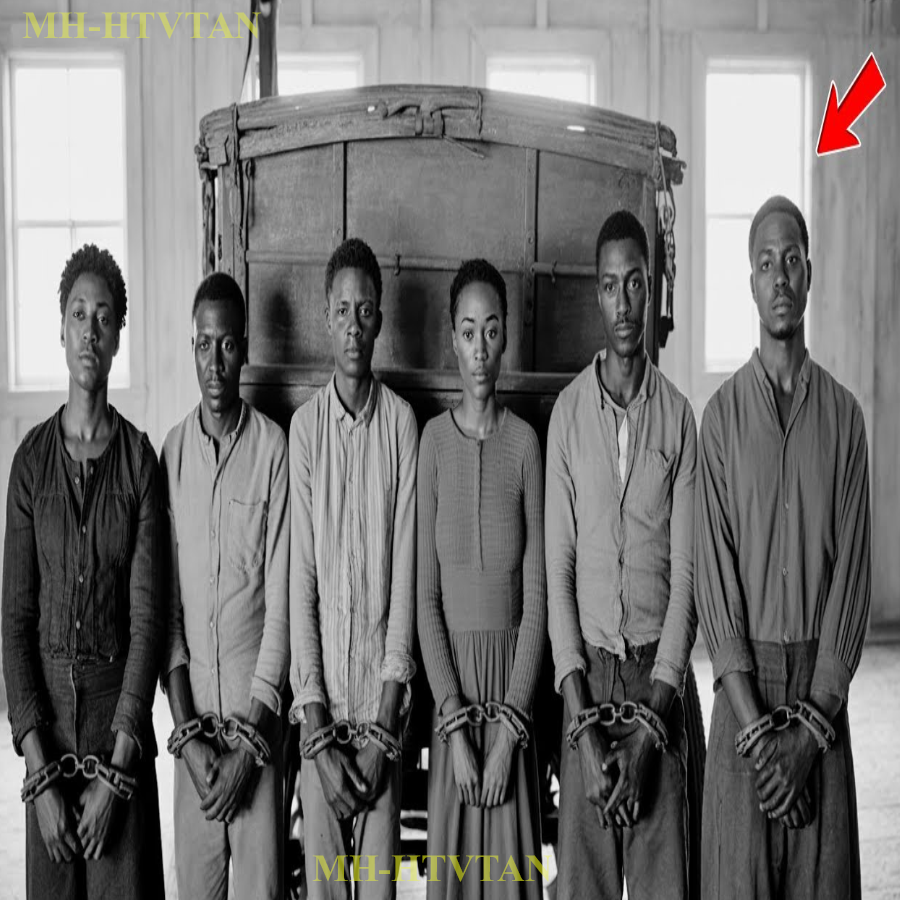

Today’s story takes us to 1859 and follows Saraphina Drake, an enslaved black girl whose beauty became a curse. The mistress couldn’t stand the attention Saraphina drew.

And what she did next was beyond cruelty. She kept her chained and hidden for 10 long years. This is a difficult and intense story, so take a moment, breathe, and listen carefully.

In the spring of 1859, in a small cabin behind the Witmore plantation in Warren County, Mississippi, a baby girl was born with eyes the color of amber and skin that seemed to glow even in the dim candle light. Her mother, a field slave named Ruth, looked at her newborn daughter and felt something she had rarely experienced in her 32 years of bondage.

She felt fear, not the ordinary fear of the overseer’s whip or the master’s temper. This was a different kind of terror. Ruth understood with the instinct that only a mother can possess that her daughter’s extraordinary beauty would become either her salvation or her destruction. She named the child Saraphina after the highest order of angels.

It was a name she had heard the plantation mistress read aloud from a book of religious poetry years earlier. Ruth could not read or write, but she never forgot that word. Saraphina, the burning ones, the angels closest to God. She whispered it into her daughter’s ear that first night, praying that perhaps heaven might protect what she knew she could not.

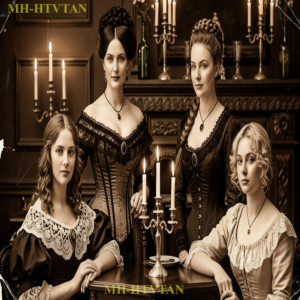

The Witmore plantation stretched across 1,800 acres of some of the richest cotton land in the Mississippi Delta. The main house sat on a gentle rise overlooking the fields, a two-story Greek revival mansion with white columns and wide veranders that seemed to mock the suffering that made its grandeur possible.

In 1859, the plantation held 147 enslaved people and it produced nearly 500 bales of cotton each year, making the Witmore family one of the wealthiest in the region. The master of the house was Colonel James Whitmore, a 63-year-old man with a reputation for running what he called a tight operation. He rarely visited the slave quarters himself, leaving the daily management to his overseers and his wife.

James Whitmore spent most of his time in Vixsburg, attending to business matters and political meetings. He served two terms in the Mississippi State Legislature and considered himself a gentleman of the highest order. He owned human beings as casually as he owned horses or furniture, never questioning the morality of the institution that had made him rich.

But the true power of the Witmore household resided not with the colonel, but with his wife, Helena. She was 41 years old in 1859, a woman who had once been considered the most beautiful debutant in Nachez society. Time and disappointment had hardened her features and poisoned her heart. She had given her husband three sons, all of whom survived to adulthood, and she considered this her greatest accomplishment.

But Helena Whitmore lived with a secret bitterness that colored everything she did. She knew her beauty was fading. She saw it in the mirror every morning, in the fine lines around her eyes and the slight loosening of her jaw, and she could not bear it. Helena ruled over the domestic slaves with an iron hand.

She personally supervised the house servants, the cooks, the laresses, and the nursemaids. Nothing escaped her attention. She prided herself on maintaining what she called proper order, which meant complete submission from every enslaved person who worked inside her home. The field slaves answered to the overseers. The house slaves answered to Helena.

and Helena answered to no one. For the first 7 years of her life, Saraphina lived in relative obscurity. She stayed with her mother in the small cabin behind the main house where Ruth worked as aress. The work was brutal. Ruth spent 14 hours a day washing, boiling, and pressing the fine linens and clothing of the Witmore family.

Her hands were permanently scarred from the lie soap and scalding water. But she kept her daughter close, teaching her to stay quiet, stay invisible, and stay alive. Saraphina learned these lessons well. She helped her mother carry water from the well, and sort the dirty laundry. She learned to fold sheets so perfectly that not a single wrinkle remained.

She learned to walk softly, speak only when spoken to, and never look a white person directly in the eye. These were the rules of survival that every enslaved child absorbed before they could even understand their meaning. But there was one thing Ruth could not teach her daughter to hide. She could not dim the light that seemed to radiate fromSaraphina’s face.

By the time the girl turned seven, her beauty had become impossible to ignore. Her amber eyes seemed to change color with the light, shifting from deep gold to honey brown. Her features were perfectly symmetrical, almost unnaturally so, with high cheekbones and a delicate chin. Her skin was flawless, a deep brown that seemed to hold warmth even in the coldest weather.

And when she smiled, which she rarely did, the effect was almost startling. The other enslaved people noticed first. They whispered among themselves, some in admiration and some in warning. “Old Bessie, who worked in the kitchen and claimed to have the gift of sight, told Ruth to keep that child hidden. That kind of pretty brings nothing but trouble,” she said.

“Either the men going to want her or the women going to hate her. Either way, it ends in blood.” Ruth tried. She kept Saraphina in their cabin as much as possible. She dressed the girl in the plainest, most shapeless clothes she could find. She rubbed dirt on her face and kept her hair wrapped tight under a rough cloth.

But beauty like Saraphinas could not be concealed any more than the sun could be hidden behind a handkerchief. It shone through everything. The day that changed everything came in September of 1859. The summer heat had finally broken and Helena Whitmore decided to walk through the domestic work areas to conduct one of her inspections.

She did this periodically, appearing without warning to criticize the work of the enslaved people and remind them of their place. On this particular afternoon, she walked past the laundry area just as Saraphina emerged from the cabin carrying a basket of folded linens. The girl did not see the mistress approaching.

She was focused on balancing the heavy basket, trying not to drop any of the carefully pressed sheets. The cloth had slipped from her head, and her hair, which Ruth had tried to keep hidden, fell in soft waves around her face. The afternoon sun caught her at just the right angle, illuminating her features with a golden light.

Helena Whitmore stopped walking. She stood perfectly still for several seconds, staring at the child with an expression that witnesses would later struggle to describe. It was not anger, not exactly. It was something deeper and more dangerous. It was the look of a woman confronting something she could not accept. Ruth saw the mistress and felt her blood turned to ice.

She dropped the shirt she was ringing and rushed toward her daughter, but she was too late. Helena had already seen. And what Helena saw, she could never unsee. That night, Helena lay awake in her canopied bed, staring at the ceiling while her husband snored beside her. She could not stop thinking about the slave girl. She could not stop comparing.

When she closed her eyes, she saw those amber irises and that perfect skin, and she felt a rage building inside her that frightened even herself. How dare this child, this piece of property, possess what Helena was losing? How dare she exist at all? By morning, Helena had made her decision. She told herself it was about discipline.

She told herself it was about maintaining proper order. She told herself the girl had been insolent, had failed to show proper respect, had looked at her with defiance. None of these things were true. But Helena repeated them until she almost believed them herself. The truth, which she would never admit, even in the privacy of her own mind, was much simpler.

She could not bear to look at Saraphina, and if she could not destroy the girl’s beauty, she would hide it where no one would ever see it again. The cellar beneath the Witmore mansion had been used for storage since the house was built in 1841. It was a large space nearly 40 ft long and 20 ft wide with stone walls and a dirt floor.

One section had been converted into a wine cellar where the colonel kept his collection of imported French wines. But the back portion of the cellar remained unused, a dark and damp space that even the house servants rarely entered. This was where Helena decided to put the girl. She gave the orders to the overseer, a man named Thomas Krenshaw, who carried them out without question.

He was paid well not to ask questions. That evening, after the colonel had retired to his study with a glass of brandy, two of the domestic slaves came to Ruth’s cabin under Caw’s supervision. They took Saraphina while Ruth screamed and begged. They dragged her across the yard and into the main house through the back entrance.

They carried her down the wooden stairs into the cellar, and they chained her to an iron ring that had been bolted into the stone wall. Ruth tried to follow. She fought against the hands that held her back, scratching and biting like a wild animal. Krenshaw struck her across the face with the back of his hand, knocking her to the ground.

“If you say one word about this,” he told her, “I will sell you to the traders, and you will never see thisplace again. You will never know what happened to your girl. You understand me? Ruth understood. She understood that she was powerless. She understood that her daughter had just been swallowed by the earth.

And she understood that there was nothing she could do about it. The first night in the cellar, Saraphina did not understand what was happening. She cried for her mother until her voice gave out. She pulled at the chain around her ankle until the iron cut into her skin and blood ran down her foot.

She called out for help, but her voice could not penetrate the thick stone walls and the heavy wooden door at the top of the stairs. No one came. No one would come. The cellar was almost completely dark. A tiny window, no bigger than a man’s hand, sat high on the wall near the ceiling. It let in a thin sliver of daylight during the afternoon hours, just enough to distinguish day from night.

But for most of the time, Saraphina existed in total blackness. She could not see her own hands in front of her face. She could not see the walls that imprisoned her. She could only feel the cold stone beneath her body and the weight of the chain on her leg. Helena established a routine that would continue for the next 10 years. Twice a day, a kitchen slave would bring a bowl of food down to the cellar.

In the morning, it was usually cold cornmeal mush. In the evening, it was whatever scraps remained from the family’s dinner. The slave who brought the food was forbidden to speak to Saraphina. They were forbidden to bring a light. They were forbidden to tell anyone about the girl in the cellar. Helena made it clear that any violation of these rules would result in immediate sale to the slave traders who regularly passed through Vixsburg.

For the first few months, Saraphina screamed whenever someone opened the cellar door. She begged them to release her. She promised to be good, to be invisible, to do whatever they wanted. But the slaves who brought her food could not help her even if they wanted to. They were as trapped as she was, imprisoned by a system that gave them no power and no choices.

They left the food and they left. And Saraphina remained alone in the darkness. Time became meaningless in the cellar. Without the regular rhythm of day and night, without work to structure her hours, Saraphina lost track of how long she had been imprisoned. Days blended into weeks. weeks dissolved into months. She slept when she was tired.

She ate when food appeared. She cried until she had no tears left. And then slowly something inside her began to change. The human mind is remarkably adaptable. Faced with conditions that should have driven her to madness, Saraphina’s consciousness found ways to survive. She began to create structure out of nothingness.

She counted her breaths in sets of 100. She recited every word she could remember her mother saying, playing conversations over and over in her memory until they became as real as any physical object. She traced patterns on the stone floor with her fingers, memorizing their shapes in the darkness. She invented games, stories, entire worlds that existed only in her imagination.

But the most important adaptation Saraphina made was learning to listen. The cellar sat directly beneath the main floor of the Witmore mansion. The stone walls muffled most sounds, but the wooden floorboards above her head allowed certain noises to penetrate. When she pressed her ear to the wall in just the right spot, she could hear voices from the rooms above.

At first, the sounds were just meaningless vibrations. But over time, as her other senses sharpened in compensation for the darkness, she began to distinguish words, then sentences, then entire conversations. She heard everything that happened in the Witmore household. She heard the colonel arguing with his business partners about debts and declining cotton prices.

She heard Helena berating the house slaves for imagined failures. She heard the three Witmore sons discussing their plans and their secrets when they thought no one was listening. She heard visitors arrive and depart. She heard whispered confessions and shouted accusations. The house above her held no secrets that she did not eventually discover, and she remembered everything.

By her second year in the cellar, Saraphina had developed a mental catalog of the Witmore family’s most closely guarded information. She knew that the colonel had borrowed heavily from a bank in New Orleans to cover gambling debts that he hid from his wife. She knew that the eldest son, William, had fathered a child with a free black woman in Vixsburg and was paying her to keep quiet.

She knew that the middle son, Robert, had stolen silver from the family collection and sold it to fund his drinking habit. She knew that the youngest son, Thomas Jr., was terrified of his mother and often cried himself to sleep at night. She also knew things about Helena. She knew that the mistress had once pushed ahouse slave down the stairs, causing the woman to lose her unborn baby and had convinced everyone it was an accident.

She knew that Helena docked the household accounts, skimming money into a private fund that she kept hidden from her husband. She knew that Helena had forged a letter to destroy her own sister’s engagement. 20 years earlier, a secret she had never told anyone. This knowledge became Saraphina’s most precious possession.

In the darkness, where she had nothing else, she had power. Not the power to escape, not yet, but the power of knowing, the power of waiting, the power of understanding her enemies better than they understood themselves. The years passed with agonizing slowness. Saraphina grew from a child into a young woman entirely within the confines of that cellar.

Her body adapted to the limited space as best it could. The chain around her ankle left a permanent scar, a ring of thickened skin that would mark her for the rest of her life. Her muscles weakened from lack of movement. Her skin, once a healthy brown, grew ashen from never seeing sunlight.

Her eyes, those remarkable amber eyes, developed the ability to see in almost total darkness, like a creature that had evolved for a life underground. But her mind grew stronger. Without external stimulation, she turned inward, developing a memory so precise that she could recall conversations she had overheard years earlier.

Word for word, she taught herself to think in organized patterns, to analyze information, to make connections between disperate pieces of knowledge. She played mental chess against herself, developing strategies and counter strategies that grew increasingly complex over time. She had no way of knowing it, but she was training herself to become something that the Witmore family could never have imagined. She was becoming dangerous.

Her mother, Ruth, tried to reach her. For the first 3 years of Saraphina’s imprisonment, Ruth managed to bribe one of the kitchen slaves to pass messages through the food deliveries. These messages were simple, just a few whispered words that the slave would repeat before leaving the cellar. Your mama loves you. Stay strong.

I’m still here. These fragments of connection were the only thing that kept Saraphina from losing hope entirely. But in the winter of 1862, the messages stopped. Saraphina waited for weeks, then months, listening for any word from her mother. Finally, she heard the truth from a conversation between Helena and the housekeeper.

Ruth had died. pneumonia. They said she had worked through a fever, too afraid of punishment to rest, and her lungs had filled with fluid. She was buried in the slave cemetery behind the cotton fields in an unmarked grave. Saraphina did not cry when she learned her mother was dead.

She had exhausted her tears years earlier. Instead, she felt something new crystallizing inside her. It was cold and hard and patient like a diamond forming under impossible pressure. It was hatred, not the hot, explosive anger that burns itself out quickly. This was something else entirely. This was the kind of hatred that could wait, that could plan, that could endure anything for as long as it took to achieve its purpose.

And now she knew exactly what that purpose would be. The war had already begun. Saraphina had listened to endless conversations about it through the floorboards above her head. In April of 1861, Confederate forces had fired on Fort Sumpter in Charleston Harbor, and the South had erupted in celebration. The Whitmore household was caught up in the patriotic fervor.

The colonel gave speeches about states rights and southern honor. The three sons argued about who would be first to enlist. Helena organized sewing circles to make uniforms for the local regiment. None of them understood what was coming. They believed their own propaganda, convinced that the war would be short and glorious, that the Yankees would be defeated within months.

Saraphina, listening from her cellar prison, knew better. She had heard the colonel’s private conversations with business associates who were less optimistic. She had heard the whispered concerns about British neutrality, about the Union naval blockade, about the difficulty of winning a war of attrition against a more industrialized enemy.

By 1862, the reality of war was beginning to penetrate even the isolation of the Whitmore plantation. Cotton prices collapsed as the blockade prevented exports to European markets. The oldest son, William, came home from Tennessee with a bullet wound in his shoulder and stories of carnage that silenced the dinner table. Supplies grew scarce.

The overseers were drafted into the Confederate army, replaced by older men and boys who could not maintain the same level of control. The enslaved population grew restless, sensing that something was changing, that the world they had known was beginning to crack. And in her cellar prison, Saraphina waited.

She had been in the darkness for5 years now, and she had learned the most important lesson that the darkness could teach. She had learned that patience was power. She had learned that silence was strength. She had learned that the things people tried to bury had a way of rising up again. She was 17 years old. She had not seen sunlight since she was seven.

She had not heard a kind word since her mother died. She had no reason to believe that her situation would ever change. But she knew with a certainty that went beyond logic or evidence that her time would come. The house above her was beginning to crumble. She could hear it in every worried conversation, every angry argument, every desperate prayer.

The Witmore family was running out of money, running out of allies, running out of time. The world that had created their wealth and power was collapsing, and they were too blind to see it. But Saraphina saw in the darkness where they had thrown her, she saw everything, and she was ready. The spring of 1864 brought changes that Saraphina could track through the sounds above her head.

The conversations grew more desperate. She heard Helena arguing with the colonel about selling off parcels of land to cover their debts. She heard William, now recovered from his wound, but permanently weakened, discussing the possibility of defeat with his brothers. She heard the house servants moving with less caution, speaking more freely when they thought the family couldn’t hear.

The balance of power was shifting, and everyone could feel it. The food deliveries became less regular. Sometimes an entire day would pass without anyone bringing Saraphina anything to eat. She learned to stretch her meager rations to ignore the constant gnaw of hunger that had become her permanent companion.

Her body had adapted to near starvation, becoming thin and wiry, requiring less sustenance to survive. This was not strength. This was simple biological desperation. But it meant that when others might have died, she endured. In November of 1864, she heard through the floorboards about something called Sherman’s march.

A Union general named William Sherman was cutting a path of destruction through Georgia, burning everything in his wake as his army moved from Atlanta toward the sea. The terror in Helena’s voice when she discussed this news with her husband was unmistakable. If Sherman turned north into Mississippi, if the Union Army reached Warren County, everything they had built would be destroyed.

Saraphina listened to their fear, and for the first time in 7 years, she smiled. The winter of 1864-65 was the hardest the Witmore plantation had ever experienced. The Confederate economy was in complete collapse. The paper money the family had accumulated was nearly worthless. Most of their slaves had run away, heading north toward the Union lines or simply disappearing into the chaos of a disintegrating society.

The overseers had long since abandoned their posts. The fields layow, the cotton rotting where it stood because there was no one left to pick it. Helena reduced the household staff to a skeleton crew of three enslaved people who had nowhere else to go. She dismissed the cook and took over the kitchen herself, something she had never done in her entire privileged life. The meals grew simpler.

The wine celler was emptied and sold. The silver was porned piece by piece to pay for basic necessities. The great house, once a symbol of wealth and power, began to show signs of neglect. Paint peeled from the columns. Shutters hung at crooked angles. The gardens grew wild with weeds. Through all of this, Saraphina remained in her cellar prison.

Helena seemed to have forgotten about her entirely, too consumed with the disaster unfolding above ground to think about the girl she had buried alive years earlier. The food deliveries became even more sporadic. Sometimes 3 or 4 days would pass without anyone opening the cellar door. Saraphina survived on rainwater that seeped through the tiny window and on rats that she caught with her bare hands in the darkness.

She had become something less than human and more than human at the same time. Stripped down to pure will and burning purpose. On April 9th, 1865, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulissiz S. Grant at Appamatics Courthouse in Virginia. The war was over. The Confederacy was dead. And somewhere in the darkness beneath the Witmore mansion, a young woman who had been imprisoned for nearly 6 years heard the news through the floorboards and knew that her moment was finally approaching.

The weeks following the Confederate surrender brought chaos to Warren County, Mississippi. Union troops began moving through the region, enforcing the terms of defeat and spreading word of emancipation to enslaved people who had not yet heard. Plantation owners who had ruled like kings now faced the collapse of everything they had known. Some fled.

Some took their own lives rather than accept the new reality.Others, like the Witmore family, simply refused to believe that their world had truly ended. Helena Whitmore continued to run her household as if nothing had changed. She gave orders to the remaining servants with the same imperious tone she had always used.

She spoke of the situation as temporary, a setback that would soon be corrected when proper order was restored. Her denial was so complete that it bordered on madness. The colonel, broken by the loss of everything he had worked for, retreated to his study and drank himself into a stouper every day.

The three sons scattered. William went to Vixsburg to see what could be salvaged of the family’s business interests. Robert disappeared entirely, running from gambling debts that had accumulated during the war. Thomas Jr., the youngest remained at the plantation, too afraid to leave and too weak to be of any use. And in the cellar, Saraphina waited.

She had waited for nearly 6 years. She could wait a little longer. The moment came on a warm evening in late May. Saraphina had been listening to the sounds above her head, tracking the movements of the remaining household members, as she had done for years. She heard Helena retire to her bedroom.

She heard the colonel’s drunken snoring from his study. She heard Thomas Jr. pacing in his room as he did every night, too anxious to sleep. And then she heard something she had never heard before. She heard the cellar door open at an unusual hour. A figure descended the stairs carrying a candle. The light, dim as it was, seemed blindingly bright to Saraphina’s darkness adapted eyes.

She shrank back against the wall, shielding her face with her hands. For a moment, she thought Helena had finally come to kill her, to eliminate the evidence of her crime before the Union authorities could discover it. But the voice that spoke was not Helena’s. It belonged to an old woman named Bessie, the same kitchen slave who had warned Ruth about Saraphina’s dangerous beauty all those years ago.

Bessie was 73 years old now, one of the few enslaved people who had remained on the plantation because she was too old and weak to run. But she had never forgotten the girl in the cellar. And now, with the old order crumbling around them, she had decided to act. Girl, Bessie whispered, her voice cracking with age and emotion. The war is over. You are free.

Do you understand me? You are free. Saraphina lowered her hands slowly, squinting against the candle light. She had not seen another human face in nearly 6 years. She had almost forgotten what people looked like. Bessie’s weathered features illuminated by the flickering flame seemed like something from a dream. Bessie had brought tools, a hammer, a chisel.

She had stolen them from the tool shed days earlier, hiding them under her mattress until the right moment. Now she knelt beside Saraphina and began working on the iron ring that had held the chain in place for so long. The metal was rusted, weakened by years of moisture seeping through the cellar walls.

It took nearly an hour of patient work, but finally the ring broke free from the stone. Saraphina stood for the first time in years. Her legs could barely support her weight. Her muscles had atrophied from disuse, leaving her as weak as a newborn. She leaned against the wall, breathing heavily, feeling the strange sensation of standing upright after so long, spent crouching and lying on the cold floor.

Bessie helped her up the stairs, one agonizing step at a time. The cellar door opened onto a hallway at the back of the house near the kitchen. The hallway was dark, but compared to the absolute blackness of the cellar, it seemed flooded with light. Zeraphina blinked, tears streaming from her eyes as they struggled to adjust.

“You need to go,” Bessie said. “You need to get away from this place before they find you gone. There are Union soldiers in Vixsburg. They will help you.” But Saraphina did not move toward the door. Instead, she turned and looked back into the house toward the main rooms where the Witmore family slept.

Her face, gaunt and pale from years of darkness, showed no expression. But her amber eyes, still remarkable despite everything she had endured, burned with a light that made old Bessie take a step backward. “No,” Saraphina said. Her voice was rusty from disuse, barely more than a whisper, but the word was clear. I am not leaving. Not yet. Bessie tried to argue.

She told Saraphina that staying was dangerous, that Helena would kill her if she found out she had escaped, that the only sensible thing to do was run and never look back. But Saraphina had not survived 6 years in that cellar by being sensible. She had survived by becoming something else entirely, something that did not run from its enemies, something that hunted them.

She told Bessie to go back to her cabin and pretend nothing had happened. She told her to act normal in the morning, to go about her duties as usual. Whatever happens, Saraphinasaid, “You did not see me. You do not know anything. Do you understand?” Bessie understood. She had lived her entire life under the rule of people who destroyed whatever they could not control.

She recognized that same quality in Saraphina’s eyes. Whatever the girl had become during those years in the darkness, she was not a victim anymore. She was something far more dangerous. That night, while the Witmore family slept, Saraphina explored the house she had only known through sounds and vibrations. She moved silently through the hallways, her bare feet making no noise on the wooden floors.

The layout was exactly as she had mapped it in her mind based on years of listening to footsteps and voices above her head. She knew which floorboards creaked. She knew which doors squeaked on their hinges. She knew where everyone slept and at what hours they typically woke.

She found Helena’s private office on the second floor, a small room where the mistress kept her personal papers and correspondence. The door was locked, but the lock was old and poorly maintained. Saraphina worked at it with a hairpin she had found on a dresser, using skills she had never been taught, but had somehow intuited during her years of isolation.

The lock clicked open within minutes. The office was exactly as she had imagined it. a small writing desk near the window, a cabinet against the wall, stacks of papers and ledgers organized with Helena’s characteristic precision. Saraphina moved through the room methodically, examining each document by the thin light of the moon coming through the window.

Her eyes, still more comfortable in darkness than in light, had no difficulty making out the words. She found everything she was looking for and more. She found the doctorred household accounts that proved Helena had been stealing from her husband for years. She found letters that documented the cover up of the slave woman’s death on the stairs.

She found correspondence with lawyers in New Orleans that revealed the full extent of the Witmore family’s debts, far worse than even the colonel knew. And she found something she had not expected. A letter from a doctor in Nachez dated 1858 confirming that Helena was barren and that the three sons she claimed to have born were actually purchased from a slave trader who dealt in light-skinned children who could pass for white.

This last discovery was staggering. The Witmore sons were not Whitors at all. They were the children of enslaved women, bought as infants and raised as white aristocrats. Helena had maintained this deception for over 30 years, terrified that the truth would destroy her social standing and her marriage.

It was the most closely guarded secret of her life. And now it belonged to Saraphina. She took the most important documents and hid them in a location outside the house that she had identified during her exploration. Then she returned to the cellar, closing the door behind her. When dawn came, she was back in her familiar darkness.

The chain arranged around her ankle to look as if it was still attached. No one would know she had ever left. For the next 2 weeks, Saraphina continued her nocturnal explorations. She grew stronger each day, forcing herself to exercise in the darkness, rebuilding muscles that had wasted away during her imprisonment.

She ate better now, taking food from the kitchen during her nighttime wanderings. The color began to return to her skin. Her movements became more fluid, more controlled. She was preparing herself for what was to come. During the days, she listened. She learned that William had returned from Vixsburg with terrible news. The family’s remaining assets had been seized by Union authorities.

The bank in New Orleans was demanding immediate repayment of the colonel’s gambling debts, threatening legal action if the money was not produced. Creditors were circling like vultures, sensing the weakness of a family that had once seemed invincible. Helena’s response to this crisis was to double down on her denial.

She insisted that they could rebuild, that the old ways would return, that they simply needed to hold on until proper order was restored. But her voice had taken on a desperate, brittle quality that Saraphina recognized. The mistress was losing control. The carefully constructed world she had built was falling apart around her, and she had no idea that the final blow was about to come from beneath her own feet.

Saraphina chose her moment carefully. On a Sunday morning in midJune, while the family was at breakfast, she emerged from the cellar for the last time. She had washed herself in the kitchen basin and dressed in clothes she had taken from a storage trunk. They were old and slightly too large, but they were clean.

She had brushed her hair and pinned it up in a simple style. For the first time in nearly 6 years, she looked almost human. She walked into the dining room without making a sound. The family was seated around the long mahogany table,picking at a meager breakfast of cornbread and weak coffee. Helena sat at one end, the colonel at the other.

Thomas Jr. sat between them, his eyes fixed on his plate. None of them noticed her at first. Then Helena looked up and screamed. The sound that came from the mistress’s throat was barely human. It was the scream of someone seeing a ghost, seeing the dead rise from the grave, seeing their worst nightmare made flesh.

She knocked over her chair as she stumbled backward, pressing herself against the wall, her eyes wide with terror. The colonel stared at Saraphina in confusion, not understanding what he was seeing. He had never known about the girl in the cellar. Helena had kept that secret from him as carefully as she had kept all her others.

To him, this was simply a strange young black woman who had somehow entered his home. His first instinct was to call for help, to summon someone to remove this intruder. But there was no one left to call. “Good morning,” Saraphina said. Her voice was calm and clear, stronger now than it had been when she first emerged from the darkness.

“I believe we have some matters to discuss.” Helena found her voice. “Get out,” she hissed. Get out of my house. I will have you whipped. I will have you killed. I will You will do nothing. Saraphina interrupted. Her tone was almost gentle. But there was steel beneath the softness. You will sit down and listen because I have things to tell your husband that he needs to hear.

The colonel looked between Saraphina and his wife, seeing the terror on Helena’s face and not understanding its source. What is the meaning of this? he demanded. Helena, who is this woman? That Saraphina said is an excellent question. Why don’t you tell him Mrs. Whitmore? Tell him where I have been for the past 6 years.

Tell him what you did to a 7-year-old child because you could not bear to look at her face. And she told him, she told him everything. She told him about the cellar, about the chain, about the years of darkness and isolation. She told him about the near starvation, the rats, the complete absence of human contact. She described it all in simple, precise language without emotion as if she were giving testimony in a court of law.

The colonel listened in growing horror. Whatever his faults, whatever his complicity in the system of slavery, he had never sanctioned anything like this. He had believed himself to be a gentleman, a man of honor. The idea that his wife had imprisoned a child in their cellar for years, had tortured her with isolation and neglect, was almost more than he could comprehend.

Helena tried to deny it. She called Saraphina a liar, a runaway, a thief who had broken into their home, but her denials were weak, contradicted by the obvious terror she had shown when Saraphina first appeared. And when Saraphina produced a handful of documents from inside her dress, Helena’s face went white. These are from your private office, Saraphina said, “The household accounts you have been doctoring for years.

The letters about the woman who fell down the stairs, and this one is particularly interesting.” She held up the letter from the doctor in Nachez. Helena lunged toward her, trying to snatch the paper from her hand, but Saraphina was faster. She stepped aside easily and Helena crashed into the dining table, sending dishes crashing to the floor.

“Your sons,” Saraphina said, addressing the colonel directly. “Now, they are not your sons. They are not your wife’s sons. They were purchased from a slave trader in 1829, 1831, and 1834. Light-skinned children. Who could pass for white? Your wife has been lying to you for over 30 years. The colonel stared at the letter in Saraphina’s hand. His face had gone gray.

He looked at Helena, who was sobbing now, collapsed against the table, her carefully constructed world finally crumbling around her. Thomas Jr. sat frozen in his chair, unable to process what he was hearing. Everything he had believed about himself, about his family, about his place in the world was being destroyed in the space of a few minutes. He was not a Witmore.

He was not white. He was the son of a slave purchased like property raised in a lie. The destruction of the Witmore family happened quickly after that morning. The colonel, confronted with the enormity of his wife’s deception, suffered a stroke within hours. He survived, but he was paralyzed on his left side and could no longer speak clearly.

He spent his remaining years in a wheelchair, cared for by servants who were now free and had to be paid wages the family could no longer afford. Helena was arrested 2 days later. Saraphina had sent copies of the most incriminating documents to the Union military commander in Vixsburg along with a detailed account of her imprisonment.

The occupation authorities were looking for ways to demonstrate their commitment to justice in the defeated south. Helena Witmore, a wealthy white woman who had imprisoned a child in a cellar for 6 years, was aperfect example. She was tried by a military tribunal and sentenced to 15 years in prison. She died of typhoid fever in her cell less than 2 years later.

The three Witmore sons scattered to the winds. William, the eldest, could not accept the truth about his origins. He put a pistol in his mouth 3 weeks after the revelation and pulled the trigger. Robert, the middle son, disappeared and was never heard from again. Some said he went west to California where no one knew his history.

Others said he drank himself to death in a New Orleans boarding house. Thomas Jr., the youngest, had a different reaction. He sought out Saraphina after everything had fallen apart and begged her for information about his real mother. She could not tell him much. The records were incomplete, the trail cold after so many years.

But she told him what she knew, and she watched something change in his eyes. He eventually moved north to Philadelphia, where he lived as a black man for the rest of his life, working as a teacher in a school for Freriedman’s children. The Witmore plantation was seized by the federal government and redistributed to formerly enslaved people under the provisions of General Sherman’s special field orders number 15.

The great white house, once a symbol of wealth and power, was divided into apartments for three black families. The cotton fields were parcled out into small farms. The world that James and Helena Whitmore had built was not just destroyed. It was transformed into something they would have found unimaginable. It became a community of free people living on land they owned, building lives that belonged to them.

And Saraphina walked away. She left Warren County in the summer of 1865 and headed north. She had no money, no possessions, no family left alive. But she had something more valuable. She had survived. She had triumphed. She had taken everything from the people who had tried to destroy her. And she had done it not with violence, but with truth.

The secrets they had tried so hard to keep had become the weapons of their destruction. She made her way to Memphis, then to St. Louis, then to Chicago. She worked as a domestic servant, as a seamstress, as a cook. She saved her money carefully, spending only what was necessary to survive. and she taught herself to read and write using newspapers and books she found discarded in the houses where she worked.

The same mind that had kept her sane in the darkness, that had memorized years of overheard conversations, had no difficulty mastering the written word. By 1870, Saraphina had saved enough money to open a small boarding house in Chicago’s growing black community. She ran it for 23 years, providing clean rooms and hot meals to black travelers who were turned away from white establishments.

She never married. She never had children. When people asked about her past, she said only that she had grown up in Mississippi and had left after the war. She did not speak about the cellar. She did not speak about the Wit Moors. That chapter of her life was closed. But she kept one thing from those years.

In a small wooden box that she hid under a floorboard in her bedroom, she kept the chain that had bound her ankle for nearly 6 years. The iron had rusted, the links had weakened, but it was still recognizable for what it was. Sometimes late at night, she would take it out and hold it in her hands, feeling its weight, remembering.

She did not keep it out of sentiment. She kept it as a reminder. A reminder of what human beings were capable of doing to each other. A reminder of what she had endured and overcome. A reminder that no matter how dark the darkness became, there was always a way back to the light. Saraphina Drake died in Chicago on February 14th, 1912.

She was 60 years old. The obituary in the Chicago Defender described her as a respected businesswoman and a pillar of her community. It mentioned her boarding house, her charitable work with newly arrived migrants from the south, her quiet dignity and strength. It did not mention Mississippi.

It did not mention the Witors. It did not mention the cellar. But there were those who knew. Old Bessie, who lived until 1889, told the story to her grandchildren before she died. Some of the formerly enslaved people who had worked on the Witmore plantation shared whispered accounts of the girl who had emerged from the darkness and destroyed her captives with nothing but the truth.

The story passed down through generations, changing and growing as oral histories do until it became more legend than fact. And perhaps that is fitting because the story of Saraphina Drake is not just the story of one woman. It is the story of everyone who has ever been buried alive by injustice and found a way to rise.

It is the story of the secrets that oppressors try to hide and the truth that always finds a way to surface. It is the story of a beauty that could not be destroyed, a spirit that could not be broken, and avengeance that was as patient as it was complete. Helena Whitmore tried to bury Saraphina in darkness because she could not bear to look at her.

She thought that by hiding the girl away, she could pretend she did not exist. She thought that chains and stone walls and years of isolation would destroy what she herself could never possess. She was wrong. The darkness did not destroy Saraphina. It forged her. It made her sharper, stronger, more patient than any enemy could imagine.

It taught her to listen when others spoke carelessly. It taught her to remember when others forgot. It taught her that the cruelty of the powerful is always built on secrets and that secrets are the most fragile foundations of all. In the end, Helena Whitmore was undone not by force, but by truth, not by violence, but by patience, not by hatred, but by the simple unstoppable power of a human being who refused to be erased.

She spent years trying to hide Saraphina from the world. But the world has a way of finding what is hidden. And sometimes what emerges from the darkness is more powerful than what put it there. This is the story of Saraphina Drake, the prisoner of beauty, the girl in the cellar, the woman who waited 10 years in darkness and emerged to bring light to those who had wronged her.

Her story was buried for over a century, lost in the vast ocean of suffering that was American slavery. But stories like hers have a way of surfacing. They rise through the cracks in history. They demand to be heard because the truth cannot be chained forever. And beauty, real beauty, the beauty of the human spirit can survive anything.

Even 6 years of darkness, even a lifetime of injustice, even the determined cruelty of those who fear what they cannot control. Saraphina Drake knew this. She learned it in the cellar beneath the Witmore mansion in the endless darkness where she should have been destroyed. She carried that knowledge with her for the rest of her life.

And now, more than a century after her death, her story carries it forward still. Some chains are made of iron, others are made of secrets and lies. Both can be broken, both will be broken. It is only a matter of time. And Saraphina had all the time in the world.