, impregnating his own daughters, creating children whose bodies were so compromised they could barely function.

It was beyond monstrous. Yet Ezekiel showed no shame, no recognition that what he described was among the worst crimes human beings could commit. He spoke of it with the pride of a craftsman discussing his finest work. But then we encountered a problem, Ezekiel said, and for the first time Samuel heard something other than serene confidence in his voice.

The third generation, my children, their fertility is compromised. Many of the females cannot carry pregnancies to term. Those who can often die in childbirth as their pelvises are too malformed to allow normal delivery. The males have difficulty performing their duties. Low sperm counts, physical abnormalities that prevent proper congress.

My grandfather’s journals predicted this. He called it the valley of testing, the point where faith would be most challenged. The bloodline was becoming so pure, so concentrated that it was approaching a kind of critical mass. We needed to either push through to the next level or accept failure. Samuel seized on this admission.

Then you understand that your practices are unsustainable. The family cannot continue this way. The genetic damage is too severe. If you truly want your bloodline to survive, you need to introduce new genetic material. Need to marry outside. No. Ezekiel’s voice cracked like a whip. The first real emotion breaking through his calm facade. That would undo everything.

Three generations of sacrifice, of devotion, of suffering, all wasted if we corrupt the blood. Now we were so close, doctor. So close to achieving the final purity. But we needed assistance. Fresh genetic material. Yes. But introduced correctly, sacredly. Not through random mixing with corrupted outside stock. Heleaned forward, his amber eyes intense.

That’s where your brother came in. Thomas was perfect, young, healthy, intelligent. When he arrived here, I knew God had sent him. I explained our situation, showed him the journals, helped him understand the divine mission. And after he drank the sacred tea for a few days, after his mind opened to the truth, he agreed to help us.

He mated with three of my daughters, charity, faith, and constants. He gave them his seed willingly, blessing them with fresh blood that could strengthen the line without corrupting it. The image of Thomas drugged and coerced into this nightmare made Samuel’s hands clench into fists. “You murdered him,” he said flatly. “You kept him prisoner. You drugged him until his mind broke.

You forced him to participate in your madness, and then you killed him. That’s not divine mission. That’s kidnapping, rape, and murder. Ezekiel shook his head slowly. Your brother understood what we couldn’t. That sometimes the physical body must be sacrificed so the spirit can achieve its highest purpose.

He gave himself completely to our cause. And when his body began to fail, the tea is hard on the organs, I admit, especially when consumed in the quantities necessary for complete enlightenment. He went to his rest, knowing he had served God’s plan. His body now rests in the cellar, but his essence continues to serve us.

The children he fathered are being carried even now. In a few months, we’ll see the fruits of his sacrifice. Babies with fresh blood but pure purpose. the next step in our divine evolution. Samuel stood abruptly, unable to bear sitting any longer. I want to see the cellar. I want to see where my brother is.

The words came out before he could stop them, driven by a need to confirm the horror, to see with his own eyes what Oadiah had described. Ezekiel regarded him silently for a long moment, then smiled that perfect, terrible smile. Of course, doctor, I always intended to show you. The cellar is the heart of our sacred work, the place where flesh and spirit intersect, where the offerings are prepared and preserved for the great resurrection.

But I must warn you, what you see there will challenge everything you believe about the boundaries between life and death, between the possible and impossible. My grandfather discovered something in his studies. Something the ancient texts hinted at but never fully explained. A way to preserve not just the body but the life force itself.

Suspended in the moment between death and dissolution. The modern world has forgotten these techniques, dismissed them as superstition. But they work, doctor. They work in ways that will horrify your rational mind. Ezekiel stood and moved toward the door. The seller awaits and so does your brother. What remains of him at least.

Samuel followed, his heart hammering against his ribs. Jacob noticed them moving and immediately fell in step, rifle ready, his weathered face grim. They descended through the main room where the Harlow family was engaged in various morning activities. the women cooking and cleaning, the older children helping with chores, the severely impaired ones simply sitting and staring at nothing.

They all stopped what they were doing to watch Samuel and Jacob follow Ezekiel toward a heavy door at the rear of the house. The collective gaze of those amber eyes, all tracking them with unsettling synchronization, made Samuel’s skin crawl. Ezekiel produced a large iron key and unlocked the door, which opened with a groan of old hinges onto darkness.

Stone steps descended into blackness, and the smell that wafted up made Samuel’s gorge rise. That same sweet rot he had detected upon arrival. But concentrated now, mixed with chemical odor he couldn’t identify, and something else, something organic and wrong, Ezekiel lit a lantern and began descending the stairs.

Stay close,” he said pleasantly. “The cellar is extensive. My grandfather and father expanded it over the decades. There are many rooms, many chambers. You wouldn’t want to get lost down here. People who lose their way in the dark sometimes never find their way back to the light.” Samuel exchanged one last look with Jacob, seeing his own terror reflected in the frontiersman’s eyes.

Then they followed Ezekiel down into the darkness, down into the cellar where Thomas waited. down into the heart of the Harlow family’s madness. The stone steps were slick with moisture, the walls pressing close on either side. The temperature dropped with each step, far colder than the house above, cold enough that Samuel could see his breath despite the lantern’s warmth.

And from somewhere deep in the darkness ahead, he heard sounds, soft sounds, wet sounds, sounds that might have been water dripping, or might have been something else entirely. something that shouldn’t exist but did preserved in jars and liquid waiting in the dark where the offerings rested. The lantern light caught on something asthey reached the bottom of the stairs.

Rows of glass jars lining shelves carved into the stone walls, each containing shapes that might have been organs or might have been something else. Floating in clear liquid that occasionally caught the light and reflected it back like eyes. So many jars, dozens of them, perhaps hundreds.

Samuel’s rational mind insisted they were medical specimens preserved tissue for study. But some of the shapes were too large to be individual organs, too complex to be simple anatomical samples. And as the lantern light moved across them, Samuel could have sworn he saw movement inside several jars, subtle shifts, as if the contents were responding to the light or to the presence of living people nearby.

Welcome to the heart of purity, Ezekiel said, spreading his arms to encompass the cellar. Welcome to where the sacred work is done. Your brother is here, doctor. several parts of him at least preserved and pure, waiting for the resurrection. Would you like to see which jars contain him? Would you like to understand what he’s become? The lantern cast dancing shadows across Ezekiel’s face, making his features shift and change, making him look less human and more like something else.

Something that wore a human shape, but had left humanity behind long ago in pursuit of an impossible purity. Samuel couldn’t speak, couldn’t move. He simply stared at the jars, at the shapes floating in their liquid prisons, and felt his sanity beginning to crack under the weight of what he was seeing. Jacob’s hand gripped his shoulder, anchoring him, keeping him from falling into the abyss of horror that yawned before them.

And somewhere in the darkness beyond the lantern’s reach, something made a sound, wet and soft and wrong. The sound of flesh moving when flesh should be still. The sound of preservation failing or succeeding in ways that violated every natural law. Ezekiel’s smile widened. Let me show you the greatest achievement of our sacred work.

Let me show you what three generations of purity and suffering have created. Come, doctor. Come and see what your brother has become in service to God’s plan. He moved deeper into the cellar. the lantern light receding, darkness closing in behind him like a living thing. And Samuel, God help him, followed. Because he had to know, because Thomas was his brother, because some truths, no matter how terrible, demanded to be witnessed.

The seller waited, the offerings waited, and in the jars things that should not move continued their subtle, impossible movements preserved forever in the moment between life and death, between purity and corruption, between the human and something else entirely. The cellar extended far beyond what the house’s footprint should have allowed, sprawling into chambers carved directly from the mountain stone.

Ezekiel led them through a warren of interconnected rooms. Each one lined with more shelves, more jars, more shapes floating in amber liquid that caught and held the lantern light. Samuel’s medical training kept trying to categorize what he was seeing. Hearts, livers, sections of brain tissue, lengths of intestine, but the classifications felt inadequate, incomplete.

Some of the specimens were too large, their shapes too complex to be simple organs, and the movement he had noticed earlier was undeniable now, not constant, not dramatic, but present. A finger would flex inside its jar, and I would rotate slowly, as if tracking their passage through the room. A heart would contract once, twice, then fall still again.

Jacob had gone pale, his rifle gripped so tightly his knuckles had turned white. “This ain’t natural,” he whispered. his voice tight with barely controlled panic. This ain’t possible. Dead things don’t move. They can’t. But they were moving, and no amount of denial could change that observable fact. Samuel’s rational mind scrambled for explanations.

Perhaps electrical stimulation from some hidden mechanism. Perhaps chemical reactions in the preservative fluid creating the illusion of life. Perhaps even deliberate fraud with hidden wires and pulleys. But none of those explanations felt adequate when faced with the reality before them. And I was watching him right now, its pupil contracting as the lantern light passed near it, a response that required functioning neural tissue and impossible preservation of biological processes.

Ezekiel stopped in a larger chamber where a wooden table dominated the center of the space. The table’s surface was stained dark with substances Samuel didn’t want to identify, and arrayed around it were surgical instruments, scalpels, saws, clamps, tools that looked both medical and medieval. Against one wall stood what appeared to be a massive ledger book, its pages thick with entries written in the same cramped handwriting Samuel had seen in the journals upstairs.

My grandfather began the preservation work in 1770, Ezekiel explained, running his hand almost lovingly over the surgical table.He understood that if the bloodline was to achieve final purity, nothing could be wasted. Every death in service of the divine plan had meaning, had purpose. The body might fail, but the essence, the concentrated genetic material, the purified blood, the organs shaped by generations of sacred breeding, these had to be preserved.

Samuel forced himself to speak. To engage with the madness in hopes of understanding it. Preservation of tissue requires specific chemical processes. Formaldahhide, alcohol, other fixatives. Even then, cellular function ceases. The tissue becomes inert, dead in every meaningful sense. What you’re showing me, what I’m seeing in these jars, it’s impossible.

The metabolic processes necessary for movement require oxygen, glucose, functioning cell membranes. None of that can exist in preserved tissue. He was reciting medical facts like a prayer, like incantations that might ward off the horror surrounding them. Ezekiel’s amber eyes gleamed with something approaching pity.

Modern medicine is so limited, doctor. It sees only the physical mechanisms, the chemical processes, the biological machinery. It’s blind to the vital force, the life essence that animates flesh. My grandfather studied the old texts, the alchemical treatises, the hermetic writings, the secret knowledge the church suppressed.

He learned that life is not merely chemical reaction but a force that can be captured, suspended, preserved through the proper techniques. The fluid in these jars is not simple formaldahhide. It contains extracts from certain mushrooms that grow on the north side of this mountain. minerals dissolved from specific rock formations, and most importantly, blood from the living members of the family, refreshed monthly through careful donation.

The implication hit Samuel like a physical blow. The family was feeding their own blood to these preserved remains, creating some kind of grotesque symbiosis between the living and the dead. That’s why you keep them, he said slowly, understanding dawning, not just as specimens or records. You believe they’re still alive somehow, still part of the family.

You’re maintaining them with blood donations, keeping them in some state between life and death. The sheer insanity of it was staggering, but it explained the family’s palar, their weakness. They were all chronically anemic, regularly giving blood to maintain Ezekiel’s collection of impossible specimens. They are the family, Ezekiel corrected gently.

The blood connects us across generations, across the boundary of death. Every harlow who has died in service of purity lives here still, watching over us, waiting for the great resurrection when God will restore them to perfection. My grandfather Josiah is here. His brain in that jar on the third shelf.

His heart two jars to the left. My grandmother Rebecca. My father Nathaniel. My mother Ruth. My siblings who died in infancy. My own children who were too weak to survive. All of them preserved. All of them waiting. And now your brother Thomas joins them. His essence added to our sacred collection. Samuel’s stomach lurched.

Where is he? Where is Thomas? The question came out as barely more than a whisper. Ezekiel moved to a section of shelving near the back of the chamber, where newer jars sat with labels still crisp and clear. He selected one and held it up to the lantern light. Inside, floating in that strange amber liquid, was a human heart. But unlike the other organs Samuel had before inevitable death, he told himself this as he worked, trying to silence the voice in his head that screamed he was committing murder.

The baby was delivered at 3:00 in the morning, born dead or dying. Its malformed body a testament to everything wrong with the Harlow bloodline. Samuel wrapped it quickly in a cloth, not letting anyone else see the full extent of the deformities. Charity had mercifully lost consciousness during the final stages of delivery, her body’s way of protecting her from trauma too severe to process.

Samuel focused on stopping her hemorrhaging, packing the uterus with cloth, administering what medicines he had that might help. Her pulse was thready and weak, her breathing shallow. She might survive the night, but infection was almost certain in these conditions, and her compromised immune system would struggle to fight it off.

Ezekiel stepped forward and took the wrapped bundle from Samuel’s arms. He carried it to the window, unwrapping the cloth to examine what remained of his grandchild. Samuel watched his face, expecting anger or grief or accusation. Instead, he saw only that same serene acceptance, as if the baby’s horrific deformities and death confirmed rather than contradicted his worldview.

The burden of purity, Ezekiel said softly. This child bore too much. The weight of divine purpose crushed its physical form. But the essence is preserved. The blood, the tissue, the genetic material, all will go to the cellar will join thefamily in waiting. Nothing is wasted in God’s plan.

The casual way he discussed adding his dead grandchild to his collection of preserved horrors made Samuel’s exhaustion dulled anger flare bright and hot. “That child died because of you,” he said, his voice low and dangerous. “Because of three generations of deliberate genetic destruction. Because your grandfather was insane and convinced your family that suffering was holy.

Every deformed child, every early death, every scream of pain, they’re all consequences of choices your family made. Not God’s will, not divine purpose, just human evil dressed up in religious language. For the first time, something flickered across Ezekiel’s face. Genuine anger barely controlled. “You understand nothing,” he hissed. “You see only the physical suffering, only the broken bodies.

You’re blind to the spiritual achievement, to the purity we’ve maintained while the entire world fell into corruption. My grandfather understood what fools like you can never grasp. That some goals require sacrifice. That perfection demands a price. We’ve paid that price gladly, generation after generation, keeping our blood pure while yours grows weaker and more polluted.

This child’s death is not tragedy, but martyrdom, not failure, but transcendence. He moved toward the door, still carrying the wrapped bundle. I’m taking this to the cellar for proper preparation. Stay with charity. Keep her alive if you can. She still has value. Can potentially bear other children if she recovers. But know this, doctor.

You’ve served our purpose now. You’ve helped deliver the baby, proven your skills. Tomorrow, we’ll discuss your permanent role in the family. You’ll drink the tea willingly or you’ll drink it by force. Either way, you’ll come to understand what your brother understood. There is no escape from this mountain, from this house, from God’s plan.

He left, descending the stairs with his terrible burden. Samuel heard the cellar door open and close, then silence, broken only by charity’s labored breathing and the wind howling outside. Jacob stood in the corner, his face ashen, his hands shaking. We have to get out of here, the frontiersman whispered. Tonight, storm or no storm.

If we stay, he’ll drug us, turn us into into whatever he made Thomas into. I’d rather freeze to death on the mountain than end up in a jar down there. Samuel wanted to agree, wanted to grab their coats and run into the frozen darkness. But Charity lay dying in the bed before him, and there were children in this house who still had a chance at life beyond this nightmare.

We’re not leaving alone, Samuel said quietly. We’re taking the youngest children with us. The ones Oadiah told me about, Abel and Mercy, and any others young enough that the indoctrination hasn’t completely taken hold. We’re getting them out, even if it kills us trying. Jacob stared at him like he’d lost his mind. Samuel, we can barely save ourselves.

How are we supposed to evacuate children through a blizzard while being pursued by a family of inbredad fanatics? The question was valid, the objection reasonable. But Samuel thought of Thomas, of how his brother had tried to help these people and been destroyed for it. He thought of the jars in the cellar, of hearts beating in impossible preservation, of all the lives wasted in service of Josiah Harlow’s mad vision.

Someone had to stop this cycle. Had to prevent another generation from being born into suffering. I don’t know, Samuel admitted. But I have to try. I’m a physician. My oath is to heal to prevent suffering. If I walk away from those children, I’m no better than Ezekiel, justifying evil for the sake of principle.

He checked Charity’s pulse again, still weak, but stable for now. She would live or die based on factors beyond his control at this point. Infection, hemorrhage, shock, any could claim her in the next 24 hours. But his immediate responsibility was fulfilled. He had done [clears throat] what he could with the tools and knowledge available.